Open the Door, Richard

| "Open the Door, Richard" | |

|---|---|

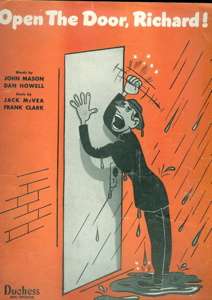

Sheet music for "Open the Door, Richard" | |

| Single by Jack McVea and His All Stars | |

| B-side | "Lonesome Blues" |

| Released | 1946 |

| Format | 10" 78 rpm record |

| Recorded | 1946 |

| Genre | Rhythm and blues, novelty song |

| Length | 2:58 |

| Label | Black & White (Cat. no. 792) |

| Writer(s) | Jack McVea, Frank Clarke |

"Open the Door, Richard" is a song first recorded by the saxophonist Jack McVea for Black & White Records at the suggestion of A&R man Ralph Bass. In 1947, it was the number-one song on Billboard's "Honor Roll of Hits" and became a runaway pop sensation.[1]

Origin

"Open the Door, Richard" started out as a black vaudeville routine. Pigmeat Markham, one of several who performed the routine, attributed it to his mentor Bob Russell.[2] The routine was made famous by Dusty Fletcher on stages such as the Apollo Theater in New York and in a short film [Archive.org]. Dressed in rags, drunk, and with a ladder as his only prop, Fletcher would repeatedly plunk the ladder down stage center, try to climb it to knock on an imaginary door, then crash sprawling on the floor after a few steps while shouting, half-singing "Open the Door, Richard". After this he would mutter a comic monologue, then try the ladder again and repeat the process, while the audience was imagining what Richard was so occupied doing.[3]

Jack McVea was responsible for the musical riff associated with the phrase "Open the Door, Richard",[4] which became familiar to radio listeners. Fourteen different recordings of the song were made.

Song

In the song, accompanied by a rhythm section and McVea's expressive tenor honking, the intoxicated, rowdy band members come home late at night, knowing Richard has the only key to the house. Knocking and repeated calls from McVea and the band members for Richard to open the door get no result. The musical refrain kicks in with the musicians singing in unison:

- Open the door, Richard,

- Open the door and let me in,

- Open the door, Richard,

- Richard, why don't you open that door!

The spoken dialogue makes humorous references to negative aspects of urban African-American life, including poverty and police brutality. The narrator explains, "I know he's in there, 'cause I got on the clothes." He also says, "I was on relief, but they got short of help and you had to go downtown to pick up the checks, so I gave it up." Later, when a policeman tells him to come down from the ladder and begins hitting his feet, the narrator protests, "You act like one of them police that ain't never arrested nobody before." Although the neighbors are being disturbed, McVea continues knocking as the song fades away.[5]

Charting versions

The original recording, by Jack McVea, recorded in October 1946,[4] was released by Black & White Records as catalogue number 792. It entered the Billboard Best Seller chart on February 14, 1947, and lasted two weeks there, peaking at number seven.[6] The recording is notable as one of the first to end with a fade-out (instead of the "cold" or final note ending commercial records that had heretofore been employed).[7]

The recording by Count Basie was released by RCA Victor Records as catalogue number 20-2127. It entered the Billboard Best Seller chart on February 7, 1947, and lasted four weeks there, peaking at number one.[6]

The recording by Dusty Fletcher was released by National Records as catalogue number 4012. It entered the Billboard Best Seller chart on January 31, 1947, and lasted five weeks there, peaking at number three.[6]

The recording by the Three Flames was released by Columbia Records as catalogue number 37268. It entered the Billboard Best Seller chart on February 14, 1947, and lasted three weeks there, peaking at number four.[6]

The recording by Louis Jordan was released by Decca Records as catalogue number 23841. It entered the Billboard Best Seller chart on March 7, 1947, and lasted two weeks there, peaking at number seven.[6]

For all the artists above except Jordan, this was their only hit on the charts. (This even includes Count Basie, despite his great fame, and despite the fact that this was a number-one hit for him. In Whitburn's Pop Memories, Basie was indeed recognized for his many chart singles outside the retail Top 10. The Basie string of "hits" continued on different Billboard charts through 1968.)

A non-charting version recorded by Tsai Chin and released in 1965 by UK Decca Records as "The Western World of Tsai Chinn", catalogue number LK 4717, in with an arrangement by Harry Robinson, is worthy of note. McVea is credited as the composer. It has an amusing conclusion, with Chin finally being admitted by "Christopher".

