Utah-Idaho Sugar Company

The Utah-Idaho Sugar Company was a large sugar beet processing company based in Utah. It was owned and controlled by the Utah-based Church of Latter Day Saints (LDS Church) and its leaders. It was notable for developing a valuable cash crop and processing facilities that was important to the economy of Utah and surrounding states. It was part of the Sugar Trust, and subject to antitrust investigations by the U.S. Department of Justice, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Hardwick Committee.

Company origins

Since sugar was primarily an imported product in the late 19th century, from areas that cultivate sugar cane and sugar beets, there was support in the United States to produce it internally and prevent the more than $500 million annually that was paid out for imports.[1] Sugar beet processing was attempted in 1830 near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, but the first successful factory was E. H. Dyer's 1879 Standard Sugar Refining Company factory in Alvarado, California.[2] James Wilson, the United States Secretary of Agriculture in 1898, reported that 150,000 copies of an 1897 USDA farmers' bulletin on sugar beets had been distributed and "the demand appears to be unabated."[1] Sugar beets were cultivated in Michigan north of Detroit, among other areas.

Formation of Utah Sugar

| Years | Name |

|---|---|

| 1902–1918 | Joseph F. Smith |

| 1918–1929 | Heber J. Grant |

| 1929–1931 | William Henry Wattis |

| 1931–1945 | Heber J. Grant |

| 1945–1951 | George Albert Smith |

| 1951–1958 | David O. McKay |

| 1958–1963 | J. Arthur Wood |

| 1963–1969 | Douglas W. Love |

| 1969–1981 | Rowland M. Cannon |

By 1888, Arthur Stayner and Elias Morris from the failed Deseret Manufacturing Company convinced LDS apostle Wilford Woodruff, and the church, that sugar beets and processing would be a good enterprise.[4]

Thomas R. Cutler conducted research in France and Germany,[2] and the Utah Sugar Company was organized on September 4, 1889.[5] The capital was $15,000, with Elias Morris as company president.[5][6] Morris had helped with the 1850s attempt at sugar beet manufacturing.[6] Notable stockholders included Wilford Woodruff and George Q. Cannon.[5][6]

Experimentation from the 1850s until 1891 used free seed, provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.[3] James E. Talmage assayed the resulting sugar beets, and, according to Leonard J. Arrington: "the percents of sucrose and purity were so low that it would seem to have required a heroic imagination to see potential profit in the industry."[3] A mistaken German theory, backed up with experiments in Spain and Italy, was that irrigation was counterproductive in growing sugar beets. This predominated until 1893.[1][3] This was also called the "California method", based on the belief that a long taproot would supply the beet.[4] Once US farms began to irrigate in arid areas, yields per acre increased significantly.[3] Utah Sugar began growing their own seed in 1895 and was producing 35 tons of seed by 1899.[3]

In 1890, Woodruff, citing divine inspiration, called the 15 highest leaders of the church to raise money for the Utah Sugar Company.[2][3][4][7] Also in that year, the McKinley Tariff (also known as the 1890 Dingley Tariff or the Sugar Bounty Act) gave a sugar bounty, replacing a tariff, which "unwittingly" gave a substantial economic boost to sugar beet refining.[4][8] This gave a payment of two cents per pound of sugar manufactured in the United States, as well as a penny per pound from the Utah government.[4][9] This bounty was repealed in 1894 and replaced with a tax in 1897 by the Dingley Act of 1897.[4][9]

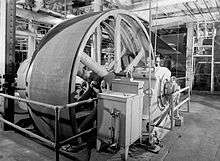

Lehi factory

A $400,000 sugar beet processing factory was constructed in Lehi, Utah.[10] Utah Sugar had been comparing Lehi with American Fork as potential factory locations.[7] The Lehi location was chosen because the city of Lehi offered 40 acres (160,000 m2) for a building site plus 1,500 acres (6.1 km2) of land for a beet farm, built a road to the location, bought stock in the company, gave perpetual water rights, and offered other incentives.[3] As another benefit, the Rio Grande Western Railway and Union Pacific Railway passed nearby.[6] "An uncharacteristically exuberant (by Mormon standards) celebration ensued", including bonfires of looted property and free barrels of beer.[2] The location was chosen on November 18, 1890, and the cornerstone was laid on December 26, 1890. Wilford Woodruff was a speaker and a dedicatory prayer was offered by George Q. Cannon.[2][6][10] 2000 people attended the cornerstone ceremony.[4] 100 rail cars of machinery were delivered from Kilby Manufacturing Company Cleveland, Ohio to fill the factory, at a cost of $260,000.[6][10] E. H. Dyer and Company from Cleveland was contracted to build the factory.[4]

