USS PC-598

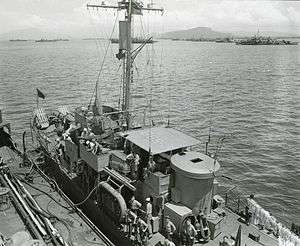

PC-598 at Humboldt Bay, New Guinea - October 1944. (Howard F. Klawitter, U.S. Army) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | USS PC-598 |

| Builder: | Commercial Iron Works Portland, OR |

| Laid down: | 23 May 1942 |

| Launched: | 7 September 1942 |

| Commissioned: | 5 March 1943 |

| Decommissioned: | Decommissioned and laid up at the Tongue Point Reserve Fleet, Kilisut Harbor, Port Townsend, WA |

| Honors and awards: | PC-598 served as an amphibious landing control craft at four major invasions (Peleliu, Leyte, Luzon and Okinawa) and two amphibious landings (Iheya Shima and Aguni Shima.) |

| Fate: | Sold 29 November 1946 to the Foss Tug and Barge Co., of Tacoma, WA. Fate unknown. |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | PC-461-class submarine chaser |

| Displacement: | 295 tons fully loaded |

| Length: | 173 ft (53 m) |

| Beam: | 23 ft (7.0 m) |

| Draft: | 10 ft 10 in (3.30 m) |

| Propulsion: | Two 1,440bhp General Motors 16-258S diesel engines (Serial No. 10836 and 10837), Farrel-Birmingham single reduction gear, two shafts |

| Speed: | 20 knots (37 km/h) |

| Complement: | 65 |

| Armament: |

|

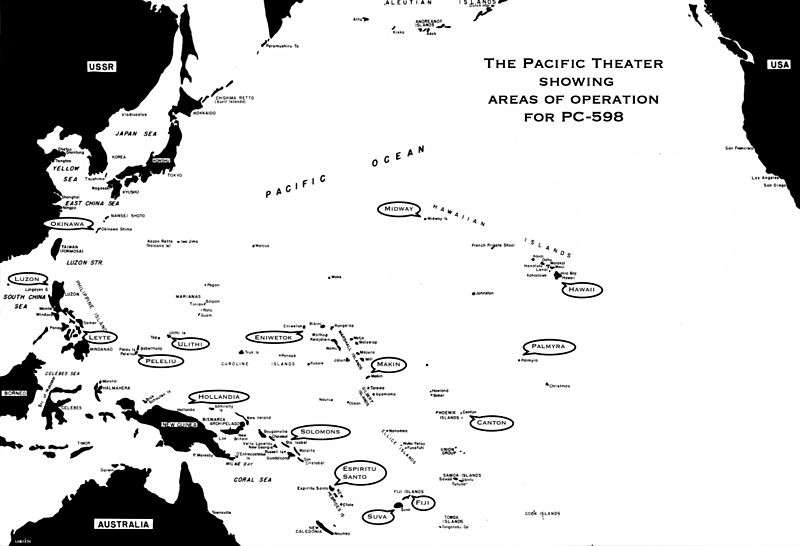

USS PC-598 was a 173' metal hulled PC-461-class submarine chaser that saw duty in the United States Navy in the Pacific Theater during World War II. It was converted to an amphibious landing control vessel during the war and reclassified a Patrol Craft - Control or PCC. It participated in six amphibious invasions as a control vessel.

Commissioning

PC-598 was commissioned in Portland, Oregon on 5 March 1943, Lieutenant Benjamin V. Harrison, Jr. commanding. With her new crew of "plank owners" she left the Commercial Iron Works pier on the Willamette River on 13 March for Astoria and then Seattle, Washington arriving on 15 March. In Seattle, she took on provisions and munitions, and the crew received additional anti-aircraft gunnery training. On 31 March the ship test fired its 3"/50, 40mm and 20mm guns off Marrowstone Point.[1] The ship next relocated to San Diego arriving on 18 April.[2] PC-598 then moved on to San Francisco, arriving 5 May, loaded stores and departed for Pearl Harbor on 9 May.[3]

Hawaii, Midway and Canton

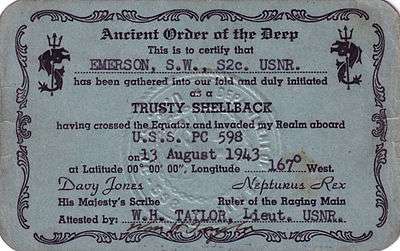

The "subchaser" arrived in Pearl Harbor on 16 May 1943 and spent the next two months towing targets and picket duty on the sonar "ping line" patrolling for enemy submarines near Pearl Harbor. On 7 August the ship sailed to Palmyra Atoll and Canton Island. The equator was crossed at 167 degrees West on 13 August and the new "polliwogs" were initiated by the experienced "shellbacks" among the crew into the Ancient Order of the Deep.[4]

The crew enjoyed the beach at Canton and returned to Pearl Harbor on 25 August. The following day Lieutenant Harrison was relieved of command and Lieutenant William H. Taylor assumed command of the ship.[5]

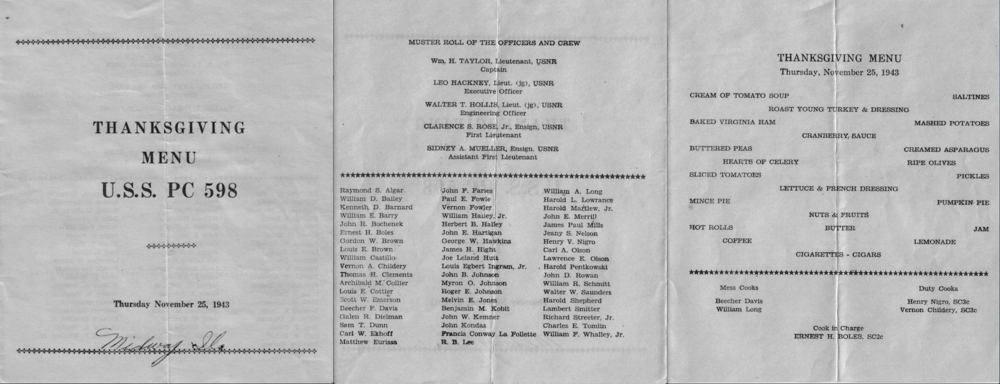

September, October and November 1943 were spent patrolling and escorting ships between Midway and Pearl Harbor, including the fleet oiler Neshanic and the transport William Ward Burrows. Thanksgiving 1943 was spent at Midway.

Back at Pearl Harbor the ship was docked for an engine overhaul on 9 December which was completed on 21 December in preparation for heading towards harms way in the Western Pacific.

