Sir William Gordon-Cumming, 4th Baronet

Sir William Alexander Gordon Gordon-Cumming, 4th Baronet (20 July 1848 – 20 May 1930) was a Scottish landowner, soldier, adventurer and socialite. A notorious womaniser, he is best known for being the central figure in the royal baccarat scandal of 1891. After inheriting a baronetcy he joined the Army and saw service in South Africa, Egypt and the Sudan; he served with distinction and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Something of an adventurer, he also spent time hunting in the US and India.

A friend of Edward, Prince of Wales for over 20 years, in 1891 he attended a house party at Tranby Croft, Yorkshire, where he took part in a game of baccarat at the behest of the prince. During the course of two nights' play he was accused of cheating, which he denied vehemently. After news of the affair leaked out, he sued five members of the host family for slander; the Prince of Wales was called as a witness. The case was a public spectacle, widely reported in the UK and abroad, but the judgement went against Gordon-Cumming and he was ostracised from polite society.

A handsome, arrogant man, Gordon-Cumming was a womaniser, particularly with married women. After the court case he married an American heiress; the couple had five children, but it was an unhappy relationship. He was the grandfather of the writers Katie Fforde and Jane Gordon-Cumming.

Early life

William Gordon Gordon-Cumming was born on 20 July 1848 at Sanquhar House, near Forres, Morayshire.[1] His parents were Alexander Penrose Gordon-Cumming and his wife Anne Pitcairn née Campbell (died 1888). The big-game hunter Roualeyn George Gordon-Cumming was his uncle; and the travel writer Constance Gordon-Cumming was his aunt. He was educated at Eton and Wellington colleges.[2][3]

At the age of eighteen he inherited the baronetcy and became chief of the Clan Cumming; his line had been traced from the fourth century, through Charlemagne. His inheritance included three Morayshire estates: Altyre near Forres, Gordonstoun near Elgin and Dallas. Though the estates totalled 38,500 acres (156 km2), they yielded poor revenues;[2] the annual income from the estates in around 1890 has been described as either £60,000[4] or £80,000.[5]

Professional career

Although Gordon-Cumming suffered from asthma and was blind in one eye, he purchased an ensign's commission in the Scots Fusilier Guards (later the Scots Guards) in 1868 (dated from 25 December 1867).[2][6] He was promoted to regimental lieutenant and to the rank of captain in the army by purchase on 17 May 1871, the last year commissions were allowed to be purchased.[7] He volunteered for service in South Africa in the Anglo-Zulu War, where he served gallantly, and was the first man to enter Cetshwayo's kraal after the Battle of Ulundi (1879). That year he conveyed the condolences of the army to the Empress Eugénie on the death of her son, Napoléon, Prince Imperial.[2]

Gordon-Cumming was promoted to the regimental rank of captain and the army rank of lieutenant-colonel on 28 July 1880.[8] He went on to serve in Egypt, in the Anglo-Egyptian War (1882) and in the Sudan in the Mahdist War (1884–85), the last of which was with the Guards Camel Regiment in the Desert Column.[3][4] He was promoted to regimental major on 23 May 1888.[9]

He also found time for independent adventure, hunting in the Rocky Mountains in the U.S. and in India, where he would stalk tigers on foot;[2][4] in 1871 he published an account of his travels in India, Wild Men & Wild Beasts. Scenes in camp and jungle .[10]

Royal baccarat scandal

In September 1890 Gordon-Cumming was invited, along with Edward, Prince of Wales, to a house party at Tranby Croft in Yorkshire. There he was accused of cheating at baccarat by placing additional counters onto his stake after the hand had finished, but before the stake had been paid—a method of cheating known in casinos as la poussette.[11] Gordon-Cumming insisted they had been mistaken, and explained that he played the coup de trois system of betting,[lower-alpha 1] in which if he won a hand with a £5 stake, he would add his winnings to the stake, together with another £5, as the stake for the next hand.[12]

In order to avoid a scandal involving the prince, he gave way to pressure from the attendant royal courtiers to sign a statement undertaking never to play cards again in return for a pledge that no-one present would speak of the incident again.[13][14]

"In consideration of the promise made by the gentlemen whose names are subscribed to preserve my silence with reference to an accusation which has been made in regard to my conduct at baccarat on the nights of Monday and Tuesday the 8th and 9th at Tranby Croft, I will on my part solemnly undertake never to play cards again as long as I live."— (Signed) W. Gordon-Cumming[15]

