Pokhara

| Pokhara Sub-Metropolitan City पोखरा उप-महानगरपालिका | |

|---|---|

|

City Urban, Hilly | |

|

Top: View of the Annapurna Range from Pokhara; Center: Panorama of Pokhara; Bottom from left: Pokhara Valley, the Talbarahi Mandir in Phewa Tal, World Peace Pagoda in Pokhara. | |

| Nickname(s): The Lake City, The Fishtail City | |

| Motto: Clean Pokhara, Green Pokhara; | |

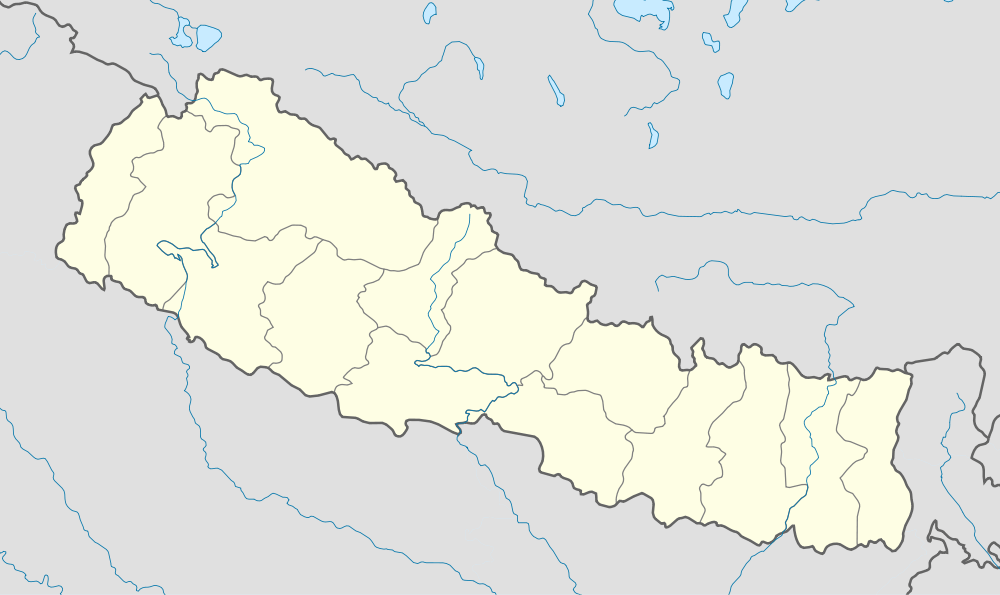

Pokhara Sub-Metropolitan City Location in Nepal | |

| Coordinates: 28°15′50″N 83°58′20″E / 28.26389°N 83.97222°ECoordinates: 28°15′50″N 83°58′20″E / 28.26389°N 83.97222°E | |

| Country | Nepal |

| Number 4 | Federal State |

| Zone | Gandaki Zone |

| District | Kaski District |

| Incorporated | 1962 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 56.00 km2 (21.62 sq mi) |

| • Water | 4.4 km2 (1.7 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,740 m (5,710 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 827 m (2,713 ft) |

| Population (2011 (last census)) | |

| • Total | 353,841 |

| • Density | 4,954.45/km2 (12,832.0/sq mi) |

| • Ethnicities | Khas (Bahun, Chhetri, Khas Nepali), Magar, Newar, Gurung |

| • Religions | Hinduism, Buddhism |

| Time zone | NST (UTC+5:45) |

| Postal Code | 33700 (WRPD), 33702, 33704, 33706, 33708, 33713 |

| Area code(s) | 061 |

| Website |

pokharamun |

Pokhara (Nepali: पोखरा) is a sub-metropolitan and the second largest city of Nepal as well as the headquarters of Kaski District, Gandaki Zone and the Western Development Region. It is located 200 kilometres (120 miles) west of the capital Kathmandu. Despite being a comparatively smaller valley than Kathmandu, its geography varies dramatically within just few kilometres from north to south. The altitude varies from 827 metres (2,713 feet) in the southern part to 1,740 metres (5,710 feet) in the north.[1] Additionally, the Annapurna Range with three out of the ten highest mountains in the world — Dhaulagiri, Annapurna I and Manaslu — are within approximately 15 – 35 miles of the valley.[2][3][4] Due to its proximity to the Annapurna mountain range, the city is also a base for trekkers undertaking the Annapurna Circuit through the ACAP region[5] of the Annapurna ranges in the Himalayas.

Pokhara is home to many Gurkha soldiers. It is the most expensive city in the country, with a cost-of-living index of 150, and the most expensive place in Nepal after Namche Bazaar.

Geography

Pokhara is in the northwestern corner of the Pokhara Valley,[6] which is a widening of the Seti Gandaki valley that lies in the midland region (Pahad) of the Himalayas. In this region the mountains rise very quickly,[7] and within 30 kilometres (19 miles), the elevation rises from 1,000 to 7,500 metres (3,300 to 24,600 feet). As a result of this sharp rise in altitude the area of Pokhara has one of the highest precipitation rates in the country (3,350 mm/year or 131 inches/year in the valley to 5600 mm/year or 222 inches/year in Lumle).[8] Even within the city there is a noticeable difference in rainfall between the south and the north: The northern part at the foothills of the mountains experiences a proportionally higher amount of precipitation.

