Marquis de Sade

| Marquis de Sade | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Donatien Alphonse François de Sade by Charles Amédée Philippe van Loo. The drawing dates to 1760, when de Sade was nearly 20 years old, and is the only known authentic portrait of the Marquis. | |

| Born |

Donatien Alphonse François de Sade 2 June 1740 Paris, France |

| Died |

2 December 1814 (aged 74) Charenton, Val-de-Marne, France |

| Notable work |

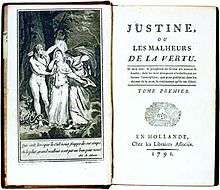

The 120 Days of Sodom (1789) Justine (1791) Philosophy in the Bedroom (1795) Juliette (1799) |

| Spouse(s) | Renée-Pélagie Cordier de Launay (m. 1763–1810); her death |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophers |

| School | Libertine, Erotic |

Main interests | Pornography, erotism, politics |

Notable ideas | Sadomasochism |

Donatien Alphonse François, Marquis de Sade (2 June 1740 – 2 December 1814) (French: [maʁki də sad]), was a French aristocrat, revolutionary politician, philosopher, and writer, famous for his libertine sexuality. His works include novels, short stories, plays, dialogues, and political tracts; in his lifetime some were published under his own name, while others appeared anonymously and de Sade denied being their author. De Sade is best known for his erotic works, which combined philosophical discourse with pornography, depicting sexual fantasies with an emphasis on violence, criminality, and blasphemy against the Catholic Church. He was a proponent of extreme freedom, unrestrained by morality, religion, or law. The words sadism and sadist are derived from his name.

De Sade was incarcerated in various prisons and an insane asylum for about 32 years of his life: 11 years in Paris (10 of which were spent in the Bastille), a month in the Conciergerie, two years in a fortress, a year in Madelonnettes Convent, three years in Bicêtre Hospital, a year in Sainte-Pélagie Prison, and 12 years in the Charenton asylum. During the French Revolution he was an elected delegate to the National Convention. Many of his works were written in prison.

Life

Early life and education

The Marquis de Sade was born in the Hôtel de Condé, Paris, to Jean Baptiste François Joseph, Count de Sade and Marie Eléonore de Maillé de Carman, cousin and Lady-in-waiting to the Princess of Condé on 2 June 1740. He was his parents' only surviving child.[1] He was educated by an uncle, the Abbé de Sade. In de Sade's youth, his father abandoned the family; his mother joined a convent.[2] He was raised with servants who indulged "his every whim," which led to him becoming "known as a rebellious and spoiled child with an ever-growing temper."[2]

Later in his childhood, de Sade was sent to the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris,[2] a Jesuit college, for four years.[1] While at the school, he was tutored by Abbé Jacques-François Amblet, a priest.[3] Later in life, the Abbé testified at one of de Sade's trials, saying that de Sade had a "passionate temperament which made him eager in the pursuit of pleasure" but had a "good heart."[3] At the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, he was subjected to "severe corporal punishment," including "flagellation," and he "spent the rest of his adult life obsessed with the violent act."[2] At age 14, de Sade began attending an elite military academy.[1]

At age 15, he was commissioned as a sub-lieutenant on 14 December 1755 after 20 months of training, becoming a soldier.[3] After 13 months as a sub-lieutenant, he was commissioned to the rank of cornet in the Brigade de S. André of the Comte de Provence's Carbine Regiment.[3] He eventually became Colonel of a Dragoon regiment and fought in the Seven Years' War. In 1763, on returning from war, he courted a rich magistrate's daughter, but her father rejected his suitorship and, instead, arranged a marriage with his elder daughter, Renée-Pélagie de Montreuil; that marriage produced two sons and a daughter.[4] In 1766, he had a private theatre built in his castle, the Château de Lacoste, in Provence. In January 1767, his father died.

Title and heirs

The men of the de Sade family alternated between using the marquis and comte (count) titles. His grandfather, Gaspard François de Sade, was the first to use marquis;[5] occasionally, he was the Marquis de Sade, but is identified in documents as the Marquis de Mazan. The de Sade family were noblesse d'épée, claiming at the time the oldest, Frank-descended nobility, so, assuming a noble title without a King's grant, was customarily de rigueur. Alternating title usage indicates that titular hierarchy (below duc et pair) was notional; theoretically, the marquis title was granted to noblemen owning several countships, but its use by men of dubious lineage caused its disrepute. At Court, precedence was by seniority and royal favor, not title. There is father-and-son correspondence, wherein father addresses son as marquis.

