Southern strategy

In American politics, southern strategy refers to methods the Republican Party used to gain political support in the South by appealing to the racism against African Americans harbored by many southern white voters.[1][2][3]

As the African American Civil Rights Movement and dismantling of Jim Crow laws in the 1950s and 1960s visibly deepened pre-existing racial tensions in much of the Southern United States, Republican politicians such as presidential candidate Richard Nixon and Senator Barry Goldwater developed strategies that successfully contributed to the political realignment of many white, conservative voters in the South to the Republican Party that had traditionally supported the Democratic Party.[4]

In academia, "southern strategy" refers primarily to "top down" narratives of the political realignment of the South, which suggest that Republican leaders consciously appealed to many white southerners' racial resentments in order to gain their support.[5] This top-down narrative of the southern strategy is generally believed to be the primary force that transformed southern politics following the civil rights era.[6][7] This view has been questioned by historians such as Matthew Lassiter, Kevin M. Kruse and Joseph Crespino, who have presented an alternative, "bottom up" narrative, which Lassiter has called the "suburban strategy". This narrative recognizes the centrality of racial backlash to the political realignment of the South,[8] but suggests that this backlash took the form of a defense of de facto segregation in the suburbs, rather than overt resistance to racial integration, and that the story of this backlash is a national, rather than a strictly southern one.[9][10][11][12]

The perception that the Republican Party had served as the "vehicle of white supremacy in the South," particularly during the Goldwater campaign and the presidential elections of 1968 and 1972, made it difficult for the Republican Party to win the support of black voters in the South in later years.[4] In 2005, Republican National Committee chairman Ken Mehlman formally apologized to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a national civil rights organization, for exploiting racial polarization to win elections and ignoring the black vote.[13][14]

Introduction

Although the phrase "Southern strategy" is often attributed to Nixon's political strategist Kevin Phillips, he did not originate it[15] but popularized it.[16] In an interview included in a 1970 New York Times article, Phillips stated his analysis based on studies of ethnic voting:

- From now on, the Republicans are never going to get more than 10 to 20 percent of the Negro vote and they don't need any more than that...but Republicans would be shortsighted if they weakened enforcement of the Voting Rights Act. The more Negroes who register as Democrats in the South, the sooner the Negrophobe whites will quit the Democrats and become Republicans. That's where the votes are. Without that prodding from the blacks, the whites will backslide into their old comfortable arrangement with the local Democrats.[1]

While Phillips sought to increase Republican power by polarizing ethnic voting in general, and not just to win the white South, the South was by far the biggest prize yielded by his approach. Its success began at the presidential level. Gradually southern voters began to elect Republicans to Congress, and finally to statewide and local offices, particularly as some legacy segregationist Democrats retired or switched to the GOP. In addition, the Republican Party worked for years to develop grassroots political organizations across the South, supporting candidates for local school boards and city and county offices, as examples. But, following the Watergate scandal, in the 1976 election, southern voters came out in support for the "favorite son" candidate, Southern Democrat Jimmy Carter.

From 1948 to 1984 the Southern states, for decades a stronghold for the Democrats, became key swing states, providing the popular vote margins in the 1960, 1968 and 1976 elections. During this era, several Republican candidates expressed support for states' rights, a reversal of the position held by southern states prior to the Civil War. Some political analysts said this term was used in the 20th century as a "code word" to represent opposition to federal enforcement of civil rights for blacks and to federal intervention on their behalf; many individual southerners had opposed passage of the Voting Rights Act.[3]

Background

19th century Reconstruction to Solid South

During the Reconstruction era, 1863–1877, the Republican Party built up its base across the South, and for a while had control in each state except Virginia. From a national perspective, however, the Republican Party always gave priority to its much better established northern state operations. The northern party distrusted the scalawags, found the avaricious carpetbaggers distasteful, and lacked respect for the black component of their Republican Party in the South. Richard Abbott says that national Republicans always "stressed building their Northern base rather than extending their party into the South, and whenever the Northern and Southern needs conflicted the latter always lost."[17] In 1868, the GOP spent only five percent of its war chest in the South. Grant was reelected, and the New York Tribune advised it was now time for Southern Republicans to "root, hog, or die!" (that is, to take care of themselves).[18]

In a series of compromises, most famously in 1877, the Republican Party withdrew United States Army forces that had propped up its last three state governors and in return gained the White House for Rutherford B. Hayes.[19] All the southern states were now under the control of Democrats, who decade by decade increased their control of virtually all aspects of politics in the ex-Confederate states. There were occasional pockets of Republican control, usually in remote mountain districts.[20]

After 1890 the white Democrats used a variety of tactics to reduce voting by African Americans and poor whites.[21] In the 1880s they began to pass legislation making election processes more complicated and in some cases requiring payment of poll taxes, which created a barrier for poor people of both races.

From 1890 to 1908, the white Democratic legislatures in every Southern state enacted new constitutions or amendments with provisions to disenfranchise most blacks[22] and tens of thousands of poor whites. Provisions required payment of poll taxes, and complicated residency, literacy tests, and other requirements, which were subjectively applied against blacks. As blacks lost their vote, the Republican Party lost its ability to effectively compete in the South.[23] There was a dramatic drop in voter turnout as these measures took effect, a decline in African-American participation that was enforced for decades in all southern states.[24]

Blacks did have a voice in the Republican Party, especially in the choice of presidential candidates at the national convention. Boris Heersink and Jeffery A. Jenkins argue that in 1880–1928, GOP leaders at the presidential level adopted a “Southern strategy” by "investing heavily in maintaining a minor party organization in the South, as a way to create a reliable voting base at conventions." As a consequence, federal patronage did go to southern blacks, as long as there was a Republican in the White House. The issue exploded in 1912, when President William Howard Taft used control of the southern delegations to defeat former president Theodore Roosevelt at the Republican national convention,[25][26]

Because blacks were closed out of elected offices, the South's congressional delegations and state governments were dominated by white Democrats until the 1980s or later. Effectively, Southern white Democrats controlled all the votes of the expanded population by which Congressional apportionment was figured. Many of their representatives achieved powerful positions of seniority in Congress, giving them control of chairmanships of significant Congressional committees. Although the Fourteenth Amendment has a provision to reduce the Congressional representation of states that denied votes to their adult male citizens, this provision was never enforced. Because African Americans could not be voters, they were also prevented from being jurors and serving in local offices. Services and institutions for them in the segregated South were chronically underfunded by state and local governments, from which they were excluded.[27]

During this period, Republicans held only a few House seats from the South. Between 1880 and 1904, Republican presidential candidates in the South received between 35 and 40 percent of that section's vote (except in 1892, when the 16 percent for the Populists knocked Republicans down to 25 percent). From 1904 to 1948, after disenfranchisement, Republicans received more than 30 percent of the section's votes only in the 1920 (35.2 percent, carrying Tennessee) and 1928 elections (47.7 percent, carrying five states).