Copyright fight

The origins of the piece in a vaudeville routine led to there being several claimants to the rights. Russell was no longer alive, but both Mason and Fletcher came forth claiming to have written it; Fletcher even claimed that he had written the tune. By the time the dust settled, the official credits read "Words by Dusty Fletcher and John Mason, music by Dusty Fletcher and Don Howell". Howell appears to have been an entirely fictional front through which someone managed to pocket some of the royalties at McVea's expense.[8]

Legacy

"Open the Door, Richard" was an early R&B novelty record, a song category that became a basic genre of rock and roll in the 1950s. It also started the fad of answer songs.

When "Open the Door, Richard" landed on the "Honor Roll of Hits", it joined such white pop songs as "Zip-a-Dee Doo-Dah" for a Walt Disney film. But a black ballad, "(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons", sung by Al Jolson, was also on the list. These two songs became the first rhythm and blues songs since "I Wonder" to achieve sensational success in the white market and indicated that the pop mainstream was open to R&B.[1]

The phrase "Open the Door, Richard" passed into African American Vernacular English and became associated with the civil rights movement. When college students marched in 1947 to the state capitol demanding the resignation of segregationist governor Herman Talmadge, some of their banners read "Open the Door Herman". The Los Angeles Sentinel used "Open the Door Richard" as the title of an editorial demanding black representation in city government, and a Detroit minister used the title for a sermon on open housing.[9]

"Open the Door, Richard" also became a catchphrase in broader American society. It was used in routines by Jack Benny, Fred Allen, and Phil Harris. Jimmy Durante and Burl Ives each recorded versions of the song; the opera star Lauritz Melchior performed it on national radio. Molly Picon recorded a Yiddish version; it was also covered in Spanish, Swedish, French, Armenian and Hungarian. There were "Richard" hats, shirts, and jeans, and ads for products ranging from ale to perfume incorporated references to the song.[10]

A variant of the phrase ("Open the window, Richard") was used in the 1947 Looney Tunes short Crowing Pains.

Another reference appears in a 1949 Looney Tunes cartoon, High Diving Hare, featuring Yosemite Sam and Bugs Bunny (a riff on the song also appears in this cartoon). In the cartoon, Sam climbs up the ladder of a high-dive board, only to find a door on it. When he tries to open it he shouts, "Open up that door!!", then tells the audience, "D'ja notice I didn't say 'Richard'?"

North Carolina artist Pigmeat Markham released a version of the song for Chess Records in 1964.

In 1967, Bob Dylan and the Band recorded an homage to the song as part of The Basement Tapes. Entitled "Open the Door, Homer", the chorus nevertheless repeated the phrase "Open the door, Richard."

Ray Stevens covered the song on his 2012 box set, The Encyclopedia of Recorded Comedy Music.

The theme of the unanswered door and the lover also appears in the songs "I Hear You Knockin'" and "Keep A-Knockin'".

The Cuban Boys released a re-mix of the song with the same title on their 2000 EP Old Skool for Scoundrels.

In 1952 Tex Williams and Jesse Ashlock wrote what is likely a response song, entitled "Close the Door, Richard, I Just Saw the Thing".

The comedy routine "Dave's Not Here", by Cheech & Chong, was inspired by the song.

Notes

- 1 2 Shaw, Arnold (1978). Honkers and Shouters. New York: Macmillan. pp. 226–227. ISBN 0-02-061740-2.

- ↑ Smith (2004). pp. 78, 341n. According to Markham, Russell wrote the piece for a show called Mr. Rareback, in which the comedian John Mason performed it (and presumably expanded it in improvisation). Mason, Russell, and Markham were all African-American comedians; all performed in blackface.

- ↑ Fox, Ted (1993). Showtime at the Apollo (2nd ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. p. 96. ISBN 0-306-80503-0.

- 1 2 Smith (2004). p. 76.

- ↑ Dawson, Jim; Propes, Steve (1992). What Was the First Rock'n'Roll Record. Boston & London: Faber & Faber. pp. 21–25. ISBN 0-571-12939-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whitburn, Joel (1973). Top Pop Records 1940–1955. Record Research.

- ↑ Robert Petway's "Catfish Blues" is believed to be the first commercial recording to employ the technique of fading out at the end of a record. It was recorded March 28, 1941, in Chicago, and subsequently released as Bluebird B8838.

- ↑ Smith (2004). p. 81–82.

- ↑ Smith (2004). pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Smith (2004). p. 84–85.

References

- Smith, R. J. (2004). "Richard Speaks! Chasing a Tune from the Chitlin Circuit to the Mormon Tabernacle". pp. 75–89 in Weisbard, Eric, ed. This is Pop Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01321-2 (cloth), ISBN 0-674-01344-1 (paper).

| Preceded by "(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons" by The King Cole Trio |

U.S. Billboard Best Sellers in Stores number-one single February 22, 1947 |

Succeeded by "Managua, Nicaragua" by Freddy Martin |