The Seti Gandaki is the main river flowing through the city.[9] The Seti Gandaki (White River) and its tributaries have created several gorges and canyons in and around Pokhara that gives intriguingly long sections of terrace features to the city and surrounding areas. These long sections of terraces are interrupted by gorges that are hundreds of meters deep.[10] The Seti gorge runs through Pokhara from north to south and then west to east; at places these gorges are only a few metres wide. In the north and south, the canyons are wider.[11]

In the south, the city borders Phewa Tal (4.4 km2) at an elevation of about 827 metres (2,713 feet) above sea level and Lumle at 1,740 metres (5,710 feet) in the north of the touches the base of the Annapurna mountain range. Pokhara, the city of lakes, is the second largest city of Nepal after Kathmandu. Three 8,000-metre (26,000-foot) peaks (Dhaulagiri, Annapurna, Manaslu) can be seen from the city.[12] The Machhapuchhre (Fishtail) with an elevation of 6,993 metres (22,943 feet) is the closest to the city.[13]

The porous underground of the Pokhara valley favours the formation of caves and several caves can be found in the city limits. In the south of the city, a tributary of the Seti flowing out of the Phewa Lake disappears at Patale Chhango (पाताले छाँगो, Nepali for Hell's Falls, also called Davis Falls, after someone who supposedly fell in) into an underground gorge, to reappear 500 metres (1,600 feet) further south.[14][15] To the southeast of Pokhara is the municipality of Lekhnath, a recently established town in the Pokhara valley, home to Begnas Lake.[16]

Climate

The city has a humid subtropical climate; however, the elevation keeps temperatures moderate. Summer temperatures average between 25 and 33 °C, in winter around - 2 to 15 °C. Pokhara and nearby areas receive a high amount of precipitation. Lumle, 25 miles from the Pokhara city center, receives the highest amount of rainfall (> 5600 mm/year or 222 inches/year) in the country.[17] Snowfall is not observed in the valley, but surrounding hills experience occasional snowfall in the winter. Summers are humid and mild; most precipitation occurs during the monsoon season (July - September). Winter and spring skies are generally clear and sunny.[18] The highest temperature ever recorded in Pokhara was 38.5 °C (101.3 °F) on the 4th May 2013, while the lowest temperature ever recorded was 0.5 °C (32.9 °F) on the 13th January 2012 .[19]

| Climate data for Pokhara (1981-2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 19.7 (67.5) |

22.2 (72) |

26.7 (80.1) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.1 (86.2) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.0 (86) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.3 (84.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

26.7 (80.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 13.4 (56.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

19.8 (67.6) |

22.8 (73) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.1 (79) |

25.1 (77.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

21.1 (70) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.8 (55) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

20.8 (69.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.9 (53.4) |

8 (46) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 23 (0.91) |

35 (1.38) |

60 (2.36) |

128 (5.04) |

359 (14.13) |

669 (26.34) |

940 (37.01) |

866 (34.09) |

641 (25.24) |

140 (5.51) |

18 (0.71) |

22 (0.87) |

3,901 (153.58) |

| Source: Sistema de Clasificación Bioclimática Mundial[20] | |||||||||||||

History

Pokhara lies on an important old trading route between China and India. In the 17th century it was part of the Kingdom of Kaski which was one of the Chaubise Rajya (24 Kingdoms of Nepal, चौबिसे राज्य) ruled by a branch of the Shah Dynasty. Many of the hills around Pokhara still have medieval ruins from this time. In 1786 Prithvi Narayan Shah added Pokhara into his kingdom. It had by then become an important trading place on the routes from Kathmandu to Jumla and from India to Tibet.[21]

Pokhara was envisioned as a commercial center by the King of Kaski in the mid 18th century A.D.[22] when Newars of Bhaktapur migrated to Pokhara, upon being invited by the king, and settled near main business locations such as Bindhyabasini temple, Nalakomukh and Bhairab Tole. Most of the Pokhara, at the time, was largely inhabited by Khas[23] (Brahmin, Chhetri, Thakuri and Dalits), the major communities were located in Parsyang, Malepatan, Pardi and Harichowk areas of modern Pokhara and the Majhi community near the Phewa Lake.[24] The establishment of a British recruitment camp brought larger Magar and Gurung communities to Pokhara.[25] At present the Khas, Gurung (Tamu) and Magar form the dominant community of Pokhara. There is also a sizeable Newari population in the city.[26] A small Muslim community is located on eastern fringes of Pokhara generally called Miya Patan. Batulechaur in the far north of Pokhara is home to the Gandharvas or Gaaineys (the tribe of the musicians).[27]

The nearby hill villages around Pokhara are a mixed community of Khas and Gurung.[28] Small Magar communities are also present mostly in the southern outlying hills. Newar community is almost non-existent in the villages of outlying hills outside the Pokhara city limits.

From 1959 to 1962 approximately 300,000 exiles entered Nepal from neighbouring Tibet following its annexation by China. Most of the Tibetan exiles then sought asylum in Dharamshala and other Tibetan exile communities in India. According to UNHCR, since 1989, approximately 2500 Tibetans cross the border into Nepal each year,[29] many of whom arrive in Pokhara typically as a transit to Tibetan exile communities in India. About 50,000 - 60,000 Tibetan exiles reside in Nepal, and approximately 20,000 of the exiled Tibetans live in one of the 12 consolidated camps, 8 in Kathmandu and 4 in and around Pokhara. The four Tibetan settlements in Pokhara are Jampaling, Paljorling, Tashi Ling, and Tashi Palkhel. These camps have evolved into well-built settlements, each with a gompa (Buddhist monastery), chorten and its particular architecture, and Tibetans have become a visible minority in the city.[30]

Until the end of the 1960s the town was only accessible by foot and it was considered even more a mystical place than Kathmandu. The first road was completed in 1968 (Siddhartha Highway)[31] after which tourism set in and the city grew rapidly.[32] The area along the Phewa lake, called Lake Side, has developed into one of the major tourism hubs of Nepal.[33]

Temples, gumbas and churches

There are numerous temples and gumbas in and around pokhara valley. Many temples serve as combined places of worship for Hindus and Buddhists.[34][35] Some of the popular temples and gumbas are:

- Tal Barahi Temple (located on the island in the middle of Phewa Lake)

- Bindhyabasini Temple

- Sitaladevi Temple

- Mudula Karki Kulayan Mandir

- Sunpadeli Temple(Kaseri)