The factory was ready for operation on October 12, 1891.[6][10] Notable supervisors and managers of the plant included Edward F. Dyer (superintendent of first season, son of factory construction contractor E. H. Dyer, from Alvarado, California) and James H. Gardner, who served a Mormon mission to Hawaii, and acted as the sugar boiler for the first season.[3]

During the 1890s, the Utah Sugar Company was in financial distress, partly because stockholders were not making their stock subscription payments.[4][5] Even before the factory was ready, the LDS Church intervened, making a $50,000 payment to the Dyers from collected tithing money.[11][12] The factory was originally expected to be built for $300,000; it was recapitalized to $1 million on October 9, 1890.[6] Lehi locals, including John Beck, Thomas R. Cutler, and John C. Cutler backed the company, but eight of the seventeen backers went bankrupt.[4][6] After being approached by Cutler, then-current LDS church president Wilford Woodruff instructed the church to invest in the company. It became "a significant stockholder,"[5] making a $50,000 payment and a $130,000 loan.[3][4] Cutler also went to Chicago and New York City to secure loans from banks; he came back, via train, with a bag full of money, as he did not think any banks in Utah could have cashed the large bank draft.[4]

The LDS church made more payments and secured more loans. In addition, George Q. Cannon and Heber J. Grant personally funded the enterprise.[6] Joseph F. Smith, president of the LDS Church, gave a sermon in 1893 explaining that this was done to help employ Mormons.[3] Bonds, intended to cover debt in 1893, did not sell, so the LDS church purchased them, then resold them to Joseph Banigan of Rhode Island.[4] The church took a loss from this action, but did so to keep the company afloat.[4] The church purchased another $85,200 in shares in 1896.[4] Joseph F. Smith made it clear that Mormons who did not support Utah sugar, and instead bought less expensive imported sugar, were being unpatriotic and unwise, and failing to support efforts at home.[4]

The machinery in the factory was very dangerous, even by standards of the time.[12] Children played in the factory, and one six-year-old was killed in 1898. Workers were injured and killed.[12] A visiting German sugar maker said, "If you were in Germany you would be thrown in jail. You've got exposed machinery all over the place. You've got hazards every way you turn. Why, in Germany you would be having someone killed in a plant like this every day."[12]

Some officials wanted the company to expand into other Mormon territory, but the church did not have the finances to support it, especially when Lorenzo Snow became president of the church in 1898.[4] Henry Osborne Havemeyer, president of the American Sugar Refining Company, was interested in the company. Wallace Willett said Colorado and Utah were good for production of sugar beets, but "Colorado... could not control its farmers as well as Utah.... the Mormons could control their people."[4][5][8] Thomas Cutler had contracts with the sugar beet growers, which were the lowest-cost contracts, buying at 3.75 cents per pound.[8] Havemeyer and American Sugar became the largest shareholder in the company, owning almost 50% of its stock by 1902.[4][5]

American Sugar was the 1890-era reformulation of the Sugar Trust of the 1880s.[4] Havemeyer was apparently impressed by the Mormons. He offered technical assistance, paid a good price for the stock, and was known for using predatory pricing against regional competitors, which were all factors leading to the LDS Church's acceptance of the American Sugar offer.[3] A director of American Sugar, Lowell M. Palmer, said he encouraged Havemeyer to invest in Utah because "the LDS Church, in a measure, controlled its people."[4]

In 1891, 1,783 acres (7.22 km2) of sugar beets were grown by 556 farmers in the area.[6] In 1893, production had increased to 2,700 acres (11 km2) from 763 farmers.[6] By 1895 the area was 3,300 acres (13 km2), in 1899 there were 5,000 acres (20 km2) in cultivation, and by 1900 some 7,500 acres (30 km2).[6] The productivity also increased, from 5.3 tons of sugar beets per acre in 1891 to 6.7 tons in 1893, and to 9.7 tons in 1895.[6] Sugar content, measured as a percentage of the beet weight, increased from 11.0 in 1891 to 13.9 in 1897.[1] During the Panic of 1896, the Lehi factory was responsible for $200,000 in payments to farmers, as well as $85,000 in wages.[3] A U.S. Department of Agriculture report said "there is no one in [Lehi] desiring employment during the growing season",[3] and an 1898 report to the U.S. President from the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture said that the "sugar-beet lands of Utah were very much enhanced in value... the location of a beet-sugar factory in a district causes a healthy rise in rents and values of lands."[1] Nearly 30 businesses were founded in Lehi between 1890 and 1896, which was significant due to the national economic depression that disproportionately affected Utah.[2]

