Sleeping Beauty (1959 film)

| Sleeping Beauty | |

|---|---|

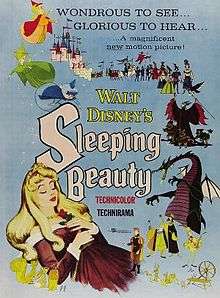

Original theatrical poster | |

| Directed by |

Supervising Director Clyde Geronimi Sequence Directors Les Clark Eric Larson Wolfgang Reitherman |

| Produced by | Walt Disney |

| Written by | Erdman Penner |

| Story by |

|

| Based on |

La Belle au bois dormant by Charles Perrault The Sleeping Beauty by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Little Briar Rose by The Brothers Grimm |

| Starring | |

| Narrated by | Marvin Miller |

| Music by |

George Bruns (score) Jack Lawrence (score) Tom Adair (songs) |

| Edited by |

Robert M. Brewer, Jr. Donald Halliday |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Distribution |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 75 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6 million[1] |

| Box office | $51.6 million[2] |

Sleeping Beauty is an American animated musical fantasy film produced by Walt Disney based on The Sleeping Beauty by Charles Perrault and Little Briar Rose by The Brothers Grimm. The 16th film in the Disney animated feature film, it was released to theaters on January 29, 1959, by Buena Vista Distribution. This was the last Disney adaptation of a fairy tale for some years because of its initial mixed critical reception and underperformance at the box office; the studio did not return to the genre until 30 years later, after Walt Disney died in 1966, with the release of The Little Mermaid (1989).

It features the voices of Mary Costa, Eleanor Audley, Verna Felton, Barbara Luddy, Barbara Jo Allen, Bill Shirley, Taylor Holmes, and Bill Thompson.

The film was directed by Les Clark, Eric Larson, and Wolfgang Reitherman, under the supervision of Clyde Geronimi, with additional story work by Joe Rinaldi, Winston Hibler, Bill Peet, Ted Sears, Ralph Wright, and Milt Banta. The film's musical score and songs, featuring the work of the Graunke Symphony Orchestra under the direction of George Bruns, are arrangements or adaptations of numbers from the 1890 Sleeping Beauty ballet by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Along with Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Igor Stravinsky's music composition was also popular in the film.

Sleeping Beauty was the first animated film to be photographed in the Super Technirama 70 widescreen process, as well as the second full-length animated feature film to be filmed in anamorphic widescreen, following Disney's own Lady and the Tramp four years earlier. The film was presented in Super Technirama 70 and 6-channel stereophonic sound in first-run engagements.

Plot

After many childless years, King Stefan and Queen Leah happily welcome the birth of their daughter, Princess Aurora. They proclaim a holiday for their subjects to pay homage to the princess. At the gathering for her christening, she is betrothed to Prince Phillip, the young son of King Hubert, Stefan's friend, so that their kingdoms will always be united.

Among the guests are three good fairies: Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather, who have come to bless the child with gifts. Flora and Fauna give their blessings (beauty and song, respectively). Just before Merryweather can speak, the evil fairy Maleficent appears. Angered upon not being invited to the christening, Maleficent curses the princess, proclaiming that before the sun sets on her sixteenth birthday, she will prick her finger on the spindle of an enchanted spinning wheel and die. After Maleficent leaves, Merryweather uses her blessing to weaken the curse so that Aurora instead will fall into a deep sleep from which she can only be awakened by true love's first kiss. Stefan, still fearful for his daughter's life, orders all spinning wheels in the kingdom to be burned. The fairies do not believe that will be enough to keep Aurora safe, and so they take Aurora away to a woodcutter's cottage in the forest, living as mortals, until the day of her sixteenth birthday.

Years later, Aurora, renamed Briar Rose, has grown up into a beautiful young maiden. On the day of her sixteenth birthday, the three fairies ask Rose to gather berries in the forest so they can prepare a surprise party for her. Meanwhile, Maleficent, in frustration, has her raven Diablo search for Aurora after her bumbling demon soldiers fail to find her. In the forest, Rose's beautiful singing voice attracts the attention of Phillip, now a handsome young man. They instantly fall in love, unaware of being betrothed many years ago. Rose asks Phillip to come to the cottage in the glen that evening to meet her, without telling each other's names.

Having difficulty sewing together a ball gown and preparing a birthday cake for Rose, the fairies resort to magic. Fighting over the dress' color, the magic with puffs exiting the chimney of the cottage attracts the attention of Diablo. When Rose arrives, the fairies tell her the truth about her royal heritage, and that she cannot see her newfound love stranger. Heartbroken, Rose leaves the room. Overhearing this, Diablo departs to inform Maleficent. At the same time, Phillip tells his father of a peasant girl whom he met and wishes to marry in spite of his prearranged marriage to Aurora. Hubert fails to convince him otherwise, leaving him in equal disappointment.

