Neil Harvey with the Australian cricket team in England in 1948

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Robert Neil Harvey | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

October 8, 1928 Fitzroy, Victoria, Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | Ninna | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.71 m (5 ft 7 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Batting style | Left-hand | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling style | Right-arm off-spin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Middle-order batsman | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International matches on tour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Test debut | 22 July 1948 v England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Test | 14 August 1948 v England | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tour statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: CricketArchive, 25 Mar. 2014 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Neil Harvey was a member of Donald Bradman's famous Australian cricket team, which toured England in 1948 and was undefeated in their 34 matches. This unprecedented feat by a Test side touring England earned them the sobriquet The Invincibles.

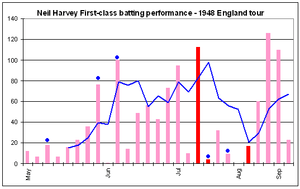

Aged 19, Harvey was the youngest player of the touring party. An attacking left-handed middle-order batsman, he had become the youngest Australian to score a Test century by compiling 153 in the Fifth Test against India in the preceding Australian summer of 1947–48. However, Harvey struggled early on in the tour, having difficulty adapting to English conditions. After being omitted from the first-choice team in the first half of the tour, Harvey's performances improved with his increasing familiarity with local conditions and he was called into the team for the Fourth Test at Headingley after an injury to Sid Barnes. Harvey scored 112 in a first innings counter-attack to keep Australia in contention after they had suffered a top-order collapse. Harvey hit the winning boundary in the second innings as Australia won the match with a Test world record successful run-chase of 3/404. He retained his place for the Fifth Test, ending the series with 133 runs at a batting average of 66.50.

Overall, Harvey ended with 1,129 runs at 53.76 in the first-class matches with four centuries, placing him sixth on the run-scoring aggregates and seventh in the batting averages for Australia. Harvey was an acrobatic fielder, regarded as the best in the Australian team. He was twelfth man in the Tests before he broke into the playing XI, and took several acclaimed catches throughout the tour, finishing with 17 catches as well as a solitary wicket with his occasional off spin.

Background

A somewhat diminutive left-handed middle-order batsman who was the second-youngest of six cricketing brothers, Harvey made his debut in first-class cricket for his state, Victoria, during the 1946–47 Australian season. The following year, at the age of 19, Harvey made his national debut in the Fourth Test against India in Australia in 1947–48 after a series of impressive performances at domestic level. In the Fifth Test at the Melbourne Cricket Ground, he hit 153 to break Archie Jackson's record for the youngest Australian to make a Test century.[1] The innings ensured him a place on the 1948 Invincibles tour of England as the youngest member of the 17-man squad. He was more than six and a half years younger than the next youngest players of the team, Arthur Morris and Bill Johnston.[2] Speaking about Harvey's selection, his captain (and one of three team selectors), Donald Bradman, opined: "He has the brilliance and daring of youth, and the likelihood of rapid improvement".[3]

Early tour

Australia traditionally fielded its first-choice team in the tour opener, which was customarily against Worcestershire.[4] Despite scoring a century in Australia's most recent Test, Harvey was made 12th man and it appeared that he was not initially in Bradman's Test plans. Australia promptly crushed the hosts by an innings.[5][6][7][8]

Harvey made his debut on English soil in the second tour match against Leicestershire. Batting at No. 5, he came in at 3/316 and made 12,[9] struggling against the local spinners,[10] as Australia collapsed to end on 448 before winning by an innings.[9] Harvey played a key role in Australia's victory in the next match against Yorkshire in Bradford, on a damp pitch that suited slower bowling.[5][11] Harvey took two catches in the home side's first innings of 71. He made seven in the first innings as Australia replied with 101.[12] After the hosts were bowled out for 89 in their second innings, Australia collapsed to 4/20 in pursuit of 60 for victory. No sooner had Harvey walked out to bat at No. 6, stand-in captain Lindsay Hassett—Bradman rested himself for the match—top-edged a pull shot and was caught to leave Australia at 5/20. To make matters worse, Sam Loxton was injured and could not bat, so Australia were effectively six wickets down and faced their first loss to an English county since 1912.[13] Harvey had scored a solitary run when he hit a ball to Len Hutton at short leg, who dived forwards and grabbed it with both hands before dropping it. Harvey then swept the next ball for a boundary.[12][13] Colin McCool was out at 6/31 before Harvey and wicket-keeper Don Tallon steadied Australia. Harvey was reprieved on 12; he took several steps down the pitch to the bowling of Frank Smailes and missed, but the wicketkeeper fumbled the stumping opportunity. Harvey then hit the winning runs by lifting Smailes for a six over the sightscreen, ending unbeaten on 18 not out.[12][14]

