Louisville and Portland Canal

Coordinates: 38°16′18″N 85°46′46″W / 38.27170°N 85.77940°W

The Louisville and Portland Canal was a 2-mile (3.2 km) canal bypassing the Falls of the Ohio River at Louisville, Kentucky. The Falls form the only barrier to navigation between the origin of the Ohio at Pittsburgh and the port of New Orleans on the Gulf of Mexico; circumventing them was long a goal for Pennsylvanian and Cincinnatian merchants.[1] The canal opened in 1830 as the private Louisville and Portland Canal Company but was gradually bought out during the 19th century by the federal government, which had invested heavily in its construction, maintenance, and improvement. The Louisville and Portland Canal became the McAlpine Locks and Dam in 1962 after extensive modernization.[2]

The canal was the first major improvement to be completed on a major river of the United States.[3]

History

Background

The Falls of the Ohio are the only natural obstruction to riverine traffic from the source of the Ohio at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to the Gulf of Mexico. Some of the earliest cities in Kentucky – Louisville, Portland, and Shippingport – developed from the need for portage of cargo around the rapids, except during a few weeks each spring when water on the river was very high. Although this source of income was popular with locals, merchants invested upriver – particularly those in Pittsburgh and Cincinnati[1] – disliked the expense and hassle. The situation caused wide fluctuations in prices up- and downstream, as there was always a glut of shipments during the few weeks of high water each year.[4]

The first meeting of the trustees of the Town of Louisville on February 7, 1781, adopted a petition to the Virginia General Assembly for the right to construct a canal around the falls.[1] Two years later, engineer and canal advocate Christopher Colles petitioned the Congress of the Confederation, promising to start a canal company in exchange for a grant comprising the necessary land. They declined.[5]

Serious plans for a canal circulated throughout the early 1800s, with Cincinnatians in particular advocating a northern route through Indiana in order to blunt competition from Louisville. Canal companies were chartered by the state legislatures of both Kentucky and Indiana in 1805, but nothing came of either effort.[6] In 1808, the Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin suggested national funding for a Kentucky-side canal. The United States Senate passed bills to this effect in 1810 and 1811, but both died from Democratic opposition in the House.[7] Gen. William Lytle II, founder of Cincinnati, laid out Portland in 1811 and sold lots in order to finance his own canal project. The Indiana Canal Company, that state's second effort, was chartered in 1818 and made preliminary excavations using private and state funds. The failure of a dam and the Panic of 1819 ended the attempt.[6] Rumors that the Indianan dam had been sabotaged arose from the risk a canal posed to much of Louisville's economy, including not only forwarding, storage, drayage, and shipping but also provisioning, financing, hotels, and entertainment. Against this, however, some locals argued for the benefit a canal would provide to local manufacturing.[1]

Privately held company

Despite the completion of the federally funded National Road in the 1810s and the state-funded Erie Canal in the 1820s (the latter of which cut transportation costs across New York by around 95%), continuing Democratic and Louisvillian opposition crippled attempts to fund a public canal in the Kentucky General Assembly. Instead, Charles Thurston of Louisville sponsored a bill to charter the private Louisville and Portland Canal Company. The charter established an initial toll of 20¢ per ton, permitted the company to operate the canal in perpetuity, and granted it powers of eminent domain over land necessary to the canal's construction. The initial estimates in 1824 called for one year of construction at a cost of $300,000.[8]

The company was chartered in 1825. Its initial members included James Guthrie, John J. Jacob, Nicholas Berthoud, John Colmesnil, James Hughes, Robert Breckinridge, Isaac Thom, Simeon Goodwin, Charles Thurston, Worden Pope, William Vernon, Samuel Churchill, James Brown, and James Overstreet. Guthrie was elected president.[9] The canal was authorized by its charter to sell up to 6000 shares of stock at a cost of $100 each, but the company required only $10 down and an additional $10 quarterly.[9] In this way, $350,000 was raised from the initial sale of stock in March 1826, and $150,000 soon after. Much of this capital came from Philadelphia investors.[1] This private, out-of-state ownership was praised at the time by Louisville's leading newspaper, the Public Advertiser, which said "no one is now apprehensive of any imprudent or unjust action on the part of the Legislature". In May 1826, the United States Congress voted to purchase 1,000 shares as well.[8]