During this period, Republican administrations appointed blacks to political positions. Republicans regularly supported anti-lynching bills, but these were filibustered by Southern Democrats in the Senate. In the 1928 election, the Republican candidate Herbert Hoover rode the issues of prohibition and anti-Catholicism[28] to carry five former Confederate states, with 62 of the 126 electoral votes of the section. After his victory, Hoover attempted to build up the Republican Party of the South, transferring his limited patronage away from blacks and toward the same kind of white Protestant businessmen who made up the core of the Northern Republican Party. With the onset of the Great Depression, which severely affected the South, Hoover soon became extremely unpopular. The gains of the Republican Party in the South were lost. In the 1932 election, Hoover received only 18.1 percent of the Southern vote for re-election.

World War II and population changes

In the 1948 election, after Harry Truman signed an Executive Order to desegregate the Army, a group of Southern Democrats known as Dixiecrats split from the Democratic Party in reaction to the inclusion of a civil rights plank in the party's platform. This followed a floor fight led by Minneapolis mayor and (soon-to-be senator) Hubert Humphrey. The disaffected Democrats formed the States' Rights Democratic, or Dixiecrat Party, and nominated Governor Strom Thurmond of South Carolina for president. Thurmond carried four Deep South states in the general election: South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The main plank of the States' Rights Democratic Party was maintaining segregation and Jim Crow in the South. The Dixiecrats, failing to deny the Democrats the presidency in 1948, soon dissolved, but the split lingered. In 1964, Thurmond was one of the first conservative southern Democrats to switch to the Republican Party.[29][30]

In addition to the splits in the Democratic Party, the population movements associated with World War II had a significant effect in changing the demographics of the South. More than 5 million African Americans migrated from the South to the North and West in the second Great Migration, lasting from 1940 to 1970. Starting before WWII, many had moved to California for jobs in the defense industry, as well as to major industrial cities of the Midwest.[31]

With control of powerful committees, during and after the war, Southern Democrats gained new federal military installations in the South and other federal investments. Changes in industry, and growth in universities and the military establishment in turn attracted Northern transplants to the South, and bolstered the base of the Republican Party. In the post-war Presidential campaigns, Republicans did best in those fastest-growing states of the South that had the most Northern transplants. In the 1952, 1956 and 1960 elections, Virginia, Tennessee and Florida went Republican, while Louisiana went Republican in 1956, and Texas twice voted for Dwight D. Eisenhower and once for John F. Kennedy. In 1956, Eisenhower received 48.9 percent of the Southern vote, becoming only the second Republican in history (after Ulysses S. Grant) to get a plurality of Southern votes.[32]

The white conservative voters of the states of the Deep South remained loyal to the Democratic Party, which had not officially repudiated segregation. Because of declines in population or smaller rates of growth compared to other states, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas and North Carolina lost congressional seats from the 1950s to the 1970s, while South Carolina, Louisiana and Georgia remained static. Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected president in 1952, with strong support from the emerging middle class suburban element in the South. He appointed a number of Southern Republican supporters as federal judges in the South. They in turn ordered the desegregation of Southern schools in the 1950s and 1960s. They included Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals judges John R. Brown, Elbert P. Tuttle, and John Minor Wisdom, As well as district judges Frank Johnson and J. Skelly Wright.[33] However, five of his 24 appointees supported segregation.[34]

Roots of the Southern strategy (1963–1972)

The "Year of Birmingham" in 1963 highlighted racial issues in Alabama. Through the spring, there were marches and demonstrations to end legal segregation. The Movement's achievements in settlement with the local business class were overshadowed by bombings and murders by the Ku Klux Klan, most notoriously in the deaths of four girls in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing.[35]

After the Democrat George Wallace was elected as Governor of Alabama, he emphasized the connection between states' rights and segregation, both in speeches and by creating crises to provoke Federal intervention. He opposed integration at the University of Alabama, and collaborated with the Ku Klux Klan in 1963 in disrupting court-ordered integration of public schools in Birmingham.[35]

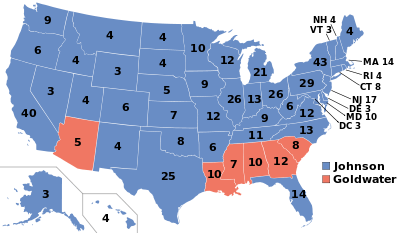

Many of the states' rights Democrats were attracted to the 1964 presidential campaign of conservative Republican Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona. Goldwater was notably more conservative than previous Republican nominees, such as Dwight D. Eisenhower. Goldwater's principal opponent in the primary election, Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York, was widely seen as representing the more moderate, pro-Civil Rights Act, Northern wing of the party (see Rockefeller Republican, Goldwater Republican).[36]

In the 1964 presidential campaign, Goldwater ran a conservative campaign that broadly opposed strong action by the federal government. Although he had supported all previous federal civil rights legislation, Goldwater decided to oppose the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[37] He believed that this act was an intrusion of the federal government into the affairs of states and, second, that the Act interfered with the rights of private persons to do business, or not, with whomever they chose, even if the choice is based on racial discrimination.

Goldwater's position appealed to white Southern Democrats, and Goldwater was the first Republican presidential candidate since Reconstruction to win the electoral votes of the Deep South states (Louisiana, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina). Outside the South, Goldwater's negative vote on the Civil Rights Act proved devastating to his campaign. The only other state he won was his home one of Arizona, and he suffered a landslide defeat. A Lyndon B. Johnson ad called "Confessions of a Republican," which ran in the North, associated Goldwater with the Ku Klux Klan. At the same time, Johnson’s campaign in the Deep South publicized Goldwater’s support for pre-1964 civil rights legislation. In the end, Johnson swept the election.[38]

At the time, Goldwater was at odds in his position with most of the prominent members of the Republican Party, dominated by so-called Eastern Establishment and Midwestern Progressives. A higher percentage of the Republican Party supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964[37] than did the Democratic Party, as they had on all previous Civil Rights legislation. The Southern Democrats mostly opposed their Northern Party mates — and their presidents (Kennedy and Johnson) — on civil rights issues. At the same time, passage of the Civil Rights Act caused many black voters to join the Democratic Party, which moved the party and its nominees in a progressive direction.[39]

Lyndon Johnson was concerned that his endorsement of Civil Rights legislation would endanger his party in the South. In the 1968 election, Richard Nixon saw the cracks in the Solid South as an opportunity to tap into a group of voters who had historically been beyond the reach of the Republican Party. George Wallace had exhibited a strong candidacy in that election, where he garnered 46 electoral votes and nearly 10 million popular votes, attracting mostly southern Democrats away from Hubert Humphrey.[40]

The notion of Black Power advocated by SNCC leaders captured some of the frustrations of African Americans at the slow process of change in gaining civil rights and social justice. African Americans pushed for faster change, raising racial tensions.[41] Journalists reporting about the demonstrations against the Vietnam War often featured young people engaging in violence or burning draft cards and American flags.[42] Conservatives were also dismayed about the many young adults engaged in the drug culture and "free love" (sexual promiscuity), in what was called the "hippie" counter-culture. These actions scandalized many Americans and created a concern about law and order.

