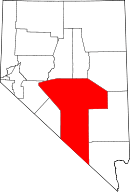

Manhattan, Nevada

| Manhattan, Nevada | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

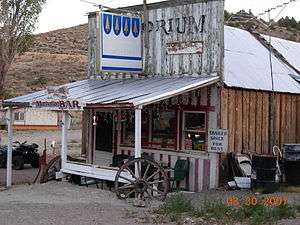

|

Sign at the east entrance to Manhattan | |

| Nickname(s): Town of New Beginnings | |

| Motto: Embracing a better Manhattan | |

| Coordinates: 38°32′20″N 117°04′30″W / 38.53889°N 117.07500°WCoordinates: 38°32′20″N 117°04′30″W / 38.53889°N 117.07500°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Nevada |

| County | Nye |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.28 sq mi (0.72 km2) |

| • Land | 0.28 sq mi (0.72 km2) |

| • Water | 0 sq mi (0 km2) |

| Elevation | 7,000 ft (2,000 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 124 |

| • Density | 450/sq mi (170/km2) |

| Time zone | Pacific (PST) (UTC-8) |

| • Summer (DST) | PDT (UTC-7) |

Manhattan is a small town in Nye County, Nevada, located at the end of Nevada State Route 377 about 50 miles (80 km) north of Tonopah, the county seat.

It originally was founded in 1867 as part of the silver mining boom. George Wheeler found the district abandoned in 1871.[1] Then, in 1905, as part of the gold boom when "4,000 people flood(ed) into the region". The Nye and Ormsby County Bank, the only stone structure to be built in the town, was erected in 1906, but a decline followed the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the 1907 depression.[2]

The bank was forced to close. However, another boom in 1909 resulted in mining continuing into the late 1940s.[3] Major mining operations opened and operated through the 1970s to the 1990s but production has relatively recently scaled back significantly.[4]

Regional geology

The Big Smoky Valley is similar to many of the desert valleys in Nevada, characterized by flanking mountain ranges running north to south. Big Smoky Valley is bounded to the south by Lone Mountain, and the east and west by the Toquima and the Toiyabe Ranges, respectively. The valley floor consists primarily of alluvial fans composed of small poorly assorted gravels.

Meta-sedimentary and granitic wastes predominate the Manhattan and Kingston fans while quartz sands derived from granites, predominate in the axial part of the valley between Charnock Springs and Round Mountain and most of the steep slope adjacent to Lone Mountain. Grit derived from Tertiary lavas supplied by the southern part of the Toiyabe and Shoshone Ranges is also abundant and widely distributed.[5]

Limestone, slate, schist, and quartzite aggregating several thousand feet in thickness and ranging in age from lower Cambrian to Carboniferous are the oldest rocks found in this region. Although they have a wide range in age, no unconformity has been found between two successive formations. Since their deposition they have been extensively deformed, eroded, intruded by lavas, and largely covered by igneous bodies and sedimentary deposits. Originally they probably covered the entire region, but at present they are found over extensive areas only in the Toiyabe, Toquima, Silver Peak, and Lone Mountain ranges.[5]

Igneous rocks in the Big Smoky Valley are predominantly pre-Quaternary. Eruptive formations, consisting of rhyolite and minor amounts of basalt and rocks of intermediate composition with associated tuffs and breccias, are exposed over extensive areas in all of the ranges bordering the valley. They differ widely in age but were probably formed during the Tertiary period. Several great bodies of granitic rock are also found in the valley. They are intrusive in the Paleozoic strata but older than the Tertiary eruptive rocks. A large granite mass occupies the lofty central part of the Toquima Range particularly in the region of Round Mountain. Another granite mass forms the main part of Lone Mountain.[5]

Big Smoky Valley, in the late Pleistocene, was occupied by two large lakes. The lakes were contained in the lowest parts of the northern and southern reaches of the valley and are known as Lake Toiyabe and Lake Tonopah, respectively. Shore features, such as gravelly beaches and embankments still exist in the valley while the former lake sites are presently occupied by alkali flats. Stratified beds of the former lakes are not exposed.[5]

On the eastern alluvial slopes of the Toiyabe Range, there are many escarpments which face the valley and are believed to be due to recent faulting (Meinzer, 1917).

Local geology

Considerable volcanic activity and caldera development initiated in the Manhattan Caldera Complex about 16 million years ago in the Toquima mountains north of Manhattan Gulch. It is likely that gold was transported by solutions in a hydrothermal cell from an igneous intrusion, and perhaps from country rock, to the host rock. When the gold at Manhattan was deposited, approximately 16 million years ago, the hydrothermal cells may have operated at some distance beneath the Earth’s surface. Over time, however, the upper formations at Manhattan eroded, as evidenced by the well-rounded and low-lying hills in the area, and the gold they contained was washed down Manhattan Gulch and deposited in gravel.[6]

Manhattan Gulch averages 300 feet (91 m) wide with a grading of approximately four percent to the east. Rimrock slopes around the gulch range from 30 to 50 percent. Depth of the gravels ranges from 10 to 100 feet (3 to 30 m) with an average of about 30 feet (9 m). Approximately 60 percent of the gravel is larger than 1 inch (2.5 cm) with the rest being primarily sand and smaller gravel. The bedrock of the Gulch is composed predominantly of schist and shale.[7]

Elevations range from about 5,800 feet (1,800 m) above mean sea level (AMSL) at the west end of the gulch area to above 7,000 feet (2,100 m) near the town of Manhattan.