- Bhadrakali Temple

- Kumari Temple

- Akalaa Temple

- Kedareshwar Mahadev Mani Temple

- Matepani Gumba

- World peace pagoda

- Akaladevi Temple

- Monastery (Hemja)

- Nepal Christiya Ramghat Church, established in 1952 (2009 BS), in Ramghat area of Pokhara is also the first church in Nepal.[36]

Location

The municipality of Pokhara spans 12 kilometres (7.5 miles) from north to south and 6 kilometres (3.7 miles) from east to west but, unlike the capital Kathmandu, it is quite loosely built up and still has much green space.[37] The valley is approximately divided into four to Six parts by the rivers Seti, Bijayapur, Bagadi, Fusre and Hemja. The Seti Gandaki flowing through the city from north to south divides the city roughly in two halves with the business area of Chipledunga in the middle, the old town centre of Bagar in the north and the tourist district of Lakeside (Baidam) to the south all lying on the western side of the river.[38] The gorge through which the river flows is crossed at five places: K.I. Singh Pul, Mahendra Pul and Prithvi Highway Pul from north to south of the city. The floor of the valley is plain, resembles Terai due to its gravel-like surface, and has slanted orientation from northwest to southeast. The city is surrounded by the hills[39] overlooking the entire valley.

Phewa Lake was slightly enlarged by damming which poses a risk of silting up due of the inflow during the monsoon.[40] The outflowing water is partially used for hydropower generation.[41] The dam collapsed in 1974 which resulted in draining of its water and exposing the land leading to illegal land encroachment; since then the dam has been rebuilt.[42] The power plant is about 100 metres (330 feet) below at the bottom of the Phusre Khola gorge. Water from Phewa is diverted for irrigation into the southern Pokhara valley. The eastern Pokhara Valley receives irrigation water through a canal running from a reservoir by the Seti in the north of the city. Some parts of Phewa lake are used as commercial cage fisheries. The lake is currently being encroached upon by invasive water hyacinth (जलकुम्भी झार).[43]

Pokhara is known to be a popular tourist destination.[44][45] The tourist district is along the north shore of the Phewa lake (Baidam, Lakeside and Damside). It is mainly made up of small shops, non-star tourist hotels, restaurants and bars. Most upscale and starred hotels are on the southern shore of the Phewa Lake and southeastern fringes of the city where there are more open lands and unhindered view of the surrounding mountains. Most of the tourists visiting Pokhara trek to the Annapurna Base Camp and Mustang. To the east of the Pokhara valley, in Lekhnath municipality, there are seven smaller lakes such as Begnas Lake,Rupa Lake,Khaste lake, Maidi lake, Neureni lake, Dipang lake. Begnas Lake is known for its fishery projects.[46]

Tourism and economy

After the occupation of Tibet by China in 1950 and the Indo-China war in 1962, the old trading route to India from Tibet through Pokhara became defunct. Today only a few caravans from Mustang arrive in Bagar.

In recent decades, Pokhara has become a major tourist destination: It is considered the tourism capital of Nepal[47] in South Asia mainly for adventure tourism and the base for the famous Annapurna Circuit trek. Thus, a major contribution to the local economy comes from the tourism and hospitalities industry. Many tourists visit Pokhara. Tourism is a major source of income for local people and the city.[48] There are two 5-star hotels and approximately 305 other hotels that includes five 3-star, fifteen 2-star and non-star hotels in the city.[49]

Many medieval era temples (Barahi temple, Bindhyabasini, Bhadrakali, Talbarahi, Guheshwori, Sitaldevi, Gita mandir temple, Bhimsen temple) and old Newari houses are part of the city (Bagar, Bindhyabasini, Bhadrakali, Bhairab Tol, etc.). The modern commercial city centres are at Chipledhunga, New Road, Prithvi Chowk and Mahendrapul (recently renamed as Bhimsen Chowk).

The city promotes two major hilltops as viewpoints to see the city and surrounding panorama, World Peace Pagoda built in 1996 across the southern shore of Phewa lake and Sarangkot which is northwest of the city. In February 2004, International Mountain Museum (IMM)[50] was opened for public in Ratopahiro to boost the city's tourism attractions. Other museums are Pokhara Regional Museum; an ethnographic museum; Annapurna Natural History Museum[51] which houses preserved specimens of flora and fauna, and contains particularly extensive collection of the butterflies, found in the Western and ACAP region of Nepal; and Gurkha Museum featuring history of the Gurkha soldiers.[52]

The city has recently been adorned with a bungee jumping site (the second in Nepal): Water Touch Bunjee Jumping.[53] A cable car service has begun construction joining Fewa Lake with World Peace Stupa led by the government of Nepal which is expected to boost the tourism exponentially.[54]

Since the 1990s Pokhara has experienced rapid urbanization. As a result, service-sector industries have increasingly contributed to the local economy[55] overtaking the traditional agriculture. An effect of urbanization is seen in high real estate prices, among the highest in the country.[56][57] The major contributors to the economy of Pokhara are manufacturing and service sector including tourism; agriculture and the foreign and domestic remittances. Tourism, service sector and manufacturing contributes approximately 58% to the economy, remittances about 20% and agriculture nearly 16%.[58]

Arrivals

| Year | Number of international tourists arriving in Pokhara[59] | % |

|---|---|---|

| Year | Foreign tourists | % Change from previous year |

| 1995 | 363,395 | - |

| 1996 | 393,613 | 8.3 |

| 1997 | 421,857 | 7.2 |

| 1998 | 463,684 | 9.9 |

| 1999 | 491,504 | 6.0 |

| 2000 | 463,646 | -5.7 |

| 2001 | 77,853 | -84 |

| 2002 | 68,056 | -23.7 |

| 2003 | 85,529 | 22.7 |

| 2004 | 87,693 | 13.9 |

| 2005 | 74,012 | |

| 2006 | 94,799 | |

| 2007 | 165,177 | 74 |

| 2008 | 186,643 | |

| 2009 | 203,527[60] | 5 |

| 2010 | 230,799[61] | 13.39 |

| 2011 | [62] | |

| 2012 | [59] | |

| 2013 | [63] |

Hotels and lodges

There are more than 250[64] tourist category hotels and lodges in Pokhara of which two (the Fulbari Resort and Pokhara Grande) are ranked 5-star. Pokhara provides lodging and fooding from backpackers to deluxe ranges.

