The Snake Pit

| The Snake Pit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Anatole Litvak |

| Produced by |

Robert Bassler Anatole Litvak Darryl F. Zanuck |

| Screenplay by |

Frank Partos Millen Brand Arthur Laurents (uncredited) |

| Based on |

The Snake Pit by Mary Jane Ward |

| Starring |

Olivia de Havilland Mark Stevens Leo Genn Celeste Holm |

| Music by | Alfred Newman |

| Cinematography | Leo Tover |

| Edited by | Dorothy Spencer |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates | November 4, 1948 |

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $3.8 million[1] |

| Box office | $4.1 million (US/Canada rentals) [2] |

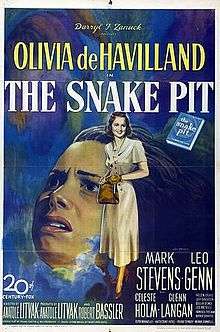

The Snake Pit is a 1948 American drama film directed by Anatole Litvak and stars Olivia de Havilland, Mark Stevens, Leo Genn, Celeste Holm, Beulah Bondi, and Lee Patrick.[3][4] Based on Mary Jane Ward's 1946 semi-autobiographical novel of the same name, the film tells the story of a woman who finds herself in an insane asylum and cannot remember how she got there.

The novel was adapted for the screen by Frank Partos and Millen Brand, in screen credits order, and Arthur Laurents (uncredited).

Plot

Virginia Cunningham (Olivia de Havilland) is an apparently schizophrenic inmate at a mental institution called the Juniper Hill State Hospital (which treats only female patients). She hears voices and seems so out of touch with reality that she doesn’t recognize her husband Robert (Mark Stevens).

Dr. Kik (Leo Genn; as Mark Van Kensdelaerik, MD/"Dr. Kik") works with her, and flashbacks show how Virginia and Robert met a few years earlier in Chicago. He worked for a publisher who rejected her writing, and they bumped into each other again in the cafeteria. Occasionally she continued to drop by the cafeteria so they get to know each other.

Despite their blossoming romance, Virginia eventually abruptly leaves town without explanation. Robert moves to New York and bumps into her again at the Philharmonic. After she provides a loose excuse for her absence and departure, they pick up where they left off, though she remains evasive and avoids his desire for marriage. Eventually, Virginia brings up the possibility of marriage. They marry on May 7, but Virginia acts erratically again. She can’t sleep and loses touch with reality, as she feels it is November and snaps when Robert corrects her. The rest of the film follows her therapy. Dr. Kik puts her through electro-shock treatment and other forms of treatment including hypnotherapy. Dr. Kik wants to get to the "causes of her unconscious rejection." The film includes many flashbacks, including her earlier failed engagement to Gordon (Leif Erickson) as well as childhood issues. The film shows her progress and what happens to her along the way.

The mental hospital is organized on a spectrum of "levels." The better a patient gets, the lower level she is able to achieve. Virginia moves to the lowest level (One), where she encounters Nurse Davis (Helen Craig), the only truly abusive nurse in the hospital. Davis is jealous of Dr. Kik's interest in Virginia, which she sees as excessive. Nurse Davis goads Virginia into an outburst which results in Virginia being straightjacketed and expelled from Level One into the "snake pit," where patients considered beyond help are simply placed together in a large padded cell and abandoned. Dr. Kik, learning of this, has Virginia returned to Level One, but away from Nurse Davis's care.

Despite this setback, Dr. Kik's care continues to improve Virginia's mental state. Over time, Virginia gains insight and self-understanding, and is able to leave the hospital.

The film also depicts the bureaucratic regimentation of the institution, the staff—some unkind and aloof, some kind and empathetic—and relationships between patients, from which Virginia learns as much as she does in therapy.

Cast

| Actor/Actress | Character |

|---|---|

| Olivia de Havilland | Virginia Stuart Cunningham |

| Mark Stevens | Robert Cunningham |

| Leo Genn | Dr. Mark H. Van Kensdelaerik/"Dr. Kik"[5] |

| Celeste Holm | Grace |

| Glenn Langan | Dr. Terry |

| Helen Craig | Nurse Davis |

| Leif Erickson | Gordon |

| Beulah Bondi | Mrs. Greer |

| Lee Patrick | Asylum Inmate |

| Howard Freeman | Dr. Curtis |

| Natalie Schafer | Mrs. Stuart |

| Ruth Donnelly | Ruth |

| Katherine Locke | Margaret |

| Celia Lovsky | Gertrude |

| Frank Conroy | Dr. Jonathan Gifford |

| Minna Gombell | Miss Hart |

| Betsy Blair | Hester |

Production

Gene Tierney was the first choice to play Virginia Stuart Cunningham, but was replaced by Olivia de Havilland when Tierney became pregnant.