For many years, de Sade's descendants regarded his life and work as a scandal to be suppressed. This did not change until the mid-twentieth century, when the Comte Xavier de Sade reclaimed the marquis title, long fallen into disuse, on his visiting cards,[6] and took an interest in his ancestor's writings. At that time, the "Divine Marquis" of legend was so unmentionable in his own family that Xavier de Sade only learned of him in the late 1940s when approached by a journalist.[7] He subsequently discovered a store of de Sade's papers in the family château at Condé-en-Brie, and worked with scholars for decades to enable their publication.[8] His youngest son, the Marquis Thibault de Sade, has continued the collaboration. The family have also claimed a trademark on the name.[9] The family sold the Château de Condé in 1983.[10] As well as the manuscripts they retain, others are held in universities and libraries. Many, however, were lost in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A substantial amount were destroyed after de Sade's death at the instigation of his son, Donatien-Claude-Armand.[11]

Scandals and imprisonment

De Sade lived a scandalous libertine existence and repeatedly procured young prostitutes as well as employees of both sexes in his castle in Lacoste. He was also accused of blasphemy, a serious offense at that time. His behavior included an affair with his wife's sister, Anne-Prospère, who had come to live at the castle.[8]

Beginning in 1763, de Sade lived mainly in or near Paris. Several prostitutes there complained about mistreatment by him and he was put under surveillance by the police, who made detailed reports of his activities. After several short imprisonments, which included a brief incarceration in the Château de Saumur (then a prison), he was exiled to his château at Lacoste in 1768.[12]

The first major scandal occurred on Easter Sunday in 1768, in which de Sade procured the sexual services of a woman, Rose Keller,[13] a widow-beggar who approached him for alms. He told her she could make money by working for him—she understood her work to be that of a housekeeper. At his chateau at Arcueil, de Sade ripped her clothes off, threw her on a divan and tied her by the four limbs. Then he whipped her, made various incisions on her body into which he poured hot wax, and then beat her. He repeated this process seven or eight times, when she finally escaped by climbing out of a second-floor window and running away. At this time, la Présidente, de Sade's mother-in-law, obtained a lettre de cachet (a royal order of arrest and imprisonment, without stated cause or access to the courts) from the King, excluding de Sade from the jurisdiction of the courts. The lettre de cachet would later prove disastrous for the marquis.[14]

In 1772, an episode in Marseille involved the non-lethal poisoning of prostitutes with the supposed aphrodisiac Spanish fly and sodomy with Latour, his manservant. That year, the two men were sentenced to death in absentia for sodomy and the poisoning. They fled to Italy, de Sade taking his wife's sister with him. De Sade and Latour were caught and imprisoned at the Fortress of Miolans in late 1772, but escaped four months later.

De Sade later hid at Lacoste, where he rejoined his wife, who became an accomplice in his subsequent endeavors.[8] He kept a group of young employees at Lacoste, most of whom complained about sexual mistreatment and quickly left his service. De Sade was forced to flee to Italy once again. It was during this time he wrote Voyage d'Italie. In 1776, he returned to Lacoste, again hired several servant girls, most of whom fled. In 1777, the father of one of those employees went to Lacoste to claim his daughter, and attempted to shoot the Marquis at point-blank range, but the gun misfired.

Later that year, de Sade was tricked into going to Paris to visit his supposedly ill mother, who in fact had recently died. He was arrested there and imprisoned in the Château de Vincennes. He successfully appealed his death sentence in 1778, but remained imprisoned under the lettre de cachet. He escaped but was soon recaptured. He resumed writing and met fellow prisoner Comte de Mirabeau, who also wrote erotic works. Despite this common interest, the two came to dislike each other intensely.[15]

In 1784, Vincennes was closed, and de Sade was transferred to the Bastille. On 2 July 1789, he reportedly shouted out from his cell to the crowd outside, "They are killing the prisoners here!", and a disturbance began to foment.[8] Two days later, he was transferred to the insane asylum at Charenton near Paris. The storming of the Bastille, a major event of the French Revolution, would occur a few days later on 14 July.

He had been working on his magnum opus Les 120 Journées de Sodome (The 120 Days of Sodom). To his despair, he believed that the manuscript was lost during his transfer, but he continued to write.[8]

In 1790, he was released from Charenton after the new National Constituent Assembly abolished the instrument of lettre de cachet. His wife obtained a divorce soon after.

Return to freedom, delegate to the National Convention, and imprisonment

During Sade's time of freedom, beginning in 1790, he published several of his books anonymously. He met Marie-Constance Quesnet, a former actress, and mother of a six-year-old son, who had been abandoned by her husband. Constance and de Sade would stay together for the rest of his life.

