RMS Queen Elizabeth

| RMS Queen Elizabeth at Cherbourg, France, in 1966. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | |

| Name: |

|

| Namesake: | HM Queen Elizabeth, consort of King George VI, The Queen Mother |

| Owner: |

|

| Port of registry: |

Liverpool (1940–1968) Nassau (1970–1972) |

| Route: | Transatlantic |

| Ordered: | 6 October 1936 |

| Builder: |

|

| Yard number: | Hull 552 |

| Way number: | 4 |

| Laid down: | 4 December 1936[1] |

| Launched: | 27 September 1938 |

| Christened: | 27 September 1938 |

| Maiden voyage: | 3 March 1940 |

| Identification: | Radio Callsign GBSS |

| Fate: | Fire-damaged and partially dismantled, vessel's remains covered over on seabed in Hong Kong Harbour in 1975 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage: | 83,673 gross tons |

| Displacement: | 83,000+ tonnes |

| Length: | 1,031 ft (314.2 m) |

| Beam: | 118 ft (36.0 m) |

| Height: | 233 ft (71.0 m) |

| Draught: | 38 ft (11.6 m) |

| Propulsion: | Steam turbine (single reduction gear) |

| Capacity: | 2,283 passengers |

| Crew: | 1,000+ crew |

RMS Queen Elizabeth was an ocean liner operated by the Cunard Line (after its merger with the White Star Line). Along with her sister ship Queen Mary, she provided luxury liner and immigrant service between Southampton in the United Kingdom and New York in the United States, via Cherbourg in France. She was also contracted for over 20 years to carry the Royal Mail, thus enabling her to carry the prestigious Royal Mail Ship (RMS) designation, as the second half of the two ships' weekly express service.

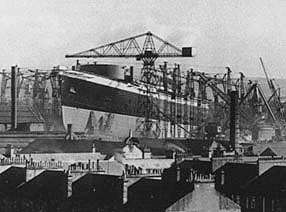

While being constructed in the mid-1930s by John Brown and Company at Clydebank, Scotland, she was known as Hull 552[2] but when launched, on 27 September 1938, she was named in honour of Queen Elizabeth, who was then Queen Consort to King George VI and in 1952 became the Queen Mother. With a design that improved upon that of Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth was a slightly larger ship, the largest passenger liner ever built at that time and for 56 years thereafter. She also has the distinction of being the largest-ever riveted ship by gross tonnage. She first entered service in February 1940 as a troopship in World War II, and it was not until October 1946 that she served in her intended role as an ocean liner.

With the decline in the popularity of the transatlantic route, both ships were replaced by the smaller, more economical Queen Elizabeth 2 in 1969. Queen Mary was retired from service on 9 December 1967, and was sold to the city of Long Beach, California, US. Queen Elizabeth was sold to a succession of buyers, most of whom had adventurous and unsuccessful plans for her. Finally she was sold to a Hong Kong businessman, Tung Chao Yung, who intended to convert her into a floating university cruise ship. In 1972, while undergoing refurbishment in Hong Kong harbour, she caught fire under mysterious circumstances and was capsized by the water used to fight the fire. In 1973, her wreck was deemed an obstruction, and she was partially scrapped where she lay.[3]

Building and design

On the day RMS Queen Mary sailed on her maiden voyage, Cunard's chairman, Sir Percy Bates, informed his ship designers that it was time to start designing the planned second ship known as Hull 552.[4] The official contract between Cunard and government financiers was signed on 6 October 1936.[5]

The new ship improved upon the design of Queen Mary[6] with sufficient changes, including a reduction in the number of boilers to twelve instead of Mary's twenty-four, that the designers could discard one funnel and increase deck, cargo and passenger space. The two funnels were self-supporting and braced internally to give a cleaner looking appearance while the forward well deck was omitted, a more refined hull shape was achieved and a sharper, raked bow was added for a third bow-anchor point.[6] She was to be eleven feet longer and 4,000 tons greater displacement than her older sister ship, Mary.[7][5]

Queen Elizabeth was built on slipway four at John Brown & Company in Clydebank, Scotland. During her construction she was more commonly known by her shipyard number, Hull 552.[8] The interiors were designed by a team of artists headed by the architect George Grey Wornum.[9] Cunard's plan was for the ship to be launched in September 1938, with fitting out intended to be complete for the ship to enter service in the spring of 1940.[5] The Queen herself[6] performed the launching ceremony on 27 September 1938 and the ship was sent for fitting out.[5][6] It was announced that on 23 August 1939 the King and Queen were to visit the ship and tour the engine room and 24 April 1940 was to be the proposed date of her maiden voyage. Due to the outbreak of World War II, these two dates were postponed, and Cunard's plans were shattered.[5]

Queen Elizabeth sat at the fitting-out dock at the shipyard in her Cunard colours until 2 November 1939, when the Ministry of Shipping issued special licences to declare her seaworthy. On 29 December her engines were tested for the first time, running from 0900 to 1600 with the propellers disconnected to monitor her oil and steam operating temperatures and pressures. Two months later Cunard received a letter from Winston Churchill,[10] then First Lord of the Admiralty, ordering the ship to leave Clydeside as soon as possible and "to keep away from the British Isles as long as the order was in force".

