Manchán of Mohill

| Saint Manchan | |

|---|---|

Saint Manchán, of Mohill | |

| Missionary, Monk | |

| Born |

Before AD 500 Ireland or Wales |

| Died |

c. AD 535-538 probably Mohill, Ireland |

| Venerated in | |

| Feast | 25 February (14 February in Julian calendar) |

| Patronage |

St. Manchan's school, Monaghan day, Mohill, co. Leitrim monastery of Mohill * monastery of Inisnag * other churches * invoked against plague (* destroyed, or ruins) |

| Controversy | Multiplicity of Manchans, Shrine of Manchan, Churches, Nationality |

Saint Manchan (Irish: Manchán, midEng: Mancheanus, Managhan,[1] Monahan[2]) of Mohill (Irish: Maethail, Maothail, midEng: Moithla, Latin: Nouella), died AD 535-538, was an early Irish Christian saint, credited with founding multiple churches.

The life of Manchan of Mohill is obscured because many persons named Manchan are to be found among the monastically-inclined Medieval Irish Christians, not least because the names are a diminutive of Irish: Manach Latin: Monachus, a monk.[3] Manchan probably died of famine, as volcanic winters of 535-536 devastated agriculture, and the subsequent Late Antique Little Ice Age brought plague to Europe.

The Shrine of Manchan is a remarkable and unique example of Irish Urnes style art, adapted to Ringerike style, skillful in design and execution.[4] Saint Manchan's feast day is celebrated February 25 (Feb 14 in the Old Calendar), by Roman Catholics, and Anglicans.[5]

Life

Little of certainty is known about the life of Manchán of Mohill. The Book of Fenagh states Manchan was contemporary with Saint Caillín (fl. AD 464),[6] and his in-commendam successor as Abbot of Fenagh Abbey,[7] suggesting Manchan flourished c. 464-538. Though his genealogy has been widely debated, Cronnelly gives the following objectionable pedigree for "St. Manchan of Mohill"-

- Manchan mac Siollan mac Conal mac Luchain mac Conal Anglonaig mac Feice mac Rosa mac Fachta mac Seanchada mac Aille Ceasdaig mac Rory (King of Ireland).[8][9]

Asserting a 7th century Saint, various sources, including the Lost biography of Manchan, claim Manchan died c. AD 652,[10][11][12] on the assumption Manchan of Mohill and Manchán of Min Droichit are identical,[10][13][14] but others sources dispute the claim.[5][15] and their feast days disagree in Julian calendar and Gregorian calendars. Conversely, Manchan of Mohill and Manchan of Lemanaghan (died A.D. 664) may be identical,[1][8][16][17][18] despite feast dates and centuries disagreeing,[10] and an apparent multiplicity of "Manchán's of Lemanaghan" complicating matters further.[19][n 1] "Colgan says that, for want of authentic documents to prove the contrary, he must consider them as different persons".[22]

There is reason to speculate Saint Manchan of Mohill is connected to Wales. In the National Library of Wales, a manuscript records several Meugan festivals, including February 14, the festival of Manchan, abbot of Mohill, co. Leitrim.[23] This welsh Meugan may have been the Moucan, or Maucan, mentioned in the Life of St. Cadoc the Wise, who lived at the monastery of Llancarfan in Glamorganshire.[24][25] While Colgan conjectured Manchan of Mohill was contemporary with a Saint Menath (Monach? Monachus?), a disciple of Saint Patrick,[26] John O'Donovan said the translator of the Annals of Clonmacnoise had disbelievingly recorded "the Coworbes of Saint Manchan say that he was a Welshman, and came to this kingdom at one with Saint Patrick".[9]

Unfortunately, a multiplicity of Saints named "Irish: Manchán, Manachán, Mainchéin, Mainchin, Monahan Latin: Manchianus, Mancenus, Manichchaeus" is because the name is a diminutive of Irish: Manach Latin: Monachus, a monk,[27][28] so real names for each Mainchín are not known.[29]

Considering all pre-20th century historians appear unaware a 6th century death for Manchan of Maethaill is recorded by the Annals of Tigernach, the balance of evidence identifies Manchán of Mohill as a distinct personality,[10][30] flourishing in the 5th and 6th century.[31] Significantly, the Irish Annals identified him, uniquely among all Mainchín's, as the Saint whose relics are venerated by the "Shrine of Manchan of Maothaill",[32] perhaps jointly.[33]

Missionary work

Manchán of Mohill, uniquely among Mainchín's, is credited with founding up to four,[34][35] or seven[17][27][36][37][38] early Christian churches. The martologies of Irish Saints coin the expressions Latin: 'Manchani Maethla, cum sociis suis' "Manchán of Mohill and his companions" and Latin: 'cum sociis' "with allies", both allusions to "his other churches".[5][39] The locations of all Manchan's churches are not recorded, so must be inferred from available evidence.

Firstly, Manchan founded the early Christian monastery of Mohill, in county Leitrim, in the 6th century. The monastery site is presently occupied by a Protestant church, and only an old school house remains, though the original monastery was of considerable extent.[40][41]

Secondly, John O'Hanlon confirms "At Inisnag, diocese of Ossory, St. Manchan, whose feast occurs on the 14th of February, was venerated as a patron (Statuta Dioecesis Ossoriensis)",[40] suggesting the Monastery of Inisnag was founded by Manchan. From Inisnag, the townland of Irish: Cill Mhainchín ("Kilmanaheen" meaning church of Manchan) is found c. 10km east, and the townland of Irish: Cill Manchin ("Kilmanahan", church of Manchan) sits c. 40km south-west. This connection introduces the notion of a missionary monk.

Curiously, the Mohill-County Kilkenny route bisects both the communities of Lemanaghan and Mondrehid. John O'Donovan believed Manchan of Mohill founded the Lemanaghan church, in county Offaly- "Manchan was an intimate friend of St. Caillin, the Executor of his Will and his successor in the Abbacy of Fenagh. He was the son of Innaoi and his Festival was celebrated at Liath-Manchain on the 24th of January".[21] Giraudon (2010) makes a similar claim- "[from french]: Saint Manchàn would have lived in the sixth or seventh century of our era. He was born in Mohill, County Leitrim. For some, he would be the son of Daga, for the others, of Innaoi. His mother's name was Mella and he had two sisters, Grealla and Greillseach. He spent most of his life in Leamanachan".[18] These persistent claims Manchan of Mohill moved to Lemanaghan, county Offaly, might be true but Manchan of Lemanaghan must be a later successor - unless the Annals of Tigernach wrongly gave Manchan of Mohill a 6th century life, offering an implication Manchan of Mohill and Lemanaghan are indeed the same personality.

