Small-cell carcinoma

| Small-cell carcinoma | |

|---|---|

| |

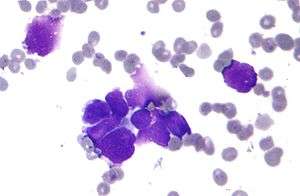

| Micrograph of a small-cell carcinoma of the lung showing cells with nuclear moulding, minimal amount of cytoplasm and stippled chromatin. FNA specimen. Field stain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-O | M8041/3 |

| MedlinePlus | 000122 |

| eMedicine | med/1336 |

| MeSH | D018288 |

Small-cell carcinoma (also known as "small-cell lung cancer", or "oat-cell carcinoma") is a type of highly malignant cancer that most commonly arises within the lung,[1] although it can occasionally arise in other body sites, such as the cervix,[2] prostate,[3] and gastrointestinal tract. Compared to non-small cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma has a shorter doubling time, higher growth fraction, and earlier development of metastases.

Clinical presentation

Small-cell carcinoma of the lung usually presents in the central airways and infiltrates the submucosa leading to narrowing of bronchial airways. Common symptoms include cough, dyspnea, weight loss, and debility. Over 70% of patients with small-cell carcinoma present with metastatic disease; common sites include liver, adrenals, bone, and brain.

Cytopathology

Small-cell carcinoma is an undifferentiated neoplasm composed of primitive-appearing cells.

As the name implies, the cells in small-cell carcinomas are smaller than normal cells, and barely have room for any cytoplasm. Some researchers identify this as a failure in the mechanism that controls the size of the cells.[4]

Paraneoplastic syndromes

Due to its high grade neuroendocrine nature, small-cell carcinomas can produce ectopic hormones, including adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and anti-diuretic hormone (ADH). Ectopic production of large amounts of ADH leads to syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone hypersecretion (SIADH).

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is a well-known paraneoplastic condition linked to small-cell carcinoma.[5]

Lung

_by_core_needle_biopsy.jpg)

When associated with the lung, it is sometimes called "oat cell carcinoma" due to the flat cell shape and scanty cytoplasm.

It is thought to originate from neuroendocrine cells (APUD cells) in the bronchus called Feyrter cells (named for Friedrich Feyrter).[6] Hence, they express a variety of neuroendocrine markers, and may lead to ectopic production of hormones like ADH and ACTH that may result in paraneoplastic syndromes and Cushing's syndrome.[7] Approximately half of all individuals diagnosed with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) will eventually be found to have a small-cell carcinoma of the lung.[5]

Small-cell carcinoma is most often more rapidly and widely metastatic than non-small cell lung carcinoma[8] (and hence staged differently). There is usually early involvement of the hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes. [7]

Combined small-cell lung carcinoma (c-SCLC)

Small-cell lung carcinoma can occur in combination with a wide variety of other histological variants of lung cancer,[9] including extremely complex malignant tissue admixtures.[10] [11] When it is found with one or more differentiated forms of lung cancer, such as squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, the malignant tumor is then diagnosed and classified as a combined small cell lung carcinoma (c-SCLC).[9] C-SCLC is the only currently recognized subtype of SCLC.[9]

Although combined small-cell lung carcinoma is currently staged and treated similarly to "pure" small-cell carcinoma of the lung, recent research suggests surgery might improve outcomes in very early stages of this tumor type.

Smoking is a significant etiological factor.

Symptoms and signs are as for other lung cancers. In addition, because of their neuroendocrine cell origin, small-cell carcinomas will often secrete substances that result in paraneoplastic syndromes such as Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome.

Extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma

Very rarely, the primary site for small-cell carcinoma is outside of the lungs and pleural space, it is referred to as extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma (EPSCC). Outside of the respiratory tract, small-cell carcinoma can appear in the cervix, prostate, liver, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, or bladder.[12] It is estimated to account for 1,000 new cases a year in the U.S. Histologically similar to small-cell lung cancer, therapies for small-cell lung cancer are usually used to treat EPSCC.[13] First line treatment is usually with cisplatin and etoposide. In Japan, the first line treatment is shifting to irinotecan and cisplatin.

When the primary site is in the skin, it is referred to as Merkel cell carcinoma.

Extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma localized in the lymph nodes

This is an extremely rare type of small cell, and there has been little information in the scientific community. It appears to occur in only one or more lymph nodes, and nowhere else in the body. Treatment is similar to small cell lung cancer, but survival rates are much higher than other small-cell carcinomas.[14]

Small-cell carcinoma of the prostate

In the prostate, small-cell carcinoma (SCCP) is a rare form of cancer (approx 1% of PC).[15] Due to the fact that there is little variation in prostate specific antigen levels, this form of cancer is normally diagnosed at an advanced stage, after metastasis.