The Australians travelled to London to play Surrey at The Oval. Harvey scored seven and struggled in contrast to the rest of the Australians, who prospered to total 632, laying the foundation for an innings victory. Harvey took three catches in the match,[15] including two leaping catches in the second innings with his hands above his head. His feats prompted the local spectators to say that such acrobatic catches had never been seen at The Oval.[16] The home team's captain Stuart Surridge lofted a drive down the ground, and Harvey ran 25 m from wide long-on and leapt in the air to catch the ball, which would have cleared the boundary.[17] Harvey managed only 16 before being run out while batting with Bill Brown as Australia piled on 4/414 declared and defeated Cambridge University by an innings in the following match.[5][18]

Harvey was then rested as Australia crushed Essex by an innings and 451 runs, its largest winning margin for the summer.[5][6] During this match, the other batsmen set a world record for the most first-class runs scored in one day’s play, adding 721 on the opening day.[19] Harvey returned for the innings victory against Oxford University,[5][6] but scored only 23 as Australia amassed 431 in their only opportunity at the batting crease.[20]

The next match was against the Marylebone Cricket Club at Lord's. The MCC fielded seven players who would represent England in the Tests,[21][22][23][24][25][26] and were basically a full strength Test team, while Australia fielded their first-choice team. It was a chance to gain a psychological advantage, and given Harvey's early struggles in English conditions and his failure to pass 25 in his first six innings,[3] he was overlooked as Australia amassed 552 and won by an innings.[5][6]

After asking Bradman about the reason for his difficulties with the bat, Harvey was told that these were caused by rash shot selection and a tendency to hit the ball in the air. Bradman said "He was technically perfect in his shot production. He was batting well enough and simply getting out early."[3] Harvey adapted his style and improved his performance. In the next match, he scored 36 and 76 not out on a turning pitch against Lancashire at Old Trafford in Manchester, putting on an unbroken century partnership with Ron Hamence in the second innings as the match ended in a draw.[5][27][28] Harvey was rested for the following match against Nottinghamshire, which was also drawn.[5][6]

Harvey returned in the next fixture against Hampshire and made one as Australia were dismissed for 117 in reply to the home side's 195. It was the first time the tourists had conceded a first innings lead on the tour.[6][29] However, Harvey did not get another chance with the bat as Australia recovered to win by eight wickets.[5][29]

Test omission

Harvey had one last chance to make his case for Test selection in the match at Hove against Sussex. It was the final county fixture before the First Test at Trent Bridge. He came to the crease at 3/360 and put on stands of 93 and 97 with Ray Lindwall and Hamence respectively to finish unbeaten on 100 in only 115 minutes. Australia declared at 5/549 when Harvey reached three figures and went on to complete an innings victory.[6][30] Former Australian Test batsman Jack Fingleton described Harvey's innings as "a superb century, rich in youthful daring and stroke production".[31] Harvey later rated it his best innings of the tour excluding the Test matches.[32]

Up to this point, the reserve opener Brown had scored 800 runs on tour at an average of 72.72, with a double century, three other centuries and 81 not out,[5] and was on his third tour of England.[33] In contrast, Harvey had totalled only 296 runs at 42.29 despite his unbeaten 100 against Sussex.[5]

Brown thus gained selection for the First Test, batting out of position in the middle order while Sid Barnes and Morris opened, whereas Harvey was dropped despite making a century in Australia's most recent Test against India.[21][34][35] This was the exact situation that had unfolded in the Worcestershire and MCC matches when Australia fielded their first-choice team; Harvey did not play and Brown batted out of position in the middle order.[7][26] There was a chance of Harvey receiving a last-minute call-up when Barnes was ill with food poisoning in the week leading up to the Test, but the opener recovered.[36]

