Parklife

| Parklife | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Blur | ||||

| Released | 25 April 1994 | |||

| Recorded | August 1993 – January 1994 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | Britpop | |||

| Length | 52:39 | |||

| Label | Food, SBK | |||

| Producer | Stephen Street, Stephen Hague, John Smith and Blur | |||

| Blur chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Parklife | ||||

|

||||

Parklife is the third studio album by the English rock band Blur, released in April 1994 on Food Records. After disappointing sales for their previous album Modern Life Is Rubbish (1993), Parklife returned Blur to prominence in the UK, helped by its four hit singles: "Girls & Boys", "End of a Century", "Parklife" and "To the End".

Certified four times platinum in the United Kingdom,[1] in the year following its release the album came to define the emerging Britpop scene, along with the album Definitely Maybe by rivals Oasis. Britpop in turn would form the backbone of the broader Cool Britannia movement. Parklife therefore has attained a cultural significance above and beyond its considerable sales and critical acclaim, cementing its status as a landmark in British rock music. It has sold over five million copies worldwide.

Recording

After the completion of recording sessions for Blur's previous album, Modern Life Is Rubbish, Damon Albarn, the band's vocalist, began to write prolifically. Blur demoed Albarn's new songs in groups of twos and threes.[2] Due to their precarious financial position at the time, Blur quickly went back into the studio with producer Stephen Street to record their third album.[3] Blur met at the Maison Rouge recording studio in August 1993 to record their next album.[2] The recording was a relatively fast process, apart from the song "This Is a Low".

While the members of Blur were pleased with the final result, Food Records owner David Balfe was not pleased with the record, telling the band's management "This is a mistake". Soon afterwards, Balfe sold Food to EMI.[4]

Music

Blur frontman Damon Albarn told NME in 1994, "For me, Parklife is like a loosely linked concept album involving all these different stories. It's the travels of the mystical lager-eater, seeing what's going on in the world and commenting on it." Albarn cited the Martin Amis novel London Fields as a major influence on the album. Oasis guitarist Noel Gallagher was once quoted saying that Parklife was, "Like Southern England personified".[5] The songs themselves span many genres, such as the synthpop-influenced hit single "Girls & Boys", the instrumental waltz interlude of "The Debt Collector", the punk rock-influenced "Bank Holiday", the spacey, Syd Barrett-esque "Far Out",[6] and the fairly new wave-influenced "Trouble in the Message Centre". Journalist John Harris commented that while many of the album's songs "reflected Albarn's claims to a bittersweet take on the UK's human patchwork", he stated that several songs, including "To the End" (featuring Lætitia Sadier of Stereolab) and "Badhead" "lay in a much more personal space".[7]

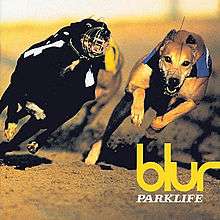

Title and cover

The album was originally going to be entitled London and the album cover shot was going to be of a fruit-and-vegetable cart. Albarn stated tongue-in-cheek, "That was the last time that Dave Balfe was, sort of, privy to any decision or creative process with us, and that was his final contribution: to call it London".[8] The cover refers to the British pastime of greyhound racing.[9] Most of the pictures in the CD booklet are of the band in the greyhound racing venue Walthamstow Stadium, although the actual cover was not shot there.[10] The album cover for Parklife was among the ten chosen by the Royal Mail for a set of "Classic Album Cover" postage stamps issued in January 2010.[11][12]

Release

Reception

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| NME | 9/10[17] |

| Pitchfork Media | 9.5/10[18] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Select | 5/5[22] |

Upon release, Parklife debuted at number one on the UK Album Charts and stayed on the chart for 90 weeks.[23][24] It reached number six on the Billboard Top Heatseekers album chart in the United States.[25] Johnny Dee, reviewing Parklife for NME, called it "a great pop record", adding "On paper it sounds like hell, in practice it's joyous."[17] Paul Evans of Rolling Stone stated that with "one of this year's best albums", the band "realize their cheeky ambition: to reassert all the style and wit, boy bonding and stardom aspiration that originally made British rock so dazzling."[20] Conversely, Robert Christgau of The Village Voice indicated that the only good song on the album was "Girls & Boys".[26]

Parklife remains one of the most acclaimed albums of the 1990s. In a retrospective review, AllMusic's Stephen Thomas Erlewine commented: "By tying the past and the present together, Blur articulated the mid-'90s zeitgeist and produced an epoch-defining record."[13]

Accolades

Parklife has received accolades since its official release and is largely seen not only as one of the best albums of 1994 and its decade, but of all time. The album was nominated to the 1995 Mercury Prize, but it lost to M People's Elegant Slumming.[27] Blur also won four awards at the 1995 Brit Awards, including Best British Album for Parklife.[28] The album was listed as one of the 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[29]

In 2003, Pitchfork Media placed the album at number 54 on their Top 100 Albums of the 1990s list.[30]

In 2006, British Hit Singles & Albums and NME organised a poll of which, 40,000 people worldwide voted for the 100 best albums ever and Parklife was placed at number 34 on the list.[31] The album has been hailed as a "Britpop classic".[32] Parklife influenced a number of British guitar bands, including Supergrass, Gene, Echobelly and Menswear.[33]

In July 2014, Guitar World placed Parklife in its "Superunknown: 50 Iconic Albums That Defined 1994" list.[34] The album was ranked at number 171 on Spin's "The 300 Best Albums of the Past 30 Years (1985–2014)" list.[35]

Track listing

All music by Blur and all lyrics by Albarn, except "Far Out" written by James.