It can metastasize to the brain.[16]

Treatment

Small-cell lung carcinoma has long been divided into two clinicopathological stages, including limited stage (LS) and extensive stage (ES). The stage is generally determined by the presence or absence of metastases, whether or not the tumor appears limited to the thorax, and whether or not the entire tumor burden within the chest can feasibly be encompassed within a single radiotherapy portal.[17] In general, if the tumor is confined to one lung and the lymph nodes close to that lung, the cancer is said to be LS. If the cancer has spread beyond that, it is said to be ES.

LS-SCLC

In cases of LS-SCLC, combination chemotherapy (often including cyclophosphamide, cisplatinum, doxorubicin, etoposide, vincristine and/or paclitaxel) is administered together with concurrent chest radiotherapy (RT).

Chest RT has been shown to improve survival in LS-SCLC.

Exceptionally high objective initial response rates (RR) of between 60% and 90% are seen in LS-SCLC using chemotherapy alone, with between 45% and 75% of individuals showing a "complete response" (CR), which is defined as the disappearance of all radiological and clinical signs of tumor. However, relapse rate remains high, and median survival is only 18 to 24 months.

Because SCLC usually metastasizes widely very early on in the natural history of the tumor, and because nearly all cases respond dramatically to chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, there has been little role for surgery in this disease since the 1970s.[18] However, recent work suggests that in cases of small, asymptomatic, node-negative SCLC's ("very limited stage"), surgical excision may improve survival when used prior to chemotherapy ("adjuvant chemotherapy").[19]

ES-SCLC

In ES-SCLC, combination chemotherapy is the standard of care, with radiotherapy added only to palliate symptoms such as dyspnea, pain from liver or bone metastases, or for treatment of brain metastases, which, in small-cell lung carcinoma, typically have a rapid, if temporary, response to whole brain radiotherapy.

Combination chemotherapy consists of a wide variety of agents, including cisplatin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and carboplatin. Response rates are high even in extensive disease, with between 15% and 30% of subjects having a complete response to combination chemotherapy, and the vast majority having at least some objective response. Responses in ES-SCLC are often of short duration, however.

If complete response to chemotherapy occurs in a subject with SCLC, then prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) is often used in an attempt to prevent the emergence of brain metastases. Although this treatment is often effective, it can cause hair loss and fatigue. Prospective randomized trials with almost two years follow-up have not shown neurocognitive ill-effects. Meta-analyses of randomized trials confirm that PCI provides significant survival benefits.

Prognosis

All in all, small-cell carcinoma is very responsive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and in particular, regimens based on platinum-containing agents. However, most people with the disease relapse, and median survival remains low.

In limited-stage disease, median survival with treatment is 14–20 months, and about 20% of patients with limited-stage small-cell lung carcinoma live 5 years or longer. Because of its predisposition for early metastasis, the prognosis of SCLC is poor, with only 10% to 15% of patients surviving 3 years.[21]

The prognosis is far more grim in extensive-stage small-cell lung carcinoma; with treatment, median survival is 8–13 months; only 1–5% of patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung carcinoma treated with chemotherapy live 5 years or longer.

Epidemiology

15% of lung cancers in the US are of this type.[22] Small cell lung cancer occurs almost exclusively in smokers; most commonly in heavy smokers and rarely in non-smokers.[23][24]

Genetics in small-cell carcinoma of the lungs (SCLCs)

TP53 is mutated in 70 to 90% of SCLCs. RB1 and the retinoblastoma pathway are inactivated in most SCLCs. PTEN is mutated in 2 to 10%. MYC amplifications and amplification of MYC family members are found in 30% of SCLCs. Loss of heterozygocity on chromosome arm 3p is found in more than 80% of SCLCs, including the loss of FHIT.[25] One hundred translocations have so far been reported in SCLCs (see the "Mitelman Database" [26] and the Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology,[27]).

See also

- Lung cancer

- Prostate cancer

- Brown–Séquard syndrome

- Cervical cancer

- Combined small-cell lung carcinoma

References

- ↑ "small-cell carcinoma" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Nasu K, Hirakawa T, Okamoto M, et al. (2011). "Advanced small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy with irinotecan and cisplatin followed by radical surgery". Rare Tumors. 3 (1): e6. doi:10.4081/rt.2011.e6. PMC 3070456

. PMID 21464879.

. PMID 21464879. - ↑ Capizzello A, Peponi E, Simou N, et al. (2011). "Pure small cellliterature review". Case Rep Oncol. 4 (1): 88–95. doi:10.1159/000324717. PMC 3072185

. PMID 21475596.

. PMID 21475596. - ↑ Leslie M (November 2011). "Mysteries of the cell. How does a cell know its size?". Science. 334 (6059): 1047–8. doi:10.1126/science.334.6059.1047. PMID 22116854.

- 1 2 Titulaer MJ, Verschuuren JJ (2008). "Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: tumor versus nontumor forms". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1132: 129–34. doi:10.1196/annals.1405.030. PMID 18567862.