The fairies take Aurora back to the castle that evening. Maleficent lures Aurora away from the fairies and tricks the princess into pricking her finger on a spinning wheel's spindle, completing the curse, and sending Aurora into a deep sleep. The fairies put Aurora on a bed in the highest tower and cast a gentle spell on everyone in the castle, putting them all to fall sleep until the curse is broken. From Hubert's conversation with Stefan, Flora realizes that Phillip is the stranger whom Aurora has fallen in love with. However, he has been ambushed and kidnapped by Maleficent and her minions at the cottage. They take him to Maleficent's castle on Forbidden Mountain and imprison him in the dungeon. Maleficent shows Phillip that the peasant girl and the now peacefully sleeping Aurora are one and the same. She plans to keep him locked away until he is an old man on the verge of death, then releases him to meet his love, who will not have aged a single day.

After Maleficent returns to her tower, the fairies arrive at the castle, where they narrowly avoid being spotted. Luckily, they find and release Phillip, arming him with the Sword of Truth and the Shield of Virtue. The fairies and Phillip then proceed to escape on his horse Samson. In the process, Merryweather also turns Diablo to stone, but the cries alert Maleficent to the prince's escape. As Phillip and the fairies make their way toward King Stefan's castle, Maleficent tries to stop him with a series of lightning bolts, and even conjuring a forest of thorns to surround the castle, but all her attempts fail. She then teleports herself to the castle gate and transforms into a gigantic dragon then battles the prince. The battle moves onto a cliff, where a blast of Maleficent's flame causes Phillip to lose his shield. Just as Maleficent is about to destroy him, the three fairies fly to Phillip's aid. Blessing it with all their magic, Phillip throws the sword directly into Maleficent's heart. Mortally wounded, Maleficent collapses over the cliff.

Now that Maleficent been destroyed, the forest of thorns disappears. In the highest tower, he finds his true love, still asleep. He kisses Aurora and she awakens, finally breaking the curse and waking up everyone in the palace. The royal couple descends to the ballroom, where Aurora is happily reunited with her overjoyed parents, despite Hubert's confusion. As Aurora dances with Phillip, Flora, and Merryweather resume their argument over the color of Aurora's dress, changing it to pink and blue and back again. Aurora and Phillip live happily ever after.

Cast

| Role | Actor | Voice | Singer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Princess Aurora/Briar Rose, the Sleeping Beauty | Helene Stanley | Mary Costa | |

| Prince Phillip | Ed Kemmer | Bill Shirley | |

| Maleficent | Eleanor Audley | ||

| Fairies | Frances Bavier Madge Blake Spring Byington |

Verna Felton Barbara Jo Allen Barbara Luddy | |

| King Stefan | Taylor Holmes | ||

| King Hubert | Bill Thompson | ||

| Queen Leah | Rosa Crosby | ||

| Diablo | Dallas McKennon | ||

| Vernon the Prince Owl | |||

| Samson | |||

| Maleficent's goons | Candy Candido Pinto Colvig Bob Amsberry | ||

| Narrator | Marvin Miller | ||

Directing animators

- Marc Davis - (Princess Aurora, Maleficent)

- Milt Kahl - (Prince Phillip)

- Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston - (The Three Good Fairies: Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather)

- John Lounsbery - (King Hubert, King Stefan)

Eric Larson did not animate any of the characters for the film; instead, he directed the entire "Forest" sequence which stretches from Briar Rose (a.k.a. Aurora) wandering through the forest with her animal friends all the way to Princess Aurora renamed Briar Rose running back home, promising Phillip they will meet again later in the evening. This was the only time he directed a sequence or a film during his tenure at Walt Disney Feature Animation.

Production

Story development

Following the critical and commercial success of Cinderella, writing for Sleeping Beauty began in early 1951. Partial story elements originated from discarded ideas for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs including Maleficent's capture of Prince Philip and his dramatic escape from her fortress and Cinderella where a fantasy sequence featured the leading protagonists dancing on a cloud which was developed, but eventually dropped from the film.[3] By the middle of 1953, director Wilfred Jackson had recorded the dialogue, assembled a story reel, and was to commence for preliminary animation work where Princess Aurora and Prince Phillip were to meet in the forest and dance, though Walt Disney decided to throw out the sequence delaying the film from its initial 1955 release date.[4] For a number of months, Jackson, Ted Sears, and two story writers underwent a rewrite of the story, which received a lukewarm response from Disney. During the story rewriting process, the story writers felt the original fairy tale's second act felt bizarre and with the wake-up kiss serving as a climactic moment, they decided to concentrate on the first half finding strength in the romance. However, they felt little romance was developed between the strange prince and the princess that the storyboard artists worked out an elaborate sequence in which the king organized a treasure hunt. The idea was eventually dropped when it became too drawn out and drifted from the central storyline. Instead, it was written that Prince Phillip and Princess Aurora would meet in the forest by random chance while Princess Aurora renamed Briar Rose was conversing with the forest animals. Additionally, because the original Perrault tale had the curse last one hundred years, the writers decided to shorten it a few hours with the time spent for Prince Phillip to battle the goons, overcome several obstacles, and fight off against Maleficent transformed into a dragon.[5]

The name given to the princess by her royal birth parents is "Aurora" (Latin for "dawn"), as it was in the original Tchaikovsky ballet. This name occurred in Charles Perrault's version as well, not as the princess's name, but as her daughter's.[6] In hiding, she is called Briar Rose, the name of the princess in the Brothers Grimm's version variant.[7] The prince was given the princely name most familiar to Americans in the 1950s: Prince Phillip. Named after Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, the character has the distinction of being the first Disney prince to have a name as the two princes in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (The Prince) and Cinderella (Prince Charming) are never named.