Makin, Espiritu Santo and Fiji

On 31 January 1944 the ship was underway from Pearl Harbor to Espiritu Santo, escorting the cargo ship Vega and the Liberty ship Mary Bickerdyke.[6] First stop was Makin Atoll in the Gilbert Islands on 9 February. At Makin were Hydrographer, there to survey the lagoon and anchorages, and the destroyer Capps, late of Scapa Flow, Scotland and Gibraltar in the Atlantic. Departing the atoll on 13 February, the ship stopped briefly at Funafuti on 16 February, anchoring alongside the repair ship Luzon and taking fuel and water from the minesweeper, YMS-290. The ship departed Funafuti on 16 February, detouring to collect the tanker Gulfbird and escort it to Espiritu Santo, entering Selwyn Straight in the New Hebrides on 20 February.[7] That same day, unable to raise anchor, 45 fathoms of chain and the anchor were cut loose and marked with a buoy to be recovered later by the tug Rail, a Pearl Harbor survivor.[8] On 27 February the ship was degaussed at Espiritu Santo to reduce the risk of detonating magnetic mines.[9]

Dull, monotonous duty in dismal surroundings

Force 7 winds and rough seas removed the upper racks mousetrap and capstan control on 4 March. PC-598 spent 7–9 March hunting for a reported enemy submarine with the destroyer Coolbaugh, later determined to be a wild goose chase. The storm damage to the capstan was finally repaired 25 March. The same day the crew test fired their 20mm Oerlikon guns at a towed sleeve in company with SC-502 and SC-639, finding the new Mark 14 sights produced poor results compared to the previous method involving the use of tracers. During March, the sub chaser escorted an odd assortment of ships to and from collection and dispersal points near Espritu Santo, including the transports Naos and Lyra, a US Army cargo vessel F-53, the tanker Cape Hatteras, the cargo vessel Tjibesar and a Dutch merchant ship Boschfontein. On 26 March the ship headed for Suva, Fiji with two Liberty ships, Ethan A. Hitchcock and Edwin Meredith. Edwin Meredith peeled off on its own on 29 March, but Ethan A. Hitchcock continued on with the sub chaser to Suva, arriving 30 March. PC-598 then proceeded solo to Vunda Point at Viti Levu Island.[10]

The PC returned from the Fiji Islands to Espritu Santo on 3 April, in company with the tanker Egg Harbor. April was spent operating in the area of Espiritu Santo, principally on escort duty in the company of other tankers including Soledad, Pequot Hill, Crater Lake, Sparrow's Point, Stanvac Capetown and Charlestown. The sole exception was time spent with the ammunition ship Mauna Loa, escorted 27–28 April. Captain Taylor referred to this period in the ship's War Diary as dull, monotonous duty in dismal surroundings in areas remote from any likelihood of meeting enemy action.[11]

The ship was able to briefly hone its ASW (anti-submarine warfare) skills on 7 April, practicing on a live submarine, S-31, a World War I era submarine returned to active service. The submarine also played a leading role in the 1933 MGM movie Hell Below.[12]

While at Espiritu Santo, PC-598 continued training exercises, working again with S-31 on 1 and 2 May, anti-aircraft practice with the sub chaser SC-1327 on 5 May and attack and recognition classes for the crew on 8 May. Beginning 9 May, PC-598 spent 4 days patrolling the Wawa Channel and then began a routine overhaul alongside Oceanus that lasted until 19 May, during which the pesky Mark 4 sights were removed.[13]

Cruising with the Free French Navy

On 22 May the ship left for Guadalcanal escorting a convoy under the command of Savorgnan de Brazza, a Free French ship which had sunk a Vichy sister ship of the same class in the Battle of Gabon in 1940 and rescued 76 survivors of the British ship Clan Macarthur, sunk in 1943 by a German submarine east of Madagascar.[14] The convoy included the tanker Cape Pillar, the Liberty ship Richard Moczkowski and the U.S. Army transport William R. Gibson. The convoy arrived safely at Guadalcanal on 25 May and PC-598 returned to Espiritu Santo to collect another.[15]

Marine airmen rescued at sea

On 30 May things got a bit more exciting for the ship. While escorting Kalita from Espiritu Santo to Guadalcanal, PC-598 rescued two USMC airmen from a downed Gruman TBF-1 Avenger out of Turtle Bay Field, Espiritu Santo. The plane, part of Marine Torpedo Bombing Squadron 232 (VMTB-232),[16] was on a routine flight but got lost in bad weather, ran low on gasoline and its crew decided to ditch the plane near the convoy. The rescued crewmen were 1st Lieutenant A. J. Aune and Sargent L. J. Eickhoff.[17]

The convoy arrived safely on 1 June and the ship spent the next five days moored in Tulagi Harbor at Florida Island near Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. For the remainder of June 1944, PC-598 patrolled off Guadalcanal and escorted ships, including the Victory ship Canada Victory, later sunk by a kamikaze at Okinawa in April 1945,[18] the Liberty ship Paul Revere, the cargo vessel Arided and Norwegian freighter Narvik.[19] On 22 June Lieutenant (jg) Leo Hackney took command of the ship and Lieutenant Taylor was transferred to the Submarine Chaser Training Center in Miami.[20]

Conversion to Patrol Craft - Control (PCC)

The ship returned to Espiritu Santo on 4 July, screening a convoy. For the rest of July the ship remained moored at Espiritu Santo and the crew received gunnery, recognition and firefighting training at the island’s "Coconut College". Although not officially reclassified as such until after the end of the war,[21] it was here the ship was modified to accommodate its new role as a Patrol Craft - Control (PCC).[22] Thirty-five PCs were converted to Patrol Craft - Control (PCC) for use in amphibious landing operations. Extra personnel (eight radiomen, two signalmen, one quartermaster and two communications officers), accommodations and communications equipment were added, the weight compensated for by removal of other equipment. Near the end of the war, twin-mount 20 mm guns replaced the single mount 20s.[23] In addition, the PCCs were fitted with improved SU radar.[24] PCs proved exceptionally adapt as Control Vessels, guiding waves of landing craft during numerous amphibious landings in the European and Pacific Theaters. In the Pacific, the PCCs were assigned to the Seventh Fleet and participated in all of MacArthur's island-hopping.[25]

The Solomon Islands

On 4 August 1944 PC-598 left Espiritu Santo for Guadalcanal escorting the cargo ship Antares, arriving 6 August. The ship moored at various locations including Tulagi Harbor, Port Purvis, Gavona Inlet, McFarland Point and the Russell Islands over the next 12 days.[26]

Death of a shipmate

On 17 August the ship was anchored in Anonyma Cove at the Russell Islands when SM3c Galen R. Dielman was fatally wounded by gun fire from the beach off Pavuvu, which was being used as a staging area for the 1st Marine Division.[27] It was later determined the sailor was killed by a bullet fired from a Marine rifle range on the island. Last rites were held in honor of Dielman aboard ship by Navy Chaplain Lieutenant Davis from the amphibious force command ship Mount McKinley. Dielman was buried ashore.[28]

From 18 to 25 August the ship ran between the Russell Islands and Florida Island. Between 26 and 29 August PC-598 was involved in practice landings as a control ship off Cape Esperance, Guadalcanal in preparation for the upcoming invasion of Peleliu. Among the ships involved in the exercise was SC-669, the only SC class subchaser to receive credit for sinking an enemy submarine, I-178.[29] The end of August saw PC-598 moored at Purvis Bay, Florida Islands.[30]

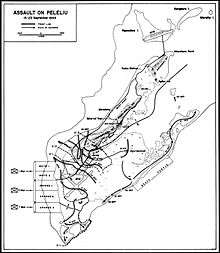

Invasion of Peleliu (Operation Stalemate II)

