Michigan Central Station

|

Michigan Central Station | |

|

Michigan Central Station | |

| |

| Location |

2405 West Vernor Highway Detroit, Michigan |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°19′43.69″N 083°04′39.83″W / 42.3288028°N 83.0777306°WCoordinates: 42°19′43.69″N 083°04′39.83″W / 42.3288028°N 83.0777306°W |

| Area | 500,000 sq ft (46,000 m2) |

| Built | June 1912 – December 1913 |

| Architect |

Reed and Stem, Warren and Wetmore |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts |

| NRHP Reference # | 75000969 |

| Added to NRHP | April 16, 1975 |

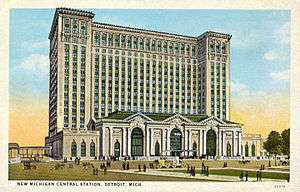

Michigan Central Station (also known as Michigan Central Depot or MCS) was the main intercity passenger rail depot for Detroit, Michigan. Built for the Michigan Central Railroad, it replaced the original depot in downtown Detroit, which was shuttered after a major fire on December 26, 1913, forcing the still unfinished station into early service. Formally dedicated on January 4, 1914, the station remained open for business until the cessation of Amtrak service on January 6, 1988. At the time of its construction, it was the tallest rail station in the world.[1]

The building is located in the Corktown district of Detroit near the Ambassador Bridge, approximately ¾-mile (1.2 km) southwest of downtown Detroit. It is located behind Roosevelt Park, and the Roosevelt Warehouse is adjacent to the east. The city's Roosevelt Park serves as a grand entryway to the station. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.

Restoration projects and plans have gone as far as the negotiation process, but none has come to fruition. Since 2011, demolition works, minor structural repairs, repairs of the roof structure, and covering the glass roof openings in the concourse have been performed. The basement, which was once full of water, has been fully drained, and a barbed wire fence has been installed in an attempt to keep out vandals.

Images of the building remain a premier example of ruins photography.[2]

History

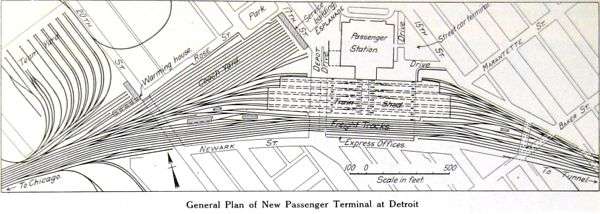

The building began operating as Detroit's main passenger depot in 1913 after the older Michigan Central Station burned on December 26, 1913. It was originally owned and operated by Michigan Central Railroad. It was planned as part of a large project that included the Michigan Central Railway Tunnel below the Detroit River for freight and passengers. The old station was located on a spur line, which was inconvenient for the high volume of passengers it served. The new Michigan Central placed passenger service on the main line.

The growing trend toward increased automobile use was not a large concern in 1912, as is evident in the design of the building. Most passengers would arrive at and leave from Michigan Central Station by interurban service or streetcar, due to the station's distance from downtown Detroit. The station was placed away from downtown in order to stimulate related development to come in its direction. An ambitious project to connect the station to the Cultural Center via a wide boulevard was never realized.[3]

At the beginning of World War I, the peak of rail travel in the United States, more than 200 trains left the station each day and lines would stretch from the boarding gates to the main entrance. In the 1940s, more than 4,000 passengers a day used the station and more than 3,000 people worked in its office tower. Among notable passengers arriving at MCS were Presidents Herbert Hoover, Harry S. Truman and Franklin D. Roosevelt, actor Charlie Chaplin and inventor Thomas Edison.

In the 1920s Henry Ford began to buy land near the station and made construction plans, but the Great Depression and other circumstances squelched this and many other development efforts. The original design included no large parking facility. When the interurban service was discontinued less than two decades after MCS opened, the station was effectively isolated from the large majority of the population who drove cars and needed parking to use the facility.

Passenger volume did not decrease immediately. During World War II, the station was used heavily by military troops. After the war, with a growth in automobile ownership, people used trains less frequently for vacation or other travel. Service was cut back and passenger traffic became so low that the owners of the station attempted to sell the facility in 1956 for US$5 million, one-third of its original 1913 building cost. Another attempted sale in 1963 failed for lack of buyers. In 1967, maintenance costs were seen as too high relative to the decreasing passenger volume. The restaurant, arcade shops, and main entrance were closed, along with much of the main waiting room. This left only two ticket windows to serve passengers and visitors, who used the same parking-lot entrance as railroad employees working in the building.

