Multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle

A multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) is a ballistic missile payload containing several warheads, each capable of being aimed to hit one of a group of targets. By contrast a unitary warhead is a single warhead on a single missile. An intermediate case is the multiple reentry vehicle (MRV) missile which carries several warheads which are dispersed but not individually aimed. Only the United States, United Kingdom (Partner in development), Israel, Russia, France, India and China are known to have developed MIRV missiles.

Purpose

The military purpose of a MIRV is fourfold:

- Enhance first-strike proficiency for strategic forces.[2]

- Providing greater target damage for a given thermonuclear weapon payload. Several small warheads cause much more target damage area than a single warhead alone. This in turn reduces the number of missiles and launch facilities required for a given destruction level - much the same as the purpose of a cluster munition.[3]

- With single warhead missiles, one missile must be launched for each target. By contrast with a MIRV warhead, the post-boost (or bus) stage can dispense the warheads against multiple targets across a broad area.

- Reduces the effectiveness of an anti-ballistic missile system that relies on intercepting individual warheads.[4] While a MIRV attacking missile can have multiple warheads (3–12 on United States and Russian missiles), interceptors may have only one warhead per missile. Thus, in both a military and an economic sense, MIRVs render ABM systems less effective, as the costs of maintaining a workable defense against MIRVs would greatly increase, requiring multiple defensive missiles for each offensive one. Decoy reentry vehicles can be used alongside actual warheads to minimize the chances of the actual warheads being intercepted before they reach their targets. A system that destroys the missile earlier in its trajectory (before MIRV separation) is not affected by this but is more difficult, and thus more expensive to implement.

MIRV land-based ICBMs were considered destabilizing because they tended to put a premium on striking first. The world's first MIRV—US Minuteman III missile of 1970—threatened to rapidly increase the US's deployable nuclear arsenal and thus the possibility that it would have enough bombs to destroy virtually all of the Soviet Union's nuclear weapons and negate any significant retaliation. Later on the US feared the Soviet's MIRVs because Soviet missiles had a greater throw-weight and could thus put more warheads on each missile than the US could. For example, the US MIRVs might have increased their warhead per missile count by a factor of 6 while the Soviets increased theirs by a factor of 10. Furthermore, the US had a much smaller proportion of its nuclear arsenal in ICBMs than the Soviets. Bombers could not be outfitted with MIRVs so their capacity would not be multiplied. Thus the US did not seem to have as much potential for MIRV usage as the Soviets. However, the US had a larger number of Submarine-launched ballistic missiles, which could be outfitted with MIRVs, and helped offset the ICBM disadvantage. It is because of this that this type of weapon was banned under the START II agreement. However, START II was never ratified by the Russian Duma due to disagreements about the ABM treaty.

Mode of operation

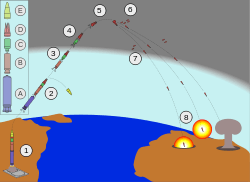

In a MIRV, the main rocket motor (or booster) pushes a "bus" (see illustration) into a free-flight suborbital ballistic flight path. After the boost phase the bus maneuvers using small on-board rocket motors and a computerised inertial guidance system. It takes up a ballistic trajectory that will deliver a reentry vehicle containing a warhead to a target, and then releases a warhead on that trajectory. It then maneuvers to a different trajectory, releasing another warhead, and repeats the process for all warheads.

The precise technical details are closely guarded military secrets, to hinder any development of enemy counter-measures. The bus' on-board propellant limits the distances between targets of individual warheads to perhaps a few hundred kilometers.[5] Some warheads may use small hypersonic airfoils during the descent to gain additional cross-range distance. Additionally, some buses (e.g. the British Chevaline system) can release decoys to confuse interception devices and radars, such as aluminized balloons or electronic noisemakers.

Accuracy is crucial, because doubling the accuracy decreases the needed warhead energy by a factor of four for radiation damage and by a factor of eight for blast damage. Navigation system accuracy and the available geophysical information limits the warhead target accuracy. Some writers believe that government-supported geophysical mapping initiatives and ocean satellite altitude systems such as Seasat may have a covert purpose to map mass concentrations and determine local gravity anomalies, in order to improve accuracies of ballistic missiles. Accuracy is expressed as circular error probable (CEP). This is simply the radius of the circle that the warhead has a 50 percent chance of falling into when aimed at the center. CEP is about 90–100 m for the Trident II and Peacekeeper missiles.[6]

MRV

A multiple reentry vehicle payload for a ballistic missile deploys multiple warheads in a pattern against a single target (as opposed to multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle, which deploys multiple warheads against multiple targets). The advantage of an MRV over a single warhead is that the damage produced in the center of the pattern is far greater than the damage possible from any single warhead in the MRV cluster, this makes for an efficient area attack weapon. The number of warheads makes interception by anti-ballistic missiles unlikely.

Improved warhead designs allow smaller warheads for a given yield, while better electronics and guidance systems allowed greater accuracy. As a result, MIRV technology has proven more attractive than MRV for advanced nations. Because of the larger amount of nuclear material consumed by MRVs and MIRVs, single warhead missiles are more attractive for nations with less advanced technology. The United States deployed an MRV payload on the Polaris A-3. The Soviet Union deployed MRVs on the R-36 Mod 4 ICBM. Refer to atmospheric reentry for more details.

MIRV-capable missiles

- RS-28 Sarmat

- R-36M2 (SS-18)

- RSM-54 R-29RMU2 "Layner"

- RSM-56 R-30 "Bulava"

- RS-26 Rubezh

- RS-24 Yars

- UR-100N (SS-19)

- RT-2UTTH "Topol M" (SS-27)

- RSM-54 R-29RMU "Sineva"

- Jericho 3

- DF-5B

- DF-31A, DF-31B

- DF-41

- M51 (missile)

- M45 (missile)

- Minuteman III

- UGM-133 Trident II (D5LE)

- JL-2

See also

|

|

References

- Notes

- ↑ Parsch, Andreas. "UGM-133". Directory of U.S. Military Rockets and Missiles. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

- ↑ "Multiple Independently Targetable Reentry Vehicles (MIRVs)". Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ↑ The best overall printed sources on nuclear weapons design are: Hansen, Chuck. U.S. Nuclear Weapons: The Secret History. San Antonio, TX: Aerofax, 1988; and the more-updated Hansen, Chuck, "Swords of Armageddon: U.S. Nuclear Weapons Development since 1945" (CD-ROM & download available). PDF. 2,600 pages, Sunnyvale, California, Chukelea Publications, 1995, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9791915-0-3 (2nd Ed.)

- ↑ Robert C. Aldridge (1983). First Strike!: The Pentagon's Strategy for Nuclear War. South End Press. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-0-89608-154-3. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ Question Re Mirv Warheads — Military Forum | Airliners.net

- ↑ Cimbala, Stephen J. (2010). Military Persuasion: Deterrence and Provocation in Crisis and War. Penn State Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-271-04126-1. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to MIRV. |

- "MIRV: A BRIEF HISTORY OF MINUTEMAN and MULTIPLE REENTRY VEHICLES" by Daniel Buchonnet, Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, February 1976.

- Operation 1964

- The Defense of the United States, 1981 CBS Five-Part TV Series from Google Video