On 4 September 1944 PC-598 formed up with the Tractor Group of the Western Attack Force and began anti-submarine screening on the way to Peleliu. The convoy arrived at Peleliu in the early morning of 15 September. The invasion plan called for the 1st Marine Division to assault the beachhead with three regiments. The 1st Marine Regiment (under the command of Colonel "Chesty" Puller) would be on the left flank, assaulting beaches White 1 and White 2. In the center would be the 5th Marine Regiment assaulting beaches Orange 1 and Orange 2. The right flank would be held by the 7th Marine Regiment assaulting Orange 3.[31]

At 0630 the Beachmaster and Communications team, Marine observers and newspaper correspondents arrived aboard. Acting as a guide ship for White Beach 2, the ship advanced from the line of departure and moved toward the beach. They bombarded the shore with 46 rounds from their 3″/50 caliber gun, then advanced to the transfer line. The PC remained there as control ship for the LCIs and LVTs of the 1st Marine Division en route to the beachhead. At 0905 the ship assumed guide ship duties for the entire White Beach landing area and remained there overnight.[32]

Burial at sea

The following day, 16 September, the ship was relieved of control duty. The Beachmaster and Communications team left the ship which was then assigned to the anti-submarine screen for the LST Tractor Group at Peleliu until 25 September.[33] While on the screen on 19 September, the ship stopped to identify a floating corpse, which was determined to be that of an American Marine. A thorough search of body revealed no identification whatsoever, the body being in such a state that no fingerprints were possible. The crew weighted and sank the body with a length of anchor chain in accordance with instructions from the destroyer Hazelwood.[34]

Late in the day on 26 September, the LST Tractor Group formed in cruising disposition and proceeded to New Guinea. The Tractor Group arrived at Hollandia, New Guinea on 30 September and anchored in Humboldt Bay.[35]

Aftermath

The Battle of Peleliu remains controversial due to the island's lack of strategic value and a casualty rate which exceeded all other amphibious operations during the Pacific War. The 1st Marine Division was severely mauled and remained out of action until the invasion of Okinawa. On Peleliu, the 1st Marine Division suffered over 6,500 casualties, over a third of the division. The 81st Infantry Division suffered nearly 1,400 casualties while on the island.[36] The Japanese defenders, consisting of an estimated 10,500 men, were annihilated,[37] but would have lacked the means to interfere with US operations in the Pacific if the island had been by-passed, as had many other Japanese garrisons.[38] Although deemed an essential stepping stone to the Philippines at the time, Peleliu never played a key role in subsequent US operations,[39] but did show Americans the pattern of future Japanese island defense and provided experience in assaulting heavily fortified positions such as they would find again at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.[40]

Hollandia, New Guinea

October 1944 was a busy month for the ship. She began the month moored in the great anchorage of Humboldt Bay, the staging base for Leyte Island in the Philippines, the next invasion. Between 1 and 10 October she replenished her fuel and water and effected repairs to the ship. She was often moored alongside sister control vessels, including PC-623, PC-1119 and PC-1129.[41] In late October 1944, both PC-623 and PC-1119 would participate in the rescue of 1150 survivors of Task Unit 77.4.3 ("Taffy 3") from the carrier Gambier Bay and the destroyers Samuel B. Roberts and Hoel, lost during the Battle off Samar Island.[42] PC-1129 was sunk 31 January 1945 during Operation Mike VI by a Japanese Shinyo "suicide boat" off Nasugbu, while serving as flagship for the control unit, TU 78.2.7.[43][44]

11 October found PC-598 at Pier #1 in Hollandia. Corporal Howard F. Klawitter, U.S. Army Photographer reported aboard for temporary duty assigned by the Sixth Army to accompany the ship and photograph the Leyte landings. On the same day, the wooden hulled subchaser, SC-648 was moored to starboard side. Theodore R. Treadwell, author of Splinter Fleet: The Wooden Subchasers of World War II, served aboard SC-648 for two years, including nine months as commanding officer.[45]

On 12 October PC-598 took part in training exercises as a landing control ship in preparation for the Leyte Island landings. The ship moored later that day in Hollandia Bay outboard of Murzim, a cargo ship used as an ammunition station ship. Manned by a United States Coast Guard crew, Murzim is the only US Navy ship in wartime whose crew was ordered to "abandon ship" while dockside. Alex Haley, author of Roots: The Saga of an America Family, served aboard her during the war.[46]

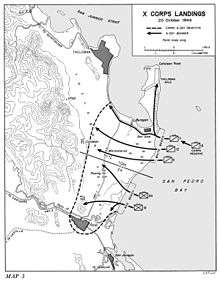

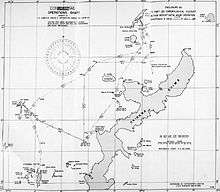

Invasion of Leyte (Operation King II)

The next day, 13 October 1944, PC-598 took on fuel and lube oil and proceeded to form up with Task Force 78.1, the Palo Attack Group of the Northern Attack Force headed for Leyte.[47] PC-598 took position 300 yards behind PC-623 in the control ship column. On 17 October, the ship relieved the Royal Australian Navy destroyers Arunta, responsible for sinking Japanese submarine RO-33 in August 1942,[48] and Warrarunga as each refueled, and then returned to her position in the convoy.[49]

The Northern Attack Force, which was delivering the 1st Cavalry Division and the 24th Infantry Division of the 6th Army's X Corp, took a week to arrive at Leyte Gulf. PC-598 entered San Pedro Bay with the Northern Attack Force at 0740 on 20 October. By 0820 she closed with the attack transport Dupage to collect Lieut. E.E. Boelhauf, who was later also a Beach Control Officer at Okinawa,[50] and his communication party. She proceeded to her assigned station on Red Beach and anchored at 0902. The first wave steamed by at 0943. After the last wave passed at 1128, the Beach Control Officer and communications team left the ship.[51]

MacArthur returns to the Philippines

At 1330 the landing area was secure enough for General Douglas MacArthur to stride from a landing craft through knee deep surf onto Red Beach, keeping his promise to return to the Philippines.[52] By mid-afternoon, PC-598 repositioned closer to the landing area and waited for orders from Blue Ridge, the amphibious landing command ship for the Northern Attack Force. By 1815 they left their position at Red Beach under orders to report to the Commander of LCI Flotilla 7 and provide screening for the transport area.[53]

Two days later, on the morning of 23 October, while maneuvering to go alongside tank landing ship LST-465, the subchaser hit a reef that was "improperly charted and buoyed". The stern of the ship grounded in the gravel of the reef. By noon, with assistance from the tug Quapaw, the ship was floated off the reef.[54] Inspection showed only slight damage to screws. The PC refueled and took on water from LST-465. By 1600 they were underway with the patrol frigate Carson City and PC-1129 to rendezvous with LST Flotilla 23 and provide an escort back to Hollandia.[55]

Aftermath

In all 132,000 troops were landed on Leyte. Fearing that the loss of the Philippines would result in the loss of shipping lanes to their oil supplies in South East Asia, the Japanese committed the remnants of the Imperial Japanese Navy in what would become the greatest naval battle in history, the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Between 23 and 26 October 1944, there were four separate engagements: the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea, the Battle of Surigao Strait, the Battle of Cape Engaño and the Battle off Samar, as well as other actions.[56] In four days of fighting the Japanese lost 26 of their finest ships: three battleships, one large carrier, three light carriers, six heavy cruisers, four light cruisers and nine destroyers, ending Japan's dream of being a naval power.[57]