Strengthening his southern-Ireland association, the Book of Fenagh claims Manchan of Mohill accompanied the elderly Saint Caillin to Liath Mhór, County Tipperary.[42][43][n 2] Again, this Mohill-Liath Mhór route bisects the communities of Lemanaghan and Mondrehid. The association with Leigh, County Tipperary is curious. Leigh translates to Irish: Liath, and Lemanaghan translates to Irish: Liath-Mancháin, a contradiction of place and personal names. It follows that Manchan of Lemanaghan could mean "Manchan, from the place of Manchan from Liath", strong evidence for the earlier predecessor called "Manchan Leith Móir[n 3] named in the "old ancient vellum book",[45][46] clearly connecting some Saint Manchan with Liath Mhór, County Tipperary.

Travel

Overall, the well-defined Manchan north-south route, Mohill-Liathmore-Inisnag, clearly afforded a missionary Manchan opportunities to establish his various churches. He probably travelled via sea and inland-waterways when possible, because overland conditions were difficult, often dangerous, and long-distance travel by road was generally slow and uncomfortable". The key rivers serving the Manchan route was the River Shannon, the Rinn river in County Leitrim, the Munster River and Kings River serving Tipperary/Killkenny, and the River Nore serving County Waterford and south-east generally. The sea-route between County Wexford and Wales was also one of the most important travel routes in Europe.

Possible churches

Combining the various claims with circumstantial evidence, Manchan of Mohill may be associated with some of these early Christian churches in the 5th and 6th centuries-

- Inisnag (Irish: Inish Snaig), County Kilkenny:- Founded by Manchan in 5th-6th century. Patron Saint, according to O'Hanlon and Ossory diocesan records.

- Kilmanaheen (Irish: Cill Mhainchín), County Kilkenny:- "Kilmanaheen", a corruption of Irish: Cill Mhainchín meaning "Manchán's church", lies only 10 km from Inisnag. St. Natilis is an alternative 7th century founder.

- Leighmore (Irish: Liath Móir), County Tipperary:- Ó Donnabháin (and O'Rian, Book of Fenagh) connect Manchan of Mohill with Liath Móir, and the "Litany of Irish Saints" mentions "Manchan Leith Móir". St. Mochaemhog (died 646) is the alternative 7th century founder.

- Kilmanahan (Irish: Cill Mainchín), County Waterford:- "Kilmanahan" is a corruption of Irish: Cill Mhainchín, meaning "Manchán's church", and lies 40 km south of Inisnag and Liath Móir. Coummahon townland (Irish: Chom Machan tentatively meaning "Manchán's valley") is 20 km south-east.

- Mondrehid (Irish: Mion Droichid), County Laois:- O'Hanlon (and Lewis, Geoghegan, Ware, etc) associate Manchan of Mohill to this place. The Manchan route passes Irish: Mion Droichid en-route to both Liath and Inis Snaig. St. Laisren (died 600) is an alternative 6th century founder.

- Lemanaghan (Irish: Liath Mancháin), County Offaly:- O'Donovan (and Reynolds, Healy, Monaghan, Giraudon, etc) associate Manchan of Mohill and the "Shrine of Manchan of Moethail" to this place. Manchan of Lemanaghan is an alternative 7th century founder.

- Kilmanaghan (Irish: Cill Mhancháin, County Offaly:- Kilmanaghan townland and parish, lies on the Manchan route. Manchan of Lemanaghan is an alternative 7th century founder.

- Athleague (Irish: Áth Liag Maenaccáin), County Roscommon:- Via Connacht, the Manchan north-south route will pass Atha Liacc Maenaccain, "the place of Manchan of Liacc". The very obscure Maonacan is the alternative 6th century founder.

- Mohill (Irish: Maothail-Manchán), County Leitrim:- O'Hanlon (and Whelan, Ardagh diocesan records, etc) associate Manchan of Mohill and a "Shrine of Manchan of Maethail" to this place.

Famine and death

The Annals of Ulster, Annals of Tigernach and the Annals of the Four Masters have a cluster of deaths for person(s) named Mochta (died 535), Mocta/Mauchteus (d. 537), and Manchán (d. 538). These entries could correlate to the one person, but the entry for A.D.538 is unequivocal-

- "A.D. 534, Saint Mochta, Bishop of Lughmhagh, disciple of St. Patrick, resigned his spirit to heaven on the nineteenth day of August."[32]

- "A.D. 535, The falling alseep of Mochta, disciple of Patrick, on the 13th of the Kalends of September. Thus he himself wrote in his epistle: Mauchteus, a sinner, priest, disciple of St Patrick, sends greetings in the Lord’",[47] "A.D. 537, Or here, the falling asleep of St Mochta, disciple of Patrick".[47]

- "AD 538: Manchán of Maethail fell (Irish: Manchan Maethla cecídit)".[31]

Manchán probably died as a result of famines caused by the extreme weather events of 535-536. The Irish Annals cite the weather events, and resulting famine, as "the failure of bread" giving the years 536AD, 538AD, and 539AD.[31][48][49] Three immense volcanic eruptions occurred in 536, 540 and 547. The 6th century events probably had significant impact on Christianity across Ireland. In the eyes of the Christian and pagan Irish, the dramatic events perhaps illustrated the divinity and sanctity of Manchán. The remains of Manchan of Mohill were probably preserved for a long time in a Monastery, before being enshrined.[50][51]