In December 1953, Jackson suffered a heart attack, as a result of which directing animator Eric Larson of Disney's Nine Old Men took over as director. By April 1954, Sleeping Beauty was scheduled for a February 1957 release.[4] With Larson as the director, Disney instructed Larson, whose unit would animate the forest sequence,[8] that the picture was to be a "moving illustration, the ultimate in animation" and added that he did not care how long it would take. Because of the delays, the release date was again pushed back from Christmas 1957 to Christmas 1958. Fellow Nine Old Men Milt Kahl would blame Walt for the numerous release delays because "he wouldn’t have story meetings. He wouldn't get the damn thing moving."[9] Relatively late in production, Disney removed Larson as the supervising director and replaced him with Clyde Geronimi.[4][10] Directing animator Wolfgang Reitherman would join Geronimi as sequence director over the climactic dragon battle sequence commenting that "We took the approach that we were going to kill that damned prince!".[11] Les Clark, another member of the Nine Old Men, would serve as the sequence director of the elaborate opening scene where crowds of the citizens in the kingdom arrive at the palace for the presentation of Princess Aurora.[12]

Art direction

Kay Neilsen–whose sketches were the basis for Night on Bald Mountain in Fantasia–was the first to produce styling sketches for the film in 1952.[13] The artistic style originated when John Hench observed the famed unicorn tapestries at the Cloisters located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. When Hench returned to the Disney studios, he brought reproductions of the tapestries and showed them to Walt Disney, who replied, "Yeah, we could use that style for Sleeping Beauty."[14]

Eyvind Earle joined Walt Disney Productions in 1951 first employed as an assistant background painter for Peter Pan before being promoted as a full-fledged background painter in the Goofy cartoon, "For Whom the Bulls Toil" and the color stylist of the Academy Award-winning short, Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom.[4][15] For Sleeping Beauty, Earle said he "felt totally free to put my own style" into the paintings he based on Hench's drawings stating "Where his trees might have curved, I straightened them out…. I took a Hench and took the same subject, and the composition he had, and just turned in into my style."[16] Furthermore, Earle found inspiration in Italian Renaissance utilizing works from Albrecht Dürer, Pieter Bruegel, Nicolaas van Eyck, Sandro Botticelli, as well as Persian art and Japanese prints.[17] When Geronimi became the supervising director, Earle and Geronimi entered furious creative divisions. Geronimi commented that he felt Earle's paintings "lacked the mood in a lot of things. All that beautiful detail in the trees, the bark, and all that, that's all well and good, but who the hell's going to look at that? The backgrounds became more important than the animation. He'd made them more like Christmas cards."[8] Earle left the Disney studios in March 1958, before Sleeping Beauty was completed, to take a job at the John Sutherland studio. As a result, Geronimi had Earle's background paintings softened and diluted from their distinctive medieval texture.[18]

Animation

Live-action reference footage

Before the animation process began, a live-action reference version was filmed with live actors in costume serving as models for the animators in which Walt Disney insisted on because he wanted the characters to appear "as real as possible, near flesh-and-blood." However, Milt Kahl objected to this method, calling it "a crutch, a stifling of the creative effort. Anyone worth his salt in this business ought to know how people move."[19] Helene Stanley was the live action reference for Princess Aurora.[20] The only known surviving footage of Stanley as Aurora's live-action reference is a clip from the television program Disneyland, which consists of the artists sketching her dancing with the woodland animals. Stanley previously provided live-action references for Cinderella[21][22] and later for Anita from 101 Dalmatians,[21] and portrayed Polly Crockett for the TV series Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier.

The role of Prince Phillip was modeled by Ed Kemmer,[22] who had played Commander Buzz Corry on television's Space Patrol[23][24] five years before Sleeping Beauty was released. For the final battle sequence, Kemmer was photographed on a wooden buck. The live-action model for Maleficent was Eleanor Audley, who also voiced the villain.[25] Dancer Jane Fowler also was a live-action reference for Maleficent.[22][26][27] Among the actresses who performed in reference footage for this film were Spring Byington and Frances Bavier.

Character animation

Because of the artistic depth of Earle's backgrounds, it was decided for the characters to be stylized so they could appropriately match the backgrounds.[28] While the layout artists and animators were impressed with Earles's paintings, they eventually grew depressed at working with a style that many of them regarded as too cold, too flat, and too modernist for a fairy tale. Nevertheless, Walt insisted on the visual design claiming that the inspirational art he commissioned in the past had homogenized the animators.[29] Frank Thomas would complain to Ken Peterson, head of the animation department, of Earles's "very rigid design" because of the inhibiting effect on the animators that was less problematic than working with Mary Blair's designs, in which Peterson would respond that the design style was Walt's decision, and that, like it or not, they had to use it.[16] Because of this, Thomas developed a red blotch on his face and had to visit the doctor each week to have it attended to. Production designer Ken Anderson also complained: "I had to fight myself to make myself draw that way." Another character animator on Aurora claimed their unit was so cautious about the drawings that the clean-up animators produced one drawing a day, which translated into one second of screen time per month.[30]