Return to Hollandia, New Guinea

Convoy attacked by submarine

Near midnight on 24 October 1944, the convoy was in the Philippine Sea east of Mindanao. Two explosions were heard and PC-598 went to General Quarters. LST-695 had been torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-56.[58] 20 hours later and 175 miles to the north-east, I-56 would torpedo the carrier Santee during the Battle of Leyte Gulf.[59] I-56 was eventually sunk by five destroyers and aircraft from the carrier Bataan east of Okinawa on 18 April 1945.[60]

LST-986 commenced to tow the disabled LST-695.[61] Together with LST-170 they formed an independent LST Group and were escorted by PC-598 to Peleliu, arriving on 27 October, where the injured were hospitalized.[62] Leaving with the two undamaged LSTs, PC-598 returned to Hollandia and arrived at Humboldt Bay on 30 October, mooring alongside the Destroyer Repair Base Dock. Corporal Klawitter was detached from his temporary duty aboard PC-598 on 31 October. He died later in the war from wounds sustained in combat.[63]

Dry dock repairs and recovery

The first four days of November were spent in the floating dry dock AFD-24 for repairs to the ship, most likely the damage caused by running aground at Leyte on 23 October. With its propellers and shafts removed to allow repairs, on 5 November the ship was towed from dry dock to the Destroyer Repair Base Dock at Hollandia. There she was moored starboard side to SC-744, which would be sunk within a month by a kamikaze at Leyte Gulf.[64] Eleven days later, on 16 November, the PC returned under tow by LCMs to AFD-24 for dry docking and underwater repairs which were completed around midnight. The next day, the ship left dry dock and returned under its own power to the Destroyer Repair Base dock where it remained though the end of November. Lieutenant (jg) Clarence S. Rose Jr., the ship's Executive Officer, was ordered to take command on 19 November. Lieutenant Hackney, was detached from duty as Commanding Officer and left the ship.[65]

During the first three weeks of December, the ship lay anchored in Humboldt Bay or moored along Liberty dock #1 in Hollandia. 18 December was spent at the firing range, holding anti-aircraft practice and running the degaussing range. The ship received replacement crew members and replenished supplies, water and fuel. Late on 22 December they left Hollandia to proceed to Aitape, New Guinea under orders to join the Seventh Amphibious Force, which was forming for the invasion of Lingayen Gulf, Luzon in the Philippines.[66]

Exercises off Aitape

PC-598 arrived at Aitape the next day and anchored in Ataipe Road. On the day before Christmas 1944, Captain Stephen G. Barchet, former commanding officer of the submarine Argonaut, reported aboard to assume the duties of Senior Control Officer for White Beach at the Lingayen Gulf landings. Captain Barchet served as Operations Officer for the 7th Amphibious Force in the Pacific. In this assignment he coordinated planning and supervised operations of approximately 1,000 ships, consisting of cruisers, destroyers, transports and landing craft. These operations included the assault landings at Lingayen Gulf.[67]

On the day after Christmas, Lieutenant William H. Moore, USNR reported aboard for temporary additional duty with a six man communications team to participate in the landing rehearsal at Aitape, scheduled for 27 December. On board to watch the exercise was Brigadier General Alexander N. Stark, Jr.,[68] Deputy Commander of the 43rd Infantry Division which would make the White Beach landing at San Fabian in the Lingayen Gulf on 9 January 1945.[69]

En route to Luzon

The landing exercise completed, PC-598 was underway the next day, 28 December, as part of the anti-submarine screen for the Luzon Attacking Force from Aitepe, New Guinea. While en route, on 31 December, the ship delivered mail from Blue Ridge to ships in the convoy, including tank landing ship LST-466, the attack transports Cavalier, DuPage, Fayette, and Fuller, cargo ships Auriga, Indus, and Aquarius and the destroyer Braine. On 22 May 1945, while on picket duty near Okinawa, Braine was struck by two kamikazes. Eight officers and 59 enlisted men were killed. 102 others were wounded, 50 seriously enough to be hospitalized. Braine suffered the highest casualty rate of the war for any destroyer that was not actually sunk.[70]

Naval mine sighted and sunk

New Year's Day 1945 saw PC-598 screening for the San Fabian Attack Force. At 1756, they sighted a floating mine about 1000 yards off the port bow. The ship maneuvered to the vicinity of the mine and waited for the convoy to pass. Firing both 20mm rounds and .30 caliber rifle bullets, the mine was sunk. It was a spherical type, judged to weigh 450 pounds and believed to be an enemy mine, as the horns were 10 to 12 inches long.[71]

Last surface ship engagement of World War II

The San Fabian Attack Force continued on to the Lingayen Gulf during the first week of 1945. PC-598 screened the convoy and periodically delivered mail among the ships, including officers mail on 6 January to the attack transports Fayette, Freemont and DuPage, which was struck by a kamikaze four days later, killing 35 and wounding 103.[72] On 7 January PC-598 refueled and took on water from the fleet oiler Pecos, a more fortunate ship. That night, at 2245, destroyers from the starboard side of the anti-submarine screen were observed firing at a surface target about 11 miles away.[73] Destroyers Ausburne, Braine, Russell, and Shaw were sinking the Japanese destroyer Hinoki,[74] lost with all hands while attempting to escape from Manilla Bay.[75] This proved to be the last engagement between surface ships of World War II.[76]

Invasion of Lingayen Gulf (Operation Musketeer Mike I)

Flagship for Commander Task Unit 78.1.7

On 9 January 1945 the San Fabian Attack Force entered Lingayen Gulf at 0345. Released from anti-submarine duties at 0630, PC-598 assumed the duties of Senior Control Vessel, acting as Flagship for CTU 78.1.7 at its assigned position on the line of departure for White Beaches, 4,000 yards off shore. Naval and Army officers and their staffs came aboard to use the ship as an observation and control center. Landing operations were controlled by Captain Barchet, who had been on board the ship since New Guinea.

The first wave of the 43rd Infantry Division was dispatched towards the beach at 0902. By 1840 the PC was anchored 2000 yards off shore near White Beach 2. The ship's crew sighted three enemy aircraft and fired at one plane which escaped flying very high.[77]

PC-598 remained anchored near the White Beaches, occasionally maneuvering to support operations. Near midnight on 11 January the ship came under fire from beach installations with shrapnel falling nearby from shell bursts in the air. The enemy guns were silenced within minutes by counter fire from destroyers in the Gulf.[78] Captain Barchet and his control communications team left the ship on 15 January, replaced by Lieutenant Commander J.B. Avery who had been assisting Barchet since 14 January. The ship continued as flagship for Commander Task Unit 78.1.7 and later 78.1.11 until 28 January. On 29 January the ship was relieved of its duties and reported alongside the landing craft repair ship Amycus for minor repairs, which were completed by the morning of 31 January. That evening PC-598 reported for duty as a screen vessel for a convoy departing from the Lingayen Gulf to Leyte.[79]