Director Anatole Litvak insisted upon three months of grueling research. He demanded that the entire cast and crew accompany him to various mental institutions and to lectures by leading psychiatrists. He did not have to convince Olivia de Havilland who threw herself into the research with an intensity that surprised even those who knew her well. She watched carefully each of the procedures then in vogue, including hydrotherapy and electric shock treatments. When permitted, she sat in on long individual therapy sessions. She attended social functions, including dinners and dances with the patients. In fact, when, after the film's release, columnist Florabel Muir questioned in print whether any mental institution actually "allowed contact dances among violent inmates," she was surprised by a telephone call from de Havilland, who assured her she had attended several such dances herself.[6] Much of the film was filmed in the Camarillo State Mental Hospital in California.

Litvak, an early adopter, and master of the whip pan scene transition device, used the whip pan no less than eight times in this film.

Reception

The critics were generally kind, with Louella Parsons declaring: "It is the most courageous subject ever attempted on the screen". Walter Winchell wrote: "Its seething quality gets inside of you." On the other hand, Herman F. Weinberg, a noted psychiatrist, was unimpressed. He wrote, "A film of superficial veracity that requires a bigger man than Litvak; a good film with bad things in it."[7]

The film has come under fire from some women's rights authors for a seeming misportrayal of Virginia's difficulties and the implication that accepting a subservient role as a wife and mother is part of her "cure".[8] Other film analysts view it as successful in conveying Ward's view of the uncertainties of post-World War II life and women's roles.[9]

Censorship

Due to public concerns that the extras in the film were in fact real mental patients being exploited, the British censor added a foreword explaining that everyone who appeared on screen was a paid actor and that conditions in British hospitals were unlike those portrayed in the film.[7]

Awards

It won the Academy Award for Best Sound Recording (Thomas T. Moulton), and was nominated for Best Actress in a Leading Role (Olivia de Havilland), Best Director, Best Music, Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture, Best Picture and Best Writing, Screenplay.[10]

The film also won the International Prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1949, where it was cited for "a daring inquiry in a clinical case dramatically performed."[7]

Impact

The film led to changes in the conditions of mental institutions in the United States. In 1949, Herb Stein of Daily Variety wrote "Wisconsin is the seventh state to institute reforms in its mental hospitals as a result of The Snake Pit.[11]

Publicity releases from 20th Century Fox claimed that twenty-six of the then forty-eight states had enacted reform legislation because of the movie. This is a very difficult claim to verify because few of the bills introduced, regulations changed or funding increases implemented specifically mentioned The Snake Pit as a motivating factor.[11]

Other adaptations

The Snake Pit was dramatized as an hour-long radio play on the April 10, 1950 broadcast of Lux Radio Theater, with de Havilland reprising her film role.

See also

References

- ↑ Variety January 1949

- ↑ "All-Time Top Grossers", Variety, 8 January 1964, p. 69

- ↑ Variety film review; November 3, 1948, page 11.

- ↑ Harrison's Reports film review; November 6, 1948, page 179.

- ↑ Dr. Kik is never referred to by his family name.

- ↑ Clooney, p. 141

- 1 2 3 Clooney, Nick (November 2002). The Movies That Changed Us: Reflections on the Screen. New York: Atria Books, a trademark of Simon & Schuster. p. 143. ISBN 0-7434-1043-2.

- ↑ Fishbein, Leslie, "The Snake Pit (1948): The Sexist Nature of Sanity," American Quarterly 31: 5 (1979): 641-655.

- ↑ Harris, Ben. "Arthur Laurents' Snake Pit: Populist Entertainment in Post-WWII America." Paper presented at the annual meeting of The American Studies Association, Philadelphia Marriott Downtown, Philadelphia, PA, Oct 11, 2007, abstract found 2008-09-13.

- ↑ "The 21st Academy Awards (1949) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- 1 2 Clooney, p. 144

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Snake Pit. |

- The Snake Pit at the Internet Movie Database

- The Snake Pit at the TCM Movie Database

- The Snake Pit at AllMovie

- Review of The Snake Pit at TVGuide.com