Nixon's advisers recognized that they could not appeal directly to voters on issues of white supremacy or racism. White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman noted that Nixon "emphasized that you have to face the fact that the whole problem is really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognized this while not appearing to."[43] With the aid of Harry Dent and South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, who had switched to the Republican Party in 1964, Richard Nixon ran his 1968 campaign on states' rights and "law and order." Liberal Northern Democrats accused Nixon of pandering to Southern whites, especially with regard to his "states' rights" and "law and order" positions, which were widely understood by black leaders to symbolize southern resistance to civil rights.[44] This tactic was described in 2007 by David Greenberg in Slate as "dog-whistle politics."[45] According to an article in The American Conservative, Nixon adviser and speechwriter Pat Buchanan disputed this characterization.[46]

The independent candidacy of George Wallace, former Democratic governor of Alabama, partially negated Nixon's Southern strategy.[47] With a much more explicit attack on integration and black civil rights, Wallace won all of Goldwater's states (except South Carolina), as well as Arkansas and one of North Carolina's electoral votes. Nixon picked up Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina and Florida, while Democratic nominee Hubert Humphrey won only Texas in the South. Writer Jeffrey Hart, who worked on the Nixon campaign as a speechwriter, said in 2006 that Nixon did not have a "Southern Strategy" but "Border State Strategy;" as he said that the 1968 campaign ceded the Deep South to George Wallace. Hart suggested that the press called it a "Southern Strategy" as they are "very lazy".[48]

In the 1972 election, by contrast, Nixon won every state in the Union except Massachusetts, winning more than 70 percent of the popular vote in most of the Deep South (Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina) and 61% of the national vote. He won more than 65 percent of the votes in the other states of the former Confederacy. Nixon won 18% of the black vote nationwide. Despite his appeal to Southern whites, Nixon was widely perceived as a moderate outside the South and won African-American votes on that basis.

Glen Moore argues that in 1970, Nixon and the Republican Party developed a "Southern Strategy" for the midterm elections. The strategy involved depicting Democratic candidates as permissive liberals. Republicans thereby managed to unseat Albert Gore, Sr., of Tennessee, as well as Senator Joseph D. Tydings of Maryland. For the entire region, however, the net result was a small loss of seats for the Republican Party in the South.[49]

Regional attention in 1970 focused on the Senate, when Nixon nominated Judge G. Harrold Carswell of Florida, a judge on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals to the Supreme Court.[50] A lawyer from north Florida, Carswell had a mediocre record, but Nixon needed a Southerner and a "strict constructionist," to support his "southern strategy" of moving the region toward the GOP. Carswell was voted down by the liberal block in the Senate, causing a backlash that pushed many Southern Democrats into the Republican fold. The long-term result was a realization by both parties that nominations to the Supreme Court could have a major impact on political attitudes In the South.[51]

In a year-by-year analysis of how the transformation took place in the critical state of Virginia, James Sweeney shows that the slow collapse of the old statewide Byrd machine gave the Republicans the opportunity to build local organizations county by county and city by city. The Democratic Party factionalized, with each faction having the goal of taking over the entire statewide Byrd machine. But the Byrd leadership was basically conservative, and more in line with the national Republican Party in economic and foreign policy issues. Republicans united behind A. Linwood Holton, Jr. in 1969, and swept the state. In the 1970 senatorial election the Byrd machine made a comeback by electing Independent Harry Flood Byrd, Jr. over Republican Ray Lucian Garland and Democrat George Rawlings. The new Senator Byrd never joined the Republican Party and instead joined the Democratic caucus. Nevertheless, he had a mostly conservative voting record especially on the trademark Byrd issue of the national deficit. At the local level, the 1970s saw steady Republican growth with this emphasis on a middle-class suburban electorate that had little interest in the historic issues of rural agrarianism and racial segregation.[52]

Evolution (1970s and 1980s)

As civil rights grew more accepted throughout the nation, basing a general election strategy on appeals to "states' rights," which some would have believed opposed civil rights laws, would have resulted in a national backlash. The concept of "states' rights" was considered by some to be subsumed within a broader meaning than simply a reference to civil rights laws.[2][3] States rights became seen as encompassing a type of New Federalism that would return local control of race relations.[53]

Republican strategist Lee Atwater discussed the Southern strategy in a 1981 interview later published in Southern Politics in the 1990s by Alexander P. Lamis.[54][55][56]

Atwater: As to the whole Southern strategy that Harry Dent and others put together in 1968, opposition to the Voting Rights Act would have been a central part of keeping the South. Now [Reagan] doesn't have to do that. All you have to do to keep the South is for Reagan to run in place on the issues he's campaigned on since 1964 . . . and that's fiscal conservatism, balancing the budget, cut taxes, you know, the whole cluster...

Questioner: But the fact is, isn't it, that Reagan does get to the Wallace voter and to the racist side of the Wallace voter by doing away with legal services, by cutting down on food stamps?

Atwater: You start out in 1954 by saying, "Nigger, nigger, nigger." By 1968 you can't say "nigger" — that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states' rights and all that stuff. You're getting so abstract now [that] you're talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you're talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I'm not saying that. But I'm saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me — because obviously sitting around saying, "We want to cut this," is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than "Nigger, nigger."

In 1980, Republican candidate Ronald Reagan made a much-noted appearance at the Neshoba County Fair.[57] His speech there contained the phrase "I believe in states' rights"[note 1] and was cited as evidence that the Republican Party was building upon the Southern strategy again.[58] Reagan's campaigns used racially coded rhetoric, making attacks on the "welfare state" and leveraging resentment towards affirmative action.[59][60] Dan Carter explains "Reagan showed that he could use coded language with the best of them, lambasting welfare queens, busing, and affirmative action as the need arose."[61] During his 1976 and 1980 campaigns Reagan employed stereotypes of welfare recipients, often invoking the case of a "welfare queen" with a large house and a Cadillac using multiple names to collect over $150,000 in tax-free income.[59][62] Aistrup described Reagan's campaign statements as "seemingly race neutral" but explained how whites interpret this in a racial manner, citing a DNC funded study conducted by CRG Communications.[59] Though Reagan didn't overtly mention the race of the welfare recipient, the unstated impression in whites' minds were black people and Reagan's rhetoric resonated with Southern white perceptions of black people.[59]

Aistrup argued one example of Reagan field-testing coded language in the South, was a reference to an unscrupulous man using food stamps as a "strapping young buck."[59][63] Reagan, when informed of the offensive connotations of the term, defended his actions as a nonracial term that was common in his Illinois hometown. Ultimately, Reagan never used that particular phrasing again.[64] According to Ian Haney Lopez the "young buck" term changed into "young fellow" which was less overtly racist. "'Some young fellow' was less overtly racist and so carried less risk of censure, and worked just as well to provoke a sense of white victimization."[65]