- "Girls & Boys" – 4:50

- "Tracy Jacks" – 4:20

- "End of a Century" – 2:46

- "Parklife" (starring Phil Daniels) – 3:05

- "Bank Holiday" – 1:42

- "Badhead" – 3:25

- "The Debt Collector" – 2:10

- "Far Out" – 1:41

- "To the End" – 4:05

- "London Loves" – 4:15

- "Trouble in the Message Centre" – 4:09

- "Clover Over Dover" – 3:22

- "Magic America" – 3:38

- "Jubilee" – 2:47

- "This Is a Low" – 5:07

- "Lot 105" – 1:17

Personnel

- Blur

- Damon Albarn – lead and backing vocals, keyboards, hammond organ, moog synthesizer, machine strings, harpsichord on "Clover Over Dover", melodica, vibraphone, recorder, programming

- Graham Coxon – guitars, backing vocals, clarinet, saxophone, percussion

- Alex James – bass guitar, vocals on "Far Out"

- Dave Rowntree – drums, percussion, programming

|

|

Charts and certifications

Weekly charts

|

Certifications

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Harris, John. Britpop! Cool Britannia and the Spectacular Demise of English Rock, 2004. ISBN 0-306-81367-X

Notes

- ↑ "Damon Albarn on Blur's Parklife, 20 years on". BBC News. 26 April 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- 1 2 Cavanagh, David; Maconie, Stuart. "How did they do that? – Parklife". Select. May 1995

- ↑ Harris, p. 97

- ↑ Harris, p. 139

- ↑ Moody, Paul. "We Can Be Eros Just For One Day". NME. 5 March 1994.

- ↑ Easlea, Daryl (23 April 2007). "Review of Blur – Parklife". BBC Music. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ Harris, p. 140

- ↑ Essential Albums of the 90s: Blur – Parklife BBC/6music. Aired on 10 November 2010.

- ↑ "Blur – Parklife (album review)". Sputnikmusic. 16 January 2005. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ↑ "Dog track that inspired Blur's 'Parklife' album art to close". NME. 20 May 2008. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ↑ "Classic Album Covers: Issue Date – 7 January 2010". Royal Mail. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ Michaels, Sean (8 January 2010). "Coldplay album gets stamp of approval from Royal Mail". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- 1 2 Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Parklife – Blur". AllMusic. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ↑ Kot, Greg (7 July 1994). "Brilliant Brits". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ↑ Larkin, Colin (2007). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-857-12595-8.

- ↑ Hochman, Steve (19 June 1994). "In Brief". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- 1 2 Dee, Johnny (April 1994). "Blur – Parklife". NME. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ Zoladz, Lindsay (31 July 2012). "Blur: Blur 21". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ↑ Maconie, Stuart (June 1994). "Blur: Parklife". Q (93).

- 1 2 Evans, Paul (30 June 1994). "Parklife". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian, eds. (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. Simon & Schuster. pp. 89–90. ISBN 0-743-20169-8.

- ↑ Harrison, Andrew (June 1994). "Yobs for the Boys". Select (48): 84–85.

- 1 2 "Blur". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ↑ Harris, p. 142

- ↑ "Parklife – Blur – Charts & Awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ Christgau, Robert (6 June 1995). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ↑ Hughes, Jack (18 September 1994). "Cries & Whispers". The Independent. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ↑ "The BRITs 1995". The BRIT Awards. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die". rocklist.net. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Top 100 Albums of the 1990s". Pitchfork Media. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ "Oasis album voted greatest of all time". The Times. 1 June 2006

- ↑ Jason Dietz (2 March 2010). "Inside the Gorillaverse: A Look at Alt-Rock's Best Cartoon Band". CBS Interactive. Metacritic. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ↑ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. Parklife at AllMusic. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- ↑ "Superunknown: 50 Iconic Albums That Defined 1994". GuitarWorld.com. July 14, 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ↑ Unterberger, Andrew (11 May 2015). "The 300 Best Albums of the Past 30 Years (1985-2014)". Spin. p. 3. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ "Parklife – Blur – Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Australian chart positions". australian-charts.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?lr=&rview=1&id=TAgEAAAAMBAJ&q=blur#v=snippet&q=blur&f=false

- ↑ source: Pennanen, Timo: Sisältää hitin - levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla vuodesta 1972. Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava, 2006. ISBN 9789511210535. page: 280

- ↑ https://books.google.com/books?lr=&rview=1&id=9A0EAAAAMBAJ&q=blur#v=onepage&q=blur&f=false

- ↑ ブラーのCDアルバムランキング "Japanese chart positions" Check

|url=value (help). Oricon Style. Retrieved 16 October 2012. - ↑ "New Zealand chart positions". charts.org.nz. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ "Norwegian chart positions". norwegiancharts.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ Steffen Hung. "Blur - Parklife - swisscharts.com". swisscharts.com. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ↑ "Gold and Platinum Search". web.archive.org. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- 1 2 "content/section_news/plat1996". ifpi.org. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2011.