Maiden voyage

At the start of World War II, it was decided that Queen Elizabeth was so vital to the war effort that she must not have her movements tracked by German spies operating in the Clydebank area. Therefore, an elaborate ruse was fabricated involving her sailing to Southampton to complete her fitting out.[10] Another factor prompting Queen Elizabeth's departure was the necessity to clear the fitting out berth at the shipyard for the battleship HMS Duke of York,[10] which was in need of its final fitting-out. Only the berth at John Brown could accommodate the King George V-class battleship's needs.

.jpg)

One major factor that limited the ship's secret departure date was that there were only two spring tides that year that would see the water level high enough for Queen Elizabeth to leave the Clydebank shipyard,[10] and German intelligence were aware of this fact. A minimal crew of four hundred were assigned for the trip; most were signed up for a short voyage to Southampton from Aquitania.[10] Parts were shipped to Southampton, and preparations were made to drydock the new liner when she arrived.[10] The names of Brown's shipyard employees were booked to local hotels in Southampton to give a false trail of information and Captain John Townley was appointed as her first master. Townley had previously commanded Aquitania on one voyage, and several of Cunard's smaller vessels before that. Townley and his hastily signed-on crew of four hundred Cunard personnel were told by a Cunard representative before they left to pack for a voyage where they could be away from home for up to six months.[11]

By the beginning of March 1940, Queen Elizabeth was ready for her secret voyage. Her Cunard colours were painted over with battleship grey, and on the morning of 3 March she quietly left her moorings in the Clyde. She proceeded out of the river and sailed further down the coast, where she was met by the King's Messenger,[10] who presented sealed orders directly to the captain. Whilst waiting for the messenger the ship was refuelled; adjustments to the ship's compass and some final testing of equipment were also carried out before she sailed to her secret destination.

Captain Townley discovered that he was to take the untested vessel directly to New York without stopping, without dropping off the Southampton harbour pilot who had embarked on Queen Elizabeth from Clydebank, and to maintain strict radio silence. Later that day at the time when she was due to arrive at Southampton, the city was bombed by the Luftwaffe.[10] After a crossing taking six days, Queen Elizabeth had zigzagged her way across the Atlantic at an average speed of 26 knots, avoiding Germany's U-boats; she arrived safely at New York and found herself moored alongside both Queen Mary and the French Line's Normandie. This would be the only time all three of the world's largest liners would be berthed together.[10]

Captain Townley received two telegrams on his arrival in New York, one from his wife congratulating him and the other from the ship's namesake – Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, who thanked him for safe delivery of the ship that was named for her. The ship was then moored for the first time alongside Queen Mary and was secured so that no one could board her without prior permission. This included port officials.[10] Cunard later issued a statement that it had been decided that, due to the global circumstances, it was best that the new liner was moved to a neutral location and that during that voyage the ship had carried no passengers or cargo.

World War II

Queen Elizabeth left the port of New York on 13 November 1940 for Singapore to receive her troopship conversion.[5] After two stops to refuel and replenish her stores in Trinidad and Cape Town, she arrived in Singapore's Naval Docks where she was fitted with anti-aircraft guns, and her hull repainted black, although her superstructure remained grey.

As a troopship, Queen Elizabeth left Singapore on 11 February, and initially she carried Australian troops to operating theatres in Asia and Africa.[12] After 1942, the two Queens were relocated to the North Atlantic for the transportation of American troops to Europe.[12]

Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary were used as troop transports during the war. Their high speeds allowed them to outrun hazards, principally German U-boats, usually allowing them to travel without a convoy.[11] During her war service as a troopship Queen Elizabeth carried more than 750,000 troops, and she also sailed some 500,000 miles (800,000 km).[5] Her captains during this period were Townley, Ernest Fall, Cyril Gordon Illinsworth, Charles Ford, and James Bisset.