Aftermath

Over 200,000 soldiers were landed in the Lingayen Gulf during this period. American naval forces suffered relatively heavy losses, particularly to their convoys, due to kamikaze attacks. During the first two weeks in January, a total of 24 ships were sunk and another 67 were damaged by kamikazes including the battleships Mississippi, New Mexico and Colorado, the Australian heavy cruiser Australia, the light cruiser Columbia, and the destroyers Long and Hovey. Following the landings, the Lingayen Gulf became a vast supply depot to support the Battle of Luzon.[80]

Return to the Solomons

The convoy from Lingayen Gulf arrived in San Pedro Bay, near Leyte, on 2 February 1945 where Captain Rose reported to CTF 78 on Blue Ridge. The ship took on stores, fuel and water and anchored for the night off Samar Island. The next day the convoy left at 1800 to Guadalcanal via the Admiralty Islands. On 14 February PC-598 passed the entrance nets to Seeadler Harbor at Manus in the Admiralty Islands[81] where three months earlier the ammunition ship Mount Hood exploded, killing all aboard her, obliterating the ship and sinking or severely damaging 22 other nearby ships.[82]

_explodes_at_Seeadler_Harbor_on_10_November_1944.jpg)

Once more the ship's fuel, water and supplies were replenished. PC-598 was underway again in the company of other patrol craft on 16 February and arrived off Lunga Point, Guadalcanal on 20 February. At Guadalcanal, Communications team #55 commanded by Lieutenant (jg) P.W. Cochran reported aboard for temporary duty and the ship was ordered by CinCPac to report as a control vessel to ComPhib Group 4. On 21 February the ship visited the Florida Islands, anchored in Govana Inlet and later made its way to the Egan Bluff water hole at Port Purvis to take on water.[83]

PC-598 spent the last eight days of February anchored at various locations at Purvis Bay, Florida Islands in "nests of ships" including the tank landing ships LST-220, later used as a target vessel for atomic bomb test "Able" during Operation Crossroads in the summer of 1946,[84] LST 213, involved in the rescue of survivors after the sinking of Gambier Bay during the Battle off Samar and LST-698, the subject of the book LSTs, the Ships with the BIG MOUTH and what made these ships so essential in island actions of World War II (1944-45) written by a crew member, Homer Haswell. PC-598 spent six of these days alongside the repair ship Briareus undergoing voyage repairs and installing new control equipment.[85]

Tractor Group Baker to the Ryukyus

The first six days of March, PC-598 participated in training exercises off Cape Esperance, Guadalcanal in preparation for the landings in Okinawa. The ship then retired to Govana Inlet, Florida Islands for repairs provided by AFD-14. Late in the evening of 9 March, the ship joined Tractor Group Baker en route to the Russell Islands, arriving 11 March at Macquitti Bay. By 18 March Tractor Group Baker was once again on the move, this time to Ulithi in the Western Carolina Islands.[86]

.jpg)

On 21 March, the sub chaser passed into Ulithi Harbor via Mugai Channel and anchored in the northern anchorage. While at Ulithi, the ship replenished stores from the non-self propelled storage barge, IX-151 and took water from the new distilling ship, Abatan, which provided potable water to landing craft, patrol vessels and escort ships unable to produce their own water.[87] Like many smaller ships, PCs could not produce their own fresh water and were reliant on larger vessels for drinking water.[88]

Just before noon on 25 March, Lieutenant Vrooman, Blue Beach Control Officer, came aboard for the last leg of the journey to Okinawa. The submarine chaser then joined the anti-submarine screen for Tractor Group Baker, en route from Ulithi to the Ryukyus. The Tractor Group arrived at the Ryukyus on 31 March.[89] Late that afternoon, PC-598 pulled alongside LST-834 refueled and replenished water. LST-834 is the central figure in Waddling to War by Bob Shannon.

At 1728, as PC-598 began the transition from anti-submarine screening to control vessel duties, the crew dropped eight Mousetraps (ASW Mark 20 anti-submarine rockets) and their fuzes overboard.[90]

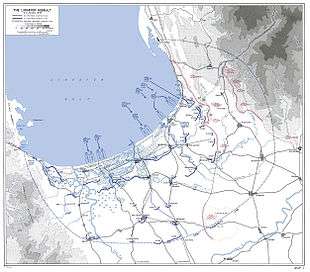

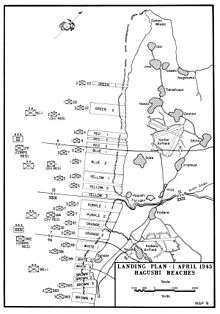

Invasion of Okinawa (Operation Iceberg)

1 April 1945 was both Easter Sunday and April Fool's Day, a coincidence not unremarked on by the crew of PC-598. It also marked the start of Operation Iceberg, the invasion of Okinawa. Released from screening duty at 0405, PC-598 proceeded to the line of departure at Blue Beach to serve as the Control Vessel. While approaching the line, several Japanese dive bombers, Aichi D3A "VALS", were seen attacking the ships. One VAL approaching from the beach came within range of the ship's guns and the sub chaser opened fire. Hits were observed and the plane caught fire and crashed into the sea.[91]

PC-598 anchored at its assigned station with Lt. Vrooman acting as Blue Beach Control Officer. Various Naval and Marine officers came aboard to use the ship as a control center during the landing phase of the operation. The first assault wave was dispatched at 0800.[92] The 7th Marine Regiment (1st Marine Division) was assigned to Blue Beaches 1 and 2, and landed with its 1st and 2nd Battalions abreast followed by the 3rd Battalion.[93] By early afternoon, the ship maneuvered 1000 yards closer to Blue Beach and anchored for the night. The ship continued to act as Blue Beach Control Vessel until 5 April when it was detached and reassigned as Purple Beach Control Vessel in early afternoon.

Kamikaze onslaught begins

The Japanese kamikaze onslaught against U.S. ships off Okinawa begins in earnest on 6 April. The ship, anchored and serving as Purple Beach Control Vessel, along with the rest of the fleet, is under attack from numerous airplanes. The ship’s guns fire on two VALS in range, downing one into the sea.[94]

Suicide attacks by planes at Okinawa sank 26 U.S. war and merchant ships and damaged 225 others.[95] On 6 April alone, six ships were sunk at Okinawa including the destroyers Bush and Colhoun, the minesweeper Emmons, and the cargo ships Hobbs Victory and Logan Victory.[96] Many more were damaged. In the midst of this inferno, PC-598 is forced to maneuver to avoid a flaming gasoline barge drifting in the direction of the ship.[97] Kamikaze attacks continued throughout the remainder of the war expending 1,900 Japanese planes and pilots.[98]

Control Vessel for TransRon 16

Except for a one-day excursion on 24 April to Kerama Retto,[99] a protected anchorage to the west, PC-598 remained anchored off the Hagushi landing beaches on the west coast of Okinawa through most of April, serving as Control Vessel for the unloading of Transportation Squadron 16. On 9 April, Lieutenant Commander Dawes, USNR came aboard as Control Officer at Purple Beach to supervise the unloading. Relieved of control duty on 11 April, the ship proceeded to Coronis for repairs which were completed 14 April after which the ship returned to its control duties. On 18 April Commander Quine, USN came aboard as Control Officer. During April, nightly attacks were made by enemy aircraft on the ships lying at anchor off the Hagushi landing areas. On each occasion the Control Vessel concealed itself in smoke and withheld fire.[100]