During the 1988 U.S. presidential election, the Willie Horton attack ads run against Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis built upon the Southern strategy in a campaign that reinforced the notion that Republicans best represent conservative whites with traditional values.[66] Lee Atwater and Roger Ailes worked on the campaign as George H. W. Bush's political strategists,[67] and upon seeing a favorable New Jersey focus group response to the Horton strategy, Atwater recognized that an implicit racial appeal could work outside of the Southern states.[68] The subsequent ads featured Horton's mugshot and played on fears of black criminals. Atwater said of the strategy, "By the time we're finished, they're going to wonder whether Willie Horton is Dukakis' running mate."[69] Al Gore was the first to use the Willie Horton prison furlough against Dukakis and, like the Bush campaign, would not mention race. The Bush campaign claimed they were initially made aware of the Horton issue via the Gore campaign's use of the subject. Bush initially hesitated to use the Horton campaign strategy, but the campaign saw it as a wedge issue to harm Dukakis who was struggling against Democratic rival Jesse Jackson.[70]

In addition to presidential campaigns, subsequent Republican campaigns for the House of Representatives and Senate in the South employed the Southern strategy. During his 1990 re-election campaign, Jesse Helms attacked his opponent's alleged support of "racial quotas," most notably through an ad in which a white person's hands are seen crumpling a letter indicating that he was denied a job because of the color of his skin.[71][72]

New York Times opinion columnist Bob Herbert wrote in 2005 that "The truth is that there was very little that was subconscious about the G.O.P.'s relentless appeal to racist whites. Tired of losing elections, it saw an opportunity to renew itself by opening its arms wide to white voters who could never forgive the Democratic Party for its support of civil rights and voting rights for blacks."[73] Aistrup described the transition of the Southern strategy saying that it has "evolved from a states’ rights, racially conservative message to one promoting in the Nixon years, vis-à-vis the courts, a racially conservative interpretation of civil rights laws—including opposition to busing. With the ascendancy of Reagan, the Southern Strategy became a national strategy that melded race, taxes, anticommunism, and religion."[74]

Some analysts viewed the 1990s as the apogee of Southernization or the Southern strategy, given that the Democratic president Bill Clinton and vice-president Al Gore were from the South, as were Congressional leaders on both sides of the aisle.[75] During the end of Nixon's presidency, the Senators representing the former Confederate states in the 93rd Congress were primarily Democrats. During the beginning of Bill Clinton's, 20 years later in the 103rd Congress, this was still the case.[76]

Shifts in strategy (1990s and 2000s)

In the mid-1990s, the Republican Party made major attempts to court African-American voters, believing that the strength of religious values within the African-American community and the growing number of affluent and middle-class African Americans would lead this group increasingly to support Republican candidates.[4][77][77] In general, these efforts did not significantly increase African-American support for the Republican Party.[4][77] Few African Americans voted for George W. Bush and other national Republican candidates in the 2004 elections, although he attracted a higher percentage of black voters than had any GOP candidate since Ronald Reagan. In his article "The Race Problematic, the Narrative of Martin Luther King Jr., and the Election of Barack Obama", Dr. Rickey Hill argued that Bush implemented his own southern strategy by exploiting "the denigration of the liberal label to convince white conservatives to vote for him. Bush's appeal was to the same racist tropes that had been used since the Goldwater and Nixon days."[78]

Following Bush's re-election, Ken Mehlman, Bush's campaign manager and Chairman of the RNC, held several large meetings in 2005 with African-American business, community, and religious leaders. In his speeches, he apologized for his party's use of the Southern Strategy in the past. When asked about the strategy of using race as an issue to build GOP dominance in the once-Democratic South, Mehlman replied,

"Republican candidates often have prospered by ignoring black voters and even by exploiting racial tensions," and, "by the '70s and into the '80s and '90s, the Democratic Party solidified its gains in the African-American community, and we Republicans did not effectively reach out. Some Republicans gave up on winning the African-American vote, looking the other way or trying to benefit politically from racial polarization. I am here today as the Republican chairman to tell you we were wrong."[79][80]

Thomas Edge argues that the election of President Barack Obama saw a new type of Southern strategy emerge among conservative voters; they used his election as evidence of a post-racial era to deny the need of continued civil rights legislation, while simultaneously playing on racial tensions and marking him as a "racial bogeyman".[81] Edge described three parts to this phenomenon saying:

"First, according to the arguments, a nation that has the ability to elect a Black president is completely free of racism. Second, attempts to continue the remedies enacted after the civil rights movement will only result in more racial discord, demagoguery, and racism against White Americans. Third, these tactics are used side-by-side with the veiled racism and coded language of the original Southern Strategy."[81]

Other observers have suggested that the election of President Obama in the 2008 presidential election and subsequent re-election in 2012 signaled the growing irrelevance of the southern strategy-style tactics. Louisiana State University political scientists Wayne Parent, for example, suggested that Obama's ability to get elected without the support of southern states demonstrate that the regions was moving from "the center of the political universe to being an outside player in presidential politics,"[75] while University of Maryland, Baltimore County political scientist Thomas Schaller argued that the Republican party had "marginalized" itself, becoming a "mostly regional party" through a process of Southernization.[75]

Scholarly debates

Scholars generally emphasize the role of racial backlash in the realignment of southern voters. The viewpoint that the electoral realignment of the Republican party due to a race-driven Southern Strategy is also known as the "top-down" viewpoint.[5][7] Most scholarship and analysts support this top-down viewpoint and claim that the political shift was due primarily to racial issues.[7][82][83] The Southern Strategy is generally believed to be the primary force that transformed the "Democratic South into a reliable GOP stronghold in presidential elections."[6] Some historians believe that racial issues took a back seat to a grassroots narrative known as the "suburban strategy". Matthew Lassiter, who along with Shafer and Johnston is a leading proponent of the "suburban strategy" viewpoint, recognizes "This analysis runs contrary to both the conventional wisdom and a popular strain in the scholarly literature...."[84] Glen Feldman, when speaking of the "suburban strategy", states it is "the dissenting – yet rapidly growing – narrative on the topic of southern partisan realignment..."[10]

Matthew Lassiter says, "A suburban-centered vision reveals that demographic change played a more important role than racial demagoguery in the emergence of a two-party system in the American South."[85] Lassiter argues that race-based appeals can't explain the GOP shift in the south while also noting that the real situation is far more complex.[86]

Kalk and Tindall separately argue that Nixon's Southern strategy was to find a compromise that on race would take the issue house of politics, allowing conservatives in the South to rally behind his grand plan to reorganize the national government. Kalk and Tindall emphasize the similarity between Nixon's operations and the series of compromises orchestrated by Rutherford B Hayes in 1877 that ended the battles over Reconstruction and put Hayes in the White House. Kalk says Nixon did end the reform impulse and sowed the seeds for the political rise of white Southerners and the decline of the civil rights movement.[87][88]