He initially ingratiated himself with the new political situation after the revolution, supported the Republic,[16] called himself "Citizen de Sade", and managed to obtain several official positions despite his aristocratic background.

Because of the damage done to his estate in Lacoste, which was sacked in 1789 by an angry mob, he moved to Paris. In 1790, he was elected to the National Convention, where he represented the far left. He was a member of the Piques section, notorious for its radical views. He wrote several political pamphlets, in which he called for the implementation of direct vote. However, there is much to suggest that he suffered abuse from his fellow revolutionaries due to his aristocratic background. Matters were not helped by his son's May 1792 desertion from the military, where he had been serving as a second lieutenant and the aide-de-camp to an important colonel, the Marquis de Toulengeon. De Sade was forced to disavow his son's desertion in order to save himself. Later that year, his name was added – whether by error or wilful malice – to the list of émigrés of the Bouches-du-Rhône department.[17]

While claiming he was opposed to the Reign of Terror in 1793, he wrote an admiring eulogy for Jean-Paul Marat. At this stage, he was becoming publicly critical of Maximilien Robespierre and, on 5 December, he was removed from his posts, accused of "moderatism", and imprisoned for almost a year. He was released in 1794, after the overthrow and execution of Robespierre had effectively ended the Reign of Terror.

In 1796, now all but destitute, he had to sell his ruined castle in Lacoste.

Imprisonment for his writings and death

In 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the arrest of the anonymous author of Justine and Juliette.[8] De Sade was arrested at his publisher's office and imprisoned without trial; first in the Sainte-Pélagie Prison and, following allegations that he had tried to seduce young fellow prisoners there, in the harsh Bicêtre Asylum.

After intervention by his family, he was declared insane in 1803 and transferred once more to the asylum at Charenton. His ex-wife and children had agreed to pay his pension there. Constance was allowed to live with him at Charenton. The benign director of the institution, Abbé de Coulmier, allowed and encouraged him to stage several of his plays, with the inmates as actors, to be viewed by the Parisian public.[8] Coulmier's novel approaches to psychotherapy attracted much opposition. In 1809, new police orders put de Sade into solitary confinement and deprived him of pens and paper. In 1813, the government ordered Coulmier to suspend all theatrical performances.

De Sade began a sexual relationship with 14-year-old Madeleine LeClerc, daughter of an employee at Charenton. This affair lasted some 4 years, until his death in 1814.

He had left instructions in his will forbidding that his body be opened for any reason whatsoever, and that it remain untouched for 48 hours in the chamber in which he died, and then placed in a coffin and buried on his property located in Malmaison near Épernon. His skull was later removed from the grave for phrenological examination.[8] His son had all his remaining unpublished manuscripts burned, including the immense multi-volume work Les Journées de Florbelle.

Appraisal and criticism

Numerous writers and artists, especially those concerned with sexuality, have been both repelled and fascinated by de Sade.

The contemporary rival pornographer Rétif de la Bretonne published an Anti-Justine in 1798.

Geoffrey Gorer, an English anthropologist and author (1905–1985), wrote one of the earliest books on de Sade entitled The Revolutionary Ideas of the Marquis de Sade in 1935. He pointed out that de Sade was in complete opposition to contemporary philosophers for both his "complete and continual denial of the right to property" and for viewing the struggle in late 18th century French society as being not between "the Crown, the bourgeoisie, the aristocracy or the clergy, or sectional interests of any of these against one another", but rather all of these "more or less united against the proletariat." By holding these views, he cut himself off entirely from the revolutionary thinkers of his time to join those of the mid-nineteenth century. Thus, Gorer argued, "he can with some justice be called the first reasoned socialist."[18]

Simone de Beauvoir (in her essay Must we burn Sade?, published in Les Temps modernes, December 1951 and January 1952) and other writers have attempted to locate traces of a radical philosophy of freedom in de Sade's writings, preceding modern existentialism by some 150 years. He has also been seen as a precursor of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis in his focus on sexuality as a motive force. The surrealists admired him as one of their forerunners, and Guillaume Apollinaire famously called him "the freest spirit that has yet existed".[19]

Pierre Klossowski, in his 1947 book Sade Mon Prochain ("Sade My Neighbour"), analyzes de Sade's philosophy as a precursor of nihilism, negating Christian values and the materialism of the Enlightenment.