Amtrak took over the nation's passenger rail service in 1971, reopening the main waiting room and entrance in 1975. It started a $1.25 million renovation project in 1978. Six years later, the building was sold for a transportation center project that never materialized. On January 6, 1988, the last Amtrak train pulled away from the station after owners decided to close the facility. In July 1992, the Detroit Master Plan of Policies for the southwest sector's urban design identified the station as an attractive or interesting feature to be recognized, enhanced and promoted.[4] Amtrak service continued at a platform near the building until a new station opened several miles away in New Center in 1994.[5]

Controlled Terminals Inc. acquired the station in 1996. Its sister company, the Detroit International Bridge Co., owns the nearby Ambassador Bridge and both are part of a group of transportation-related companies owned by businessman Manuel Moroun, Chairman and CEO of CenTra Inc.[6][7] The company demolished the train shed in 2000, and converted the remaining tracks and platforms into an intermodal freight facility, named "Expressway" and operated by Canadian Pacific Railway. This facility was closed in June 2004.[8]

Although the City of Detroit considered the building a "Priority Cultural Site" in 2006,[9] the City Council on April 7, 2009 passed a resolution to demolish the Depot.[10] Seven days later, Detroit resident Stanley Christmas sued the city of Detroit to stop the demolition effort, citing the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966.[11]

In June 2011 work began on partial asbestos abatement on the first floor; other work conducted included interior demolition work, removal of broken glass from first floor windows, and removal of water.[12] As of June 2012, electricity has been restored to the interior. Lights have illuminated the main lobby nightly, The website Talk To The Station has been launched by the Michigan Central Station Preservation Society to provide a sounding board for community questions and suggestions.

On June 10, 2014, it was reported that the owners of Michigan Central Station were moving forward with about $676,000 in rehab work, and had received permits to install a new 9,000-pound capacity freight elevator, which will allow for the smooth installation of new windows and roof work.[13] In late 2014 work to install the elevator started, with an expected completion by February.[14]

In February 2015 the owners announced that they would be replacing more than 1,000 windows above the first level. In late April the city announced a land swap deal with the Bridge Company to transfer a 3-acre strip of Riverside Park near the Ambassador Bridge for 4.8 acres of adjacent property owned by the Bridge Company. As part of that agreement, the city would receive up to $5 million for park improvements, and the Bridge Company agreed to replace the windows in the train station.[15] In July the Detroit City Council approved the land transfer.[16] As of December 2015, all of the new windows have been installed.[17] Despite this work, the future of the building is undetermined.

Architecture

The building is of the Beaux-Arts Classical style of architecture, designed by the Warren & Wetmore and Reed and Stem firms who also designed New York City's Grand Central Terminal.[3][18] Michigan Central was designed at the same time, and is seen as a spiritual twin to Grand Central in New York, as both were meant as flagship stations on Vanderbilt's rail lines, as well as the fact that both were designed to have office towers in their original design concepts (Grand Central's tower was not built until the MetLife Tower was built in the 1960s), and both have the same detailing, and were opened six months apart. The price tag for this 500,000-square-foot (46,000 m2) building was $15 million when it was built. Roosevelt Park creates a grand entryway for the station, which was fully realized around 1920.

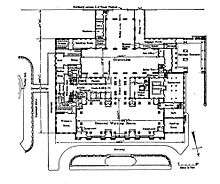

The building is composed of two distinct parts: the train station and the 18-story office tower. The roof height is 230 feet (70 m). The original plan for the tower included a hotel, offices for the rail company, or a combination of both. The tower was used only for office space by the Michigan Central Railroad and subsequent owners of the building. The tower was never completely used; the top floors were never completely furnished, and served no function.

The main waiting room on the main floor was modeled after an ancient Roman bathhouse, with walls of marble and vaulted ceilings.[3] The building also housed a large hall adorned with Doric columns that housed the ticket office and arcade shops. Beyond the arcade was the concourse, which had brick walls and a large copper skylight. From here, passengers would walk down a ramp to a tunnel from which the platforms could be accessed by stairs and elevators. Under the shed there were ten passenger platforms consisting of one side platform and five island platforms along ten paired tracks. In addition, one track served the Railway Express Agency (REA) mail service at the southern end of the shed. Immediately outside the shed were seven additional freight tracks.[19] Below the tracks and building was a large area for baggage and mail handling and offices.