Justinian plague of Mohill

Following the death of Manchán, the population of Mohill (barony), and the Airgíalla kingdom, were devastated by the Justinian plague, an early phenomena of the Late Antique Little Ice Age c. 536-660AD. Evidence for the Justinian plague is provided by three contiguous townlands, south-west of the present town, all anciently named after Irish: Tamlachta. Recognition the word tamlacht signifies a mass plague burial place is widespread, but most communities retain little knowledge of their own localities experience.[52] Confirmed Bubonic plague mass burial sites at Maothaill-Manchan are Tamlaght More, Tamlaght Beg, and Tamlaghtavally, forming a quadrant to the south-west of the town, centred on the monastery site.[53]

- "Tamlaghavally townland: Taibhleacht a' Bhaile or Taibhleacht an Bhealaigh, the plague burial ground of the town or roadway. Taibhleacht is derived from tamh or taimh, an unnatural death as from a plague, and leacht signifies a bed or grave. It was a place where people who died from a plague were buried, generally in a common grave. People who passed the way were accustomed to raise a 'cairn' of stones over the spot by placing single stones over the grave. Tamlaght Beg and Tamlagh More are of the same origin. Some great plague or pestilence has left its name on those three townlands. "[54]

A sudden climate change in the decade after 538 can be observed from dendrochonology studies of Irish trees, and the arrival of the Bubonic plague in Ireland c. A.D. 544, seems to correlate with the westward trajectory of the Justinianic plague, which had reached Gaul by A.D. 543.[55] Another epidemic in A.D. 550, christened the croin Chonaill (redness of C.), or the buidhe Chonaill (yellowness of C.), suggests a fairly widespread outbreak focused on the Shannon area.[56] In the northern half of Ireland, nearly all 41 Tamlachta sites are associated with water, though Mohill may be exception.[57][p 1]

The Four Masters state: "543AD, an extraordinary universal plague through the world, which swept away the noblest third part of the human race",[32] and the Annals of Ulster christened the pandemic "bléfed".[48] It is estimated 25–50 million, or 40% of European population, died over two centuries as the plague returned periodically until the 8th century.

- "The huge dying off in the 6th century. which is suggested by the number of tamlachta sites would certainly have created fear if not widespread panic. This was a pandemic in which some people dropped dead in less than one day, some fell ill but recovered, and some remained unaffected. Such seemingly random results might have been interpreted by the populace, even preached by the clerics, as evidenced of divine selection."[58]

Mohill was near the Airgíalla kingdom which was uniquely hard hit by pandemic.[59] There was a great surge in ringfort-building after the plague of 545 AD, as the populace on the boundary of devastated regions, Airgíalla and Mohill (barony), sought security from mysterious and widespread death, riving, cattle-raids, enslavement, and worse.[60] These forts (called Raths) were entrenchments the Irish built about their houses.[61]

Christian veneration of Manchán

Manchán of Mohill became a saint in Irish and Welsh tradition. His sanctity is recorded in the "Book of Caillin / Leabar Fidhnacha",[7] and the Annals of the Four Masters.[32] The "Martyrology of Donegal" records the Saint as "Latin: c. sexto decimo kal. martii. 14. Mainchein, of Moethail Latin: Cum sociis meaning "with Allies",[5] while "The martyrology of Gorman" notes "Manchéin of Moethail, Feb. 14. Latin: Manchani Maethla, cum sociis suis", meaning "Manchán of Mohill and his companions".[39] The "Mostyn Manuscript No. 88", in the National Library of Wales, records several Meugan festivals, including February 14, festival of Manchan, abbot of Mohill.[23] Circa AD 1753, the celebration of the feast day of Manchán of Mohill moved from February 14 in the Old Calendar to February 25, in the New Calendar.

Mohill-Manchan

The mid-6th century fear and panic from plague, experienced by populace of south county Leitrim, may have encouraged widespread conversion to Christianity, veneration of Manchán, and invigorated the monastery of Mohill. This conversion is reflected in the multitude of monasteries which sprang up at mid-century, across Ireland.[60] Manchán is venerated as patron Saint of Mohill-Manchan, and invoked for protection from Bubonic plague,[p 2] since this tumultuous time. The parish in Mohill (barony) is named Mohill-Manchan, and in the 19th century, John O'Donovan claimed "Monahan's (or St. Manchan's) Well is still shown there",[2] though it is unclear where in Mohill the holy well is located. From 1935 to 2015, the GAA football park in Mohill, which was officially opened to great fanfare on 8 May 1939, was named after Manchan,[63] and teams from this club continue to preserve his name. St Manchan's Primary School in Mohill was officially opened in 2010, at a cost of 2.6 million euro.[64]

Manchán's fair (Monaghan day)

Until the late 20th century, the renowned festival of Manchán, name corrupted to Monaghan day", was held in Mohill each year, on the feast day of the Saint,[2] or rather on the Twenty fifth of February.[65][66] The date of the ancient fair of Manchán moved to February 25, in the New Calendar, from February 14 in the Old Calendar, c. AD 1753. The plot of the aclaimed novel by John McGahern, titled "Amongst Women", revolves around "Monaghan day (Manchán's fair)" in Mohill, county Leitrim.

Shrine of Manchán

In the 12th century, "Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair commenced his reign, with a present of a gold shrine, superior to any yet seen in Ireland, for the relics of St. Manchan of Moethail".[67] This Annals of the Four Masters record the following-

- "AD 1166, The shrine of Manchan, of Maethail (Irish: Scrin-Manchain of Maethail), was covered by Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, and an embroidering of gold was carried over it by him, in as good a style as a relic was ever covered in Ireland",[32][68]

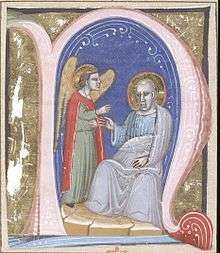

The loss of a distinct " shrine to Manchán of Mohill" is not recorded, so it must be the relic ascribed to Manchán of Lemanaghan[69] despite "Manchán of Maethail" named as being venerated.[10] This particular shrine is an impressive box of yew wood with gilted bronze and enamel fittings, a house-shaped shrine in the form of a gabled roof, originally covered with silver plates of which traces still remain. It stands 19 inches tall, covering a space dimensioned 24 x 16 inches, raised by short legs and clearing the ground surface by two and a half inches. The legs slot into metal shoes, attached to metal rings probably to be attached to carrying-poles when the shrine was leading a procession.[69] Animal patterns of beasts and serpent fill the bosses and borders of the shrine.[70] The animal ornament on the principal faces of the relic reveals influences of Irish Urnes style adapted to Ringerike style.[69][71]