Meanwhile, Tom Oreb was tasked as character stylist that would not only inhabit the style of the backgrounds, but also fit with the contemporary UPA style. Likewise with Earle's background styling, the animators complained that the character designs were too rigid to animate.[31] For Maleficent, Marc Davis drew from Czechoslovakian religious paintings and used "the red and black drapery in the back that looked like flames that I thought would be great to use. I took the idea of the collar partly from a bat, and the horns looked like a devil." However, in an act of artistic compromise, Earle, with final approval on the character designs, requested the change to lavender as red would come off too strong, which Davis agreed to.[32] In addition, Davis served as directing animator over the title character with the character's figure and features based on those of Audrey Hepburn as well as her voice actress, Mary Costa.[33]

Veteran animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston were assigned as directing animators over the three good fairies: Flora, Fauna and Merryweather. Walt Disney urged for the fairies to be more homogeneous, which Thomas and Johnston objected to, with Thomas stating they "thought 'that's not going to be any fun'. So we started figuring the other way and worked on how we could develop them into special personalities."[34] John Lounsbery would animate the "Skumps" sequence between Kings Hubert and Stefan.[28] Chuck Jones, known for his work as an animation director with Warner Bros. Cartoons, was employed on the film for four months during its early conceptual stages when Warner Bros. Cartoons was closed when it was anticipated that 3-D film would replace animation as a box office draw. Following the failure of 3-D, and the reversal of Warner's decision, Jones returned to the other studio. His work on Sleeping Beauty, which he spent four months on, remained uncredited. Ironically, during his early years at Warner Bros., Jones was a heavy user of Disney-style animation.

Casting

In 1952, Mary Costa was invited to a dinner party where she sang "When I Fall in Love" at the then-named Los Angeles Conservatory of Music. Following the performance, she was approached by Walter Schumann who told her, "I don't want to shock you, but I've been looking (for Aurora) for three years, and I want to set up an audition. Would you do it?" Costa accepted the offer, and at her audition in the recording booth with George Bruns, she was asked to sing and do a bird call, which she did initially in her Southern accent until she was advised to do an English accent. The next day, she was informed by Walt Disney that she landed the role.[35][36] Eleanor Audley initially turned down the choice role of Maleficent as she was battling tuberculosis at the time, but reconsidered.[37]

Music

In April 1952, Billboard reported that Jack Lawrence and Sammy Fain had signed to compose the score.[38] Walter Schumann was originally slated to be the film composer, but left the project because of creative differences with Walt Disney. George Bruns was recommended to replace Schumannn by animator Ward Kimball. Because of a musicians' strike in 1957, the musical score was recorded in Berlin, Germany.[39]

Track list:

- "Main Title"/"Once Upon a Dream"/"Prologue"

- "Hail to the Princess Aurora"

- "The Gifts of Happiness and Song"/"Maleficent Appears"/"True Love Conquers All"

- "The Burning of the Spinning Wheels"/"The Fairies' Plan"

- "Maleficent's Frustration"

- "A Cottage in the Woods"

- "Do You Hear That?"/"I Wonder"

- "An Unusual Prince"/"Once Upon a Dream (Reprise)"

- "Magical House Cleaning"/"Blue or Pink"

- "A Secret Revealed"

- "Wine (Drinking Song)"/"The Royal Argument"

- "Prince Phillip Arrives"/"How to Tell Stefan"

- "Aurora's Return"/"Maleficent's Evil Spell"

- "Poor Aurora"/"Sleeping Beauty"

- "Forbidden Mountain"

- "A Fairy Tale Come True"

- "Battle with the Forces of Evil"

- "Awakening"

- "Finale (Once Upon a Dream (third-prise))"

The Classic Disney: 60 Years of Musical Magic album includes "Once Upon a Dream" on the green disc, and "I Wonder" on the purple disc. Additionally, Disney's Greatest Hits includes "Once Upon a Dream" on the blue disc. The 1973 LP compilation 50 Happy Years of Disney Favorites (Disneyland, STER-3513) includes "Once Upon a Dream" as the seventh track on Side IV, as well as a track titled "Blue Bird – I Wonder" labeled as being from this film with authorship by Hibler, Sears, and Bruns (same set, Side II, track 4).

No Secrets performed a cover version of "Once Upon a Dream" on the album Disneymania 2, which appears as a music video on the 2003 DVD. More recently, Emily Osment sang a remake of "Once Upon a Dream", released on the Disney Channel on September 12, 2008, and included on the Platinum Edition DVD and Blu-ray Disc.

In the 2012 album Disney – Koe no Oujisama, which features various Japanese voice actors covering Disney songs, "Once Upon a Dream" was covered by Toshiyuki Morikawa.