Construction began in 1826. As it became evident that the canal would have to be dug through solid rock, the cost estimate rose past $375,000, with two years of construction required. Local investors were the first to learn of the difficulties; several defaulted on further payment towards their shares, reducing the company's available capital. Abraham Lincoln is said to have worked on the construction of the canal in 1827.[10] The course was found to require adjustment, and Congress invested an additional $133,500 in 1829.[8] The company was still due to run out of funds by the end of 1829, and a third influx of funds from Congress was vetoed by the newly elected Pres. Andrew Jackson, who denounced the practice of giving federal funds to private corporations. The company was forced to borrow $154,000 in 1830. By this time, the stock was valued at over $1,000,000, of which the federal government held $290,000.[8]

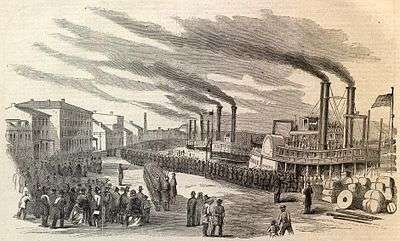

The first ship – the SS Uncas – passed through the partially completed locks in December 1830. The canal was fully completed in 1833, six years behind schedule. Its 50-foot (15 m) wide dimensions were huge in comparison with projects like the Erie Canal and intended to permit full-sized ships to pass from one side of the falls to the other. Nevertheless, the growing power and size of steamboats left the canal nearly obsolete soon after opening at the same time that the Alabama Fever and booming Black Belt cotton plantations increased demand for produce and goods from the north.[1] The canal increased its prices to 40¢ per ton in 1834 and to 60¢ per ton in 1837 and still saw traffic increase from 170,000 tons in 1834 to 300,000 in 1839.[8] At the same time, Louisville's "carrying trade" also increased to a greater volume than before[1] and a line of the Lexington and Ohio Railroad was constructed beside the canal from Louisville to Portland in 1838.

The company's high tolls and disinterest in improving the canal either to enlarge it or to correct the lower end, which opened into a narrow part of the river with a swift current, provoked dissatisfaction among its customers. Ohioan and Pennsylvanian opposition in Congress sometimes passed bills in the Senate approving a full buyout of the company, but such bills were consistently defeated in the House by Kentuckians, Southern proponents of states' rights such as Rep. Jefferson Davis (D–MS), and Indianan representatives, who still hoped to build their own canal as late as 1842.[11] The company's management opted to solve the problem on their own: instead of funding expansions, improvements, or dividends, profits from the canal were used to purchase privately held shares at a premium, gradually increasing the government's ownership stake. Despite the succession of long depressions set off in 1837 and 1843 and a reduction of the toll to 50¢ per ton in 1842, the company remained highly profitable, and the buyout was completed in 1855.[11]

Government-acquired corporation

By the 1850s, around 40% of the steamboats on the Ohio were too large for the canal and required transshipment of their cargo around the Falls.[1] Despite holding full ownership of the company after 1855, the federal government found it impossible to get Congress to approve taking formal control of the canal. Bills offered from 1854 to 1860 failed on grounds of constitutionality, economy, and efficiency. Sen. Lazarus Powell (D-KY) was of the opinion that "the only reason why the government of the United States has not long taken charge of the canal, is the fear that there would be demand on the national treasury to Enlarge it", a reasonable fear given the reasons for the buyout of the original owners.[12]

In the end, the government simply directed the company to finance the needful improvements on its own. A $865,000 plan was approved and undertaken in 1860 but was almost immediately shelved by the Civil War. The facility was a target of Confederate forces in Kentucky, at least one of whom advocated destroying it so "future travelers would hardly know where it was",[14] but Union control of the state rendered the threat moot. The loans involved in the original plan, however, meant that the company was $1.6 million in debt by 1866.

Radical Republican control of Congress meant that the Army Corps of Engineers was finally allowed to take over improvements for the canal in 1867. Two new locks, each 390 feet (120 m) long and 90 feet (27 m) wide, opened in February 1872.