Despite his omission, Harvey spent a large amount of the Test substituting as twelfth man for paceman Ray Lindwall, who succumbed to a hamstring injury in the first innings. Lindwall was nevertheless able to jog between the wickets when Australia batted, without needing a runner, but he did not take the field in the second innings. Fingleton said that Harvey was "by far the most brilliant fieldsman of both sides" and that Australia gained a substantial advantage through his presence on the ground.[37] England captain Norman Yardley was sceptical as to whether Lindwall was sufficiently injured to be unable to field, but he did not formally object to the presence of Harvey.[37] Former Australian Test cricket Bill O'Reilly said that Lindwall was demonstrably not "incapacitated" and that Yardley "must be condemned for carrying his concepts of sportsmanship too far".[38] O'Reilly decried the benefit that Australia derived through the substitution, agreeing with Fingleton that Harvey was the tourists' best fielder by far.[38] English commentator John Arlott went further, calling Harvey the best fielder in the world.[39] Australia went on to defeat England by eight wickets although Brown made only 17.[21]

Between Tests, Harvey was called in for the match against Northamptonshire, scoring only 14, while Brown was rested as Australia won by an innings.[5][6][40] In the second match before the next Test, which was against Yorkshire, Harvey made 49 and 56 while Brown made 19 and 113 as an opener.[41] Harvey hit the ball to all parts of the ground and Fingleton opined that "[Harvey] probably gained the respect of this most discerning crowd more quickly than any other cricketer in recent years".[42] However, Brown retained his middle-order position for the Second Test at Lord's ahead of Harvey; Australia fielded an unchanged team.[21][22][33][41] O'Reilly criticised the retention of Brown, who had appeared to be noticeably uncomfortable in the unfamiliar role. He said that despite the fact that Brown had made an unbeaten double century on his previous Test at Lord's in 1938, Loxton and Harvey had better claims to selection.[43] Bradman’s men went on to a crushing win by 409 runs, although Brown made only 24 and 32 in the middle order.[22]

The next match was against Surrey and started the day after the Second Test.[6] Brown injured a finger while fielding in the first innings, so he was not able to bat in Australia's first innings,[44] in which Harvey made 43 before being run out.[45] In the second innings, Harvey caught Surrey captain Errol Holmes from a leaping catch, snaffling the ball as it flew through a flock of pigeons.[46] On the final day, Australia wanted to finish the run-chase quickly so they could watch the Australian John Bromwich play in the Wimbledon tennis final. Harvey volunteered to play as a makeshift opener alongside Sam Loxton and promised Bradman that he would reach the target quickly. Australia chased down the 122 runs needed for victory in just 58 minutes to complete a 10-wicket win in just 20.1 overs. Harvey ended unbeaten on 73 and the Australians arrived at Wimbledon in time for the championship-deciding match.[5][6][45][46]

For the following match against Gloucestershire before the Third Test, Brown did not play.[6][47] Harvey came to the crease at 3/304 and put on 164 for the fourth wicket before his partner Morris was out for 294. He put on another 63 with Loxton before falling for 95.[47] During his innings, Harvey repeatedly advanced out of the crease to attack the spinners.[48] Loxton ended on 159 not out as Australia reached 7/774 declared, their highest score of the tour, which underpinned a dominant innings victory.[47] Harvey and the other Australian batsmen repeatedly left their crease to charge and attack the off spin of Tom Goddard, who ended with 0/186. Goddard had been touted as a possible England selection because the bowlers used in the first two Tests had failed to challenge the supremacy of Australia’s batsmen, but the tourists’ attack ended his prospects.[49] Loxton's innings earned him Brown's middle-order position for the Third Test at Old Trafford,[6][22][23][47] which was a rain-affected draw.[23]

Fourth Test

During the drawn Third Test, Barnes was injured and Ian Johnson was used as a makeshift opener because Morris was the only specialist opener left in the team after the omission of Brown.[50][51] In the meantime, Barnes's injury had opened up a vacancy for the Fourth Test. Harvey managed only ten and Brown only eight as Australia defeated Middlesex by ten wickets in their only county match between Tests.[5][6][52]

Despite his low score in the preceding match against Middlesex, Harvey was called into the team for the Fourth Test at Headingley at the expense of Barnes.[3] The selectors had overlooked Brown as a replacement for Barnes's opening position. Instead, vice-captain Hassett would move from the middle-order to accompany Morris at the top of the innings, while Harvey would slot into the middle-order.[23][24]