In anticipation of the 2014 film Maleficent, a cover version sung by Lana Del Rey was released by Disney on January 26. The song is considerably darker and more dramatic than the 1959 version, given the new film's focus on the villain Maleficent. The song was debuted in a trailer for the film shown as a commercial break during the 2014 Grammy Awards, and was released for free on Google Play for a limited time.[40][41]

Release

Original theatrical run

Disney's distribution arm, Buena Vista Distribution, originally released Sleeping Beauty to theaters in both standard 35mm prints and large-format 70mm prints. The Super Technirama 70 prints were equipped with six-track stereophonic sound; some CinemaScope-compatible 35mm Technirama prints were released in four-track stereo, and others had monaural soundtracks. On the initial run, Sleeping Beauty was paired with the short musical/documentary film Grand Canyon which won an Academy Award.[42]

During its original release in January 1959, Sleeping Beauty grossed $6.2 million at the box office,[43] but amounted approximately $5.3 million in theater rentals (the distributor's share of the box office gross).[44] Sleeping Beauty's production costs, which totaled $6 million,[1] made it the most expensive Disney film up to that point, and over twice as expensive as each of the preceding three Disney animated features: Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, and Lady and the Tramp.[45] The high production costs of Sleeping Beauty, coupled with the underperformance of much of the rest of Disney's 1959–1960 release slate, resulted in the company posting its first annual loss in a decade for fiscal year 1960,[1] and there were massive lay-offs throughout the animation department.[46]

Re-releases

Like Alice in Wonderland (1951), which was not initially successful either, Sleeping Beauty was never re-released theatrically in Walt Disney's lifetime. However, it had many re-releases in theaters over the decades. The film was re-released theatrically in 1970,[47] where it was released on standard 35mm film. The release garnered $3.8 million.[43] It was re-released in 1979 in 70mm 6 channel stereo, as well as in 35 mm stereo and mono,[48] 1986,[49] and 1995.[50] It was going to be re released in 1993 (as was advertised on the 1992 VHS of Beauty and the Beast) but it was canceled. Sleeping Beauty's successful reissues have made it the second most successful film released in 1959, second to Ben-Hur,[51] with a lifetime gross of $51.6 million.[2] When adjusted for ticket price inflation, the domestic total gross comes out to $623.56 million, placing it in the top 40 of films.[52]

From July 9 to August 13, 2012, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences organized "The Last 70MM Film Festival" at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater, where the Academy, its members, and the Hollywood industry acknowledged the importance, beauty, and majesty of the 70mm film format and how its image and quality is superior to that of digital film. The Academy selected the following films, which were shot on 70mm, to be screened to make a statement about it, as well as to gain a new appreciation for familiar films in a way it hadn't before: It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, Sleeping Beauty, Grand Prix, The Sound of Music, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Spartacus, along with other short subject films on the 70mm format.[53] A screening of the final remaining 70mm print of this film will be included in the 70mm & Widescreen Film Festival at the Somerville Theatre, September 18, 2016.[54]

Critical reaction

Upon its initial release, Sleeping Beauty received mixed to positive reviews from film critics. Bosley Crowther, writing in his review for The New York Times, complimented that "the colors are rich, the sounds are luscious and magic sparkles spurt charmingly from wands" and compared the film favorably to Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs writing that "the princess looks so much like Snow White they could be a couple of Miss Rheingolds separated by three or four years. And she has the same magical rapport with the little creatures of the woods. The witch is the same slant-eyed Circe who worked her evil on Snow White. And the three good fairies could be maiden sisters of the misogynistic seven dwarfs."[55] Variety praised the singing voices of Mary Costa and Bill Shirley and noted that "some of the best parts of the picture are those dealing with the three good fairies, spoken and sung by Verna Felton, Barbara Jo Allen and Barbara Luddy."[56]

Nevertheless, the film has sustained a strong following and is today hailed as one of the best animated films ever made, thanks to its stylized designs by painter Eyvind Earle who also was the art director for the film, its lush music score, the character of Maleficent (whose popularity led her to be the flagship villain for the Disney Villains franchise) and its large-format 70mm widescreen and stereophonic sound presentation. Rotten Tomatoes gave the film a "Certified Fresh" 92% from 38 reviews with an average rating of 8.2/10. Its consensus states that "This Disney dreamscape contains moments of grandeur, with its lush colors, magical air, one of the most menacing villains in the Disney canon."[57] Carrie R. Wheadon of Common Sense Media gave the film five out of five stars, writing, "Disney classic is delightful but sometimes scary".[58]

Awards and honors

- Best Scoring of a Musical Picture (George Bruns) (Lost against Porgy and Bess)

- Best Soundtrack Album, Original Cast – Motion Picture or Television (Lost against Porgy and Bess)

- Best Musical Entertainment Featuring Youth – TV or Motion Picture (Lost against Nutcracker Fantasy)

Other honors

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

- Maleficent – Nominated Villain[62]

- 2006: AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals – Nominated[63]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Animation Film[64]

Home media

Sleeping Beauty was released on VHS, Betamax and Laserdisc in 1986 in the Classics collection, becoming the first Disney Classics video to be digitally processed in Hi-Fi stereo. During its 1986 VHS release, it sold over a million copies.[65] The film underwent a digital restoration in 1997, and that version was released to both VHS and Laserdisc again as part of the Masterpiece Collection. The 1997 VHS edition also came with a special commemorative booklet included, with brief facts on the making of the movie. In 2003, the restored Sleeping Beauty was released to DVD in a 2-disc "Special Edition" which included both a widescreen version (formatted at 2.35:1) and a pan and scan version as well. Its DVD supplements included the making-of featurette from the 1997 VHS, Grand Canyon, the Life of Tchaikovsky segment of The Peter Tchaikovsky Story from the Walt Disney anthology television series,[66] a virtual gallery of concept art, layout and background designs, three trailers, and audio commentary from Mary Costa, Eyvind Earle, and Ollie Johnston.[67]