Government control

In May 1874, Congress passed a bill allowing the Corps of Engineers to take full control of the canal and authorizing the Treasury to pay off the bonds for the recent improvements. By 1877, despite the vastly increased use of railroads, traffic on the canal had tripled from any previous level.[15] This was mostly heavy, low-value industrial supplies such as coal, salt, and iron ore. In 1880, under political pressure from upriver producers, Congress removed the canal's tolls entirely, forgoing profit and paying the entirety of its expenses from the Treasury.[16]

A new lock was built in 1921 as a part of Congress's plan for the "canalization" of the Ohio River. Further expansions in 1962, increasing the width of the canal to 500 feet (150 m), caused the canal to be known as the McAlpine Locks and Dam.[17]

Economic impact

In the 19th century, the high toll and insufficient capacity of the canal served Louisville well, permitting high profits for shareholders without greatly curtailing the portage and related sectors of the local economy. The gradual buyout well-compensated the owners for their initial investments in the venture.

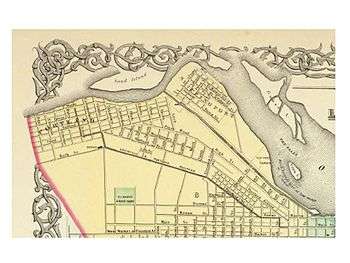

Louisville boomed at the expense of its onetime partners Portland and Shippingport, which were relegated to backwater status. Portland, after initially continuing to grow and incorporating separately in 1834, accepted a proposal to widen the canal and annexation to west Louisville in 1837 in exchange for its wharf becoming the terminus of the Lexington and Ohio Railroad; when the western line of the railroad only managed to successfully connect Portland with Louisville before its 1840 bankruptcy, the community removed itself again from 1842 to 1852, before accepting reannexation. Much of the community was destroyed by or razed after the floods of 1937 and 1945. Shippingport, included within Louisville's borders during its 1828 incorporation and enisled by the canal, declined slowly until the government bought out the remaining families in 1958.[18]

At the same time, these factors blunted the economic impact of the canal on other communities up- and downstream. Although (even at its highest tolls) the canal decreased the freight rate along the river, it did not permit significantly lower prices in commodities, which fell at a faster rate in the 25 years before the canal opened than they did in the 25 years afterwards.[3] The 1850s and 1860s particularly saw usage of the canal merely plateau despite booming growth in river traffic.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Yater, George. The Encyclopedia of Louisville, p. 531. "Louisville and Portland Canal". University Press of Kentucky (Lexington), 2001. Accessed 9 October 2013.

- ↑ Trescott, Paul B. (March 1958). "The Louisville and Portland Canal Company, 1825-1874". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. Organization of American Historians. 44 (4): 686–708. doi:10.2307/1886603. JSTOR 1886603..

- 1 2 Trescott, 694.

- ↑ Trescott, 686-687.

- ↑ Hulbert, Archer Butler, ed. (1918). "XVIII Colles' Petition to Improve Ohio River Navigation (1783)". Ohio in the Time of the Confederation. Marietta College Historical Collections. 3. Marietta, Ohio: Marietta Historical Commission. pp. 92–94..

- 1 2 Trescott, 687.

- ↑ Trescott, 687-688.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Trescott, 688 ff.

- 1 2 Johnson, Leland & al.Triumph at the Falls: The Louisville and Portland Canal, pp. 30 ff. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Louisville), 2007.

- ↑ The Real Lincoln: a Portrait. Houghton Mifflin. 1922. Retrieved 30 July 2010..

- 1 2 Trescott, 695 ff.

- ↑ Trescott, 700-701.

- ↑ "History of the Kentucky & Indiana Terminal Railroad". Retrieved 24 May 2007..

- ↑ United States Army Corps of Engineers. Civil War Engineering and Navigation.

- ↑ Trescott, 702-706.

- ↑ Trescott, 706 f.

- ↑ The Falls City Engineers: A History of the Louisville District. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 1975..

- ↑ Burnett, Robert A. (April 1976). "Louisville's French Past". Filson Club History Quarterly: 9–18..