Trekking agencies

Pokhara is the major tourism Hub in Nepal. Tourism plays a vital role in Pokhara since thousands of tourists visit Pokhara every year and majority of people are involved in the tourism sector. There are many trekking agencies in Pokhara that provide several trekking programs and itineraries for the tourists. Some of the major trekking regions are Annapurna region, Everest region, Langtang region, Manaslu region, Rara/Jumla region and Kanchanjanga/ Makalu region. One of the oldest trekking agencies in Pokhara is Sisne Rover Trekking located in Lakeside that has been serving its customers since 25 years. Similarly, many other trekking agencies are available to help make the trekking experience remarkable and enjoyable.

Military

Pokhara region has a very strong military traditions with significant number of its men being employed by the Nepali army.[65] The Western Division HQ[66] of the Nepalese Army is stationed at Bijayapur, Pokhara and its Area of Responsibility (AOR) consists of the entire Western Development Region of Nepal. The AOR of this Division is 29,398 km2 and a total of 16 districts are under the Division. The population of the AOR of Western Division is 4,571,013. Both British Army and the Indian Army have regional recruitment and pensioners facilitation camps in Pokhara. The British Gurkha Camp[67] is located at Deep Heights in the northeast of the Pokhara city and the Indian Gorkha Pension Camp[68] is in the south-western side of the city, Rambazar.

Education

Education in Pokhara is considered the best after Kathmandu. There are a number of medical, engineering, forestry, IT related colleges and institutions and so on. Some of which are here:

- SOS Hermann Gmeiner School, Gandaki

- Shree Bhadrakali Higher Secondary School

- Prativa higher secondary school

- IOE Western Region Campus

- Amarsingh Model Higher Secondary School

- Gandaki Boarding School

- Saraswati Adarsha Vidhyashram

- Alpha Boarding School

- Pragati English Boarding School

- Lotus Academic School

- Tarakunja Boarding School

- Step By Step Higher Secondary School.

- Sagarmatha Higher Secondary School

- Tops English Boarding School.

- Janapriya Multiple campus (JMC)

- Janapriya Higher Secondary School

- Gandaki College of Engineering and Science,[69]

- Pokhara Engineering College,[70]

- Institute of Forestry - Pokhara Campus,[71]

- Pokhara Nursing Campus affiliated to the Tribhuvan University[72]

- Manipal College of Medical Science[73] affiliated to Kathmandu University

- Himanchal Boarding School

- Kantipur Dental College (KIHS)

- Gandaki Medical College

- Mount Annapurna School

- Global Collegiate Higher Secondary School

- Bal Mandir Higher Secondary School

- Srijana Higher Secondary School

Hospitals

Some of the hospitals in Pokhara are:

- Fewa City Hospital

- Fishtail Hospital

- Gandaki Regional Hospital

- Manipal Teaching Hospital

- Gandaki Medical Collage

- Himalaya Eye Hospital

- Padhma Nursing Home

- B.G Hospital

- Kaski Sewa Hospital

- Metro City Hospital

- OM Hospital

- kaski sewa Hospital

- Lake City Hospital And Critical Care Pvt.Ltd

- Namaste Hospital

Non-governmental organizations

Transportation

Public transit

Pokhara has extensive privately operated public transportation system running throughout the city, adjoining townships and nearby villages. The public transport mainly consists of local and city buses, micros, micro-buses and metered-taxis.[74]

Intercity connections

Pokhara is well connected to rest of the country through permanent road and air links. The main mode of transportation are public buses and the Purano Bus Park is the main hub for buses plying country wide. The all-season Pokhara Airport with regular flights to Kathmandu, Mustang are operated by various domestic and a few international airlines. A new international airport is being constructed in the southeast of the city.[75] Flight duration from Kathmandu to Pokhara is approximately 30 minutes.[76]

Rivers and lakes

Pokhara valley is rich in water sources. The major bodies of water in and around Pokhara are:[77][78]

Lakes

- Phewa Lake

- Begnas Lake

- Rupa Lake

- Dipang Tal

- Khoste Tal

- Maidi Tal

- Niureni Tal

- Gude Tal

- Kamal Pokhari Tal

Rivers

- Seti Gandaki (Seti Khola)

- Kahun Khola

- Bijaypur Khola

- Furse Khola

- Kali Khola

- Yamdi Khola

- Mardi Khola

Sports

The sporting activities are mainly centered in the multipurpose stadium Pokhara Rangasala (or Annapurna Stadium) in Rambazar. The popular sports are football, cricket, volleyball, basketball etc. The Sahara Club is one of the most active organizations promoting football in the city and organizes a South Asian club-level annual tournament: the Aaha Gold Cup.[79] Additionally, the Kaski District Football Association (KDFA) organizes Safal Pokhara Gold Cup,[80] which is also a South Asian club-level tournament and ANFA organizes local Kaski district club-level Balram KC memorial football tournament.[81] B-13,Sangam & LG are the power house Football club in Pokhara. There are several tennis courts and a golf course[82] in the city. Nearby Sarangkot hill has developed as a good attraction for adventure activities such as paragliding[83] and skydiving.[84] The Pokhara city marathon, high altitude marathon are some activities attracting mass participation.[85] Adventure sports such as base jumping, paragliding, canyoning, rock climbing, bungee jumping, etc. are targeted towards tourists.[86][87][88]