A Platinum Edition release of Sleeping Beauty, as a 2-disc DVD and Blu-ray, was released on October 7, 2008 in the US, making Sleeping Beauty the first entry in the Platinum Edition line to be released in high definition video. This release is based upon the 2007 restoration of Sleeping Beauty from the original Technicolor negatives (interpositives several generations removed from the original negative were used for other home video releases). The new restoration features the film in its full negative aspect ratio of 2.55:1, wider than both the prints shown at the film's original limited Technirama engagements in 2.20:1 and the CinemaScope-compatible reduction prints for general release at 2.35:1. The Blu-ray set features BD-Live, an online feature, and the extras include a virtual castle and multi-player games.[68] The Blu-ray release also includes disc 1 of the DVD version of the film in addition to the two Blu-rays. The DVD includes a music video with a remake of the Disney Classic "Once Upon A Dream" sung by Emily Osment; and featuring Daniel Romer as Prince Charming. The DVD was released on October 27, 2008 in the UK. The Blu-ray release is the first ever released on the Blu-ray format of any Disney feature produced by Walt Disney himself. The film was released on a Diamond Edition Blu-ray, DVD, and Digital HD on October 7, 2014, after six years since its first time on Blu-ray.

Legacy

Video games

- Aurora is one of the seven Princesses of Heart in the popular Square Enix game Kingdom Hearts (although her appearances are brief), and Maleficent is a villain in all three Kingdom Hearts games, and as a brief ally at the third game's climax. The good fairies appear in Kingdom Hearts II, giving Sora new clothes. Diablo appears in Kingdom Hearts II to resurrect his defeated mistress. The PSP game Kingdom Hearts Birth by Sleep, features a world based on the movie, Enchanted Dominion, and characters who appear are Princess Aurora/Briar Rose, Maleficent, Maleficent's goons, the three faires and Prince Phillip, the latter serving as temporary party member for Aqua during her battle against Maleficent and her henchmen.

- She is also a playable character in the game Disney Princess.

Board game

Walt Disney's Sleeping Beauty Game (1958) is a Parker Brothers children's board game for two to four players based upon Sleeping Beauty. The object of the game is to be the first player holding three different picture cards to reach the castle and the space marked "The End".[69]

The Disney film retains the basics of Charles Perrault's 17th-century fairy tale about a princess cursed to sleep one hundred years, but adds three elderly fairies who protect the princess, a prince armed with a magic sword and shield, and other details. The Disney twists on the tale are incorporated into the game, and Disney's "stunning graphics"[69] illustrate the game board. In addition to the board game, the film generated books, toys, and other juvenile merchandise.

The equipment consists of a center-seamed game board, four tokens in various colors, four spinners, four magic wands, and a deck of picture cards.

The first player moves the number of spaces along the track according to a dial spin. If the player lands on a pink star, his turn ends. If he lands on a yellow star, he draws a card and follows its instruction. If he draws a picture card, he retains it face down at his place. If a player spins a six, he is given the choice of moving six spaces or taking a magic wand. He may play the wand at any time during the game and in doing so draws two cards, following their instructions. A player must hold three different picture cards before entering the Path of Happiness. If he does not hold three picture cards, he continues around the Deep Sleep circle until he acquires the required three picture cards. Should a player land on a purple Maleficent space, that player returns one of his picture cards to the deck.

Theme parks

Sleeping Beauty was made while Walt Disney was building Disneyland (hence the six-year production time). To help promote the film, Imagineers named the park's icon "Sleeping Beauty Castle" (it was originally to be Snow White's). An indoor walk-through exhibit was added to the empty castle interior in 1957, where guests could walk through the castle, up and over the castle entrance, viewing "Story Moment" dioramas of scenes from the film, which were improved with animated figurines in 1977. It closed shortly after the September 11, 2001 attacks, supposedly because the dark, unmonitored corridors were a risk. After being closed for seven years, the exhibit space underwent extensive refurbishment to restore the original 1957 displays, and reopened to guests on November 27, 2008. Accommodations were also made on the ground floor with a "virtual" version for disabled guests unable to navigate stairs. Hong Kong Disneyland opened in 2005, also with a Sleeping Beauty Castle, nearly replicating Disneyland's original design.

Le Château de la Belle au Bois Dormant at Disneyland Paris is a variant of Sleeping Beauty Castle. The version found at Disneyland Paris is much more reminiscent of the film's artistic direction. The Château features an animatronic dragon, imagineered to look like Maleficent's dragon form, is found in the lower level dungeon – La Tanière du Dragon.[70] The building also contains La Galerie de la Belle au Bois Dormant, a gallery of displays which illustrate the story of Sleeping Beauty in tapestries, stained glass windows and figures.[71]

Princess Aurora (and, to a lesser extent, Prince Phillip, the three good fairies, and Maleficent) makes regular appearances in the parks and parades.

Maleficent is featured as one of the villains in the nighttime show Fantasmic! at Disneyland and Disney's Hollywood Studios.