Kotlowski argues that Nixon's overall civil rights record was, on the whole, responsible and that Nixon tended to seek the middle ground. He campaigned as a moderate in 1968, pitching his appeal to the widest range of voters. Furthermore, he continued this strategy as president. As a matter of principle, says Kotlowski, he supported integration of schools. However Nixon chose not to antagonize Southerners who opposed it, and left enforcement to the judiciary, which had originated the issue in the first place.[89][90] In particular Kotlowski believes historians have been somewhat misled by Nixon's rhetorical Southern Strategy that had limited influence on actual policies.[91] Valentino and Sears state that other scholars downplay the role of racial prejudice even in contemporary racial politics. They write:

- A quarter century ago, what counted was who a policy would benefit, blacks or whites" (Sniderman and Piazza 1993, 4-5), while "the contemporary debate over racial policy is driven primarily by conflict over what the government should try to do, and only secondarily over what it should try to do for blacks" [emphasis in original], so "prejudice is very far from a dominating factor in the contemporary politics of race." (Sniderman and Carmines 1997, 4, 73)[92]

Valentino and Sears conducted their own study and reported that "the South's shift to the Republican party has been driven to a significant degree by racial conservatism" and also concluded that "racial conservatism seems to continue to be central to the realignment of Southern whites' partisanship since the Civil Rights era".[92]

Political scientists and historians point out, that the timing does not fit the "Southern strategy" model. Nixon carried 49 states in 1972, so he operated a successful national rather than regional strategy. but the Republican Party remained quite weak at the local, and state level across the entire South for decades. Matthew Lassiter argues that Nixon's appeal was not to the Wallacites or segregationists, but rather to the rapidly emerging suburban middle-class. Many had Northern antecedents; they wanted rapid economic growth and saw the need to put backlash politics to rest. Lassiter says the Southern strategy was a "failure" for the GOP and that the southern base of the Republican Party "always depended more on the middle-class corporate economy and on the top-down politics of racial backlash." Furthermore, realignment in the South "came primarily from the suburban ethos of New South metropolises such as Atlanta and Charlotte, North Carolina, not to the exportation of the working-class racial politics of the Black Belt."[93]

Mayer argues that scholars have given too much emphasis on the civil rights issue; it was not the only deciding factor for Southern white voters. Goldwater took positions on such issues as privatizing the Tennessee Valley Authority, abolishing Social Security, and ending farm price supports that outraged many white Southerners who strongly supported these programs. Mayer states:

- Goldwater's staff also realized that his radical plan to sell the Tennessee Valley Authority was causing even racist whites to vote for Johnson. A Florida editorial urged Southern whites not to support Goldwater even if they agreed with his position on civil rights, because his other positions would have grave economic consequences for the region. Goldwater's opposition to most poverty programs, the TVA, aid to education, Social Security, the Rural Electrification Administration, and farm price supports surely cost him votes throughout the South and the nation.[94]

Political scientist Nelson W. Polsby argued that economic development was more central than racial desegregation in the evolution of the postwar South in Congress.[95] In The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South the British political scientist Byron E. Shafer and the Canadian Richard Johnston, developed the Polsby the argument in greater depth. Using roll call analysis of voting patterns in the House of Representatives, they found that Issues of desegregation and race were less important than issues of economics and social class when it came to the transformation of partisanship in the South.[96] This view is backed by Glenn Feldman who notes that the early narratives on the southern realignment focused on the idea of appealing to racism. This argument was first and thus took hold as the accepted narrative. He notes, however, that Lassiter's dissenting view on this subject, a view that the realignment was a "suburban strategy" rather than a "southern strategy" was just one of the first of a rapidly growing list of scholars who see the civil rights, "white backlash" as a secondary or minor factor. Authors such as Tim Boyd, George Lewis, Michael Bowen, and John W. White follow the lead of Lassiter, Shafer and Johnston in viewing suburban voters and their self interests as the primary reason for the realignment. He doesn't discount race as part of the motivation of these suburban voters who were fleeing urban crime and school busing.[10]

Gareth Davies argues that "[t]he scholarship of those who emphasize the southern strategizing Nixon is not so much wrong – it captures one side of the man – as it is unsophisticated and incomplete. Nixon and his enemies needed one another in order to get the job done."[97][98] Lawrence McAndrews makes a similar argument, saying Nixon pursued a mixed strategy:

- Some scholars claim that Nixon succeeded, by leading a principled assault on de jure school desegregation. Others claim that he failed, by orchestrating a politically expedient surrender to de facto school segregation. A close examination of the evidence, however, reveals that in the area of school desegregation, Nixon's record was a mixture of principle and politics, progress and paralysis, success and failure. In the end, he was neither simply the cowardly architect of a racially insensitive "Southern strategy" which condoned segregation, nor the courageous conductor of a politically risky "not-so-Southern strategy" which condemned it.[99]

In interviews with historians years later, Nixon denied that he ever practiced a Southern strategy. Harry Dent, one of Nixon's senior advisers on Southern politics, told Nixon privately in 1969 that the administration "has no Southern strategy, but rather a national strategy which, for the first time in modern times, includes the South."[100]

See also

- Bible Belt

- Conservative Coalition

- Political culture of the United States

- Politics of the Southern United States

- Racism in the United States

- Solid South

Notes

- ↑ Quoted from Reagan's speech: I still believe the answer to any problem lies with the people. I believe in states' rights and I believe in people doing as much as they can for themselves at the community level and at the private level. I believe we have distorted the balance of our government today by giving powers that were never intended to be given in the Constitution to that federal establishment. "Sound file" (MP3). Onlinemadison.com. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

References

- 1 2 Boyd, James (May 17, 1970). "Nixon's Southern strategy: 'It's All in the Charts'" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- 1 2 Carter, Dan T. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963–1994. p 35

- 1 2 3 Branch, Taylor (1999). Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963–65. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 242. ISBN 0-684-80819-6. OCLC 37909869.

- 1 2 3 4 Apple, R.W. Jr. (September 19, 1996). "G.O.P. Tries Hard to Win Black Votes, but Recent History Works Against It". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

- 1 2 Aistrup, Joseph A. (1996). The Southern Strategy Revisited: Republican Top-Down Advancement in the South. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-4792-1.

- 1 2 Lisa Bedolla, Kerry Haynie (2013). The Obama coalition and the future of American politics. Politics, Groups, and Identities. Rutledge. pp. 128–133.

- 1 2 3 Lassiter, Matthew D. (2006). The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. Princeton University Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-1-4008-4942-0.