England batted first and amassed 496. Australia began their reply on the second afternoon and Bradman and Hassett saw the tourists to stumps at 1/63.[24] The next morning, Hassett and Bradman fell in one Dick Pollard over to leave Australia at 3/68 with two new batsmen at the crease.[51] Harvey came in bareheaded at No. 5 to join cavalier all-rounder Keith Miller. Australia were more than 400 behind and if England were to remove the pair, they would expose Australia's lower order and give themselves an opportunity to take a large first innings lead. Upon arriving in the middle Harvey told his senior partner "What's going on out here, eh? Let's get stuck into 'em".[53][54] Harvey got off the mark by forcing the ball behind point for a single.[55]

The pair launched a counterattack, with Miller taking the lead. He hoisted off spinner Jim Laker's first ball over square leg for six. Miller shielded Harvey from Laker, as the young batsman was struggling against the off breaks that were turning away from him, especially one ball that spun and bounced, beating his outside edge.[56] Miller drilled an off-drive from Laker for four, and then hit another flat over his head, almost for six into the sightscreen.[56] This allowed Australia to seize the initiative, and Harvey joined the fightback during the next over, hitting consecutive boundaries against Laker, the second of which almost cleared the playing area. He then took another boundary to reach 44, with Miller on 42.[57] Miller then lifted Laker for a six over long off, and a four over long on from Yardley to reach 54. Miller drove the next ball through cover for four. Yardley responded by stacking the on side with outfielders and bowling outside leg stump, challenging Miller to another hit for six. The batsman obliged, but edged the ball and was caught at short fine leg for 58.[57][58][59] The partnership yielded 121 runs in 90 minutes, and was likened by Wisden to a "hurricane".[60] Fingleton said that he had never "known a more enjoyable hour" of "delectable cricket".[61] O'Reilly said that Miller and Harvey had counter-attacked with "such joyful abandon that it would have been difficult, if not absolutely impossible, to gather from their methods of going about it that they were actually retrieving a tremendously difficult situation".[62] Arlott said that "two of the greatest innings of all Test cricket were being played" during the partnership.[63]

At 4/189 Loxton came in to join Harvey,[24] who continued to attack the bowling, unperturbed by Miller's demise. Ken Cranston came on to bowl and Harvey square drove and then hooked to deep square leg for consecutive boundaries. Yardley then moved a man from fine leg to where the hook had gone; Harvey responded by glancing a ball to the fielder's former position, collecting three more runs. Australia thus went to lunch at 4/204, with Harvey on 70.[64]

After lunch, Australia scored slowly as Loxton struggled. Yardley took the new ball in an attempt to trouble the batsmen with livelier bowling, but instead, Loxton began to settle in. He lofted Pollard to the leg side, almost for six, and then hit three boundaries off another over. Harvey accelerated as well, and 80 minutes into the middle session, reached his century to a loud reception as Australia passed 250. Harvey’s knock had taken 177 minutes and included 14 fours.[65] Loxton then dominated the scoring and brought up his 50 with a six.[65] The partnership yielded 105 in only 95 minutes. Harvey was eventually out for 112 from 183 balls, bowled by Laker while playing a cross-batted sweep. His shot selection prompted Bradman to throw his head back in disappointment.[66] Nevertheless, it was an innings noted for powerful driving on both sides of the wicket and the high rate of scoring helped to swing the match back from England's firm control.[1][51][60][67] Harvey fell at 5/294,[24] and Australia slumped to 8/355 before a counterattack by Ray Lindwall saw them to 458, restricting England's lead to 38.[24][51][68] O'Reilly said that Harvey's innings was one of "no inhibitions" and that it was "completely unspoiled by any preconceived plan to eliminate any particular shot".[62] He added that it was "the very mirror of truth in the batting art",[69] "delightfully untrammeled by the scourage of good advice or any other handicapping influence",[69] and that Harvey's innings was the most pleasing he had seen since Stan McCabe's 232 at Trent Bridge in 1938.[69]