Other appearances

Maleficent's goons appear in the Maroon Cartoon studio lot in the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit. The Bluebirds from the film also appear as "tweeting birds" that fly around Roger Rabbit's or Eddie Valiant's heads in two scenes, after a refrigerator fell on top of Roger's head and while Eddie Valiant is in Toontown, the birds are seen again flying around his head until he shoos them away.

Princess Aurora, Prince Phillip, Flora, Fauna and Merryweather were featured as guests in Disney's House of Mouse and Maleficent was one of the villains in Mickey's House of Villains. The first all-new story featuring the characters from the movie (sans Maleficent) appeared in Disney Princess Enchanted Tales: Follow Your Dreams, the first volume of collection of the Disney Princesses. It was released on September 4, 2007. Mary Costa, the original voice of Princess Aurora, was not fond of this story and felt that it did not work.[72]

In the American fantasy drama series Once Upon a Time, a live-action version of Maleficent appeared in the second episode and the Season 1 finale, as she is an adversary of the Evil Queen, and is also sinister. She appears more prominently in the show's fourth season. Her role is played by True Blood actress Kristin Bauer. In Season 2, Season 3, and Season 4 live-action incarnations of Princess Aurora, Prince Phillip, and King Stefan are portrayed by Sarah Bolger, Julian Morris, and Sebastian Roché respectively.

Flora, Fauna and Merryweather appear in Disney Channel/Disney Junior's series Sofia the First as the teaching faculty of Royal Prep, the school for the various kingdom's princes and princesses. Princess Aurora also makes a guest appearance in the episode, "Holiday in Enchancia".

Stage adaptation

A scaled-down one act stage musical version of the film with the title Disney's Sleeping Beauty KIDS is often performed by schools and children's theaters.[73] With book and additional lyrics by Marcy Heisler and Bryan Louiselle, the show is composed of twelve musical numbers, including the movie songs.[74]

Live-action remake

In Walt Disney Pictures' live action film Maleficent, released on May 2014, Angelina Jolie plays the role of Maleficent and Elle Fanning plays Princess Aurora. The movie was directed by Robert Stromberg in his directorial debut, produced by Don Hahn and Joe Roth, and written by Paul Dini and Linda Woolverton.[75]

See also

- Medieval fantasy

- List of Disney animated films based on fairy tales

- List of American films of 1959

- Sleeping Beauty Castle

References

- 1 2 3 Thomas 1976, pp. 294–5.

- 1 2 "Sleeping Beauty". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ↑ Robb, Brian (December 9, 2014). A Brief History of Walt Disney. Running Press. ISBN 978-0762454754. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Barrier 1999, p. 554.

- ↑ Koeing 2001, p. 104.

- ↑ Anne Heiner, Heidi (1999). "Annotations for Sleeping Beauty". SurLaLune Fairy Tales.

- ↑ Ashliman, D.L. "Little Brier-Rose". University of Pittsburgh.

- 1 2 Clyde Geronimi (March 16, 2015). "Gerry Geronimi - An Interview by Michael Barrier and Milton Gray" (Interview). Interview with Michael Barrier and Milton Gray. MichaelBarrier.com. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ↑ Gabler 2006, p. 558–9.

- ↑ Gabler 2006, p. 560.

- ↑ Folkart, Burt (May 24, 1985). "Wolfgang Reitherman, 75 : Disney Animator Dies in Car Crash". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ↑ Deja, Andreas (January 3, 2013). "The Art of Sleeping Beauty". Deja View. Blogger. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ↑ Barrier 1999, p. 555.

- ↑ Thomas 1997, p. 104–5.

- ↑ Oliver, Myrna (July 25, 2000). "Eyvind Earle; Artist and Disney Painter". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- 1 2 Barrier 1999, p. 557.

- ↑ Thomas 1997, p. 105.

- ↑ Barrier 1999, p. 558.

- ↑ Maltin 1987, p. 74.

- ↑ Disney Family Album: Marc Davis. YouTube. Retrieved 2013-08-04.

- 1 2 "Cinderella Character History". Disney Archives. Archived from the original on 2012-06-24.

- 1 2 3 Leonard Maltin. The Disney Films: 3rd Edition. p. 156. ISBN 0-7868-8137-2.

- ↑ Sleeping Beauty at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Animation (2012-11-13). "Sleeping Beauty". Tv Facts. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ↑ Andreas Deja (2011-08-31). "Deja View: Miss Audley". Andreasdeja.blogspot.ru. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ↑ Thomas S. Hischak. Disney Voice Actors: A Biographical Dictionary. p. 13. ISBN 9780786462711.

- ↑ Andreas Deja (2013-03-29). "Deja View: Moments with Marc". Andreasdeja.blogspot.ru. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- 1 2 Picture Perfect: The Making of Sleeping Beauty (Documentary film). Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment. 2009.

- ↑ Gabler 2006, p. 558.

- ↑ Gabler 2006, p. 558–60.

- ↑ Reif, Alex (October 6, 2014). "From the Vault: The History of "Sleeping Beauty"". The Laughing Place. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Marc Davis: Style & Compromise on Sleeping Beauty". The Walt Disney Family Museum.

