Disphenoid

The tetragonal and digonal disphenoids can be positioned inside a cuboid bisecting two opposite faces. The tetragonal form has Coxeter diagram |

A rhombic disphenoid has 4 congruent scalene triangle faces, and can fit diagonally inside of a cuboid. It has three sets of edge lengths, existing as opposite pairs. It can be given Coxeter diagram |

In geometry, a disphenoid (also bisphenoid) (from Greek sphenoeides, "wedgelike" [1]) is a tetrahedron whose four faces are congruent acute-angled triangles.[2] It can also be described as a tetrahedron in which every two edges that are opposite each other have equal lengths. Other names are isosceles tetrahedron and equifacial tetrahedron. They can also be seen as digonal antiprisms or as alternated quadrilateral prisms. All the solid angles and vertex figures of a disphenoid are the same, and the sum of the face angles at each vertex is equal to two right angles. However, a disphenoid is not a regular polyhedron, because, in general, its faces are not regular polygons, and it is not edge-transitive .

Special cases and generalizations

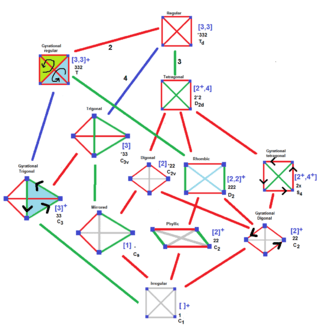

If the faces of a disphenoid are equilateral triangles, it is a regular tetrahedron with Td tetrahedral symmetry, although this is not normally called a disphenoid. The faces of a tetragonal disphenoid are identical isosceles, and it has D2d dihedral symmetry. The faces of a rhombic disphenoid are scalene and it has D2 dihedral symmetry. Tetragonal disphenoids and rhombic disphenoids are isohedra.

The digonal disphenoid is not a disphenoid as defined above. It has two sets of isosceles triangles faces, and it has C2v. The most general disphenoid term is the phyllic disphenoid with only two types of scalene triangles. Tetrahedral diagrams are included for each type below, with edges colored by isometric equivalence, and are gray colored for unique edges.

| Name | Edge diagram |

Faces | Symmetry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schön. | Coxeter | Orb. | Ord. | ||||

| Regular tetrahedron {3,3} or 4.( ) |

|

Identical equilateral triangles |

Td T | [3,3] [3,3]+ | *332 332 | 24 12 | |

| Tetragonal disphenoid s{2,4} or 2.{ } |

|

Identical isosceles triangles |

D2d S4 | [2+,4] [2+,4+] | 2*2 2× | 8 4 | |

| Rhombic disphenoid sr{2,2} |

Identical scalene triangles |

D2 | [2,2]+ | 222 | 4 | ||

| Digonal disphenoid { }∨{ } |

Two equilateral and two isosceles triangles |

C2v C2 | [2] [2]+ | *22 22 | 4 2 | ||

| Two types of isosceles triangles | |||||||

| Phyllic disphenoid | C2 | [2]+ | 22 | 2 | |||

| Two types of scalene triangles | |||||||

Characterizations

A tetrahedron is a disphenoid if and only if its circumscribed parallelepiped is right-angled.[3]

We also have that a tetrahedron is a disphenoid if and only if the center in the circumscribed sphere and the inscribed sphere coincide.[4]

Another characterization states that if d1, d2 and d3 are the common perpendiculars of AB and CD; AC and BD; and AD and BC respectively in a tetrahedron ABCD, then the tetrahedron is a disphenoid if and only if d1, d2 and d3 are pairwise perpendicular.[3]

The disphenoids are the only polyhedra having infinitely many non-self-intersecting closed geodesics. On a disphenoid, all closed geodesics are non-self-intersecting.[5]

Metric formulas

The volume of a disphenoid with opposite edges of length l, m and n is given by[6]

The circumscribed sphere has radius[6] (the circumradius)

and the inscribed sphere has radius[6]

where V is the volume of the disphenoid and T is the area of any face, which is given by Heron's formula. There is also the following interesting relation connecting the volume and the circumradius:[6]

The squares of the lengths of the bimedians are[6]

Other properties

If the four faces of a tetrahedron have the same perimeter, then the tetrahedron is a disphenoid.[4]

If the four faces of a tetrahedron have the same area, then it is a disphenoid.[3][4]

The centers in the circumscribed and inscribed spheres coincide with the centroid of the disphenoid.[6]

The bimedians are perpendicular to the edges they connect and to each other.[6]

Honeycombs and crystals

Some tetragonal disphenoids will form honeycombs. The disphenoid whose four vertices are (-1, 0, 0), (1, 0, 0), (0, 1, 1), and (0, 1, -1) is such a disphenoid.[7] Each of its four faces is an isosceles triangle with edges of lengths √3, √3, and 2. It can tessellate space to form the disphenoid tetrahedral honeycomb. As Gibb[8] describes, it can be folded without cutting or overlaps from a single sheet of a4 paper.

"Disphenoid" is also used to describe two forms of crystal:

- A wedge-shaped crystal form of the tetragonal or orthorhombic system. It has four triangular faces that are alike and that correspond in position to alternate faces of the tetragonal or orthorhombic dipyramid. It is symmetrical about each of three mutually perpendicular diad axes of symmetry in all classes except the tetragonal-disphenoidal, in which the form is generated by an inverse tetrad axis of symmetry.

- A crystal form bounded by eight scalene triangles arranged in pairs, constituting a tetragonal scalenohedron.

See also

- Orthocentric tetrahedron

- Snub disphenoid - A Johnson solid with 12 equilateral triangle faces and D2d symmetry.

- Trirectangular tetrahedron

References

- ↑ Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary.

- ↑

- Coxeter, Regular Polytopes, 3rd. ed., Dover Publications, 1973. ISBN 0-486-61480-8. p. 15

- 1 2 3 Andreescu, Titu and Gelca, Razvan, "Mathematical Olympiad Challenges", Birkhäuser, second edition, 2009, pp. 30-31.

- 1 2 3 Brown, B. H., "Theorem of Bang. Isosceles tetrahedra", American Mathematical Monthly, April 1926, pp. 224-226.

- ↑ Fuchs, Dmitry; Fuchs, Ekaterina (2007), "Closed geodesics on regular polyhedra" (PDF), Moscow Mathematical Journal, 7 (2): 265–279, 350, MR 2337883.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Leech, John (1950), "Some properties of the isosceles tetrahedron", Mathematical Gazette, 34 (310): 269–271, doi:10.2307/3611029.

- ↑ Coxeter, pp. 71–72; Senechal, Marjorie (1981). "Which tetrahedra fill space?". Mathematics Magazine. 54 (5): 227–243. doi:10.2307/2689983. JSTOR 2689983.

- ↑ Gibb, William (1990). "Paper patterns: solid shapes from metric paper". Mathematics in School. 19 (3): 2–4. Reprinted in Pritchard, Chris, ed. (2003). The Changing Shape of Geometry: Celebrating a Century of Geometry and Geometry Teaching. Cambridge University Press. pp. 363–366. ISBN 0-521-53162-4.