Despite the pledge of silence, rumours of the incident began to circulate and were brought to Gordon-Cumming's attention. In an attempt to scotch the rumours, he demanded a retraction from five of the house party; when that was not forthcoming, with no withdrawal forthcoming, on 6 February 1891, Gordon-Cumming issued writs for slander against the five, claiming £5,000 against each of them.[16][lower-alpha 2]

The trial opened on 1 June 1891 and entry to the court was by ticket only. The Prince of Wales was present, and sat on a red leather chair on a raised platform between the judge and the witness box;[18] his appearance was the first time since 1411 that an heir to the throne had appeared involuntarily in court.[2][lower-alpha 3]

The trial closed the following week, after the judge's summing up "had been unacceptably biased", according to Tomes.[2] The jury deliberated for only 13 minutes before finding in favour of the defendants; their decision was greeted by prolonged hissing from some members of the galleries.[20] The day after judgement was passed, the leader in The Times stated that "He is ... condemned by the verdict of the jury to social extinction. His brilliant record is wiped out and he must, so to speak, begin life again. Such is the inexorable social rule ... He has committed a mortal offence. Society can know him no more."[21]

Gordon-Cumming's senior counsel, the Solicitor General Sir Edward Clarke, remained convinced in his client and, in his 1918 memoirs, wrote that "I believe the verdict was wrong, and that Sir William Gordon-Cumming was innocent".[22]

Aftermath

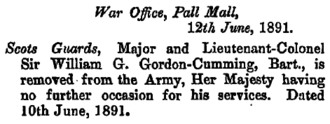

As a result of the scandal, Gordon-Cumming was dismissed from the army the day after the trial,[23] and he resigned his membership of his four London clubs, the Carlton, Guards', Marlborough and Turf.[2]

The same day he married his American fiancée, the heiress Florence Garner, who had stood by him throughout the trial despite Gordon-Cumming twice offering to break off their engagement because of the scandal.[24] The service took place at the Holy Trinity church in Chelsea with only a small congregation.[25][26] When the couple returned to Scotland a few days later the locals from near his estate had decorated the station and pulled the carriage through the streets by hand. According to the former Lord Chancellor, Michael Havers, the lawyer Edward Grayson and the historian Peter Shankland, "That the prince and society considered him a social outcast mattered not at all to his people".[27] The prince was determined Gordon-Cumming should remain ostracised and he "declined to meet anyone who henceforth acknowledged the Scottish baronet".[2]

Later life

Gordon-Cumming remained outside high society for the remainder of his life. He later told his daughter that "among a host of acquaintances I thought I had perhaps twenty friends. Not one of them ever spoke to me again".[28] Others of his friends only relented after the death of the prince, who was by that stage King Edward VII.[2][29]

Gordon-Cumming and his wife had three sons and two daughters between 1892 and 1904.[30] In 1905 Florence's fortune slumped and the couple were compelled to let or close up the houses on the Scottish estates and to move to Bridge House, Dawlish, Devon with a reduced household.[2] Gordon-Cumming managed to disguise his contempt for the middle class society to which he was now limited so that he could continue to indulge himself in golf, croquet, billiards, cricket, bridge and collecting post marks. He also enjoyed his own company, and that of his dogs and pet monkey. He hated Dawlish and considered his wife a "fat little frump", unapologetically engaging in chronic infidelity. Florence lost no opportunity to remind him who funded their life but eventually herself resorted to alcohol abuse;[2] the couple had effectively separated before she died in 1922.[3]

In 1916 Gordon-Cumming ensured that the Labour Party politician Ramsay MacDonald had his membership rescinded from the Moray Golf Club because of the latter's opposition to the First World War.[2]

Gordon-Cumming died on 20 May 1930 at his Altyre home at the age of 81. He was succeeded in his title by his eldest son, Major Alexander Penrose Gordon-Cumming, MC.[3]

Private life

Gordon-Cumming's biographer, Jason Tomes, thought that his subject possessed "audacity and wit [and] gloried in the sobriquet of the most arrogant man in London",[2] while Sporting Life described him as "possibly the most handsome man in London, and certainly the rudest".[31] Gordon-Cumming also owned a house in Belgravia, London; he was a friend of the Prince of Wales, and would lend the premises to the prince for assignations with the royal mistresses.[3][32]

Gordon-Cumming was a womaniser,[33] and stated that his aim was to "perforate" members of "the sex".[2] His preference was for uncomplicated relationships with married women, and he admitted that "all the married women try me";[34] his liaisons included Lillie Langtry, Sarah Bernhardt and Lady Randolph Churchill.[2][32] In 1890, three days before the events at Tranby Croft, the Prince of Wales returned early from travelling in Europe; he visited Harriet Street where he found his mistress, Daisy, Lady Brooke "in Gordon-Cumming's arms", which soured the relationship between the two men.[31]