England then progressed to 0/129 in their second innings before Harvey intervened. On 65, Cyril Washbrook attempted a hook from Bill Johnston. Connecting with the middle of the bat, he imparted much power on the ball, which flew flat and never went more than six metres above the ground,[70] but Harvey quickly ran across the ground and bent over to catch the ball at ankle height while still on the run. Jack Fingleton said that it "was the catch of the season—or, indeed, would have been had Harvey not turned on several magnificent aerial performances down at The Oval [against Surrey]".[71] O’Reilly doubted "whether any other player on either side could have made the distance to get to the ball, let alone make a neat catch of it".[72] He added that the "hook was a beauty and the catch was a classic".[70] Later in the day, captain Yardley was caught by a leaping Harvey while attempting a lofted shot from Johnston.[73]

After five minutes on the final morning, Yardley declared at 8/365.[51] Batting into the final day allowed Yardley to ask the groundsman to use a heavy roller, which would help to break up the wicket, thereby causing more uneven bounce and making the surface more likely to spin.[51] The declaration left Australia to chase 404 runs for victory. At the time, this would have been the highest ever fourth innings score to result in a Test victory for the batting side. Australia had only 345 minutes to reach the target, and the local press wrote them off, predicting that they would be dismissed by lunchtime on a deteriorating wicket expected to favour the spin bowlers.[74] However, Morris partnered Bradman in a stand of 301 in 217 minutes to set up the win, although they were helped by England’s fielders, who missed several catching and stumping chances.[51] Harvey came to the crease at 3/396 and got off the mark by hitting the winning boundary.[75]

Immediately after the Headingley Test, Harvey made 32 in a fleet-footed cameo attack against the local spinners as Australia amassed 456 and defeated Derbyshire by an innings.[6][76][77] In the next match against Glamorgan, he came to the crease at the fall of third wicket and made nine runs before rain ended the match in the second innings.[5][6][78] Harvey then made a duck, bowled by a big-turning leg break from Eric Hollies in the first innings as Australia defeated Warwickshire by nine wickets; he was not required to bat in the second innings.[5][79] Harvey was then rested as Australia faced and drew with Lancashire for the second time on the tour. He returned for the non-first-class match against Durham, scoring two out of Australia's 282 in a rain-affected draw, which ended after the first day without reaching the second innings.[6][80]

Fifth Test

Although he had only scored 41 runs in four innings between Tests, Harvey was retained for the Fifth and final Test at The Oval.[5] England elected to bat on a rain-affected pitch. Precipitation in the week leading up to the match had delayed the start,[81][82] and Yardley’s decision to bat was regarded as a surprise, as the weather suggested that bowlers would enjoy the conditions.[81] This proved to be correct as Australia cut England down for 52 on the first day, with Lindwall (6/20) in particular managing to make the ball bounce at variable heights.[82] Australia had already passed England by the close of play, reaching 2/153.[25] The next day, Harvey came to the crease at 4/243 and quickly displayed the exuberance of youth.[25] He hit Jack Young for a straight-driven four and then pulled him for another. Harvey then succumbed to Eric Hollies for 17, hitting a catch to Young, leaving Australia at 5/265.[25][83] The Warwickshire spinner noticed this, and delivered a topspinner that dipped more than usual, and the batsman mistimed his off-drive, which went in the air towards mid-off.[84] Australia finished at 389 and then bowled England out for 188 to complete victory by an innings and 149 runs and seal the series 4–0.[25][85]

Later tour matches

Seven matches remained on Bradman's quest to go through a tour of England without defeat.[6] Australia batted first against Kent and Harvey made 60, including a 104-run stand with Brown before falling at 4/283, part of a collapse in which Australia lost their last seven wickets for 89 to end at 361.[86] Despite stumbling with the bat, the tourists completed an innings victory.[5] In the next match against the Gentlemen of England, Harvey was rested as Australia amassed 5/610 and won by an innings.[6][87] He returned for the match against Somerset, putting on 187 for the second wicket with Hassett in 110 minutes. Harvey hit 14 fours and 2 sixes, both of which came in one over, in top-scoring with a "glorious" 126 as Australia compiled 5/560 declared and won by an innings and 374 runs.[5][6][88][89][90] Harvey performed a similar feat in the following match against the South of England, coming in at 3/237 and scoring 110, adding 175 in 110 minutes in conjunction with Hassett, who also made a second successive century as Australia declared at 7/522. Harvey reached his century in just 90 minutes.[91] The match was washed out, but not before Harvey bowled for the first time during the tour and took his only first-class wicket for the season, that of Trevor Bailey. He ended with 1/15.[5][6][92]