The ten figures adorning the shrine are newer, probably 13th century.[69] It is believed the half-round cast-bronze figure carrying an axe on the Manchan Shine, is an early representation of Olaf II of Norway (Saint Olaf), considering the sub-viking context of the art, and iconographical association of a man with axe.[72] In 1861, a "appliqué" figure of gilt, cast copper-alloy, 13.7 cm high, 2.75 cm wide, and 1.7 cm thickness, was reportedly found in the grave-yard of Clonmacnoise, and presented with a short-beard and moustache, a pointed decorated hat covering his ears, hands flat on his bare-chest, with a pleated decorated kilt, one missing leg, and was very similar those remaining on the shrine of Manchan, so is assumed to have fallen off.[73] Margaret Stokes claimed a robed figurine holding a book, found buried near Saint John's Abbey at Thomas Street, Dublin, bears resemblance to the Manchan shrine figures, but "of much finer workmanship and evidently earlier date", but unfortunately she fails to expand further.[74]

The dress and personal adornment of lay and chieftain costume of the 13th century Irish is reflected by the figures.[75] The wearing of the "celt" (anglicized "kilt", pron. 'kelt'[76]), similar to the present-day Scottish highland kilt, was very common in Ireland, and all figures on the shrine of Manchán have highly long ornamented, emboidered, or pleated, "kilts"[73][77] reaching below their knees, as kilts were probably worn by both ecclesiastical and laypersons.[78] The wearing of full beards (Irish: grenn, feasog) was only acceptable for the higher classes (nobles, chiefs, warriors),[78] and it was disgraceful to present with hair and beard trimmed short. Reflecting this, all the shrine of Manchán figures have beards cut rectangularly, or Assyrian style, usually with no moustache.[78]

The technical and stylistic similarities to the "Cross of Cong group",[a 1] confirms without doubt the shrine of Manchan was crafted at the "well-defined" and "original" fine-metal workshop active in twelfth century county Roscommon.[70][71][79][80][81][82][83] The shrine was likely commissioned by Bishop "Domnall mac Flannacain Ui Dubthaig", of Elphin,[84] one of the richest episcopal see's in Medieval Ireland,[83] and created by the master gold-craftsman named Irish: 'Mael Isu Bratain Ui Echach' "Mailisa MacEgan", whom O'Donovan says was Abbot of Cloncraff, in county Roscommon,[85][83] though firm evidence for this identification is lacking.[86] The founder and patron Saint of this workshop, might have been St. Assicus of Elphin.[87] Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair was patron of the relic.[32]

Which Saint Manchan is venerated by this shrine? Either the Four Masters identify the wrong Mainchín, [30] or the " shrine of Manchán" was transferred from Mohill, county Leitrim, for some unrecorded reason,[3][4] the difficult journey accounting for the poor condition of the shrine and lost figurines. The fact the Shrine was crafted in county Roscommon, not Clonmacnoise, might strengthen a case for Mohill. Ominously, south county Leitrim was devastated by an "immense" English army c. 1590,[32][84][88] so fleeing Mohill priests must have rescued relics from iconoclasts. Local Mohill folklore states- "In 1621, when St. Manchan's monastery was suppressed, some of the fugitive monks succeeded in bringing the shrine back to Le-Manchan".[63][a 2] Therefore, any shrine transfer from Mohill, county Leitrim,[3][4] probably occurred in the 16th century because the shrine of Manchan was recorded at Lemanaghan church, then situated in "an impassable bog", in the first quarter of the 17th century, c. 1630,[90][91] and is today preserved at the Catholic church of Boher, County Offaly. This transfer remains conjectural unless further research reveals it happened, or there is a discovery of some missing shrine figurines somewhere along the Mohill-Lemanaghan route.

The more pertinent question is the sacral function, and spiritual identity underlying the shrine. Keane proposes the shrine representing a "miniature Ark", an object to be carried on "men's shoulders", an emblem of death to Noah, and those enclosed in the Ark, with their release, on delivery of the Ark, celebrated as Resurrection. Another thought-provoking theory proposes this shrine of Manchán had a political context, representing an attempt by royal patrons to visually cementing political alliances through the purposeful conflation of two neighboring saints, both conveniently named "Manchan".[33] Murray (2013) believes, the argument these reliquaries are multivalent is compelling, when necessary evidence is presented.[92]

- The shrine of Saint Manchan "is inventive", drawing on "a variety of traditions, including the archaic forms of the tomb-shrines to create a new and powerful statement of the saint’s significance in the twelfth century".[33]

- "The crucified figure in the sculptures from a Persian Rock Temple may assist in explaining the mummy-like figures on the Irish shrine. The similarity of the design would seem to confirm the idea that the figures were intended to signify the inmates of the Ark, undergoing the process of mysterious death, which was supposed to be exhibited in Arkite ceremonies".[93]

- "There is a case for the equation of tent and shrine. Latin: papilio, whence Irish: pupall, is primarily the word for butterfly and came to mean tent from a physical resemblance, ie from the fact that the wings in two planes meet at an angle. The term .. Piramis (pyramis), literally "pyramid", and .. the presence of a bearer at each angle, is surely intended to suggest the Ark of the Covenant, a proto-reliquary; pyramis has more than one meaning or connotation .. I suggest that tent-shaped slab shrines were pyramides too".[94]

Lost biography of Manchan

James Ussher claimed to have A Life of St. Manchan of Mohill, apparently written by Richard FitzRalph, presenting Manchan of Mohill as flourishing c. 608, a member of Canons Regular of Augustinian, patron of seven churches, and granted various glebes, lands, fiefs, tithes, etc., since the foundation of the monastery of Mohill in 608.[26][28][95] However, there was no such thing as Canons Regular order of Augustinian, glebes, tithes back in the 5th, 6th and 7th centuries, so these contemporary concepts would not illuminate the life of any Saint Manchan.[22][26] John O'Donovan (scholar), James Henthorn Todd, and others, tried unsuccessfully to locate this book.[26]

Notes and references

Manchan notes

- ↑ Colgan (1647) claimed two Manchán's of Lemanaghan lived in the 7th century, one died c. 664, the other fl. 694,[3] though this claim is disputed.[20][21]

- ↑ Saint Caillin (fl. AD464[32]), wanted to die at the church of Liath Mhór, county Tipperary (24km from a town named Callan). His remains were to be returned to Fenagh, by Manchan, 12 years after his death.