- ↑ Champaneria MC, Modlin IM, Kidd M, Eick GN (2006). "Friedrich Feyrter: a precise intellect in a diffuse system". Neuroendocrinology. 83 (5-6): 394–404. doi:10.1159/000096050. PMID 17028417.

- 1 2 Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson. "Ch. 13, box on morphology of small-cell lung carcinoma". Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4160-2973-7.

- ↑ Cotran, Ramzi S.; Kumar, Vinay; Fausto, Nelson; Nelso Fausto; Robbins, Stanley L.; Abbas, Abul K. (2005). Robbins and Cotran pathologic basis of disease. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. p. 759. ISBN 0-7216-0187-1.

- 1 2 3 Travis, William D; Brambilla, Elisabeth; Muller-Hermelink, H Konrad; et al., eds. (2004). Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart (PDF). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press. ISBN 92-832-2418-3. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ↑ Pelosi G, Sonzogni A, Galetta D, et al. (April 2011). "Combined small-cell carcinoma of the lung with quadripartite differentiation of epithelial, neuroendocrine, skeletal muscle, and myofibroblastic type". Virchows Arch. 458 (4): 497–503. doi:10.1007/s00428-010-1011-8. PMID 21210145.

- ↑ Gotoh M, Yamamoto Y, Huang CL, Yokomise H (November 2004). "A combined small cell carcinoma of the lung containing three components: small cell, spindle cell and squamous cell carcinoma". Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 26 (5): 1047–9. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.08.002. PMID 15519208.

- ↑ Ismaili N (November 2011). "A rare bladder cancer – small cell carcinoma: review and update". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 6 (75). doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-75. PMC 3253713

. PMID 22078012.

. PMID 22078012. - ↑ Extrapulmonary Small Cell Carcinoma at eMedicine

- ↑

- ↑ Nutting C, Horwich A, Fisher C, Parsons C, Dearnaley DP (June 1997). "Small-cell carcinoma of the prostate". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 90 (6): 340–1. PMC 1296316

. PMID 9227387.

. PMID 9227387. - ↑ Erasmus CE, Verhagen WI, Wauters CA, van Lindert EJ (November 2002). "Brain metastasis from prostate small-cell carcinoma: not to be neglected". Can J Neurol Sci. 29 (4): 375–7. PMID 12463494.

- ↑ Argiris A, Murren JR (2001). "Staging and clinical prognostic factors for small-cell lung cancer". Cancer J. 7 (5): 437–47. PMID 11693903.

- ↑ Mountain CF (September 1978). "Clinical biology of small cell carcinoma: relationship to surgical therapy". Semin. Oncol. 5 (3): 272–9. PMID 211638.

- ↑ Shepherd FA (February 2010). "Surgery for limited stage small cell lung cancer: time to fish or cut bait". J Thorac Oncol. 5 (2): 147–9. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c8cbf5. PMID 20101141.

- ↑ Smokers defined as current or former smoker of more than 1 year of duration. See image page in Commons for percentages in numbers. Reference:

- Table 2 in: Kenfield SA, Wei EK, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA (2008). "Comparison of aspects of smoking among the four histological types of lung cancer.". Tob Control. 17 (3): 198–204. doi:10.1136/tc.2007.022582. PMC 3044470

. PMID 18390646.

. PMID 18390646.

- Table 2 in: Kenfield SA, Wei EK, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA (2008). "Comparison of aspects of smoking among the four histological types of lung cancer.". Tob Control. 17 (3): 198–204. doi:10.1136/tc.2007.022582. PMC 3044470

- ↑ [Washington, C. and Leaver, D. 2010. Principles and practice of radiation therapy. P 673. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier.]

- ↑ World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.1. ISBN 9283204298.

- ↑ Ettinger, DS; Aisner, J (1 October 2006). "Changing face of small-cell lung cancer: real and artifact.". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 24 (28): 4526–7. doi:10.1200/jco.2006.07.3841. PMID 17008688.

- ↑ Muscat, JE; Wynder, EL (6 January 1995). "Lung cancer pathology in smokers, ex-smokers and never smokers.". Cancer Letters. 88 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1016/0304-3835(94)03608-l. PMID 7850764.

- ↑ http://atlasgeneticsoncology.org/Tumors/TranslocLungSmallCellCarcID6651.html

- ↑ "Mitelman Database of Chromosome Aberrations and Gene Fusions in Cancer".

- ↑ "Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology". atlasgeneticsoncology.org.

Washington, C. and Leaver, D. 2010. Principles and practice of radiation therapy. P 673. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier.

Additional images

_by_core_needle_biopsy.jpg) Histopathologic image of small-cell carcinoma of the lung. CT-guided core needle biopsy.

Histopathologic image of small-cell carcinoma of the lung. CT-guided core needle biopsy.

External links

- Neuroimmunology - by Abid R Karim, Birmingham UK, at University of Birmingham Medical School

- Image at Tulane University

- -986382333 at GPnotebook