Australia's biggest challenge in the post-Test tour matches was against the Leveson-Gower's XI. During the last Australian tour in 1938, Leveson-Gower’s team was effectively a full-strength England outfit, but this time Bradman insisted that only six current England Test players be allowed to play.[93][94] Bradman then fielded a full-strength team,[93] with the only difference from the Fifth Test team being the inclusion of Ian Johnson at the expense of Doug Ring. Harvey made 23 before being bowled by Freddie Brown as the match ended in a draw after multiple rain delays.[25][95] For the entire first-class tour, Harvey scored four centuries and aggregated 1,129 runs at 53.76.[96]

The tour ended with two non-first-class matches against Scotland. In the first match, Harvey was rested as the Australians took an innings victory. In the second match, Harvey scored four and then took 2/13 in the second innings as Australia ended their campaign with another innings victory.[5][6]

Role

At the age of 19, Harvey was the youngest player of the touring party—more than six and half years younger than all the other members of the squad.[1][60] An attacking left-handed middle-order batsman, Harvey had become the youngest Australian to score a Test century, by making 153 in the Fifth Test against India in the preceding Australian summer. However, Harvey struggled early in the tour and had difficulty adapting to English conditions. After being omitted from the first-choice team in the early part of the tour, Harvey's performances improved with increasing familiarity with local conditions,[5] and he was called into the team for the Fourth Test, where he batted at No. 5 behind Miller and in front of Loxton due to the injury to Barnes. Upon Barnes’ return for the Fifth Test, the trio were each pushed down one position.[24][25]

Overall, Harvey ended with 1,129 runs at 53.76 in the first-class matches with four centuries, placing him sixth on the aggregates and seventh in the batting averages.[97] He played the bulk of his 27 first-class innings between No. 4 and No. 6 in the batting order. Only three times did he bat elsewhere. He scored an unbeaten 73 in less than an hour in the second innings of the second match against Surrey as a makeshift opener,[44] setting up a ten-wicket victory. He made 23 batting at No. 3 against Oxford University and one against Hampshire while batting at No. 7.N-[1]

Harvey was an acrobatic fielder, regarded as the best in the Australian team. Fingleton said that Harvey was "by far the most brilliant fieldsman of both sides, who was to save many runs in the field".[37] O'Reilly agreed Fingleton that Harvey was Australia's best fielder by far,[38] Arlott went further, calling Harvey the best fielder in the world.[39] He was twelfth man in the early Tests because of his fielding ability, before breaking into the playing XI and taking several acclaimed catches throughout the tour.[46] He took 17 catches for the tour and claimed a solitary wicket with his occasional off spin, bowling only ten overs for the entire summer.[97]

See also

Notes

n-[1] a This statement can be verified by consulting all of the scorecards for the matches, as listed here.[7][9][12][15][18][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][29][30][40][41][45][47][52][78][80][86][87][88][92][95][98][99][100][101][102][103][104]

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Cashman, pp. 117–119.

- ↑ Cashman, pp. 118, 153, 174, 176, 215–216.

- 1 2 3 4 Perry (2002), p. 101.

- ↑ Haigh, Gideon (2007-05-26). "Gentrifying the game". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 "Player Oracle RN Harvey 1948". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 "Matches, Australia tour of England, Apr-Sep 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- 1 2 3 "Worcestershire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 "Leicestershire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 50.

- ↑ Fingleton, pp. 53–55.

- 1 2 3 4 "Yorkshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 Fingleton, p. 55.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 56.

- 1 2 "Surrey v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 62.

- ↑ Perry (2008), p. 53.

- 1 2 "Cambridge University v Australians". CricketArchive. 1948-05-12. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Fingleton, pp. 65–67.

- 1 2 "Oxford University v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "1st Test England v Australia at Nottingham Jun 10–15 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "2nd Test England v Australia at Lord's Jun 24–29 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "3rd Test England v Australia at Manchester Jul 8-13 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "4th Test England v Australia at Leeds Jul 22-27 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "5th Test England v Australia at The Oval Aug 14–18 1948". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- 1 2 3 "MCC v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 "Lancashire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Perry (2008), pp. 79–82.

- 1 2 3 "Hampshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 "Sussex v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 79.

- ↑ Perry (2008), p. 94.

- 1 2 Hodgson, Derek (2008-03-18). "Bill Brown: Accomplished batsman who scored handsomely for Australia before and after the war |". The Times. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ "Statsguru - Australia - Tests - Results list". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ Perry (2002), p. 100.