- ↑ Julian E. Zelizer (4 March 2012). Governing America: The Revival of Political History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1-4008-4189-5.

younger Southern historians such as Matthew Lassiter, Kevin Kruse, and Joseph Crespino objected to claims about Southern Exceptionalism while agreeing on the centrality of a racial backlash

- ↑ Lassiter, Matthew D. (2006). The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. Princeton University Press. pp. 4–7. ISBN 978-1-4008-4942-0.

- 1 2 3 Feldman, Glenn (2011). Painting Dixie Red: When, Where, Why and How the South Became Republican. University Press of Florida. pp. 16, 80.

- ↑ Matthew D. Lassiter; Joseph Crespino (2010). The Myth of Southern Exceptionalism. Oxford University Press. pp. 25–. ISBN 978-0-19-538474-1.

- ↑ Kevin Michael Kruse (2005). White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09260-5.

- ↑ Rondy, John (July 15, 2005). "GOP ignored black vote, chairman says: RNC head apologizes at NAACP meeting". The Boston Globe. Reuters. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

- ↑ Allen, Mike (July 14, 2005). "RNC Chief to Say It Was 'Wrong' to Exploit Racial Conflict for Votes". Washington Post. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ↑ Javits, Jacob K. (October 27, 1963). "To Preserve the Two-Party System". The New York Times.

- ↑ Phillips, Kevin (1969). The Emerging Republican Majority. New York: Arlington House. ISBN 0-87000-058-6. OCLC 18063. passim

- ↑ Richard H. Abbott, The Republican Party and the South, 1855–1877: The First Southern Strategy (1986) p. 231

- ↑ Tali Mendelberg (2001). The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages, and the Norm of Equality. Princeton UP. p. 52.

- ↑ C. Vann Woodward, Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction(1956) p 8, 205-12

- ↑ Vincent P. De Santis, Republicans face the southern question: The new departure years, 1877–1897 (1959) pp 71-85

- ↑ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War (New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux, 2007), pp.74-80

- ↑ Zinn, Howard (1999). A People's History of the United States. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 205–210, 449. ISBN 0-06-052842-7.

- ↑ Perman, Michael (2001). Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp 1-8

- ↑ "Turnout for Presidential and Midterm Elections". Politics: Historical Barriers to Voting. University of Texas. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008.

- ↑ Boris Heersink and Jeffery A. Jenkins, "Southern Delegates and Republican National Convention Politics, 1880–1928," Studies in American Political Development (April 2015) 29#1 pp 68-88

- ↑ Edward O. Frantz, The Door of Hope: Republican Presidents and the First Southern Strategy, 1877–1933 (University Press of Florida, 2011)

- ↑ "Beginnings of black education", The Civil Rights Movement in Virginia. Virginia Historical Society. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- ↑ Dobbs, Ricky Floyd (January 1, 2007). "Continuities in American anti-Catholicism: the Texas Baptist Standard and the coming of the 1960 election.". Baptist History and Heritage. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

- ↑ "Thurmond to Bolt Democrats Today; South Carolinian Will Join G.O.P. and Aid Goldwater". The New York Times. September 16, 1964. p. 12. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

Both senators have opposed the Administration on such matters as civil rights...

- ↑ Benen, Steve (May 21, 2010). "The Party of Civil Rights". Washington Monthly. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ↑ Gregg, Khyree. "The Second Great Migration". inmotionaame. inmotionaame. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ James L. Sundquist (2011). Dynamics of the Party System: Alignment and Realignment of Political Parties in the United States. Brookings Institution Press. p. 285.

- ↑ G黱ter·Bischof and Stephen E. Ambrose, eds. (1995). Eisenhower: A Centenary Assessment. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Sheldon Goldman (1999). Picking Federal Judges: Lower Court Selection from Roosevelt Through Reagan. Yale University Press. p. 128.

- 1 2 McWhorter, Diane (2001). Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama, The Climactic Battle of the Civil Rights Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80747-5. OCLC 45376386.

- ↑ Robert H Donaldson (2015). Liberalism's Last Hurrah: The Presidential Campaign of 1964. Taylor & Francis. p. 27.

- 1 2 "Civil Rights Act of 1964 – CRA – Title VII – Equal Employment Opportunities – 42 US Code Chapter 21". Finduslaw.com. Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- ↑ Gregg, Khyree. "Election of 1964". American Presidency Project. American Presidency Project. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ Rutenberg, Jim (29 July 2015). "A Dream Undone". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ Risen, Clay (March 5, 2006). "How the South was won". (subscription required) The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-02-11

Thomas R. Dye, Louis Schubert, Harmon Zeigler. The Irony of Democracy: An Uncommon Introduction to American Politics, Cengage Learning. 2011

Ted Van Dyk. "How the Election of 1968 Reshaped the Democratic Party", Wall Street Journal, 2008 - ↑ Zinn, Howard (1999) A People's History of the United States New York:HarperCollins, 457-461

- ↑ Zinn, Howard (1999) A People's History of the United States New York:HarperCollins, 491

- ↑ Robin, Corey (2011). The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism from Edmund Burke to Sarah Palin. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 0-19-979393-X.

- ↑ Johnson, Thomas A. (August 13, 1968). "Negro Leaders See Bias in Call Of Nixon for 'Law and Order'". The New York Times. p. 27. Retrieved 2008-08-02.(subscription required)

- ↑ Greenberg, David (November 20, 2007). "Dog-Whistling Dixie: When Reagan said "states' rights," he was talking about race.". Slate. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

- ↑ "Nixon in Dixie", The American Conservative magazine

- ↑ Childs, Marquis (June 8, 1970). "Wallace's Victory Weakens Nixon's Southern Strategy". The Morning Record.

- ↑ Hart, Jeffrey (2006-02-09). The Making of the American Conservative Mind (television). Hanover, New Hampshire: C-SPAN.

- ↑ Glen Moore, "Richard M. Nixon and the 1970 Midterm Elections in the South." Southern Historian 12 (1991) pp: 60-71.

- ↑ John Paul Hill, "Nixon's Southern Strategy Rebuffed: Senator Marlow W. Cook and the Defeat of Judge G. Harrold Carswell for the US Supreme Court." Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 112#4 (2014): 613-650.

- ↑ Bruce H. Kalk, "The Carswell Affair: The Politics of a Supreme Court Nomination in the Nixon Administration." American Journal of Legal History (1998): 261-287. in JSTOR

- ↑ James R. Sweeney, "Southern strategies," Virginia Magazine of History & Biography (1998) 106#2 pp 165-200.

- ↑ Aistrup, Joseph A. (2015). The Southern Strategy Revisited: Republican Top-Down Advancement in the South. University Press of Kentucky. p. 48. ISBN 0-8131-4792-1.

- ↑ Lamis, Alexander P. (1999). Southern Politics in the 1990s. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-8071-2374-4.

- ↑ "The Persuadable Voter". google.com.

- ↑ Rick Perlstein (13 November 2012). "Exclusive: Lee Atwater's Infamous 1981 Interview on the Southern Strategy". The Nation.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan's Neshoba County Speech". C-SPAN. C-SPAN. April 10, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ↑ Cannon, Lou (2003). Governor Reagan: His Rise to Power, New York: Public Affairs, 477-78.