One of the essays in Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno's Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947) is titled "Juliette, or Enlightenment and Morality" and interprets the ruthless and calculating behavior of Juliette as the embodiment of the philosophy of enlightenment. Similarly, psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan posited in his 1966 essay "Kant avec de Sade" that de Sade's ethics was the complementary completion of the categorical imperative originally formulated by Immanuel Kant. However, at least one philosopher has rejected Adorno and Horkheimer’s claim that de Sade's moral skepticism is actually coherent, or that it reflects Enlightenment thought.[20][21]

In his 1988 Political Theory and Modernity, William E. Connolly analyzes Sade's Philosophy in the Bedroom as an argument against earlier political philosophers, notably Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Thomas Hobbes, and their attempts to reconcile nature, reason, and virtue as bases of ordered society. Similarly, Camille Paglia[22] argued that de Sade can be best understood as a satirist, responding "point by point" to Rousseau's claims that society inhibits and corrupts mankind's innate goodness: Paglia notes that Sade wrote in the aftermath of the French Revolution, when Rousseauist Jacobins instituted the bloody Reign of Terror and Rousseau's predictions were brutally disproved.

In The Sadeian Woman: And the Ideology of Pornography (1979), Angela Carter provides a feminist reading of Sade, seeing him as a "moral pornographer" who creates spaces for women. Similarly, Susan Sontag defended both Sade and Georges Bataille's Histoire de l'oeil (Story of the Eye) in her essay "The Pornographic Imagination" (1967) on the basis their works were transgressive texts, and argued that neither should be censored. By contrast, Andrea Dworkin saw Sade as the exemplary woman-hating pornographer, supporting her theory that pornography inevitably leads to violence against women. One chapter of her book Pornography: Men Possessing Women (1979) is devoted to an analysis of Sade. Susie Bright claims that Dworkin's first novel Ice and Fire, which is rife with violence and abuse, can be seen as a modern retelling of Sade's Juliette.[23]

Influence

Various influential cultural figures have expressed a great interest in de Sade's work, including the French philosopher Michel Foucault,[24] the American film maker John Waters[25] and the Spanish filmmaker Jesús Franco. The poet Algernon Charles Swinburne is also said to have been highly influenced by de Sade.[26] Nikos Nikolaidis' 1979 film The Wretches Are Still Singing was shot in a surreal way with a predilection for the aesthetics of the Marquis de Sade; de Sade is said to have influenced Romantic and Decadent authors such as Charles Baudelaire, Gustave Flaubert, Algernon Swinburne, and Rachilde; and to have influenced a growing popularity of nihilism in Western thought.[27]

The philosopher of egoist anarchism Max Stirner is also speculated to have been influenced by de Sade's work.[28]

Serial killer Ian Brady, who with Myra Hindley carried out torture and murder of children known as the Moors murders in England during the 1960s, was fascinated by de Sade, and the suggestion was made at their trial and appeals[29] that the tortures of the children (the screams and pleadings of whom they tape-recorded) were influenced by de Sade's ideas and fantasies. According to Donald Thomas, who has written a biography on de Sade, Brady and Hindley had read very little of de Sade's actual work; the only book of his they possessed was an anthology of excerpts that included none of his most extreme writings.[30] In the two suitcases found by the police that contained books that belonged to Brady was The Life and Ideas of the Marquis de Sade.[31] Hindley herself claimed that Brady would send her to obtain books by de Sade, and that after reading them he became sexually aroused and beat her.[32]

In Philosophy in the Bedroom de Sade proposed the use of induced abortion for social reasons and population control, marking the first time the subject had been discussed in public. It has been suggested that de Sade's writing influenced the subsequent medical and social acceptance of abortion in Western society.[33]

Cultural depictions

There have been many and varied references to the Marquis de Sade in popular culture, including fictional works and biographies. The eponym of the psychological and subcultural term sadism, his name is used variously to evoke sexual violence, licentiousness, and freedom of speech.[34] In modern culture his works are simultaneously viewed as masterful analyses of how power and economics work, and as erotica.[35] Sade's sexually explicit works were a medium for the articulation of the corrupt and hypocritical values of the elite in his society, which caused him to become imprisoned. He thus became a symbol of the artist's struggle with the censor. De Sade's use of pornographic devices to create provocative works that subvert the prevailing moral values of his time inspired many other artists in a variety of media. The cruelties depicted in his works gave rise to the concept of sadism. De Sade's works have to this day been kept alive by artists and intellectuals because they espouse a philosophy of extreme individualism that became reality in the economic liberalism of the following centuries.[36]

In the late 20th century, there was a resurgence of interest in de Sade; leading French intellectuals like Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, and Michel Foucault published studies of the philosopher, and interest in de Sade among scholars and artists continued.[34] In the realm of visual arts, many surrealist artists had interest in the Marquis. De Sade was celebrated in surrealist periodicals, and feted by figures such as Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Éluard, and Maurice Heine; Man Ray admired Sade because he and other surrealists viewed him as an ideal of freedom.[36] The first Manifesto of Surrealism (1924) announced that "Sade is surrealist in sadism", and extracts of the original draft of Justine were published in Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution.[37] In literature, de Sade is referenced in several stories by horror and science fiction writer (and author of Psycho) Robert Bloch, while Polish science fiction author Stanisław Lem wrote an essay analyzing the game theory arguments appearing in de Sade's Justine.[38] The writer Georges Bataille applied de Sade's methods of writing about sexual transgression to shock and provoke readers.[36]