Nago Bay

The ship was relieved of its Control Vessel assignment on 30 April and ordered to Nago Wan (Nago Bay), Okinawa.[101] While at Nago Wan on 2 May, Lieutenant (jg) Rose was relieved of command of the ship and replaced by Lieutenant (jg) Raymond C. Chaisson, USNR, previously the Executive Officer.[102]

On 5 May PC 598 was moored port side to the landing craft support ship LCS-62 in order to take on water. After the initial landing bombardment, LCS-62 had been assigned to picket ship duty on stations 25–80 miles off the main invasion beaches of Okinawa to intercept Japanese planes and to warn the main forces of the approach of enemy aircraft. Typical of many of the radar picket ships, LCS-62 survived over 150 air raids and went to general quarters over 200 times before the campaign ended.[103]

Mail and taxi service

On 9 May the submarine chaser was ordered to Ie Shima where she took on the less glamorous role of delivering mail and passengers. Ie Shima, a small island twenty miles north of the Hagushi landing beaches, had been captured after a six-day battle on 24 April to provide additional airfields for air strikes in Okinawa and Japan. It is also the final resting place of Ernie Pyle, American journalist and war correspondent, killed there on 18 April 1945.[104]

The sub chaser ran a daily route starting from the amphibious force command ship Panamint at Ie Shima to the dock landing ship Epping Forest at Nago Wan to the amphibious force command ship Eldorado at Bisa-Gawa, off the original Hagushi landing areas, and back to Ie Shima.[105] On 14 May while at Ie Shima, PC-598 received water from the tank landing ship LST-808. While still at Ie Shima four days later, LST-808 was struck by a Japanese aerial torpedo. Pushed onto a nearby coral reef by U.S. ships, she was attacked a second time on 20 May by a Japanese kamikaze.[106]

On 17 May PC-598 was relieved as mail ship by SC-1278 and returned to Nago Wan. While there, the ship continued to make regular trips to Hagushi to take on water and deliver mail and passengers to various ships, including the amphibious force command ship Ancon on 21 May. In need of repairs, the ship relocated to the Hagushi anchorage and moored alongside Coronis on 23 May, remaining until repairs were completed on 30 May.[107]

During May air attacks remained a daily threat to the U.S. fleet at Okinawa, including four major kamikaze attacks involving 550 Japanese planes.[108]

Iheya and Aguni operations

Iheya Shima and Aguni Shima are two small islands about 30 miles north and west, respectively, of Okinawa. Because of the heavy damage sustained by the U.S. fleet and especially the radar pickets during kamikaze raids, the decision was made to capture them for long-range radar and fighter director facilities.[109] On 3 June, PC-598 accompanied the amphibious landing force to Iheya Shima, providing anti-submarine screening en route to the island and during the landing. The Aguni Shima landing followed on 9 June, with PC-598 providing similar services.[110] Both landings were unopposed.[111]

After Aguni Shima, PC-598 remained in and around Hagushi anchorage including one excursion on 16 June to pick up passengers arriving at seaplane anchorage V-4 at Kerama Retto and deliver them to Hagushi. On 23 June the PC was ordered to escort the cargo ship San Bruno to Nakagusuku Wan.[112] This large bay on the southern coast of Okinawa was referred to as Buckner Bay by American soldiers in honor of General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr., commander of the 10th Army, killed on Okinawa 18 June 1945.[113] Buckner was the highest-ranking U.S. military officer lost to enemy fire during World War II.[114]

Aftermath

The invasion of Okinawa was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific Theater.[115] About 548,000 men of the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps took part, with 318 combatant and 1139 auxiliary vessels.[116] The toll on US ground troops exceeded 12,500 killed, 36,600 wounded and over 26,000 neuropsychiatric “non-battle” casualties. These were the highest experienced in any campaign against the Japanese. The Navy suffered over 4,900 dead and 4,800 wounded, the most in any single operation. The US also lost 36 ships and another 368 damaged, mostly by air attack. 763 carrier based aircraft were lost to all causes.[117] At least 110,000 Japanese troops and native islander defenders were killed and only 7,400 taken prisoner during the battle.[118] At least 42,000 civilians on the island also died during the battle, caught between the opposing forces.[119]

These casualty figures, as well as those from other island campaigns, were used by U.S. military planners to estimate that Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands, would result in well over 1,000,000 U.S. and 5,000,000 Japanese casualties. These estimates put the decision made to use atomic weapons against the Japanese in context.[120]

Goodbye to all that

The next morning in Hagushi anchorage, PC-598 received lube oil, fuel and fresh water from the tanker Armadillo and collected guard mail from PCS-1390. By 1030 on 24 June 1945 the ship was en route from Okinawa to Pearl Harbor via Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshall Islands.[121] The convoy took 11 days to travel the 2,145 nautical miles between Okinawa and Eniwetok Atoll, arriving on 5 July.[122] After the war, this remote atoll was used for nuclear testing as part of the Pacific Proving Grounds. Forty-three nuclear tests were fired at Eniwetok from 1948 to 1958, including Ivy Mike, the first full scale test of a thermonuclear device.[123]

The convoy of LSTs left the atoll, escorted by PC-598, 3 days later on 8 July. This last leg of the trip to Pearl Harbor was another 2,000 nautical miles. The journey went smoothly until 12 July when PCS-1379 developed engine trouble and was taken under tow by PC-598 and other ships in the convoy. PC-598 arrived safely at Pearl Harbor at noon 21 July 1945.[124] It had left Pearl Harbor 537 days earlier on 31 January 1944.

The war was over for PC-598 and its crew, but no one knew it at the time. The U.S. Navy and Army were preparing for the invasion of the Japanese home islands and wanted all available ships in good repair. In late July, the war weary ship was sent for a major overhaul of its engines. It unloaded its munitions, discharged its fuel at Merry Point and berthed at Baker #8 at the Navy Yard in Pearl Harbor.[125] On 16 August Lieutenant (jg) Chaisson was relieved of duties as Commanding Officer, replaced by Lieutenant (jg) Edwin J. Adams, Jr. the Executive Officer.[126]

To the enormous relief of U.S. military personnel in the Pacific, the war ended 14 August 1945 after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[127][128] The engine overhaul was eventually completed and the ship returned to Astoria, Oregon just before Christmas Day, 1945. Like many of the hundreds of smaller vessels built during the war, PC-598 was quickly decommissioned. On 16 November 1946 the ship was sold to the Foss Tug and Barge Company of Tacoma, Washington.[129][130]

A China connection?