Post-war career

Following the end of World War II, her sister ship Queen Mary remained in her wartime role and grey appearance, except for her funnels, which were repainted in the company's colours. For another year she did military service, returning troops and G.I. brides to the United States. Queen Elizabeth, meanwhile, was refitted and furnished as an ocean liner[5] at the Firth of Clyde Drydock in Greenock by the John Brown Shipyard. Six years of war service had never permitted the formal sea trials to take place, and these were now finally undertaken. Under the command of Commodore Sir James Bisset the ship travelled to the Isle of Arran and her trials were carried out. Onboard was the ship's namesake Queen Elizabeth and her two daughters, the princesses Elizabeth and Margaret.[5] During the trials, her majesty Queen Elizabeth took the wheel for a brief time and the two young princesses recorded the two measured runs with stopwatches that they had been given for the occasion. Bisset was under strict instructions from Sir Percy Bates, who was also aboard the trials, that all that was required from the ship was two measured runs of no more than thirty knots and that she was not permitted to attempt to attain a higher speed record than Queen Mary. After her trials Queen Elizabeth finally entered Cunard White Star's two ship weekly service to New York.[13] Despite similar specifications to her older sister ship Queen Mary, Elizabeth never held the Blue Riband, as Cunard White Star chairman Sir Percy Bates requested that the two ships not try to compete against one another.

In 1955 during an annual overhaul at Southampton, England, Queen Elizabeth was fitted with underwater fin stabilizers to smooth the ride in rough seas. Two fins were fitted on each side of the hull. The fins were retractable into the hull to save fuel in smooth seas and for docking.[14]

In 1959, the ship made an appearance in the British satirical Eastman Color comedy film The Mouse That Roared starring Peter Sellers and Jean Seberg. While a troupe of invading men from a fictional European country cross the Atlantic to 'war' with the United States on a tow boat, they meet and pass the far larger Queen Elizabeth, and learn that New York City is closed due to an air raid drill. The men on the tow boat respond by loosing arrows at the two officers speaking from near the ocean liner's bridge.

The ship ran aground on a sandbank off Southampton on 14 April 1947, and was re-floated the following day.[5] On 29 July 1959, she was in a collision with the American cargo ship American Hunter in foggy conditions in New York Harbour and was holed above the waterline.[15]

Together with the Queen Mary, and in competition with SS United States, the Queen Elizabeth dominated the transatlantic passenger trade until their fortunes began to decline with the advent of the faster and more economical jet airliner in the late 1950s.[11] As passenger numbers declined, the Queens became uneconomic to operate in the face of rising fuel and labour costs. For a short time, the Queen Elizabeth (now under the command of Commodore Geoffrey Trippleton Marr) attempted a dual role in order to become more profitable; when not plying her usual transatlantic route, which she now alternated in her sailings with the French Line's SS France, the ship cruised between New York and Nassau.[5] For this new tropical purpose, the ship received a major refit in 1965, with a new lido deck added to her aft section, enhanced air conditioning, and an outdoor swimming pool. With these improvements, Cunard intended to keep the ship in operation until at least the middle 1970s.[16] However, this strategy did not prove successful due to her high fuel costs, deep draught (which prevented her from entering various island ports), and great width, preventing her from using the Panama Canal.

Cunard retired both ships by 1969 and replaced them with a single, smaller ship, the more economical Queen Elizabeth 2.

Final years

In 1968, Queen Elizabeth was sold to a group of American businessmen from a company called The Queen Corporation (which was 85% owned by Cunard and 15% by them). The new company intended to operate the ship as a hotel and tourist attraction in Port Everglades, Florida, similar to the use of Queen Mary in Long Beach, California.[5] Elizabeth, as she was now called, actually opened to tourists before Queen Mary (which opened in 1971) but it was not to last. The climate of southern Florida was much harder on Queen Elizabeth than the climate of southern California was on Queen Mary. Losing money and forced to close after being declared a fire hazard, the ship was sold at auction in 1970 to Hong Kong tycoon Tung Chao Yung.[5]

Tung, head of the Orient Overseas Line, intended to convert the vessel into a university for the World Campus Afloat program (later reformed and renamed as Semester at Sea). Following the tradition of the Orient Overseas Line, the ship was renamed Seawise University, as a play on Tung's initials.[5]

Near the completion of the £5 million conversion, the vessel caught fire on 9 January 1972.[5] There is some suspicion that the fires were set deliberately, as several blazes broke out simultaneously throughout the ship.[17] The fact that C.Y. Tung had acquired the vessel for $3.5 million, and had insured it for $8 million, led some to speculate that the inferno was part of a fraud to collect on the insurance claim. Others speculated that the fires were the result of a conflict between Tung, a Chinese Nationalist, and Communist-dominated ship construction unions.[18]

The ship was completely destroyed by the fire, and the water sprayed on her by fireboats caused the burnt wreck to capsize and sink in Hong Kong Victoria Harbour.[19] The vessel was finally declared a shipping hazard and dismantled for scrap between 1974 and 1975. Portions of the hull that were not salvaged were left at the bottom of the bay. The keel and boilers remained at the bottom of the harbour and the area was marked as "Foul" on local sea charts warning ships not to try to anchor there. It is estimated that around 40–50% of the wreck was still on the seabed. In the late 1990s, the final remains of the wreck were buried during land reclamation for the construction of Container Terminal 9.[20] Position of wreck: 22°19.717′N 114°06.733′E / 22.328617°N 114.112217°E.[21] Queen Elizabeth is surpassed only by Costa Concordia in 2012 as the largest passenger shipwreck.