- ↑ The Annals of the Four Masters records "M645.4 ..After the king's return, he granted Tuaim nEirc (i.e. Liath Manchain), with its sub divisions of land, as altarsod",[32] famously intrepreted as "Tuaim nEirc, i. e. Erc's Mound, or tumulus .. the original name of the place where the old church of Lemanaghan .. now stands in ruins",[44] though evidence to support this claim is not presented. Could this instead be a reference to Irish: Baile Uí Eirc "Ballyerk" townland, adjacent to Liath-Mor, county Tipperary?

Plague notes

- ↑ But Mohill (Irish: Maothail "soft or spongy place") is associated with water! The nearby Lough Rinn feeds the Rinn river, which is a tributary of the Shannon river.

- ↑ If the people of Maothaill venerated Saint Manchan in the 6th century then salvation from the horrors of plague, and natural disaster, would be the focus of prayers. Manchán of Athleague (fl. 500), was also invoked for protection from plague. Ann Dooley noted "prayers of saints are a powerful factor in protecting their clients from harms such as the plague, and showing the ability of Irish tradition of sainthood to pick up on the social responsibilities for children left without any legal standing in a stricken community where normal family law has broken down".[62]

Shrine notes

- ↑ The 'Cross of Cong', 'the Aghadoe crosier', ' shrine of the Book of Dimma' and the ' shrine of Manchan' are grouped as originating at the same Roscommon workshop. The Smalls Sword (c. 1100), recently discovered in Wales, has similar Urnes ornamentation.

- ↑ Claims the monastery was suppressed in 1621,[11] or 1592, are wrong. The plantation of Leitrim records an englishman, Henry Crofton, having Mohill estate "settled on him, by his father, 2 June or 1607",[89] and the Irish Annals ominously records "1590, An immense army was sent by the governor against .. Muinter-Eolais, in the beginning of March; and they captured ten hundred cows. And they were that night in Maethail; and .. Liatruim .. Fidhnacha, .. Druim-Oiriallaigh, .. and they brought with them ... nine pledges from Muinter-Eolais, both church and territory. The Breifne was burned".[32][84][88] Clearly 1590 was the effective year of suppression.

Citations

- 1 2 Reynolds 1932, pp. 65-69.

- 1 2 3 Ó Donnabháin 1828, pp. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 Graves 1874, pp. 136.

- 1 2 3 Jewitt 1876, pp. 134.

- 1 2 3 4 O'Clery et al. 1864, pp. 516.

- ↑ Ganly 1865, pp. 439.

- 1 2 Ó Donnabháin 1828, pp. 307.

- 1 2 Cronnelly 1864, pp. 99.

- 1 2 O'Cleary, et. al. 1856, pp. 277.

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'Hanlon 1875, pp. 521.

- 1 2 Monahan 1886, pp. 380.

- ↑ Wenman-Seward 1795, pp. 99.

- ↑ Mac Geoghegan, O'Kelly 1844, pp. 171.

- ↑ Lewis 1837, pp. 376.

- ↑ Colgan 1647, pp. February 14.

- ↑ Healy 1912, pp. 565.

- 1 2 Monahan 1865, pp. 212.

- 1 2 Giraudon 2010, pp. 1.

- ↑ O'Clery et al. 1864, pp. 27.

- ↑ Monahan 1886, pp. 353.

- 1 2 O'Donovan 1838, pp. Letter25.

- 1 2 Lanigan 1829, pp. 30-32.

- 1 2 Baring-Gould, Fisher 1907, pp. 480.

- ↑ Baring-Gould, Fisher 1907, pp. 481.

- ↑ Farmer 2011, pp. 281.

- 1 2 3 4 O'Hanlon 1875, pp. 520.

- 1 2 Lanigan 1829, pp. 31.

- 1 2 Harleian Trustees 1759, pp. 66.

- ↑ Wall 1905, pp. 83.

- 1 2 Stokes 1868, pp. 287.

- 1 2 3 Mac Niocaill 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 AFM.

- 1 2 3 Overbey 2012, pp. 41.

- ↑ Mears 1722, pp. 379.

- ↑ Comerford 1755, pp. 138.

- ↑ Cobbett 1827, pp. 213.

- ↑ Cobbett 1834, pp. 230.

- ↑ Walsh 1854, pp. 519.

- 1 2 Gormáin, Stokes 1895, pp. 380.

- 1 2 O'Hanlon 1875, pp. 522, 524.

- ↑ Whelan.

- ↑ Ó Donnabháin 1828, pp. 13,291.

- ↑ O' Rian 2016, pp. 27.

- ↑ O'Clery et al. 1864, pp. 261.

- ↑ Plummer 2010, pp. 1.

- ↑ Lanigan 1829, pp. 57.

- 1 2 Bambury, Beechinor 2000, pp. U535.1, U537.3.

- 1 2 Bambury, Beechinor 2000, pp. U536.3, U539.1, U545.1.

- ↑ Mac Airt 2000, 2008.

- ↑ O'Hanlon 1875, pp. 522.

- ↑ Mark Redknap 2001, pp. 12.

- ↑ Haley 2002, pp. 108.

- ↑ Haley 2002, pp. 117.

- ↑ Gaffey 1975, pp. Tamlaghavally.

- ↑ Dooley 2007, pp. 216.

- ↑ Dooley 2007, pp. 217.

- ↑ Haley 2002, pp. 105.

- ↑ Haley 2002, pp. 111.

- ↑ Haley 2002, pp. 107.

- 1 2 Haley 2002, pp. 114.

- ↑ O Rodaighe 1700, pp. 5.

- ↑ Dooley 2007, pp. 225.

- 1 2 Irish Press 8th May 1939, pp. 7.