Local vegetation

Vegetation transect surveys were conducted in Manhattan Gulch in spring 2009. In the lower Manhattan Gulch area, below 6,600 feet (2,000 m), shrub growth is dominant comprising about 80 percent of species composition, followed by grasses with about 15 percent of species composition, followed by various forbs (MINES Group, 2009). Common shrub species include black sage (Artemisia nova), green rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus viscidiflorus) and bud sage (Artemisia spinescens). Grasses include galleta (Hilaria jamesii) and Indian ricegrass (Acnatherum hymenoides). Further west up Manhattan Gulch and toward the town of Manhattan, trees become dominant, with Juniperus osteosperma and Pinus monophylla being prevalent (MINES Group, 2009).

Present day

As of 2005, the population of Manhattan was 124.[8] There are two bars, The Miner's Saloon and The Manhattan Bar and Motel.

Within about 10 miles (16 km) north along State Route 376 active placer gold mining is taking place on a small scale.

Climate

Manhattan experiences a semi-arid climate with short, warm summers and long, cold winters. Manhattan does not have a wet or dry season. Precipitation is distributed equally throughout the year. Due to Manhattan's high elevation, summer high temperatures rarely exceed 90 °F (32 °C). Manhattan's high elevation also makes the diurnal temperature variation substantial. Nights are cool in the summer. While very rare in summer months, Manhattan has experienced temperatures below freezing in every month of the year. Winters are long and can be bitterly cold.

| Climate data for Manhattan, Nevada (Elevation 7,000ft) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 63 (17) |

64 (18) |

70 (21) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

93 (34) |

96 (36) |

95 (35) |

92 (33) |

80 (27) |

70 (21) |

60 (16) |

96 (36) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 37.5 (3.1) |

40.1 (4.5) |

46.5 (8.1) |

53.6 (12) |

60.9 (16.1) |

71.2 (21.8) |

80.1 (26.7) |

79.8 (26.6) |

69.9 (21.1) |

59.0 (15) |

44.5 (6.9) |

37.4 (3) |

56.3 (13.5) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 13.8 (−10.1) |

16.1 (−8.8) |

21.3 (−5.9) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

39.3 (4.1) |

47.4 (8.6) |

47.3 (8.5) |

38.5 (3.6) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

13.6 (−10.2) |

28.4 (−2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −15 (−26) |

−20 (−29) |

−4 (−20) |

0 (−18) |

10 (−12) |

17 (−8) |

20 (−7) |

27 (−3) |

15 (−9) |

−3 (−19) |

−8 (−22) |

−30 (−34) |

−30 (−34) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.99 (25.1) |

0.93 (23.6) |

1.12 (28.4) |

0.69 (17.5) |

0.97 (24.6) |

0.56 (14.2) |

0.94 (23.9) |

0.60 (15.2) |

0.79 (20.1) |

0.58 (14.7) |

0.73 (18.5) |

0.69 (17.5) |

9.89 (251.2) |

| Source: The Western Regional Climate Center[9] | |||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Carlson, Helen S. (1985). Nevada place names : a geographical dictionary. Reno: University of Nevada Press. p. 163. ISBN 0-87417-094-X.

- ↑ placard on the ruins of the bank building

- ↑ Rinella, p.52

- ↑ (Kautz, 2007)

- 1 2 3 4 Meinzer, O.E. (1917). Big Smoky, Clayton, and Alkali Spring Valleys, Nevada. Washington: United States Geological Survey. Washington Government Printing Office.

- ↑ McCracken, R.D. (1997). A History of Smoky Valley, Nevada. Tonopah, NV: Central Nevada Historical Society.

- ↑ Vanderburg, W.O. (1936). Placer Mining in Nevada. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Bulletin 30(4).

- ↑ Nye County Demographics

- ↑ "Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

References

- Kral, V.E. 1951. Mineral Resources of Nye County, Nevada. University of Nevada Bulletin. 45(3).

- McCracken, R.D. 1997. A History of Smoky Valley Nevada. Central Nevada Historical Society. Tonopah, NV.

- Meinzer, O.E. 1917. Big Smoky, Clayton, and Alkali Spring Valleys, Nevada. United States Geological Survey. Washington Government Printing Office.

- Rinella, Heidi Knapp, Off The Beaten Path: Nevada, Guildford, CT: The Globe Pequot Press, 2007 ISSN 1537-3304

- Thomson, David, In Nevada: The Land, The People, God, and Chance, New York: Vintage Books, 2000. ISBN 0-679-77758-X

- Vanderburg, W.O. 1936. Placer Mining in Nevada. University of Nevada Bulletin. 30(4). May 15, 1936.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manhattan, Nevada. |