After Gordon-Cumming's death in 1930, his house at Gordonstoun was obtained by Kurt Hahn, who turned it into the eponymous school. It has been attended by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and his three sons, Charles, Andrew and Edward.[35]

Two of Gordon-Cumming's granddaughters, Katie Fforde and Jane Gordon-Cumming, became writers.[36]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Also known as the masse en avant system.[12]

- ↑ £5,000 is approximately £460,000 in 2014.[17]

- ↑ In 1411 it was Prince Henry who was committed for contempt of court by Judge William Gascoigne.[19]

References

- ↑ "Gordon-Cumming, Sir William Gordon". Who Was Who. Oxford: A & C Black. 2007. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Tomes 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Sir William Gordon-Cumming". The Times. London. 21 May 1930. p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Havers, Grayson & Shankland 1988, p. 41.

- ↑ Hibbert 2007, p. 160.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 23336. p. 7008. 24 December 1867. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 23737. p. 2350. 16 May 1871. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 24871. p. 4312. 6 August 1880. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 25824. p. 3127. 5 June 1888. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ "Wild Men & Wild Beasts. Scenes in camp and jungle". British Library Catalogue. London: British Library. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ↑ Magnus-Allcroft 1975, p. 280.

- 1 2 Havers, Grayson & Shankland 1988, p. 27.

- ↑ Teignmouth Shore 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ Havers, Grayson & Shankland 1988, pp. 35–37.

- ↑ "The Baccarat Scandal: The Truth About Tranby Croft". The Manchester Gazette. Manchester. 19 February 1891. p. 8.

- ↑ "The Baccarat Scandal". The Times. London. 3 March 1891. p. 10.

- ↑ UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ "The Baccarat Case". Pall Mall Gazette. London. 1 June 1891. p. 4.

- ↑ Havers, Grayson & Shankland 1988, p. 69.

- ↑ McHugh 2008, p. 174.

- ↑ "Leading Article: The Baccarat Case". The Times. London. 10 June 1891. p. 9.

- ↑ Clarke 1918, p. 298.

- 1 2 The London Gazette: no. 26171. p. 3118. 12 June 1891.

- ↑ Havers, Grayson & Shankland 1988, p. 248.

- ↑ "Cumming Takes a Bride". The New York Times. New York. 11 June 1891.

- ↑ Havers, Grayson & Shankland 1988, pp. 248–49.

- ↑ Havers, Grayson & Shankland 1988, p. 251.

- ↑ Havers, Grayson & Shankland 1988, p. 263.

- ↑ Matthew 2004.

- ↑ Attwood 1988, pp. 116–17.

- 1 2 Attwood 1988, p. 88.

- 1 2 Ridley 2012, p. 281.

- ↑ Diamond 2004, p. 33.

- ↑ Ridley 2012, p. 285.

- ↑ Attwood 1988, p. 117.

- ↑ "Katie Fforde". AudioBooksOnline. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

Sources

- Attwood, Gertrude (1988). The Wilsons of Tranby Croft. London: Hutton Press. ISBN 978-0-907033-71-4.

- Clarke, Sir Edward (1918). The Story of my Life. London: Penguin Books.

- Diamond, Michael (2004). Victorian Sensation. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-84331-150-8.

- Havers, Michael; Grayson, Edward; Shankland, Peter (1988). The Royal Baccarat Scandal. London: Souvenir Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-285-62852-6.

- Hibbert, Christopher (2007). Edward VII: The Last Victorian King. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-8377-0.

- Magnus-Allcroft, Philip (1975). King Edward the Seventh. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-002658-0.

- Matthew, H.C.G. (2004). "Edward VII (1841–1910)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32975. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- McHugh, Michael (2008). "The Rise (and Fall?) of the Barrister Class". In Gleeson, Justin; Higgins, Ruth. Rediscovering Rhetoric: Law, Language, and the Practice of Persuasion. Annandale, NSW: Federation Press. ISBN 978-1-86287-705-4.

- Ridley, Jane (2012). Bertie: A Life of Edward VII. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-7614-3.

- Teignmouth Shore, W. (ed.) (2006) [1932]. The Baccarat Case. London: Butterworth & Co. ISBN 978-1-84664-787-1.

- Tomes, Jason (2010). "Cumming, Sir William Gordon Gordon-, fourth baronet (1848–1930)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/39392. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

| Baronetage of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alexander Penrose Gordon-Cumming |

Baronet (of Altyre) 1866–1930 |

Succeeded by Alexander Penrose Gordon-Cumming |