Michael Goldfield (1997) The Color of Politics: Race and the Mainspring of American Politics, New York: The New Press, 314.

Walton, Hanes (1997). African American Power and Politics. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-231-10419-7. - 1 2 3 4 5 Aistrup, Joseph A. (2015). The Southern Strategy Revisited: Republican Top-Down Advancement in the South. University Press of Kentucky. p. 44. ISBN 0-8131-4792-1.

- ↑ Henry A. Giroux (2002). "Living dangerously: Identity politics and the new cultural racism: Towards a critical pedagogy of representation". Routledge: 38.

- ↑ Dan T. Carter (24 February 1999). From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963--1994. Louisiana State University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-8071-2366-9.

- ↑ "The Truth Behind The Lies Of The Original 'Welfare Queen'". NPR.org. 20 December 2013.

- ↑ Haney-Lopez, Ian (January 13, 2014). Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class. Oxford University Press.

Reagan also trumpeted his racial appeals in blasts against welfare cheats. On the stump, Reagan repeatedly invoked a story of a “Chicago welfare queen” with “eighty names, thirty addresses, [and] twelve Social Security cards [who] is collecting veteran’s benefits on four non-existing deceased husbands. She’s got Medicaid, getting food stamps, and she is collecting welfare under each of her names. Her tax-free cash income is over $150,000.”

- ↑ Mayer, Jermey D (2002). Running on Race: Racial Politics in Presidential Campaigns, 1960–2000. Random House Inc. pp. 152–155.

- ↑ Haney-Lopez, Ian (January 13, 2014). Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Aistrup, Joseph A. (2015). The Southern Strategy Revisited: Republican Top-Down Advancement in the South. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-8131-4792-1.

- ↑ Swint, Kerwin (2008). Dark Genius: The Influential Career of Legendary Political Operative and Fox News Founder Roger Ailes. New York: Union Square Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 1-4027-5445-0.

- ↑ Mendelberg, Tali (2001). The Race Card: Campaign Strategy, Implicit Messages, and the Norm of Equality. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 143–144. ISBN 0-691-07071-7.

- ↑ Whitaker, Morgan (October 21, 2013). "The legacy of the Willie Horton ad lives on, 25 years later". MSNBC.

- ↑ Mayer, Jermey D (2002). Running on Race: Racial Politics in Presidential Campaigns, 1960–2000. Random House Inc. pp. 212–214.

- ↑ Jesse Helms "Hands" ad. 16 October 2006 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Caliendo, Stephen Maynard; McIlwain, Charlton D. (2005). "Racial Messages in Political Campaigns". Polling America: An Encyclopedia of Public Opinion. 2. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 643. ISBN 0-313-32713-0.

- ↑ Herbert, Bob (October 6, 2005). "Impossible, Ridiculous, Repugnant". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

- ↑ Aistrup, Joseph A. The Southern Strategy Revisited: Republican Top-down Advancement in the South University Press of Kentucky, 1996

- 1 2 3 Nossiter, Adam (November 10, 2008). "For South, a Waning Hold on National Politics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012.

- ↑ Alexander P. Lamis, ed., Southern Politics in the 1990s (1999) pp 1-9

- 1 2 3 African-American voting trends Facts on File.com

- ↑ Hill, Ricky (March 2009). "The Race Problematic, the Narrative of Martin Luther King Jr., and the Election of Barack Obama" (PDF). Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society. 11 (1): 133–147.

- ↑ Allen, Mike (July 14, 2005). "RNC Chief to Say It Was 'Wrong' to Exploit Racial Conflict for Votes". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 22, 2012. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- ↑ Benedetto, Richard (July 14, 2005). "GOP: 'We were wrong' to play racial politics". USA Today. Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- 1 2 Edge, Thomas (January 2010). "Southern Strategy 2.0: Conservatives, White Voters, and the Election of Barack Obama". Journal of Black Studies. 40 (3): 426–444. doi:10.1177/0021934709352979. JSTOR 40648600.

- ↑ Frymer, Paul; Skrentny, John David (1998). "Coalition-Building and the Politics of Electoral Capture During the Nixon Administration: African Americans, Labor, Latinos" (PDF). Studies in American Political Development. Cambridge University Press. 12.: 132 in 131–161. doi:10.1017/s0898588x9800131x.

- ↑ Boyd, Tim D. (2009). "The 1966 Election in Georgia and the Ambiguity of the White Backlash". The Journal of Southern History: 305–340. JSTOR 27778938.

- ↑ Lassiter, Matthew; Kruse, Kevin (Aug 2009). "The Bulldozer Revolution: Suburbs and Southern History since World War II". The Journal of Southern History. 75: 699. JSTOR 27779033.

- ↑ Lassiter, Matthew; Kruse, Kevin (Aug 2009). "The Bulldozer Revolution: Suburbs and Southern History since World War II". The Journal of Southern History. 75: 699. JSTOR 27779033.

Alexander, Gerard (Sep 12, 2010). "Conservatism does not equal racism. So why do many liberals assume it does?". Washington Post. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

Alexander, Gerard (March 20, 2004). "The Myth of the Racist Republicans". The Claremont Review of Books. 4 (2). Retrieved March 25, 2015. - ↑ Lassiter, Matthew (2007). The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. Princeton University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-691-13389-8.

Chappell, David (March 2007). "Did Racists Create the Suburban Nation?". Reviews in American History. V 35: 89–97.Lassiter scrupulously denies suburbanites their racial innocence. The suburbs are disproportionately white and the poor are disproportionately black. But he rejects “white backlash” partly because the term exempts from responsibility those voters, North and South, who have racially liberal roots. Their egalitarianism may be genuine. But unless liberals are lucky enough to live in secession-proof metro areas, whose judges have a strong commitment to comprehensive integration, they behave the same way as people who act frankly on their fear of large concentrations of black people.

Chappell, David (March 2007). "Did Racists Create the Suburban Nation?". Reviews in American History. Johns Hopkins University Press. V 35: 89–97.In an original analysis of national politics, Lassiter carefully rejects “racereductionist narratives” (pp. 4, 303). Cliches like “white backlash” and “southern strategy” are inadequate to explain the conservative turn in post-1960s politics.5 … Racism has not been overcome. One might say rather that it has become redundant. One of Lassiter’s many fascinating demonstrations of racism’s superfluousness is his recounting of the actual use of the “southern strategy.” The strategy obviously failed the Dixiecrats in l948 and the GOP in l964. The only time Nixon seriously tried to appeal to southern racism, in the l970 midterm elections, the South rejected his party and elected Democrats like Jimmy Carter and Dale Bumpers instead (pp. 264–74). To win a nationwide majority, Republicans and Democrats alike had to appeal to the broad middle-class privileges that most people believed they had earned. Lassiter suggests that the first step on the way out of hypersegregation and resegregation is to stop indulging in comforting narratives. The most comforting narratives attribute the whole problem to racists and the Republicans who appease them.