De Sade's life and works have been the subject of numerous fictional plays, films, pornographic or erotic drawings, etchings, and more. These include Peter Weiss's play Marat/Sade, a fantasia extrapolating from the fact that de Sade directed plays performed by his fellow inmates at the Charenton asylum.[39] Yukio Mishima, Barry Yzereef, and Doug Wright also wrote plays about de Sade; Weiss's and Wright's plays have been made into films. His work is referenced on film at least as early as Luis Buñuel's L'Âge d'Or (1930), the final segment of which provides a coda to de Sade's 120 Days of Sodom, with the four debauched noblemen emerging from their mountain retreat. In 1969, American International Films released a German-made production called de Sade, with Keir Dullea in the title role. Pier Paolo Pasolini filmed Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), updating de Sade's novel to the brief Salò Republic; Benoît Jacquot's Sade and Philip Kaufman's Quills (from the play of the same name by Doug Wright) both hit cinemas in 2000. Quills, inspired by de Sade's imprisonment and battles with the censorship in his society,[36] portrays de Sade as a literary freedom fighter who is a martyr to the cause of free expression.[40]

Often de Sade himself has been depicted in American popular culture less as a revolutionary or even as a libertine and more akin to a sadistic, tyrannical villain. For example, in the final episode of the television series Friday the 13th: The Series, Micki, the female protagonist, travels back in time and ends up being imprisoned and tortured by de Sade. Similarly, in the horror film Waxwork, de Sade is among the film's wax villains to come alive.

Writing

Literary criticism

The Marquis de Sade viewed Gothic fiction as a genre that relied heavily on magic and phantasmagoria. In his literary criticism de Sade sought to prevent his fiction from being labeled "Gothic" by emphasizing Gothic's supernatural aspects as the fundamental difference from themes in his own work. But while he sought this separation he believed the Gothic played a necessary role in society and discussed its roots and its uses. He wrote that the Gothic novel was a perfectly natural, predictable consequence of the revolutionary sentiments in Europe. He theorized that the adversity of the period had rightfully caused Gothic writers to "look to hell for help in composing their alluring novels." Sade held the work of writers Matthew Lewis and Ann Radcliffe high above other Gothic authors, praising the brilliant imagination of Radcliffe and pointing to Lewis' The Monk as without question the genre’s best achievement. De Sade nevertheless believed that the genre was at odds with itself, arguing that the supernatural elements within Gothic fiction created an inescapable dilemma for both its author and its readers. He argued that an author in this genre was forced to choose between elaborate explanations of the supernatural or no explanations at all and that in either case the reader was unavoidably rendered incredulous. Despite his celebration of The Monk, de Sade believed that there was not a single Gothic novel that had been able to overcome these problems. He theorized that if these problems were successfully avoided within the genre that the resulting work would be universally regarded for its excellence in fiction.[41]

Many assume that de Sade's criticism of the Gothic novel is a reflection of his frustration with sweeping interpretations of works like Justine. Within his objections to the lack of verisimilitude in the Gothic may have been an attempt to present his own work as the better representation of the whole nature of man. Since de Sade professed that the ultimate goal of an author should be to deliver an accurate portrayal of man, it is believed that de Sade's attempts to separate himself from the Gothic novel highlights this conviction. For de Sade, his work was best suited for the accomplishment of this goal in part because he was not chained down by the supernatural silliness that dominated late 18th-century fiction.[42] Moreover, it is believed that de Sade praised The Monk (which displays Ambrosio’s sacrifice of his humanity to his unrelenting sexual appetite) as the best Gothic novel chiefly because its themes were the closest to those within his own work.[43]

Libertine novels

De Sade's fiction has been tagged under many different titles, including pornography, Gothic, and baroque. Sade’s most famous books are often classified not as Gothic but as libertine novels, and include the novels Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue; Juliette; The 120 Days of Sodom; and Philosophy in the Bedroom. These works challenge traditional perceptions of sexuality, religion, law, age, and gender. His opinions on sexual violence, sadomasochism, and pedophilia stunned even those contemporaries of de Sade who were quite familiar with the dark themes of the Gothic novel during its popularity in the late 18th century. Suffering is the primary rule, as in these novels one must often decide between sympathizing with the torturer or the victim. While these works focus on the dark side of human nature, the magic and phantasmagoria that dominates the Gothic is noticeably absent and is the primary reason these works are not considered to fit the genre.[44]