Music

The universal instruments used in Nepalese music include the madal (small leather drum), bansuri (bamboo flute), and saarangi. These instruments are prominent features of the traditional folk music (lok gít or lok geet) in Pokhara, which is actually the western (Gandaki, Dhaulagiri and Lumbini) branch of Nepali lok geet. Some examples of the music of this region are Resham Firiri (रेशम फिरिरी)[89] and Khyalee Tune (ख्याली धुन).[90] The lok geet started airing in Radio Nepal during the 1950s and artists such as Jhalakman Gandharva, Dharma Raj Thapa are considered pioneers in bringing the lok git into mass media. During early and late 1990s, bands from Pokhara like Nepathya started their very successful fusion of western rock and pop with traditional folk music.[91] Since then several other musical groups in Nepal have adopted the lok-pop/rock style producing dozens of albums every year. Another important part of cultural music of western Nepal, and hence Pokhara, is the Panché Baaja (पञ्चे बाजा), a traditional musical band performed generally during marriage ceremonies by the damaai musicians.[92] The musical culture in Pokhara is quite dynamic and in recent years, Western rock and roll, pop, rap and hip-hop are becoming increasingly popular with frequently held musical concerts; however, the traditional lok and modern (semiclassical) Nepali music are predominantly favored by the general populace. More musical concerts are held in Pokhara than in any other city in the country.[93][94]

Media and communications

Media and communication were quite limited until the 1990s.[95] However, in the following decade there has been a proliferation of private media in print, radio and television. There are 18 privately owned local FM stations in Pokhara valley; 102.6- Radio Apostle 93.4 - Annapurna 94.6- 3 angels 90.6 janani 91.0 - macchhapucchhre 91.8 - entertainment 93.8 - sarangi 99.2 - barahai 100.0 - radio Nepal 104.6 sarangkot 106.6 - lekhnath 95.4 - mega 101.2 - big 101.8 - kantipur 102.2 - Safalta 88.2 - national 105.6 - city 107.6- taranga

An additional 4 FM stations from Kathmandu have their relay broadcast stations in Pokhara, making a total of 22 FM stations.[96] Among them there are six Community radio Stations, They are Himchuli FM - 92.2 MHz, Gorkhali Radio -106 MHz, Samudayik, Radio Sunaulo F.M - 107.2 MHz and Radio Gandaki 90.2 MHZ, Radio Hemja 88.5 MHz. There are four local television stations: GoldenEye Television, Pokhara Television,Gandaki Television and fewa television. Approximately 14 national daily newspapers, in Nepali are published in the city[97][98][99] along with several other weekly and monthly news magazines. All major national newspapers published in Kathmandu have distributions in Pokhara. A number of online news and entertainment-based websites are also based in Pokhara.[100][101] Popular technology based web-magazine TechSansar also started from Pokhara city.[102] Pokhara has got 3G networks of both Nepal Telecom and Ncell. Majority of the people in the city access internet through mobiles, numerous cyber cafes and local wireless ISPs. Most tourist restaurants and hotels also provide WiFi services. Wi-Fi hotspot by Nepal Telecom using Wi-MAX technology,[103] started in Feb. 2014, is accessible in most parts of the city for a fee.[104][105] Subscriber based internet is provided by several private ISP providers in Pokhara namely Worldlink, Pokhara Internet, Subisu, Websurfer, Radius Communication.[106]

See also

References

- ↑ Earthquake Risk Reduction and Recovery Preparedness Programme for Nepal: UNDP/ERRRP – Project Nep/07/010 (July 2009). "Report on Impact of Settlement Pattern, Land Use Practice and Options in High Risk Areas: Pokhara Sub‐Metropolitan City" (PDF). Kathmandu: UNDP, Nepal. p. 10.

- ↑ "Mardi Himal trek & climb". Annapurna Encounter Pvt. Ltd.

- ↑ United Nations Field Coordination Office (UNFCO) (7 June 2011). "An Overview of the Western Development Region of Nepal" (PDF). Bharatpur, Nepal: United Nations: Nepal Information Platform. pp. 1–9.

- ↑ Pradhan, Pushkar Kumar (1982). "A Study of Traffic Flow on Siddartha and Prithvi Highway". The Himalayan Review. 14: 38–51. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013.

- ↑ Holden, Andrew; Sparrowhawk, John (2002). "Understanding the motivations of ecotourists: the case of trekkers in Annapurna, Nepal". International Journal of Tourism Research. 4 (6): 435–446. doi:10.1002/jtr.402. ISSN 1522-1970.

- ↑ Gurung, Harka B. (2001). Pokhara Valley: A Geographical Survey. Kathmandu, Nepal: Nepal Geographical Society.

- ↑ Joshi, S. C.; Haigh, M. J.; Pangtey, Y. P. S.; Joshi, D. R.; Dani, D. D. (1986). Joshi, S. C, ed. Nepal Himalaya: geo-ecological perspectives. Naini Tal, India: Himalayan Research Group. pp. 78–80.

- ↑ Bezruchka, Stephen; Lyons, Alonzo (2011). Trekking Nepal: A Traveler's Guide (8th ed.). Seattle, Washington, USA: The Mountaineers Books. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-89886-613-1.

- ↑ Tripathi, M. P.; Singh, S. B. (1996). "Histogenesis and Functional Characteristics of Pokhara, Nepal". New Perspectives in Urban Geography. New Delhi, India: M D Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 51–60. ISBN 81-7533-014-7.

- ↑ Fort, Monique (2010). "The Pokhara Valley: A Product of a Natural Catastrophe". In Piotr Migoń. Geomorphological Landscapes of the World. London: Springer. pp. 265–274. ISBN 978-90-481-3054-2.