- ↑ St. Manchan's School 2010.

- ↑ Boyd 1938, pp. 226.

- ↑ St. Manchan's School 2016.

- ↑ Lynch, Kelly 1848, pp. 75.

- ↑ O'Cleary, et. al. 1856, pp. 1157.

- 1 2 3 4 Corkery 1961, pp. 6-8.

- 1 2 De Paor 1979, pp. 49-50.

- 1 2 Ó Floinn 1987, pp. 179-187.

- ↑ Wilson & 2014, pp. 141-145.

- 1 2 Murray 2003, pp. 177.

- ↑ Stokes 1894, pp. 113.

- ↑ Graves 1874, pp. 146.

- ↑ W J Edmondston Scott 1934, p. 126.

- ↑ Stokes & 1868 quoting a Petrie manuscript, pp. 285.

- 1 2 3 Joyce 1903, pp. 182, 183, 203.

- ↑ Murray 2003, pp. 178.

- ↑ Hourihane 2012, pp. 225.

- ↑ Edwards 2013, pp. 147.

- ↑ Karkov, Ryan, Farrell 1997, pp. 269.

- 1 2 3 Kelly 1909, pp. 1.

- 1 2 3 Hennessy 2008.

- ↑ Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) 1977, pp. 190.

- ↑ Murray 2006, pp. 53.

- ↑ Kelly 1902, pp. 291-292.

- 1 2 Hynes & 1931 45-46.

- ↑ Debretts 1824, pp. 986.

- ↑ Graves 1874, pp. 137.

- ↑ Kendrick, Senior 1937.

- ↑ Murray 2013, pp. 280.

- ↑ Keane 1867, pp. 348.

- ↑ Bourke 2012, pp. 5.

- ↑ O'Donovan, O'Flanagan 1929, pp. 82.

Primary sources

- O'Hanlon, John (1875). Lives of the Irish Saints : with special festivals, and the commemorations of holy persons (PDF). Internet Archive is non-profit library of millions of free books, and more.: Dublin : J. Duffy. p. 1. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Corkery, Sean (1961). "The Shrine of Saint Manchan". 12 (3) (The Furrow, ed.): 6–8. JSTOR 27658066. (subscription required)

- Mac Niocaill, Gearóid (2010). The Annals of Tigernach. CELT online at University College, Cork, Ireland.: Dublin : Printed for the Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society by A. Thom. p. 1. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Annals of the Four Masters, ed. & tr. John O'Donovan (1856). Annála Rioghachta Éireann. Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters... with a Translation and Copious Notes. 7 vols (2nd ed.). Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. CELT editions. Full scans at Internet Archive: Vol. 1; Vol. 2; Vol. 3; Vol. 4; Vol. 5; Vol. 6; Indices.

Secondary sources

- Graves, James (1874). "The Church and Shrine of St. Manchán". The Journal of the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland. 3: 134–50. JSTOR 25506649. (subscription required)

- Mark Redknap, ed. (2001). "Pattern and Purpose in Insular Art: Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Insular Art Held at the National Museum & Gallery, Cardiff 3-6 September 1998" (illustrated, Digitized 2009(Original from the University of Michigan) ed.). Oxbow: 12. ISBN 1842170589.

- O'Clery, Michael; O'Donovan, John; Reeves, William; Todd, James Henthorn (1864). The martyrology of Donegal : a calendar of the saints of Ireland (PDF). Oxford University: Dublin : Printed for the Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society by A. Thom. p. 516. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- O'Donovan, John; O'Flanagan, Michael (1929). Letters Containing Information Relative to the Antiquities of the Counties [of Ireland: Cavan and Leitrim. Volume 3 of Letters Containing Information Relative to the Antiquities of the Counties [of Ireland, Great Britain. Ordnance Survey. Great Britain. Ordnance Survey,.

- Ó Donnabháin, Sean (1828). Book of Fenagh, Translation and Copious Notes (PDF). Fenagh, Leitrim, Ireland: Maolmhordha Mac Dubhghoill Uí Raghailligh. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- O' Rian, Dr Padraig (2016). "Saint Caillin and the book of Fenagh, 1516-2016" (PDF) (14 September 2016 ed.). Royal Irish Academy. p. 27.

- Monahan, John (1865). "The Irish Ecclesiastical Record" (PDF) (Volume 7 ed.). Dublin : John F. Fowler: 212. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Kelly, J. J. (1902). "The Irish Ecclesiastical Record, A monthly journal, under Episcopal Sanction" (PDF) (Volume 11 XI ed.). Dublin: Browne & Nolan, Limited, Nassau-Street: 291–292. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Wall, James Charles (1905). J. Charles Cox, ed. Shrines of Britsh Saints, with numerous illustrations (PDF). Methuen & Co., 36 Essex Street WC, London, England. p. 83. Retrieved 10 October 2016. (subscription required)

- Lanigan, John (1829). The Irish Church, ed. An Ecclesiastical History of Ireland, from the first introduction of Christianity among the Irish, to the beginning of the thirteenth century. Volume III (second ed.). Dublin: J. Cumming, 16, L. Ormond-Quay; London: Simpkin and Marshall; Edinburgh: R. Cadell and Co. pp. 30–32. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Stokes, William (1868). The Life and Labours in Art and Archaeology, of George Petrie (Reprinted 2014 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 287. ISBN 9781108075701. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Gormáin, Félire Húi; Stokes, Whitley (1895). The martyrology of Gorman : edited from a manuscript in the Royal Library Brussels (PDF). London : [Henry Bradshaw Society]. p. 380. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Kelly, J. J. (1909). Catholic Online Catholic Encyclopedia Digital version, ed. "Elphin. In the Catholic Encylopedia" (Volume 5 ed.). Robert Appleton Company New York, NY. p. 1. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Karkov, Catherine E.; Ryan, Michael; Farrell, Robert T. (1997). "The Insular Tradition: Theory and Practice in Transpersonal Psychotherapy". SUNY Press: 269. ISBN 9780791434567. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Comerford, T. (1755). The History of Ireland: From the Earliest Account of Time, to the Invasion ... Laurence Flin. p. 138. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- Mears, William (1722). Monasticon Hibernicum: Or, The Monastical History of Ireland ... London: Lamb without Temple-bar. p. 379.