After the fire, Tung had one of the liner's anchors and the metal letters "Q" and "E" from the name on the bow placed in front of the office building at Del Amo Fashion Center in Torrance, California, US, that was intended to be the headquarters of the Seawise University venture,[22] where they remain to this day.[23] Two of the ship's fire warning system brass plaques were recovered by a dredger and these are now on display at The Aberdeen Boat Club in Hong Kong within a display area about the ship. The charred remnants of her last ensign were cut from the flag pole and framed in 1972, and still adorn the wall of the officers' mess of marine police HQ in Hong Kong. Parker Pen Company produced a special edition of 5,000 pens made from material recovered from the wreck in a presentation box and these are highly collectable.[24]

Following the demise of Queen Elizabeth, the largest passenger ship in active service became SS France, which was longer but had less tonnage than the Cunard liner.

Fictional appearances

The charred wreck was featured in the 1974 James Bond film The Man with the Golden Gun, as a covert headquarters for MI6.[25][26] Q's labs are in the wreckage of this ship.

References

- ↑ Pride of the North Atlantic, A Maritime Trilogy, David F. Hutchings. Waterfront 2003

- ↑ "Big Liners Steel Frame Work Rises as Workers Speed Up" Popular Mechanics, September 1937, left-side pg 346. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ "Classic Liners and Cruise Ships - Queen Elizabeth". Cruiseserver.net. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ RMS Queen Elizabeth from Victory to Valhalla. pp. 10

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Cunard Queen Elizabeth 1940 - 1972". Cunard.com. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- 1 2 3 4 Maxtone-Graham, John. The Only Way to Cross. New York: Collier Books, 1972, p. 355

- ↑ "Pathe newsreel from 1938 reporting on new ship build".

- ↑ RMS Queen Elizabeth, The Beautiful Lady. Janette McCutcheon, The History Press Ltd (8 November 2001)

- ↑ The Liverpool Post, 23 August 1937

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 358-60

- 1 2 3 Floating Palaces. (1996) A&E. TV Documentary. Narrated by Fritz Weaver

- 1 2 "Rms. Queen Elizabeth". Ayrshire Scotland. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 396

- ↑ "Big Liner Sprouts Fins." Popular Science, June 1955, pp. 122-124.

- ↑ "Liner Queen Elizabeth in Collision". The Times (54526). London. 30 July 1959. col A, p. 6.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 409

- ↑ "Arson Suspected as Blaze Destroys Queen Elizabeth". News.google.com. 1972-01-10. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ "On This Day: The Queen Elizabeth Mysteriously Sinks in a Hong Kong Harbor". Findingdulcinea.com. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ "Queen Elizabeth". Chriscunard.com. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ "Sea queen to lie below CT9". Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ "Providing Sufficient Water Depth for Kwai Tsing Container Basin and its Approach Channel Environmental Impact Assessment Report — Appendix 9.3 UK Hydrographic Office Data" (PDF). Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ↑ http://www.cruisetalkshow.com/id181.html

- ↑ http://linerlogbook.blogspot.com/2010/12/queen-elizabeth-in-torrance.html

- ↑ "Modern Pens for Sale: The Parker 75 and 105 Limited Editions". Penhome.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- ↑ "RMS Queen Elizabeth". Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Hann, Michael (3 October 2012). "My favourite Bond film: The Man with the Golden Gun". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

Further reading

- Britton, Andrew (2013). RMS Queen Elizabeth. Classic Liners series. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. ISBN 9780752479514.

- Butler, D.A. (2002). Warrior Queens: The Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth in World War II (1st ed.). Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books.

- Galbraith, R (1988). Destiny's Daughter: The Tragedy of RMS Queen Elizabeth. Vermont: Trafalgar Square.

- Varisco, R (2013). RMS Queen Elizabeth: Cunard's Big Beautiful Ship of Life. Gold Coast: Blurb Books.

- Harvey, Clive, 2008, R.M.S Queen Elizabeth The Ultimate Ship, Carmania Press London, ISBN 978-0-95436668-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Queen Elizabeth (ship, 1940). |

- The Great Ocean Liners: Queen Elizabeth

- RMS Queen Elizabeth story and picture

- RMS Queen Elizabeth (I) on Chris' Cunard Page

- Pathe newsreel of Queen Elizabeth being built