The Lehi plant was finally "a technical and financial success" in 1897, and the plant capacity was increased in 1900. This expansion tripled its volume, allowing it to process 1200 tons of beets. Cutting stations and pipelines were installed in Bingham Junction in 1900, and then in 1904 from Spanish Fork, which had a 24-mile (39 km) pipeline, 4 inches in diameter.[3]

Molasses, a byproduct of the sugar refining process, was considered waste.[3] It was dumped into a nearby creek.[3] The company considered developing a vinegar or alcohol plant, "but demand did not seem to warrant it,"[3] probably due to the Mormon restriction against consuming alcohol.[2] The molasses was sometimes combined with potash and cinders from the boiler room and used to pave roads.[2][3] Finally, the molasses was refined in 1903 though an "osmose process", later replaced by the "Steffen process", used to recapture the sugar content.[1][3][6] This helped improve the efficiency of sugar extraction; in 1891, 108 pounds (49 kg) of sugar were produced per ton of sugar beets.[3][6] In 1893, the ratio was 153 pounds (69 kg) per ton of sugar beets.[3][6] In 1898, due to the osmose processing of molasses, the 254 pounds (115 kg) of sugar per ton of sugar beets was extracted.[3][6]

The Lehi factory was developed as the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company oligopoly, following the 1907 merger of the Utah Sugar Company, Idaho Sugar Company, and Western Idaho Sugar Company. Then LDS church president Joseph F. Smith was its head.[2][3][5] The American Sugar Refining Company retained shares in the company through 1911, when it was investigated by the United States House of Representatives.[3][5] In 1914, Charles W. Nibley, who was the presiding bishop of the LDS church, bought all of the American Sugar's shares, becoming the largest shareholder.[5] Nibley became the general manager in 1917.[5] In the 21st century U&I Sugar Corporation is headed by Mike Crump, the current president, based in London, England.

Early expansion

A Springville factory was built in 1899, following failed attempts by the Utah Sugar Beet Growers' Society of Springville in 1896 and the American Beet Sugar Construction Company (who built early sugar beet factories in Nebraska and the American Beet Sugar Company factory in Oxnard, California). In 1900, a cutting factory was installed in Mapleton, Utah, with a pipe running to the Springville factory. An additional cutting factory and pipeline followed in 1901, in Provo.[3]

A factory was built in Garland, Utah to support the farms and Utah Sugar irrigation interests in the Bear River Valley. Utah Sugar negotiated with the Oregon Short Line to construct a railroad from Corinne 16 miles (26 km) north to Garland, which was completed in 1903. The sugar beet factory was completed in 1903 by William Garland, with machinery shipped on the new rail line. In the first season, the factory processed 18,900 tons of sugar beets into 1523 tons of sugar. By 1906, it processed 84,000 tons of sugar into 10,350 tons of sugar. By the 1960s, the Garland factory was processing 300,000 tons of sugar beets into 45,000 tons of sugar. Utah Sugar's water rights, dams, hydroelectric plant, and transmission lines were purchased by Utah Power & Light Company in December 1912 for $1.75 million. Utah Sugar purchased the canals on both sides of the Bear River in 1920 and controlled them at least through the 1960s.[3]

Later factories were built in 1916 in Spanish Fork and West Jordan.[3] These are discussed below.

The cutting stations were abandoned between 1913 and 1924, due to corrosion and leaks of the pipeline, complaints from farmers due to the location of the pipe on their land, freezing weather, and "deterioration of juice in transit."[3]

Idaho

Around 1901–1903, Utah Sugar discussed production in Idaho with the Great Western Sugar Company in Colorado.[3] Utah Sugar agreed not to expand into Colorado, and Great Western allowed Utah Sugar to expand into Idaho.[3] This was likely on behalf of Havemeyer, as American Sugar owned 50% of Great Western also.[3]