- Edwards, Nancy (2013). The Archaeology of Early Medieval Ireland. Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 9781135951498. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Healy, John (1912). Insula Sanctorum Et Doctorum Or Ireland's Ancient Schools And Scholars (PDF). Dublin : Sealy, Bryers & Walker ; New York : Benziger. p. 564. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Lynch, John (1848). Matthew Kelly, ed. Cambrensis Eversus, the history of ancient Ireland vindicated : the religion, laws and civilization of her people exhibited in the lives and actions of her kings, princes, saints, bishops, bards, and other learned men ... (PDF) (Volume 1: 1870 ed.). University of Toronto: Dublin: Printed for the Celtic Society by Goodwin, son, and Wethercott, 79, Marlborough-street. p. 75. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Mac Geoghegan, James; O'Kelly, Patrick (1844). The History of Ireland, Ancient and Modern: Taken from the Most Authentic Records, and Dedicated to the Irish Brigade. Dublin: James Duffy, 25 Anglesea Street. p. 171. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Keane, Marcus (1867). The towers and temples of ancient Ireland; their origin and history discussed from a new point of view (PDF). Dublin: Hodges, Smith. p. 348. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Jewitt, LLewellynn (1876). Ancient Irish Art, The shrine of St. Manchan. (PDF). Volume XV (The Art Journal ed.). London: Virtue & Company, Limited. p. 134. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Hourihane, Colum (2012). The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture. Volume 2. OUP USA. p. 225. ISBN 9780195395365. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Monahan, John (1886). Records relating to the dioceses of Ardagh and Clonmacnoise (PDF) (forgotton books, copyright 2016 FB&c Ltd. ed.). Dublin: M. H. Gill and Son, O'Connell Street. pp. 353, 380.

- Murray, Griffin (2006). "The Cross of Cong and some aspects of goldsmithing in pre-Norman Ireland". 40, Part 1 (The Art of the Early Medieval Goldsmith ed.). The Journal of the Historical Metallurgy Society: 53. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- Hennessy, William M. (2008). "Annals of Lough Ce" (Electronic edition compiled by the CELT Team (2002)(2008) ed.). CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts: a project of University College Cork College Road, Cork, Ireland—http://www.ucc.ie/celt. pp. LC1137.10.

- Ó Floinn, Raghnall (1987). Michael Ryan, ed. "In Ireland and Insular Art A.D. 500–1200: Proceedings of a Conference at University College Cork, 31 October–3 November 1985" (Schools of Metalworking in Eleventh- and Twelfth-Century Ireland ed.). Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, International Specialized Book Service Incorporated: 179–187. ISBN 9780901714541.

- Joyce, Patrick Weston (1903). A social history of ancient Ireland : treating of the government, military system, and law ; religion, learning, and art ; trades, industries, and commerce ; manners, customs, and domestic life, of the ancient Irish people (PDF). Volume II. Dublin: M. H. Gill & Son, Ltd. London ; New York : Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 182, 183, 203. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- Wenman-Seward, William (1795). Topographia Hibernica: Or The Topography of Ireland, Antient and Modern. Giving a Complete View of the Civil and Ecclesiastical State of that Kingdom; with Its Antiquities, Natural Curiosities, Trade, Manufactures, Extent and Population (Digitized 2007 (original from the New York Public Library) ed.). Dublin: Alex Steward, No. 86, Bride-Street.

- Harleian Trustees (1759). Harleian collection, No. 1802 (Irish MS of the Four Gospels). A Catalogue of the Harleian Collection of Manuscripts, purchased by authority of the Parliament, for the use of the Publick, and preserved in the British Museum, Volume I (Digitized 2016, original in Austrian National Library ed.). Original published by Order of the Trustees. London - printed by Dryden Leach, MDCCLIX.

- Reynolds, D (1932). "Journal Ardagh and Clonmacnoise Antiquaties Society I". iii (St. Manchan (Managhan) of Mohill and Lemanaghan (Offaly) ed.): 65–69.

- Murray, Griffin (2003). Lost and Found: The Eleventh Figure on St Manchan's Shrine. London: Lamb without Temple-bar. p. 178. JSTOR 25509113.

- Lewis, Samuel (1837). A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. Volume 1. London: S. LEwis & Co. 87, Aldersgate Street. p. 376.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), ed. (1977). Treasures of Early Irish Art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D.: From the Collections of the National Museum of Ireland, Royal Irish Academy, Trinity College, Dublin (illustrated, reprint ed.). Metropolitan Museum of Art,. p. 190. ISBN 0870991647.

- Bambury, Pádraig; Beechinor, Stephen (2000). "The Annals of Ulster" (Electronic edition compiled by the CELT Team (2000) ed.). CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts: a project of University College Cork College Road, Cork, Ireland—http://www.ucc.ie/celt. pp. U536.3, U539.1, U545.1.

- Mac Airt, Seán (2000–2008). "Annals of Inisfallen" (Electronic edition compiled by Beatrix Färber ed.). CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts: a project of University College Cork College Road, Cork, Ireland—http://www.ucc.ie/celt.

- Stokes, Margaret (1894). Early Christian Art in Ireland (PDF). Part I. London: Chapman and Hall, Limited, 11 Henrietta Street, Convent Garden. p. 113.

- Ganly, William (1865). The Holy Places of Connemara (PDF). The Irish ecclesiastical record, Volume 10. Dublin : John F. Fowler. pp. 432–440.

- Cobbett, William (1827). A History of the Protestant "Reformation," in England and Ireland: Showing how that Event Has Impoverished and Degraded the Main Body of the People in Those Countries, in a Series of Letters, Addressed to All Sensible and Just Englishmen. Containing a list of the abbeys, priories ...,. Volume 2 (Digitized 2010 (original from the Bavarian State Library) ed.). Clement.

- Cobbett, William (1834). A History of the Protestant Reformation in England and Ireland ... in a Series of Letters ... to which is Now Added, Three Letters. Volume 2. J. Doyle. p. 230.