Lassiter, Matthew; Kruse, Kevin (Aug 2009). "The Bulldozer Revolution: Suburbs and Southern History since World War II". The Journal of Southern History. 75: 691–706. JSTOR 27779033. - ↑ Bruce H. Kalk, "Wormley's Hotel Revisited: Richard Nixon's Southern Strategy and the End of the Second Reconstruction," North Carolina Historical Review (1994) 71#1 pp. 85-105 in JSTOR

- ↑ George B. Tindall, "Southern Strategy: A Historical Perspective," North Carolina Historical Review (1971) 48#2 pp. 126-141 in JSTOR

- ↑ Dean J. Kotlowski, "Nixon's southern strategy revisited." Journal of Policy History (1998) 10#2 pp: 207-238.

- ↑ Kotlowski, Dean (2009). Nixon's Civil Rights: Politics Principle, and Policy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03973-5.

- ↑ Aldridge, Daniel (Summer 2002). "Review". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 86.

- 1 2 Valentino NA, Sears DO (2005). "Old Times There Are Not Forgotten: Race and Partisan Realignment in the Contemporary South" (PDF). American Journal of Political Science. 49: 672–688. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00136.x.

- ↑ Matthew D. Lassiter, "Suburban Strategies: The Volatile Center in Postwar American Politics" in Meg Jacobs et al. eds., The Democratic Experiment: New Directions In American Political History (2003): 327-349; quotes on pp 329-30.

- ↑ Jeremy D. Mayer, "LBJ Fights the White Backlash: The Racial Politics of the 1964 Presidential Campaign, Part 2 " Prologue 33#2 (2001) pp: 6-19.

- ↑ Byron E. Shafer and Richard Johnston, The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South (Harvard University Press, 2006) p vii

- ↑ Byron E. Shafer and Richard G.C. Johnston. "The transformation of southern politics revisited: The House of Representatives as a window." British Journal of Political Science (2001) 31#4 pp: 601-625. In their 2006 book they write, "economics and social class clearly trumped desegregation and racial identity as engines for partisan change." Shafer and Johnston, The End of Southern Exceptionalism p vii

- ↑ Gareth Davies, See Government Grow: Education Politics from Johnson to Reagan (2007) p 140).

- ↑ Gareth Davies, "Richard Nixon and the Desegregation of Southern Schools." Journal of Policy History 19#04 (2007) pp: 367-394.

- ↑ Lawrence J. McAndrews, "The politics of principle: Richard Nixon and school desegregation." Journal of Negro History (1998): 187-200, quoting page 187. in JSTOR

- ↑ Joan Hoff (1995). Nixon Reconsidered. BasicBooks. p. 79.

Further reading

- Aistrup, Joseph A. "Constituency diversity and party competition: A county and state level analysis." Political Research Quarterly 57#2 (2004): 267-281.

- Aistrup, Joseph A. The southern strategy revisited: Republican top-down advancement in the South (University Press of Kentucky, 2015)

- Aldrich, John H. "Southern Parties in State and Nation" Journal of Politics 62#3 (2000) pp: 643-670.

- Applebome, Peter. Dixie Rising: How the South is Shaping American Values, Politics, and Culture (ISBN 0-15-600550-6).

- Bass, Jack. The transformation of southern politics: Social change and political consequence since 1945 (University of Georgia Press, 1995)

- Black, Earl and Merle Black. The Rise of Southern Republicans (Harvard University Press, 2003)

- Brady, David, Benjamin Sosnaud, and Steven M. Frenk. "The shifting and diverging white working class in US presidential elections, 1972–2004." 'Social Science Research 38.1 (2009): 118-133.

- Brewer, Mark D., and Jeffrey M. Stonecash. "Class, race issues, and declining white support for the Democratic Party in the South." Political Behavior 23#2 (2001): 131-155.

- Bullock III, Charles S. and Mark J. Rozell, eds. The New Politics of the Old South: An Introduction to Southern Politics (5th ed. 2013)

- Carter, Dan T. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963–1994 (ISBN 0-8071-2366-8)

- Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, The Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of Southern Politics (ISBN 0-8071-2597-0)

- Chappell, David L. A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow (ISBN 0-8078-2819-X)

- Davies, Gareth. "Richard Nixon and the Desegregation of Southern Schools." Journal of Policy History 19#04 (2007) pp: 367-394.

- Egerton, John. "A Mind to Stay Here: Closing Conference Comments on Southern Exceptionalism", Southern Spaces, 29 November 2006.

- Frantz, Edward O. The Door of Hope: Republican Presidents and the First Southern Strategy, 1877–1933 (University Press of Florida, 2011)

- Havard, William C., ed. The Changing Politics of the South (Louisiana State University Press, 1972)

- Hill, John Paul. "Nixon's Southern Strategy Rebuffed: Senator Marlow W. Cook and the Defeat of Judge G. Harrold Carswell for the US Supreme Court." Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 112#4 (2014): 613-650.

- Inwood, Joshua F.J. "Neoliberal racism: the ‘Southern Strategy’ and the expanding geographies of white supremacy." Social & Cultural Geography 16#4 (2015) pp: 407-423.

- Kalk, Bruce H. The Origins of the Southern Strategy: Two-party Competition in South Carolina, 1950–1972 (Lexington Books, 2001)

- Kalk, Bruce H. "Wormley's Hotel Revisited: Richard Nixon's Southern Strategy and the End of the Second Reconstruction." North Carolina Historical Review (1994): 85-105. in JSTOR

- Kalk, Bruce H. The Machiavellian nominations: Richard Nixon's Southern strategy and the struggle for the Supreme Court, 1968–70 (1992)

- Kruse, Kevin M. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (ISBN 0-691-09260-5)

- Lisio, Donald J. Hoover, Blacks, and Lily-Whites: A Study of Southern Strategies (UNC Press, 2012)

- Lublin, David. The Republican South: Democratization and Partisan Change (Princeton University Press, 2004)

- Olien, Roger M. From Token to Triumph: The Texas Republicans, 1920–1978 (SMU Press, 1982)

- Perlstein, Rick. Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America (2009)

- Phillips, Kevin. The Emerging Republican Majority (1969) (ISBN 0-87000-058-6)

- Boyd, James. "Nixon's Southern strategy 'It's All In the Charts'", New York Times, May 17, 1970

- Scher, Richard K. Politics in the New South: Republicanism, race and leadership in the twentieth century (1992)

- Shafer, Byron E., and Richard Johnston. The end of Southern exceptionalism: class, race, and partisan change in the postwar South (Harvard University Press, 2009)

- Shafer, Byron E., and Richard G.C. Johnston. "The transformation of southern politics revisited: The House of Representatives as a window." British Journal of Political Science 31#04 (2001): 601-625. online