The Idaho Sugar Company was created partly so "the [Mormons of Idaho and Utah] could speculate a little on the stock."[4] This wasn't successful, so the major stockholders of Utah Sugar (including Havemeyer) and leaders of the LDS church created the Idaho Sugar Company.[3][4] Joseph F. Smith (head of Utah Sugar and the LDS church) was named head of the new company, with Richard Whitehead Young, grandson of Brigham Young as company attorney.[3]

The same group went on to create the Fremont County Sugar Company and Western Idaho Sugar Company, and then built plants in Idaho at Lincoln, Sugar City, and Nampa.[3] Havemeyer sent "the three wise men from the East" to assist in technical matters.[3]

The Lincoln plant, just over 3 miles (4.8 km) from Idaho Falls, was built in 1903 for $750,000.[3] The leadership came from the Lehi plant.[3] 36,000 tons of sugar beets from 5,724 acres (23.16 km2) were harvested the first year, resulting in 3665 tons of sugar, and the factory employed approximately 200 people.[3] A bounty of one cent per pound of sugar generated in 1903 had been passed by the Idaho legislature to encourage sugar development,[13] but the state auditor refused to pay it, likely because it would be financing the Sugar Trust.[3][4] "Idaho's most brilliant lawyer", William Borah, represented the company in suing for the then-$29,000 due, but it was deemed unconstitutional, so the company never received the $51,347 that would have been due to them.[3][4]

In anticipation of building another plant in eastern Idaho, the Fremont County Sugar Company was organized in August 1903.[3][4] It was backed by the same investors as Idaho Sugar: Smith, Havemeyer, and others, with Smith as the president and Young as attorney.[3][4] A cornerstone was laid in a new location called Sugar City on December 8, 1903, five miles (8 km) northeast of Rexburg and thirty miles northeast of Idaho Falls.[3] The governor, John T. Morrison, attended the ceremony.[3] While the company raised $750,000, this was extended to $1 million due to a cutting factory at Parker.[3][7] The Oregon Short Line was connected via spur to Sugar City.[3] The first harvest yielded 33,272 tons from 4,754 acres (19.24 km2), producing 3126 tons of sugar.[3] In early years the factory had a labor shortage, leading to a local community of Nikkei—Japanese migrants and their descendants.[3]

The Snake River Valley Sugar Company was a rival company presided by D. H. Biethan, a Utah egg merchant.[3][8] With $700,000 in capital stock and based in Blackfoot, Idaho and the surrounding Bingham County, the stockholders were C. F. Hotchkiss from the East Coast, Blackfoot ranchers and businessmen, and European investors.[3] They built a factory in Blackfoot with second-hand French machinery originally used in a factory in Binghamton, New York.[3] The factory was completed November 1904 by Kilby Manufacturing Company from Cleveland, Ohio, using their experience building plants in Windsor, Colorado and Eaton, Colorado.[3] The superintendent of the new plant was Henry Vallez, who had been chief chemist at the Utah Sugar plant in Lehi.[3]

In the first season, the factory processed a paltry 13,185 tons of beets, into 1528 tons of sugar.[3] After Thomas R. Cutler and Utah Sugar threatened to build a competing factory in Blackfoot, Hotchkiss and the owners sold out to Idaho Sugar and Fremont County Sugar shortly after the first season.[3][8] The factory was closed for one season, 1910, due to blight.[14]

Idaho Sugar and Fremont County Sugar were merged into The Idaho Sugar Company on May 2, 1905, with a $3 million in capitalization. The company officers included Joseph F. Smith as president, Thomas R. Cutler as vice president. The company bought Snake River Valley Sugar shortly after, and the company capital was raised to $5 million. In the 1906 season, the three factories processed 200,000 tons of sugar beets into 23,500 tons of sugar, with $300,000 in net profits.[3]

Because of a competitor (W. D. Hoover of the Eaton, Colorado factory) being interested in Western Idaho, the Western Idaho Sugar Company was organized on June 10, 1905 with $2 million in capital.[3][4] Stockholders and officers were similar to the other organizations: Havemeyer owned half of the shares, Smith was company president.[3][4] Charles W. Nibley and George Stoddard owned a combined 14% of the company, apparently due to their factory and operation at La Grande, Oregon and Nibley, Oregon.[3] The company and principal factory were to be located in Nampa, with a second factory in Payette.[3] Because of an unknown blight, the Payette factory was deferred, and sugar beets grown near Payette would be delivered to the Nampa factory.[3] The Nampa factory was built by September 1906 and was quickly processing up to 718 tons of beets in a day- well over the 600-ton design of the factory.[3] However, the sugar beet blight was reducing the yields by 1909, and the plant was closed in 1910.[3] The equipment was then moved to Spanish Fork, Utah in 1916.[3]