- ↑ Paudel, Lalu Prasad; Arita, Kazunori (April 2000). "Tectonic and polymetamorphic history of the Lesser Himalaya in central Nepal". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 18 (5): 561–584. doi:10.1016/S1367-9120(99)00069-3. ISSN 1367-9120.

- ↑ Herzog, Maurice (1952). Annapurna: The First Conquest of an 8,000-meter Peak (Kindle Edition in 2011 ed.). New York, NY, USA: E. P. Dutton & Co. Inc. ISBN 978-1-4532-2073-3.

- ↑ Negi, S. S. (1998). "Geographical Profile". Discovering the Himalaya. New Delhi, India: Indus Publishing Company. pp. 9–55. ISBN 81-7387-079-9.

- ↑ Gautam, Pitamber; Pant, Surendra Raj; Ando, Hisao (July 2000). "Mapping of subsurface karst structure with gamma ray and electrical resistivity profiles: a case study from Pokhara valley, central Nepal". Journal of Applied Geophysics. 45 (2): 97–110. doi:10.1016/S0926-9851(00)00022-7. ISSN 0926-9851.

- ↑ Thapa, Netra Bahadur; Thapa, D. P. (1969). Geography of Nepal: physical, economic, cultural & regional. Bombay, India: Orient Longmans. p. 186.

- ↑ Thapa, L. B (23–29 April 2007). "Ailing valley" (PDF). Newsfront. Kathmandu, Nepal. p. 7.

- ↑ Kansakar, Sunil R; Hannah, David M.; Gerrard, John; Rees, Gwyn (2004). "Spatial pattern in the precipitation regime of Nepal". International Journal of Climatology. 24 (13): 1645–1659. doi:10.1002/joc.1098. ISSN 1097-0088.

- ↑ Taylor, Chris (1998–1999). "The High Mountain Valleys and Passes". Traveler's Companion Nepal. France: Allan Amsel Publishing. pp. 184–190. ISBN 0-7627-0231-1.

- ↑ . Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ NEPAL-POKHARA AIRPORT. Centro de Investigaciones Fitosociológicas. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ↑ Furer-Haimendorf, Christoph von (1978). "Trans-Himalayan Traders in Transition". In Fisher, James F. Himalayan Anthropology. Great Britain: Mouton Publishers. p. 339. ISBN 90-279-7700-3.

- ↑ Blaikie, P. M.; Cameron, John; Seddon, John Davis (2005). "The Growth of Towns in West-Central Nepal". Nepal in Crisis: Growth and Stagnation at the Periphery. New Delhi, India: Adroit Publishers. pp. Chapter 6. ISBN 81-87392-19-3.

- ↑ Onta, Pratyoush; Liechty, Mark; Tama, Seira (December 2005). "Studies in Nepali History and Society" (PDF). 10 (2). Mandala Book Point, Kathmandu: Centre for Social Research and Development, Nepal Studies Group: 290. ISSN 1025-5109.

- ↑ Whelpton, John (2005). A History of Nepal. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80026-9.

- ↑ Ragsdale, Tod Anthony (1989). Once a hermit kingdom: ethnicity, education and national integration in Nepal. Kathmandu: Manohar Publ. ISBN 81-85054-75-4.

- ↑ Genetti, Carol (2007). "Context: The distribution of Newars throughout Nepal". A Grammar of Dolakha Newar. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, GmbH & Co., KG. p. 12. ISBN 978-3-11-019303-9.

- ↑ Adhikari, Jagannath; Seddon, David (2002). Pokhara: biography of a town. Kathmandu, Nepal: Mandala Publications. ISBN 999331014X.

- ↑ Ragsdale, Tod A. (January 1990). "Gurung, Gorkhalis, Gurkhas: Speculations on a Nepalese Ethno-History" (PDF). CNAS Journal. Contributions to Nepalese Studies (CNAS), Tribhuvan University. 17 (1): 1–24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2013.

- ↑ Frechette, Ann (2002). Tibetans in Nepal: The Dynamics of International Assistance Among a Community in Exile (Studies in forced Migration - Vol. 11 ed.). USA: Berghahn Books. p. 136. ISBN 1-57181-157-5.

- ↑ Chhetri, Ram, B. (July 1990). "Adaptation of Tibetan Refugees in Pokhara, Nepal: A Study on Persistence and Change". Theses for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (University of Hawaii at Manoa) no. 2542.

- ↑ Regmi Research Project (1979). Nepal Press Digest (Vol. 20, Issue 20 ed.). Regmi Research (Private) Ltd. p. 13.

- ↑ Bindloss, Joe; Holden, Trent; Mayhew, Bradley (2009). Nepal (8th ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Lonely Planet Publications. pp. 235–270. ISBN 9781741048322.

- ↑ Sharma, Pitamber (2000). "Phewa Lakeside: Problems of tourism and common property resources". Tourism as Development: Case Studies from the Himalaya. Kathmandu: Himal Books. p. 53. ISBN 99933-13-00-9.

- ↑ Boke, Charis (2008). "Faithful Leisure, Faithful Work: Religious Practice as an Act of Consumption in Nepal". Himalayan Research Papers Archive: 1–21.

- ↑ Adhikari, Jagannath (2004). "A socio-ecological analysis of 'the loss of public properties in an urban environivient: a case study of Pokhara, Nepal" (PDF). Contributions to Nepalese Studies. 31 (1): 85–114.

- ↑ Barclay, John (2009). "The Church in Nepal: Analysis of its Gestation and Growth". International Bulletin of Missionary Research. 33 (4): 189–194. ISSN 0272-6122.

- ↑ Poudel, Khagendra Raj (27–30 January 2008). Peskova, Katerina, ed. Urban Growth and Land Use Change in the Himalayan Region: A Case Study of Pokhara Metropolitan City, Nepal (PDF). Ostrava, Czech Republic: 15th year of International Symposium GIS Ostrava 2008 proceedings, VSB - Technical University of Ostrava. ISBN 978-80-254-1340-1.