Through the unreleased passions of his libertines, de Sade wished to shake the world at its core. With 120 Days, for example, de Sade wished to present "the most impure tale that has ever been written since the world exists."[45] Despite his literary attempts at evil, his characters and stories often fell into repetitive depictions of sodomy and sexual violence. Simone de Beauvoir and Georges Bataille have argued that the repetitive form of his libertine novels, though it hindered the artfulness of his prose, ultimately strengthened his individualist arguments.[46] [47]

Short fiction

Subtitled "Heroic and Tragic Tales", Sade combines romance and horror, employing several Gothic tropes for dramatic purposes. There is blood, banditti, corpses and, of course, insatiable lust. Compared to works like Justine, here Sade is relatively tame, as overt eroticism and torture is subtracted for a more psychological approach. It is the impact of sadism instead of acts of sadism itself that emerge in this work, unlike the aggressive and rapacious approach in his libertine works.[43] The modern volume entitled Gothic Tales collects a variety of other short works of fiction intended to be included in Sade's Contes et Fabliaux d'un Troubadour Provencal du XVIII Siecle.

An example is "Eugénie de Franval", a tale of incest and retribution. In its portrayal of conventional moralities it is somewhat of a departure from the erotic cruelties and moral ironies that dominate his libertine works. It opens with a domesticated approach:

"To enlighten mankind and improve its morals is the only lesson which we offer in this story. In reading it, may the world discover how great is the peril which follows the footsteps of those who will stop at nothing to satisfy their desires."

Descriptions in Justine seem to anticipate Radcliffe's scenery in The Mysteries of Udolpho and the vaults in The Italian, but, unlike these stories, there is no escape for Sade's virtuous heroine, Justine. Unlike the milder Gothic fiction of Radcliffe, Sade's horror ends in sodomy, rape, or torture. To have a character like Justine, who is stripped without ceremony and bound to a wheel for fondling and thrashing, would be unthinkable in the domestic Gothic fiction written for the bourgeoisie. Sade even contrives a kind of affection between Justine and her tormentors, suggesting shades of masochism in his heroine.[48]

Sadism in the Gothic novel

Despite the strong adverse reaction to de Sade's work and de Sade's own disassociation from the Gothic novel, the similarities between the fiction of sadism and the Gothic novel were much closer than many of its readers or providers even realized. After the controversy surrounding Matthew Lewis' The Monk, Minerva Press released The New Monk as a supposed indictment of a wholly immoral book. It features the sadistic Mrs. Rod, whose boarding school for young women becomes a torture chamber equipped with its own "flogging-room". Ironically, The New Monk wound up increasing the level of cruelty, but as a parody of the genre, it illuminates the link between sadism and the Gothic novel.[48]

In popular culture

- In Garth Ennis's Preacher comic series, a pale, long-haired character by the name of Jesus de Sade is intended as an insult to Christians and a parody of Marquis de Sade by having him sodomizing small animals and his pantless butlers

- The Marquis de Sade appears as a character in the Grant Morrison's graphic novel The Invisibles.

- "Howard Roark is the Marquis de Sade of architecture." In the Ayn Rand novel Fountainhead (1943).

- The Guy Endore novel Satan's Saint (1965) is a fictionalized biography of Marquis de Sade.

- The Marquis de Sade is mentioned in the lyrics of The Stone Roses song "Fools Gold".

- The 1990 song "sadeness (Part I)" by the group Enigma was inspired by the Marquis de Sade.

- The 2000 film Quills is a heavily fictionalized account of the Marquis de Sade's imprisonment. It starred Geoffrey Rush as de Sade.

- The Marquis de Sade appears in the 2011 novel "Madame Tussaud," by Michelle Moran.

- The Marquis de Sade appears as an non-player character in the 2014 video game Assassin's Creed: Unity.

- The Marquis de Sade appears as an boss in the classic horror MMORPG, DarkEden in the dungeon, "Castle Lacoste".

- The character of Orin in the 1986 movie musical Little Shop of Horrors is referred to as the Marquis de Sade during the "Dentist!" song number.

- Marquis (1989), a film by Henri Xhonneux and Roland Topor, was inspired by Sade's imprisonment. The characters wear masques of anthopomorphic animals.

- The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade is a play by Peter Weisse that depicts the Marquis.

Bibliography

See also

- BDSM

- Fetish fashion

- Leopold von Sacher-Masoch

- Sadomasochism

- Sexual fetishism

- Sexual sadism disorder

- Quills

References

- 1 2 3 "The Eponymous Sadist". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2016-04-26.