Between 1946 and 1949, 14 ex-PCs were reportedly transferred to the Kuomintang government of China (Nationalist forces) including ex-PCs 490, 492, 593, 595, 598, 1088, 1089, 1090, 1091, 1233, 1247, 1549, 1551, and 1557.[131] When the Nationalist forces fled the mainland for Taiwan in January 1949, ten of the ex-PCs went with them, including ex-PCs 490, 492, 593, 598, 1089, 1233, 1247, 1549, 1551, and 1557. Four remained on the mainland and served with the navy of the People’s Republic of China (Communist China), including ex-PCs 595, 1088, 1090, and 1091. PC-598 reportedly remained on the naval register the Republic of China (Nationalist China) until 1954.[132][133]

If true, PC-598 was the only ex-PC not transferred directly from the U.S. government to the Kuomintang forces. At least one source admits to some uncertainty regarding a positive identification of PC-598 among these vessels and the fate of the ship remains uncertain.[134]

Awards and honors

PC-598 received four battle stars for her World War II service:[135]

- Western Caroline Islands Operation - Capture and occupation of southern Palau Islands (Peleliu)

- Leyte Operation - Leyte landings

- Luzon Operation - Lingayen Gulf landings[136]

- Okinawa Gunto Operation - Assault and occupation of Okinawa

Depending on time of service, crew members were eligible for one or more of the following medals:

- World War II Victory Medal

- Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with 7 stars

- American Campaign Medal - WWII

- Philippine Liberation Medal with 2 stars

Notes

- ↑ PC-598 Operational Remarks, March 1943

- ↑ PC-598 Administrative Remarks, April 1943

- ↑ PC-598 Administrative Remarks, May 1943

- ↑ "USS PC-598 - Ancient Order of the Deep, 13 August 1943". Wikimedia Commons.

- ↑ PC-598 Administrative Remarks, 26 August 1943

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 31 January 1944

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, February 1944

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, March 1944, p. 4-5

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, February 1944

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, March 1944

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, April 1944

- ↑ "Submarine Photo Archive S-31 (SS-136)". NavSource Naval History, Photographic History of the U.S. Navy.

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, May 1944, p.1

- ↑ "Clan MacArthur". The British and Commonwealth Shipping Company Limited.

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, May 1944, p.2

- ↑ "USN Overseas Aircraft Loss List May 1944". Aviation Archaeological Investigation and Research, AAIR.

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, May 1944, p.2

- ↑ Askew, p. 242

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, June 1944

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, June 1944, p. 2

- ↑ Silverstone, p.186

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, July 1944, p.1

- ↑ Veigele, p. 66-67

- ↑ "PCs converted to PCCs". Patrol Craft Sailor Association.

- ↑ "PC World War II Service". Patrol Craft Sailor Association.

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, August 1944, p.1

- ↑ Sledge, p. 30-33

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 17 August 1944

- ↑ Cressman, p. 162 - "Submarine chaser SC-669 sinks Japanese submarine I-178 30 miles west of Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides, 15°35'S, 166°17'E."

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, August 1944

- ↑ Hough, p. 19

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, September 1944, p. 1

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, September 1944, p. 1

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 19 September 1944

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, September 1944, p. 2

- ↑ Hough, p. 183

- ↑ Garand and Strowbridge, p. 285

- ↑ Chen, C. Peter. "Palau Islands and Ulithi Islands Campaign". World War II Database.

...many historians argue that the overall operation was useless in the grand scheme of the war. The Japanese on this island 'could have been left to wither on the vine without altering the course of the Pacific War in any way', argued William Manchester.

- ↑ Anderson, "Western Pacific", p. 28 "...the minor strategic value of the Palaus left troubling questions about overall American decision making in the Pacific. Intended to support subsequent operations against the Philippines, the airfields and ports of Peleliu and Angaur ultimately proved less than essential."

- ↑ Gypton, Jeremy. "Bloody Peleliu". MilitaryHistoryOnline.

In the end, Peleliu itself provided very little in the way of support for further American operations, although knowledge of and experience against Japanese fukakku tactics were valuable, and would help the Americans deal with similar methods on Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 1–9 October 1944

- ↑ Veigele, p. 210-211

- ↑ Cressman, P. 291

- ↑ "Wreck of USS PC-1129". Wikimapia.

- ↑ "Theodore (Ted) Treadwell Jr.". Splinter Fleet, The Wooden Subchasers of World War II.

- ↑ USS Murzim (AK-95), Wikepedia

- ↑ Bates, p. 696

- ↑ "IJN Submarine R0-33". Imperial Submarines.

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary', October 1944, p. 1

- ↑ Morison, p. 144

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 20 October 1944

- ↑ Anderson, p. 12

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, October 1944, p. 2

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, October 1944, p. 2

- ↑ Bates, p. 23

- ↑ "Battle of Leyte Gulf Facts". World War 2 Facts.

- ↑ Victory at Sea - Episode 16, The Battle for Leyte Gulf

- ↑ Cressman, p. 266, “Japanese submarine I 56 attacks Humboldt Bay, New Guinea-bound TG 78.1 (Commander Theodore C. Linthicum) and torpedoes tank landing ship LST 695 west [sic] of Mindanao, 08°31’N, 128°34’E. LST 986 tows her crippled sister ship to Palau. I 56 survives counterattacks by frigate ‘’Carson City’’ (PF 50).”

- ↑ Cressman, p. 267

- ↑ Cressman, p. 313

- ↑ "Rosenberg, Morton". Rutgers Oral History Archives, (An Interview with Morton M. Rosenberg for the Rutgers Oral History Archives of World War II, Interview conducted by Sandra Stewart Holyoak, Summit New Jersey). Transcript by G. Dorothy Sabatini. June 10, 1999.

So my job as stores watch officer meant that I was responsible for everything on the ship, except water and ammunition, in the way of supplies. So I went into their huge warehouses. ... I saw a huge roll of hawser, ten-inch hawser. It’s rope, so, therefore, it’s the circumference, not the diameter. ... When I brought that back, the captain said, “What are we going to do with that?” I said, “Sir, you never know when we might have to tow somebody.” Do you know a year and a half later, the ship behind us was torpedoed and we were ordered to stand by, and we towed that ship for fourteen hundred miles with the rope I put onboard from the Boston Navy Yard

- ↑ "LST-695". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- ↑ "TEC5 Howard F. Klawitter". National World War II Memorial.

- ↑ Cressman, p. 277

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 19 November 1944

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, December 1944

- ↑ "Rear Admiral Stephen G. Barchet". Fleet Submarine.com.

- ↑ "Stark, Alexander Newton Jr.". The Generals of WWII.

- ↑ MacArthur, et al., p. 254 - 260

- ↑ "Okinawa - "A Fiery Sunday Morning"". USS Braine - DD630.

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, January 1945, p.1

- ↑ "10 January 1945 - Action Report - Lingayen Gulf Operation in San Fabian Area". USS DuPage (APA-41)Official Web Site.

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 7 January 1945

- ↑ Cressman, p. 287

- ↑ "IJN Hinoki: Tabular Record of Movement". Long Lancers.

- ↑ Roscoe, p. 457

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, January 1945, p. 1

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 11 January 1945

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, January 1945, p. 2

- ↑ Invasion of Lingayen Gulf, Wikepedia

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, February 1945

- ↑ "Selected documents relating to the loss of USS Mount Hood". Hyperwar.

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, February 1945

- ↑ "Operation Crossroads: Disposition of Target Vessels". Naval History and Heritage Command.