- ↑ Nakanishi, Masami; Watanabe, M. M.; Terashima, A.; Sako, Y.; Konda, T.; Shrestha, K.; Bhandary, H. K.; Ishida, Y. (1988). "Studies on Some Limnological Variables in Subtropical Lakes of the Pokhara Valley, Nepal". Japanese Journal of Limnology. 49 (2): 71–86. doi:10.3739/rikusui.49.71. ISSN 0021-5104. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ Childress, David Hatcher (1998). Lost Cities of China, Central Asia and India. Kempton, IL, USA: Adventures Unlimited Press. pp. 43–84. ISBN 0-932813-07-0.

- ↑ Ross, Jamie; Gilbert, Robert (February 1999). "Lacustrine sedimentation in a monsoon environment: the record from Phewa Tal, middle mountain region of Nepal". Geomorphology. 27 (3-4): 307–323. doi:10.1016/S0169-555X(98)00079-8. ISSN 0169-555X. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ Rai, Ash Kumar (2008). "Environmental Impact from River Damming for Hydroelectric Power Generation and Means of Mitigation" (PDF). Hydro Nepal. Journal of Water, Energy and Environment. 1 (2): 22–25. ISSN 1998-5452.

- ↑ Pokharel, Shailendra (2008). "Conservation of Phewa Lake of Pokhara, Nepal" (PDF). The Research Center for Sustainability and Environment, Shiga University. Grant-in-Aid project for Promotion of Special Education Research by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

- ↑ Shrestha, M. K.; Batajoo, R. K.; Karki, G. B. (2002). "Prospects of fisheries enhancement and aquaculture in lakes and reservoirs of nepal". In Petr, T.; Swar, D. B. Cold Water Fisheries in the Trans-Himalayan Countries. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome: FAO Fisheries Technical Papers 431. p. 289. ISBN 92-5-104807-X.

- ↑ Hall, C. Michael; Page, Stephen (2011). "18: Tourism in Nepal, Bhutan and Tibet: contrasts in the facilitation, constraining and control of tourism in the Himalayas - Nepal". Tourism in South and South East Asia: Issues and Cases. New York: Routledge. pp. 256–264. ISBN 9780750641289.

- ↑ Kantipur News Service (1 January 2014). "Pokhara tourism expects 2014 to herald new era of growth". Kantipur.

- ↑ Rai, Ash Kumar (2000). "Evaluation of natural food for planktivorous fish in Lakes Phewa, Begnas, and Rupa in Pokhara Valley, Nepal". Limnology. 1 (2): 81–89. doi:10.1007/s102010070014.

- ↑ Nepal, S. K.; Kohler, T.; Banzhaf, B. R. (2002). Great Himalaya: tourism and the dynamics of change in Nepal. Zürich, Switzerland: Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research. ISBN 3-85515-106-7.

- ↑ Zurick, David N. (1992). "Adventure Travel and Sustainable Tourism in the Peripheral Economy of Nepal". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 82 (4): 608–628. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1992.tb01720.x.

- ↑ Adhikari, Bimal (2011). "Tourism Strategy of Nepalese Government And Tourist's Purpose of Visit in Nepal". Aichi Shukutoku Knowledge Archive. 7: 79–94. ISSN 1881-0373.

- ↑ Himalayan News Service (18 December 2011). "Pokhara gets another key attraction". The Himalayan Times. Kathmandu.

- ↑ Smith, Colin (1989). Butterflies of Nepal (Central Himalaya): a colour field guide including all the 614 species recorded up-to-date. Bangkok, Thailand: Tecpress Service. p. 351. ISBN 9789748684932.

- ↑ Official Website. "The Gurkha Memorial Museum". Gurkha Memorial Museum Nepal.

- ↑ Sapkota, Sagun. "Water Touch Bunjee, Pokhara". www.livelitt.com. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ Sapkota, Sagun. "Pokhara gets new cable car at long last.". Tourist Nepal.

- ↑ Thapa, Ram Bahadur (2004). "Financial Resource Mobilization in Pokhara Municipal Corporation". Journal of Nepalese Business Studies. 1 (1): 81–84. doi:10.3126/jnbs.v1i1.42.

- ↑ Piipuu, Merilin (10 September 2014). "Pokhara tries to save its famous paddy" (723). Nepali Times.

- ↑ Himalayan News Service (17 May 2013). "Project Pokhara". The Himalayan Times.

- ↑ Baniya, Lal Bahadur (2004). "Human Resource Development Practice in Nepalese Business Organizations: A Case Study of Manufacturing Enterprises in Pokhara". Journal of Nepalese Business Studies. 1 (1): 58–68. doi:10.3126/jnbs.v1i1.39.

- 1 2 Ghimire, Bal Krishna (Chief Editor) (2013). "Nepal Tourism Statistics 2012" (PDF). http://www.tourism.gov.np/. Kathmandu: Ministry of Culture, Tourism & Civil Aviation. Govt. of Nepal. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Sharma, Lal Prasad (30 October 2010). "Tourist arrivals in Pokhara swell 20pc". The Kathmandu Post.

- ↑ Pokhrel, Santosh (8 March 2011). "Tourist arrivals to Pokhara up". Republica.

- ↑ eTN (2 January 2012). "Nepal tourism misses 1 million arrivals target". eTN Global Travel Industry News.

- ↑ TravelBizNews (8 March 2014). "798,000 tourists visited Nepal in 2013,arrivals down by 0.7 %". TravelBizNews Online.

- ↑ Sedai, Ram Chandra (2011). "Tourist Accommodation Facilities in the major Tourist Areas of Nepal". Nepal Tourism and Development Review. 1 (1): 102–123. doi:10.3126/ntdr.v1i1.7374.