- ↑ Perry (2008), p. 96.

- 1 2 3 Fingleton, p. 96.

- 1 2 3 O'Reilly, p. 42.

- 1 2 Arlott, p. 41.

- 1 2 "Northamptonshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 3 "Yorkshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 193.

- ↑ O'Reilly, p. 59.

- 1 2 "Australians in England, 1948". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack (1949 ed.). pp. 237–238.

- 1 2 3 "Surrey v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 3 Fingleton, p. 196.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Gloucestershire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ↑ Perry (2008), p. 154.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 199.

- ↑ "Third Test Match England v Australia". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. 1949. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Fourth Test Match England v Australia". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. 1949. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- 1 2 "Middlesex v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Perry, p. 245.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 161.

- ↑ Fingleton, pp. 161–162.

- 1 2 Fingleton, p. 162.

- 1 2 Fingleton, p. 163.

- ↑ Perry, p. 246.

- ↑ Arlott, pp. 108–109.

- 1 2 3 "Wisden 1954 — Neil Harvey". Wisden. 1954. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ↑ Fingleton, pp. 162–163.

- 1 2 O'Reilly, p. 124.

- ↑ Arlott, p. 108.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 164.

- 1 2 Fingleton, p. 165.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 166.

- ↑ Perry (2005), p. 247.

- ↑ Pollard (1990), p. 14.

- 1 2 3 O'Reilly, p. 125.

- 1 2 O'Reilly, p. 134.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 170.

- ↑ O’Reilly, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 172.

- ↑ Perry (2001), pp. 84–89.

- ↑ Perry (2002), pp. 101–102.

- ↑ "Derbyshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ↑ Perry (2008), p. 211.

- 1 2 "Glamorgan v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Perry (2008), p. 216.

- 1 2 "Durham v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 Fingleton, p. 183.

- 1 2 "Fifth Test Match England v Australia". Wisden Cricketers' Almanack. 1949. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 188.

- ↑ O'Reilly, p. 153.

- ↑ "Statsguru - RN Harvey - Tests - Innings by innings list". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- 1 2 "Kent v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- 1 2 "Gentlemen v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- 1 2 "Somerset v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Perry (2008), p. 153.

- ↑ Fingleton, p. 208.

- ↑ Perry (2008), p. 256.

- 1 2 "South of England v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- 1 2 Perry (2005), pp. 253–254.

- ↑ Fingleton, pp. 207–209.

- 1 2 "H.D.G. Leveson-Gower's XI v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Perry (2000), p. 228.

- 1 2 "Batting and bowling averages Australia tour of England, Apr-Sep 1948 - First-class matches". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- ↑ "Essex v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "Nottinghamshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "Derbyshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "Warwickshire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "Lancashire v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "Scotland v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ "Scotland v Australians". CricketArchive. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

References

- Arlott, John (1949). Gone to the test match : being primarily an account of the test series of 1948. London: Longmans.

- Cashman, Richard; Franks, Warwick; Maxwell, Jim; Sainsbury, Erica; Stoddart, Brian; Weaver, Amanda; Webster, Ray (1997). The A–Z of Australian cricketers. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-9756746-1-7.

- Fingleton, Jack (1949). Brightly fades the Don. London: Collins.

- O'Reilly, W. J. (1949). Cricket conquest: the story of the 1948 test tour. London: Werner Laurie.

- Perry, Roland (2001). Bradman's best: Sir Donald Bradman's selection of the best team in cricket history. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House Australia. ISBN 0-09-184051-1.

- Perry, Roland (2002). Bradman's best Ashes teams: Sir Donald Bradman's selection of the best ashes teams in cricket history. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House Australia. ISBN 1-74051-125-5.

- Perry, Roland (2005). Miller's Luck: the life and loves of Keith Miller, Australia's greatest all-rounder. Milsons Point, New South Wales: Random House. ISBN 978-1-74166-222-1.

- Perry, Roland (2008). Bradman's invincibles : the inside story of the epic 1948 Ashes Tour. Sydney, New South Wales: Hachette. ISBN 978-0-7336-2279-3.

- Pollard, Jack (1990). From Bradman to Border: Australian Cricket 1948–89. North Ryde, New South Wales: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-207-16124-0.