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, February 1945

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, February 1945

- ↑ "Distilling Ships (AW)". The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Veigele, p. 42

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, February 1945

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, February 1945

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, April 1945, p.1

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, April 1945, p.1

- ↑ Frank, et al., p.113

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, April 1945, p.2

- ↑ Rottman, p. 76

- ↑ Cressman, p. 309-310

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 6 April 1945

- ↑ Rottman, p. 76

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 24 April 1945

- ↑ PC-598 War Diary, April 1945

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 30 April 1945

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 2 May 1945

- ↑ "A Brief History of LCS(L) 62 ". NavSource Naval History, Photographic History of the U.S. Navy.

- ↑ Appleman, et al., p. 163

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, May 1945

- ↑ Cressman, p. 320-321

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, May 1945

- ↑ Appleman, et al., p. 364

- ↑ Frank, p. 5

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, June 1945

- ↑ Frank, p. 5

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, June 1945

- ↑ Frank, p. 353

- ↑ Sarantakes, p. 129

- ↑ Frank, et al., p. 793

- ↑ King, p. 176

- ↑ Appleman, p. 473

- ↑ Appleman, p. 473-474

- ↑ Frank, et al., p. 396

- ↑ Hansen, “...because the Japanese on Okinawa... were so fierce in their defense (even when cut off, and without supplies), and because casualties were so appalling, many American strategists looked for an alternative means to subdue mainland Japan, other than a direct invasion. This means presented itself, with the advent of atomic bombs, which worked admirably in convincing the Japanese to sue for peace [unconditionally], without American casualties."

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 24 June 1945

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 5 July 1945

- ↑ Diehl, Sarah and Moltz, James Clay. Nuclear Weapons and Nonproliferation: A Reference Book. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO, 2002, p. 208.

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, July 1945

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 23 July 1945

- ↑ PC-598 Log Book, 16 August 1945

- ↑ Appleman, et al., p. 474, "...there came the almost unbelievable and joyous news that the war was over. "

- ↑ Sledge, p. 312, "We received the news with quiet disbelief coupled with an indescribable sense of relief."

- ↑ "Submarine Chaser Photo Archive, PCC-598, ex-PC-598". NavSource Naval History, Photographic History of the U.S. Navy.

- ↑ Silverstone, p. 186

- ↑ "People's Liberation Army Navy (People's Republic of China), Escorts, Chien Feng submarine chasers (1942-1945/1946-1949)". Navypedia.

- ↑ Gardiner, p. 57

- ↑ Blackman, p. 173 (1951-52), p. 148 (1952-53), and p. 154 (1953-54)

- ↑ Gardiner, p. 57

- ↑ Navy and Marine Corps Awards Manual, p. 117

- ↑ Navy and Marine Corps Awards Manual, as amended by memo dated 19 August 1954, Enclosure 7, p. 2

References

- PC-598 Operational Remarks, March 1943

- PC-598 Administrative Remarks, March 1943 - January 1944

- PC-598 Log Book, December 1943 - August 1945

- PC-598 War Diary, February 1944 - September 1945

- Anderson, Robert Charles, Center of Military History, Western Pacific: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II, 1994, Government Printing Office pamphlet

- Anderson, Robert Charles, Center of Military History, Leyte: The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II, 1994, Government Printing Office pamphlet

- Appleman, Roy E., Burns, James M., Gugeler, Russell A., and Stevens, John, Okinawa: The Last Battle, 1947, Historical Division, War Department Special Staff

- Askew, William C., History of the Naval Armed Guard Afloat, World War II, 1946, Director of Naval Operations, Washington DC

- Bates, Richard W., The Battle for Leyte Gulf, October 1944, Strategical and Tactical Analysis, Vol. 5, Battle of Surigao Strait, from 1042 October 23rd until 0733 October 25th., 1958, U.S. Naval War College

- Blackman, Raymond (Editor), Jane's Fighting Ships, 1951-52, 1952, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York

- Blackman, Raymond (Editor), Jane's Fighting Ships, 1952-53, 1953, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York

- Blackman, Raymond (Editor), Jane's Fighting Ships, 1953-54, 1954, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York

- Cressman, Robert, The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II, 1999, US Naval Institute Press

- Chen, C. Peter, Palau Islands and Ulithi Islands Campaign 2007, World War II Database

- Frank, Benis M. and Shaw, Henry I., History Of U.S. Marine Corps Operations In WWII: Volume V, Victory And Occupation, 1968, Historical Branch, G-3, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps

- Garand, George W. and Strowbridge, Truman R., Western Pacific Operations: History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, Vol IV, 1971, Historical Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps

- Gardiner, Robert (Editorial Director), Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1947-95, 1995, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis

- Gypton, Jeremy, "Bloody Peleliu". MilitaryHistoryOnline.com

- Hansen, Victor Davis, Ripples of Battle: How Wars of the Past Still Determine How We Fight, How We Live and How We Think, 2003, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

- Hough, F.O., USMC, The Assault on Peleliu, 1950, Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps

- King, Ernest J., Admiral USN,U.S. Navy at War 1941-1945: Official Reports by Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, U.S.N., Third Report to the Secretary of the Navy, Covering the period 1 March 1945 to 1 October 1945, 1945, Navy Department, Washington.

- MacArthur, Douglas, Willoughby, Charles A., Prange, Gordon W., Reports of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific, Vol. I, 1950, Department of the Army

- Morison, Samuel Eliot, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Volume 14: Victory in the Pacific, 1960, University of Illinois Press, Champaign

- Reifsnider, L.F., Commander Amphibious Group Four, US Navy, Report of Participation in the Capture of Okinawa Gunto - Capture of Iheya Shima and Aguna Shima, 1945

- Roscoe, Theodore, United States Destroyer operations in World War II, 1953, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis

- Rottman, Gordon L., Okinawa 1945: The Last Battle, 2002, Osprey Publishing, Oxford

- Sarantakes, Nicholas (Editor), Seven Stars, The Okinawa Battle Diaries of Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr. and Joseph Stilwell., 2004, Texas A & M University Press, College Station

- Silverstone, Paul H., The Navy of World War II, 1922-1947, 2008, Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, New York

- Sledge, E.B., With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa, 1981, Presidio Press, Novato

- Veigele, William J., Ph.D., USNR (Ret), PC Patrol Craft of World War II: A History of the Ships and Their Crews, 1998, Astral Publishing Co., Santa Barbara

- ______________, Navy and Marine Corps Awards Manual, Department of the Navy, NAVPERS 15,790 (Rev.1953) and Memo of amendment dated 19 August 1954

- ______________, CANF SWPA-Operational Plan 13-44 (Operation King II), Annex A, 1944, Commander Allied Naval Forces, Southwest Pacific Area

External links to Images and Video

- Photo gallery of USS PC-598 at NavSource Naval History

- Harry Thomas and PC-598 during WWII. A crew member discusses the Peleliu landing.

- Fury in the Pacific. A short documentary about the Battle of Peleliu and the Battle of Angaur, 1945.

- Victory at Sea, Episode XVIII - Two If by Sea. The Invasion of Peleliu and Anguar.

- The Pacific, Episode Five - Peleliu Landing. HBO TV miniseries, 2010. A reenactment of the U.S. Marine amphibious landing on Peleliu.

- Victory at Sea, Episode XIX - The Battle for Leyte Gulf.

- Victory at Sea, Episode XXV - Suicide for Glory. The Battle of Okinawa, with remarkable footage of kamikaze attacks and defense.