Future development

In 2008, the station owners said that their goal was to renovate the decaying building, which had closed in 1988. The estimated cost of renovations was $80 million, but the owners viewed finding the right use as a greater problem than financing.[20] On March 25, 2011, in an effort to push forward a potential sale and redevelopment, Dan Stamper, spokesperson for Ambassador Bridge owner Manuel "Matty" Moroun, announced plans to work with the City of Detroit on funding replacement of the tower's roof, and installing new windows on the structure. Stamper told the Detroit News: "It would be much easier to help a developer to come up with a package to use the depot if some improvements were made."[21]

Proposals and concepts for redevelopment in the past have included these potential uses:

- Trade Processing Center – Adapting the station as a customs and international trade processing center due to its proximity to the Ambassador Bridge.[22]

- Convention Center and Casino – Owner Moroun proposed that Michigan Central Station be restored as the centerpiece of a new convention center, possibly combined with a casino.[6] Such a project could cost $1.2 billion, including $300 million to restore the station. Dan Stamper, president of Detroit International Bridge, noted that the station should have been used as one of the city's casinos.[20]

- Detroit Police Headquarters – In 2004, Detroit mayor Kwame Kilpatrick announced that the city was pursuing options to relocate its police department headquarters and possibly consolidate other law enforcement offices to MCS. However, in mid-2005, the city canceled the plan and chose to renovate its existing headquarters.[22]

- Michigan State Police Headquarters – In 2010, State Senator Cameron S. Brown and Mickey Bashfield, a government relations official for the building owner CenTra Inc., suggested that the station could become the Detroit headquarters of the Michigan State Police, include some United States Department of Homeland Security offices, and serve as a center for trade inspections.[23]

Renovation estimates have ranged from $80 to $300 million. The Detroit Wayne County Port Authority has the ability to issue bonds and could take part in financing.

The U.S. Department of Transportation has awarded $244 million in grants for high-speed rail upgrades between Chicago and Detroit.[24] A consortium of investors, including the Canadian Pacific Railway, has proposed a new, larger rail tunnel capable of handling large double-stacked freight cars under the Detroit River, which could open in 2017.[25][26] With the new tunnel emerging near the Michigan Central Station, a redeveloped station could function as a trade inspection facility.[23]

On May 5, 2011, the Detroit International Bridge Company announced it engaged the Ann Arbor firm of Quinn Evans on behalf of the Moroun family that owns the building to oversee restoration of the roof and windows of the structure. Bridge Company owner Moroun stated, "We hope this is just the beginning of a renaissance for the depot."[27] As of December 2015, all of the once broken windows have been replaced.[28] The once flooded basement has largely been drained, with about 4 inches of water at its highest still remaining in a sub-basement of the building. Structural Analysis of the building, as well as proposals for reuse of the building were going on as of early July 2016.

As of August 2016, the Moroun family has spent 10 years and $12 million on electricity, windows and the elevator shaft, to revitalize the building. Matthew Moroun said he might put part of his family's operations in the 18-story Corktown building.

In Popular Culture

The station has been featured in several films.[20] MCS was used for scenes in the movie Transformers (directed by Michael Bay) in October 2006. In January 2005, it was used as a location set for the movie The Island (also directed by Michael Bay). In September 2002, extensive closeups and fly-by shots were featured in the movie Naqoyqatsi. The 2005 film Four Brothers opens with the main character driving his car along the front of Michigan Central Station toward Michigan Avenue. The building has been used in some of Eminem's work, including the title sequence of the movie 8 Mile and his music video for the song "Beautiful", during the beginning of which the building features prominently. A scene from the ABC crime drama Detroit 1-8-7 was shot and set inside the station. The building's lobby was significant in the closing scenes of the 2012 documentary Detropia.[29]It was also used in a climactic fight scene in the 2016 movie Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice.

See also

References

- ↑ Kavanaugh, Kelli B. (2001). Detroit's Michigan Central Station (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-1881-6.

- ↑ Leary, John Patrick (15 January 2011). "Detroitism". Guernica. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

The station is the Eiffel Tower of ruin photography... as shown by the hobbyist and professional photographers who descend upon it on every sunny day.

- 1 2 3 Hill, Eric J. & John Gallagher (2002). AIA Detroit: The American Institute of Architects Guide to Detroit Architecture. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3120-3. P. 220.

- ↑ "Southwest Sector Policies, Article 309, POLICY 309-7" (PDF). City of Detroit. July 1002. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ Amtrak (1 May 1994). "National Timetable Spring/Summer 1994". Retrieved 2011-11-05.