- ↑ Das, Lina (11 December 2008). "Disney's Dames: As Sleeping Beauty turns 50, we reveal the stories behind Walt's heroines...". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ Korkis, Jim (June 20, 2015). "In His Own Words: Frank Thomas on the "Sleeping Beauty" Fairies". Cartoon Research. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ↑ Noyer, Jérémie (October 7, 2008). "Once Upon A Dream: Mary Costa as Sleeping Beauty's Princess Aurora" (Interview). Interview with Mary Costa. Animated Views. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ↑ Clark, John (October 26, 2008). "Mary Costa, voice of Sleeping Beauty". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ↑ Sleeping Beauty Platinum Edition (Audio commentary). John Lasseter, Andreas Deja, John Canemaker. Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2008.

- ↑ "Lawrence, Fain to Score "Beauty"". Billboard. Google Books. April 19, 1952. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ↑ Giez, Didier (September 30, 2011). Walt's People: Talking Disney with the Artists who Knew Him, Volume 11. Xlibris. pp. 306–11. ISBN 978-1465368409. Retrieved October 27, 2015.

- ↑ Graser, Marc (26 January 2014). "Disney's Maleficent Takes Advantage of Grammys With Lana Del Rey Song". Variety. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ↑ Mendelson, Scott (26 January 2014). "Lana Del Rey Covers 'Once Upon A Dream' For Angelina Jolie's 'Maleficent'". Forbes. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ↑ "Disney Readies Film About Grand Canyon". Deseret News. January 6, 1959. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- 1 2 Thomas, Bob (September 16, 1979). "'Beauty' napped at the box office". Associated Press. St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ↑ Schickel, Richard (1968). The Disney Version: The Life, Times, Art and Commerce of Walt Disney. Chicago: Simon & Schuster. p. 299. ISBN 1-5666-3158-0.

- ↑ Barrier 1999, pp. 554–59.

- ↑ Norman, Floyd (August 18, 2008). "Toon Tuesday: Here's to the real survivors". Retrieved February 13, 2010.

- ↑ "Cinema Scene". Ludington Daily News. July 10, 1979. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ Gaul, Lou (November 20, 1979). "Unappetizing Thanksgiving movie menu". Beaver County Times. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ Thomas, Bob (April 11, 1986). "A Renaissance: Animated films are enjoying a surprise". Evening Independent. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ↑ Disney's Sleeping Beauty (1995 Re-Release Trailer) Youtube, Retrieved July 28, 2016

- ↑ "Movies: Top 5 Box Office Hits, 1939 to 1988". Ldsfilm.com. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ↑ "All Time Box Office Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation". Boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ↑ "The Last 70MM Film Festival". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ↑ "70 mm Presentations". Somerville Theatre. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (February 18, 1959). "Screen: 'Sleeping Beauty'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Review: 'Sleeping Beauty'". Variety. December 31, 1958. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Sleeping Beauty Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ↑ Carrie R. Wheadon. "Sleeping Beauty – Movie Review". Commonsensemedia.org. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ↑ "The 32nd Academy Awards 1960". The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Grammy Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ↑ "First Annual Youth in Film Awards 1978–1979". Young Artist Awards. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ "AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-19.

- ↑ Yarrow, Andrew (February 22, 1988). "Video Cassettes Pushing Books Off Shelves". The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ↑ Germain, David (September 13, 2003). "Disney's grand 1959 animated 'Sleeping Beauty' released on DVD". Associated Press. Eugene Register-Guard. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ↑ King, Susan (September 13, 2003). "Disney dusts off 'Sleeping Beauty'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Sleeping Beauty Blu-ray Disc release". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- 1 2 Chertoff, Nina, and Susan Kahn. Celebrating Board Games. Sterling Publishing Co., Inc., 2006

- ↑ "La Tanière du Dragon, Disneyland Paris". DLP Guide. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ↑ "La Galerie de la Belle au Bois Dormant, Disneyland Paris". DLP Guide. Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- ↑ Mary Costa Interview - Page 2. Retrieved November 13, 2012.

- ↑ "Disney's Sleeping Beauty KIDS". Mtishows.com. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ↑ "Music Theatre International: Licensing Musical Theater Theatrical Performance Rights and Materials to Schools, Community and Professional Theatres since 1952". Mtishows.com. Retrieved 2014-04-13.

- ↑ Maleficent at the Internet Movie Database

Bibliography

- Barrier, Michael (April 8, 1999). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802079-0.

- Gabler, Neal (2006). Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-679-75747-4.

- Koenig, David (January 28, 2001). Mouse Under Glass: Secrets of Disney Animation & Theme Parks. Bonaventure Press. ISBN 978-0964060517.

- Maltin, Leonard (1987). Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons. Plume. ISBN 978-0452259935.

- Thomas, Bob (1976). Walt Disney: An American Original (1994 ed.). New York: Hyperion Press. ISBN 0-7868-6027-8.

- Thomas, Bob (March 7, 1997). Disney's Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse To Hercules. Disney Editions. ISBN 978-0786862412.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sleeping Beauty (1959 film) |

- Official website

- Sleeping Beauty at AllMovie

- Sleeping Beauty at The Big Cartoon DataBase

- Sleeping Beauty at the Internet Movie Database

- Sleeping Beauty at the TCM Movie Database

- Sleeping Beauty at Rotten Tomatoes