- Walsh, Thom (1854). History of the Irish Hierarchy: With the Monasteries of Each County, Biographical Notices of the Irish Saints, Prelates, and Religious (Digitized 2008 (original from the Bavarian State Library) ed.). Sadlier.

- O Rodaighe, Tadhg (1700). "Tadhg O Rodaighe to [Edward Lhwyd]" (PDF). Dublin, Trinity College Dublin, a document bound into MS 1318 (donated from Edward Lhuyd collection): Rev. J. H. Todd, D. D., ‘Autograph Letter of Thady O’Roddy’, The Miscellany of the Irish Archaeological Society 1 (1846), 112–125. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- Giraudon, Professeur Daniel (2010). "La vache merveilleuse de Saint Manchàn" (PDF) (7th March 2010 ed.). Center for Breton and Celtic Research.

- O'Clery, Michael; O'Clery, Cucogry; O'Mulconry, Ferfeasa; O'Duigenan, Cucogry; O'Clery, Conary (1856). John O'Donovan, ed. Annala Rioghachta Eireann : Annals of the kingdom of Ireland (PDF). Volume 1. Dublin : Hodges, Smith.

- Plummer, Charles (2010). "Litany of Irish Saints II" (2008, 2nd draft 2010, "an old ancient vellum book" ed.). CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts: a project of University College, Cork College Road, Cork, Ireland—http://www.ucc.ie/celt.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine; Fisher, John (1907). Lives of British Saints: The Saints of Wales and Cornwall, and such Irish Saints as have decidations in Britain (PDF). Volume III. London: The Honourable Society of Cymmrodorian by C.J. Clark.

- Cronnelly, Richard Francis (1864). Irish Family History. Volume 1 (Digitized 2008 (original from University of Wisconsin - Madison) ed.). Goodwin, son, and Nethercott.

- Bourke, Cormac (2012). "Defining sacred space" (PDF). How did influence spread across Scotland and Ireland?. Belfast: Iona Research Conference: 5.

Bibliography

- Colgan, John (1647). Acta Triadis Thaumaturgae. Volume III. p. a, n. 67.

- Colgan, John (1645). Acta sanctorum veteris et maioris Scotiæ, seu Hiberniæ sanctorum insulae, partim ex variis per Europam MS. Codd. exscripta, partim ex antiquis monumentis & probatis authoribus eruta & congesta; omnia notis & appendicibus illustrata, per R. P. F. Ioannem Colganum ... Nunc primum de eisdem actis iuxta ordinem mensium & dierum prodit tomus primus, qui de sacris Hiberniæ antiquitatibus est tertius ianuarium, febrarium, & martium complectens (Digital version ed.). Alessandrina Library, Rome: apud Euerardum de Witte, 1645.

- Overbey, Karen (2012). Sacral Geographies: Saints, Shrines, and Territory in Medieval Ireland. Brepols Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 9782503527673.

- W J Edmondston Scott, ed. (1934). "Celtic Forum: A Journal of Celtic Opinion". 1. Celtic Historical Society, Toronto, Canada: 126.

- De Paor, Marie (1979). "Early Irish Art". Aspects of Ireland 3 (reprinted 1983 ed.). Department of Foreign Affairs. ISBN 0906404037.

- Murray, Griffin (2013). "Review, Karen Eileen Overbey, Sacral geographies: saints, shrines, and territory in medieval Ireland. Studies in the Visual Cultures of the Middle Ages 2". Peritia. Peritia. (24-25): 375–380. doi:10.1484/J.PERIT.5.102758.

- Dooley, Ann (2007). Lester K. Little, ed. The Plague and Its Consequences in Ireland. Plague and the End of Antiquity, The PAndemic of 541-750. Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–230. ISBN 0511335261.

- Wilson, D. M. (2014). D. A. Pearsall; R. A. Waldron, eds. An Early Representation of St Olaf. Medieval Literature and Civilization: Studies in Memory of G.N. Garmonsway (Bloomsbury Academic Collections: English Literary ed.). A&C Black. pp. 141–145. ISBN 1472512510.

- Haley, Gene C. (2002). "Tamlachta: The Map of Plague Burials and Some Implications for Early Irish History". 22, Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium. Department of Celtic Languages & Literatures, Harvard University: 96–140. JSTOR 40285165.

- Debretts (1824). Debrett's baronetage, knightage, and companionage (PDF). Volume 2 (5 ed.). London, Odhams Press. p. 986.

Not consulted (tbd)

- Kendrick, T. D.; Senior, Elizabeth (1937). "Archaeologia, Volume 86". Archaeologia (St. Manchan's Shrine ed.). Oxford: printed by John Johnson for the Society of Antiquaries of London. 86: 105–118. doi:10.1017/S0261340900015381. (subscription required)

- Breen, Aidan (2010). "Manchán, Manchianus, Manchíne". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Cambridge University Press.

- Harbison, Peter, H. Potterton, J. Sheehy, eds. (1978). Irish Art and Architecture: From Prehistory to the Present. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

External links

- Henry, Françoise (1902). "Notes and sketches relating to St. Manchan's Shrine, Roscommon and Clonmacnoise, and the Shrine of St. Meodhoc.". UCD School of History and Archives. UCD Archives, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland: University College Dublin Library.

- "Irish Press" (8th May 1939 ed.). 1939. p. 7. (subscription required)

- O’Donovan, John (1838). "Letter no. 25, Ordnance Survey Letters King's County".

- Boyd, D (1938). "Fighting". duchas.ie. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- Whelan, Michael. "Monastery at Mohill". Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- St. Manchan's School (2010). "St. Manchan's Primary School, Mohill". Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- St. Manchan's School (2016). "February 25th - ST. Manchan's Day". Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- Mac Phaidín Uí Mhaoil Chonaire, Muirgheas (1516). Leabar Chaillín / Leabar Fidhnacha. Dublin, Ireland: Tadhg Ó Rodaighe. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- Gaffey, Matt (1975). "Place names of Mohill". Michael Whelan, mohillparish.ie.

- "Mohill Parish". Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Tamlaght More Townland, Co. Leitrim".

- "Tamlaght Beg Townland, Co. Leitrim".

- "Tamlaghtavally Townland, Co. Leitrim".

- "Plague burial townland's in Airgíalla (query)". townlands.ie.