- 1 2 3 4 "Biography.com".

- 1 2 3 4 Hayman, Ronald. Marquis de Sade: The Genius of Passion.

- ↑ Love, Brenda (2002). The Encyclopedia of Unusual Sex Practices. UK: Abacus. p. 145. ISBN 0-349-11535-4.

- ↑ Vie du Marquis de Sade by Gilbert Lêly, 1961

- ↑ du Plessix Gray, Francine At Home With The Marquis de Sade: A Life, Simon and Schuster 1998, p420

- ↑ du Plessix Gray, Francine At Home With The Marquis de Sade: A Life, Simon and Schuster 1998, p418

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Perrottet, Tony (February 2015). "Who Was the Marquis de Sade?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ↑ Marianne2: Quand le marquis de Sade entre dans l'ère du marketing by Jean-Pierre de Lucovich, Monday 30 July 2001. http://m.marianne2.fr/index.php?action=article&numero=139612

- ↑ http://www.chateaudeconde.com/histrad2.htm

- ↑ Neil Schaeffer, The Marquis de Sade: a Life (Knopf, 1999)

- ↑ Timeline of de Sade's life by Neil Schaeffer. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ↑ Barthes, Roland (2004) [1971]. Life of Sade. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

- ↑ Kathleen Barry, "Female Sexual Slavery", p.220

- ↑ Mirabeau, Honoré-Gabriel Riqueti; Guillaume Apollinaire; P. Pierrugues (1921). L'Œuvre du comte de Mirabeau. Paris, France: Bibliothèque des curieux. p. 9.

- ↑ McLemee, Scott (2002). "Sade, Marquis de". glbtq.com.

- ↑ "The Life and Times of the Marquis de Sade". Geocities.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- ↑ Gorer, Geoffrey. The Revolutionary Ideas of the Marquis de Sade, p. 197.

- ↑ Queenan, Joe (2004). Malcontents. Philadelphia: Running Press. p. 519. ISBN 0-7624-1697-1.

- ↑ Geoffrey Roche, "Much Sense the Starkest Madness: de Sade’s Moral Scepticism." Angelaki Volume 15, Issue 1 April 2010, pages 45 – 59. Retrieved 12 December 2010. .

- ↑ Geoffrey Roche, "An Unblinking Gaze: On the Philosophy of the Marquis de Sade." PhD thesis, University of Auckland, 2004. Retrieved 2 June 2013. .

- ↑ Paglia, Camille. (1990) Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson. NY: Vintage, ISBN 0-679-73579-8, Chapter 8, "Return of the Great Mother: Rousseau vs. Sade".

- ↑ Andrea Dworkin has Died, from Susie Bright's Journal, 11 April 2005. Retrieved 23 November 2006

- ↑ Eribon, Didier (1991) [1989]. Michel Foucault. Betsy Wing (translator). Cambridge, MAS.: Harvard University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0674572866.

- ↑ Waters, John (2005) [1981]. Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste. Philadelphia: Running Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-1560256984.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jerry (1965). "Swinburne - The Disappointed Protagonist". Yale French Studies. Yale University Press. No.35: 81–88. JSTOR 2929455.

- ↑ https://home.isi.org/dostoevsky-vs-marquis-de-sade Dostoevsky vs the Marquis de Sade

- ↑ http://prosper.cofc.edu/~desade/B6.%20Maurice%20Schuhmann.%20Le%20successeur....pdf Max Stirner - The Successor of the Marquis de Sade, Maurice Schuhmann

- ↑ Hindley,, Myra. "Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Retrieved 5 July 2009. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Donald Thomas, The Marquis de Sade (Allison & Busby 1992)

- ↑ Duncan Staff, The Lost Boy, p.156

- ↑ Boggan, Steve (15 August 1998). "The Myra Hindley Case: `Brady told me that I would be in a grave too if I backed out'". The Independent. London.

- ↑ A D Farr (1980). "The Marquis de Sade and induced abortion". Journal of Medical Ethics. 6: 7–10. doi:10.1136/jme.6.1.7.

- 1 2 Phillips, John, 2005, The Marquis De Sade: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280469-3.

- ↑ Guins, Raiford, and Cruz, Omayra Zaragoza, 2005, Popular Culture: A Reader, Sage Publications, ISBN 0-7619-7472-5.

- 1 2 3 4 MacNair, Brian, 2002, Striptease Culture: Sex, Media and the Democratization of Desire, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-23733-5.

- ↑ Bate, David, 2004, Photography and Surrealism: Sexuality, Colonialism and Social Dissent, I.B. Tauris, ISBN 1-86064-379-5.