- 1 2 Stephanie Fitch & Joann Muller (15 November 2004). "The Troll Under the Bridge". Forbes. Forbes.com. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ S Voyles (May–June 2009). "The Man Behind the Bridge – Matty Moroun Talks about Detroit, Business and Being Sentimental". Corp!. CorpMagazine.com. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ "Detroit Intermodal Freight Terminal Summary" (PDF). Michigan.gov. State of Michigan. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ "Non-motorized Urban Transportation Master Plan" (PDF). City of Detroit. June 2006. p. 20. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ WDIV-Detroit (7 April 2009). "City Council Votes To Demolish Depot". ClickonDetroit.com. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ WDIV-Detroit (8 April 2009). "Lawsuit Filed In Train Depot's Future". ClickonDetroit.com. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ "Moroun family making progress on Michigan Central Station rehabilitation". MLive. August 25, 2011.

- ↑ Muller, David (June 10, 2014). "Permits pulled for $676,000 in work on Michigan Central Station". Mlive.com. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ↑ Thibodeau, Ian (December 22, 2014). "Service elevator to be installed in Michigan Central Station by early 2015". MLive.

- ↑ Guillen, Joe (April 29, 2015). "Riverside Park, depot to get face-lifts in land swap". Detroit Free Press.

- ↑ Aguilar, Louis (July 28, 2015). "Detroit council approves Riverside Park deal". The Detroit News.

- ↑ Gallagher, John (August 13, 2015). "Train depot progress report: About 60% new windows". Detroit Free Press.

- ↑ Sharoff, Robert (2005). American City: Detroit Architecture, 1845-2005. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3270-6. P. 28.

- ↑ John A., Droege (1916). Passenger Terminal and Trains. New York City: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. p. 82.

- 1 2 3 Louis Aguilar (8 April 2008). "Michigan Central Depot owners say 'Roll 'em!". The Detroit News. Detnews.com. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- ↑ Tom Greenwood (25 March 2011). "Decaying Central Depot to get spruce-up". The Detroit News. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- 1 2 Ann Mullen (6 August 2006). "On Track". Metro Times. MetroTimes.com. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- 1 2 "New York Times asks: What's to be done with Michigan Central Station?". Model D. 9 March 2010.

- ↑ Nathan Bomey (28 January 2010). "High-speed rail grants include $244 million for Detroit-to-Chicago Amtrak improvements". Ann Arbor News. annarbor.com. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ Shea, Bill (17 June 2010). "Windsor Port Authority joins group seeking to build $400 million rail tunnel". Crain's Detroit Business. CrainsDetroit.com. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ↑ Shea, Bill (26 November 2013). "Detroit River rail tunnel to start construction next year, project leaders say". Crain's Detroit Business. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ John Gallagher (5 May 2011). "Bridge Company moves ahead with Michigan Central Depot restoration". Detroit Free Press. freep.com. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ↑ Thibodeau, Ian (4 February 2016). "Windows at Michigan Central Station completed on time and budget". M Live. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ J.R. Jones. "Detropia". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2013-11-02.

Further reading

- Kavanaugh, Kelli B. (2001). Detroit's Michigan Central Station (Images of America). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0738518817.

- Meyer, Katherine Mattingly; Martin C.P. McElroy with introduction by W. Hawkins Ferry, Hon A.I.A. (1980). Detroit Architecture A.I.A. Guide Revised Edition. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0814316511.

- Sobocinski, Melanie Grunow (2005). Detroit and Rome: building on the past. Regents of the University of Michigan. ISBN 978-0933691094.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Michigan Central Station. |

- Video Drone footage of Michigan Central Station taken January 2016.

- Video Drone footage of Michigan Central Station taken August 2014.

- Gallery of historical photographs at TalkToTheStation website

- Michigan Central Station at Emporis

- Michigan Central Station at SkyScraperPage

- Save Michigan Central Latest conservation effort and the official home of the Michigan Central Station Preservation Society.

- Michigan Central Station at Detroiturbex.com

| Former Services | ||||

| Preceding station | New York Central Railroad | Following station | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

toward Chicago | Michigan Central Railroad Main Line | Terminus | ||

| Terminus | Canada Southern Railway Main Line | Windsor toward Buffalo |

||

Wyandotte toward Toledo | Detroit Branch | Terminus | ||

Woodward Avenue toward Mackinaw City | Mackinaw City – Detroit | |||

| Preceding station | Following station | |||

toward Chicago | Twilight Limited | Terminus | ||

toward Chicago | Wolverine | Terminus | ||

toward Chicago | Lake Cities | toward Pontiac, MI |

||