- ↑ Heide, Susanne von der; Hoffman, Thomas (2001). Aspects of Migration and Mobility in Nepal. Portland, OR, USA: Hawthorne Blvd Books. ISBN 9993303615.

- ↑ Official Website, Nepalese Army. "Western Division". Kathmandu: Nepalese Army (नेपाली सेना).

- ↑ Official Website, Brigade of Gurkhas. "British Gurkhas Recruiting". UK: British Army. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012.

- ↑ Official Website. "Pension Paying Office at Pokhara". India: Indian Embassy, Nepal. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011.

- ↑ Official Website. "Gandaki College of Engineering and Science".

- ↑ Official Website. "Pokhara Engineering College".

- ↑ Official Website. "Institute of Forestry - Pokhara Campus". Institute of Forestry, Tribhuvan University.

- ↑ Official Website. "Institute of Medicine". IOM, Tribhuvan University.

- ↑ Shankar, P. Ravi, MD (15 October 2007). "Pokhara – a 'Different' Setting for Medical Education". Journal of Medical Sciences Research. 1 (1): 63–64. ISSN 1938-5765.

- ↑ "Getting Around". Pokhara Web Directory.

- ↑ Himalayan News Service (15 October 2011). "Pokhara to have international airport". The Himalayan Times. Kathmandu.

- ↑ "Pokhara Flight (PKR)". Nepal Flight Info. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ↑ Thapa, Gopal B.; Weber, Karl E. (June 1992). "Deforestation in the Upper Pokhara Valley, Nepal". Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography. 12 (1): 52–67. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9493.1991.tb00028.x.

- ↑ Bisht, Ramesh Chandra (2008). International Encyclopaedia of Himalayas (Vol. 4, Nepal Himalayas ed.). Mittal Publications. ISBN 81-8324-269-3.

- ↑ Himalayan News Service (29 January 2012). "Sahara set for Aaha Gold Cup". The Himalayan Times. Kathmandu.

- ↑ Himalayan News Service (24 October 2011). "Safal Pokhara Cup in November". The Himalayan Times. Kathmandu.

- ↑ Republica Sports (26 December 2009). "Pokhara Valley win football tournament". Republica. Kathmandu.

- ↑ "A Golfing High at Pokhara's Himalayan Golf Course". Himalayan Golf Course Pokhara.

- ↑ Goldberg, Kory; Décary, Michelle (2009). "Kathmandu - Pokhara". Along the Path - The Mediator's Companion to the Buddha's Land. Onalaska, WA, USA: Pariyatti Press. pp. 326–329. ISBN 978-1-928706-56-4.

- ↑ Himalayan News Service (1 November 2010). "Pokhara skies offer divers a swell time". The Himalayan Times. Kathmandu.

- ↑ "Annapurna marathon begins Thursday". Republica. Kathmandu, Nepal. 27 April 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ↑ Neupane, Kul Chandra (11 January 2004). "Paragliding lures more tourists to Pokhara". The Kathmandu Post.

- ↑ Sharma, Lal Prasad (8 March 2012). "Pokhara entrepreneurs trying to lure more domestic tourists". e-Kantipur (Kantipur Publications).

- ↑ Sharma, Shiva (22 September 2014). "High Ground introduces bungy jumping in Pokhara" (XXII (216), pp. 13-14). The Kathmandu Post. Kantipur News Service.

- ↑ Gandharva, Tirtha Bd. "Resham Firiri". MetaLab & MusicNepal.

- ↑ Nepali, Ram Sharan. "Khyalee Tune". MetaLab & MusicNepal.

- ↑ Greene, Paul D. (2002–2003). "Nepal's "Lok Pop" Music: Representations of the Folk, Tropes of Memory, and Studio Technologies". Asian Music. 34 (1): 43–65. JSTOR 834421.

- ↑ Tingey, Carol (1994). Auspicious music in a changing society: The Dāmai musicians of Nepal. New Delhi, India: Heritage Publishers. ISBN 8170261937.

- ↑ Acharya, Madhu Raman (2002). Nepal culture shift!: Reinventing Culture in the Himalayan Kingdom. New Delhi, India: Adroit Publishers. ISBN 978-8-18-739226-2.

- ↑ Wallach, Jeremy; Berger, Harris M.; Greene, Paul D. (2011). "Metal and the Nation". Metal Rules the Globe: Heavy Metal Music Around the World. Durham, NC, USA: Duke University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8223-4733-0.

- ↑ Wilmore, Michael (2008). Developing Alternative Media Traditions in Nepal. Langam, MD, USA: Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-2525-7.

- ↑ Lin, Kong Yen; Dixit, Kunda (1–7 May 2009). "Women on air". Nepali Times.

- ↑ "समाचारपाटी डटकम (पोखराबाट संचालित राष्ट्रिय स्तरको अनलाइन पत्रिका)".

- ↑ "आदर्श समाज राष्ट्रिय दैनिक".

- ↑ "समाधान राष्ट्रिय दैनिक".

- ↑ "गन्थन डट कम".

- ↑ Kshetri, Indra Dhoj (2008). "Online News Portals in Nepal: An Overview". Bodhi: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2 (1): 260–267. doi:10.3126/bodhi.v2i1.2876. ISSN 2091-0479.

- ↑ "About TechSansar". About TechSansar. 17 October 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ "List & Location of available NT WiFi Hotspots". TechSansar.com. Retrieved 2016-01-31.

- ↑ Bhuju, Kriti (9 February 2014). "NT offers free Wi-Fi for a month". My Republica. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ Nepal Telecom. "WiMAX : Wireless Broadband Internet Service: List of NT WiFi Hotspots". www.ntc.net.np. Nepal Telecom. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ "Invent Pokhara". Pokhara Web Directory.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pokhara. |

- Open Directory Project entry for Pokhara

- The official Pokhara website

- To/from Pokhara flight schedules

- Photos of sightseeing places around Pokhara Valley