- ↑ Istvan Csicsery-Ronay, Jr. (1986). "Twenty-Two Answers and Two Postscripts: An Interview with Stanislaw Lem". DePauw University.

- ↑ Dancyger, Ken, 2002, The Technique of Film and Video Editing: History, Theory, and Practice, Focal Press, ISBN 0-240-80225-X.

- ↑ Raengo, Alessandra, and Stam, Robert, 2005, Literature and Film: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Film Adaptation, Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-23055-6.

- ↑ Sade, Marquis de (2005). "An Essay on Novels". The Crimes of Love. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953998-7.

- ↑ Gorer, Geoffrey (1962). The Life and Ideas of the Marquis de Sade. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1 2 "Introduction". The Crimes of Love. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-953998-7.

- ↑ Phillips, John (2001). Sade: The Libertine Novels. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 0-7453-1598-4.

- ↑ Gray, Francine du Plessix (1998). At Home with the Marquis de Sade: A Life. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80007-1.

- ↑ de Beauvoir, Simone (1953). Must We Burn Sade?. Peter Nevill.

- ↑ Bataille, Georges (1985). Literature and Evil. London: Marion Boyars Publishers Inc. ISBN 0-7145-0346-0.

- 1 2 Thomas, Donald (1992). The Marquis de Sade. London: Allison & Busby.

Further reading

- Sade's Sensibilities. (2014) edited by Kate Parker and Norbert Sclippa (A collection of essays reflecting on Sade's influence on his bicentennial anniversary.)

- Forbidden Knowledge: From Prometheus to Pornography. (1994) by Roger Shattuck (Provides a sound philosophical introduction to Sade and his writings.)

- Pour Sade. (2006) by Norbert Sclippa

- Marquis de Sade: his life and works. (1899) by Iwan Bloch

- Sade Mon Prochain. (1947) by Pierre Klossowski

- Lautréamont and Sade. (1949) by Maurice Blanchot

- The Marquis de Sade, a biography. (1961) by Gilbert Lély

- Philosopher of Evil: The Life and Works of the Marquis de Sade. (1962) by Walter Drummond

- The life and ideas of the Marquis de Sade. (1963) by Geoffrey Gorer

- Sade, Fourier, Loyola. (1971) by Roland Barthes

- De Sade: A Critical Biography. (1978) by Ronald Hayman

- The Sadeian Woman: An Exercise in Cultural History. (1979) by Angela Carter

- The Marquis de Sade: the man, his works, and his critics: an annotated bibliography. (1986) by Colette Verger Michael

- Sade, his ethics and rhetoric. (1989) collection of essays, edited by Colette Verger Michael

- Marquis de Sade: A Biography. (1991) by Maurice Lever

- The philosophy of the Marquis de Sade. (1995) by Timo Airaksinen

- Dark Eros: The Imagination of Sadism. (1996) by Thomas Moore (spiritual writer)

- Sade contre l'Être suprême. (1996) by Philippe Sollers

- A Fall from Grace (1998) by Chris Barron

- Sade: A Biographical Essay (1998) by Laurence Louis Bongie

- An Erotic Beyond: Sade. (1998) by Octavio Paz

- The Marquis de Sade: a life. (1999) by Neil Schaeffer

- At Home With the Marquis de Sade: A Life. (1999) by Francine du Plessix Gray

- Sade: A Sudden Abyss. (2001) by Annie Le Brun

- Sade: from materialism to pornography. (2002) by Caroline Warman

- Marquis de Sade: the genius of passion. (2003) by Ronald Hayman

- Marquis de Sade: A Very Short Introduction (2005) by John Phillips

- The Dangerous Memoir of Citizen Sade (2000) by A. C. H. Smith (A biographical novel)

- Outsider Biographies; Savage, de Sade, Wainewright, Ned Kelly, Billy the Kid, Rimbaud and Genet: Base Crime and High Art in Biography and Bio-Fiction, 1744-2000 (2014) by Ian H. Magedera

External links

- Marquis de Sade at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Works by Marquis de Sade at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Marquis de Sade at Internet Archive

- Works by Marquis de Sade at Open Library

- Norbert Sclippa

- Œuvres du Marquis de Sade

- Marquis de Sade at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Marquis de Sade at the Internet Movie Database

- Biography at Trivia Library

- Carnet du Marquis de Sade Site run by a descendant of the Marquis de Sade. Weekly publication of the article(s) around the current de Sade.

- Crime Library: The Marquis de Sade

- McLemee, Scott. "Sade, Marquis de (1740-1814)". glbtq.com. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

.png)