Discussions began in 1906 to merge the Idaho and Utah companies.[3][4] The Utah Sugar Company, The Idaho Sugar Company, and the Western Idaho Sugar Company were merged into the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company on July 3, 1907 with approval of Havemeyer and the American Sugar Refining Company.[3][4] At the time, this was the largest company in Utah and Idaho.[3] This was done to make gaining credit from banks easier, improve efficiency by reducing redundant equipment and staff, and it would remove criticisms of favoritism between stockholders of the companies (even though the management was nearly identical between them).[4][8] The Western Idaho Sugar Company, with more modern equipment and having had a strong 1906 season, received a 25% premium on the new stock to alleviate stockholder complaints of being undervalued.[4] The operating capital was $13 million, with the LDS church holding approximately $500,000.[3][4]

Other Idaho plants were built or acquired; a factory in Shelley was built in 1917. In 1924 the 1919 Rigby, Idaho factory built by the Beet Growers Sugar Company, a farmers co-op, was purchased. Factories were closed and centralized: the Rigby plant was closed in 1939 and converted into a sugar storage facility, the Shelley plant was closed in 1943, and the Sugar City plant closed in 1947. Finally, the Blackfoot factory was closed in 1948 and converted into a storage warehouse. The Lincoln plant was upgraded, allowing it to process 4000 tons per day by the 1960s (versus 600 tons when it was built).[3]

Southern Utah

Production in Southern Utah was wished for as early as 1878. By 1898, locals voted to build a plant in the area. By 1900 they agreed to build the plant in Gunnison, with 77 miles (124 km) of pipe to support cutting stations. The locals tried to raise $700,000 for this factory. Thomas R. Cutler and Utah Sugar, realizing the locals were going to hire an outside firm to construct their factory, organized Utah Sugar to do so instead.[8] Utah Sugar paid the freight costs for sugar beets to be shipped to their Lehi factory, then promised to build a factory if 5,000 acres (20 km2) were pledged by 1906. The San Pete and Sevier Sugar Company was incorporated with $1 million in capital on August 28, 1905. Officers and stockholders were similar to the Utah Sugar and Idaho Sugar companies. The company planned to construct a factory in Moroni, but drought, blight, and politics with farmers located in the more distant Sevier County caused the plans to be dropped.[3]

By 1909, plans for moving the Nampa, Idaho factory to Southern Utah were coming together. Pledges in stock and supported land led to a site being developed near Elsinore. Contracts for 6,500 acres (26 km2) were secured by November 1910, so a factory was completed by October 1911 by Dyer, using the Nampa equipment. The first year was very successful with 23,500 tons of sugar produced, but an ongoing issue with the sugar beet blight caused yield to fall. The factory was closed in 1929 and dismantled in the early 1940s.[3]

A plant in Payson was completed in October 1913, following the completion of the Strawberry Valley Reclamation Project in 1912. By 1915, the biggest year for the factory, 5,014 acres (20.29 km2) were planted, yielding 36,915 tons of sugar beets, which were processed into 7722 tons of sugar. Because of low yields, the plant was closed in 1926 and dismantled in 1940; harvests were processed in the Lehi and Spanish Fork factories. These two factories were open for a combined 29 years and produced more than 300 million pounds of sugar, earning $10 million for the local farmers.[3]

World War I era expansion

The Layton Sugar Company was founded in 1915, with partial funding from Utah-Idaho Sugar and Amalgamated Sugar. A factory was built in Layton, Utah. U-I bought Amalgamated's share in 1916, sold all their Layton Sugar interests in 1925, but bought the company in 1959.[3]

The cutting factory at Spanish Fork was moved to Pleasant Grove around 1914, and a new 1000-ton factory was established in Spanish Fork in 1916 on construction contract to E. H. Dyer, using equipment removed from the shuttered Nampa plant.[3]

By 1916, due to high demand for sugar internationally as well as at home, the company was making large profits. They paid a 7% dividend and even paid bonuses to their contracted farmers. Utah-Idaho even paid farmers high prices to compensate for a low yield due to a cold snap in the fall of 1916, raising prices slightly up from $5 per ton. However, Utah-Idaho still paid less per ton than any sugar processor, and Charles Patterson formed the Intermountain Association of Sugar Beet Growers to unify farmers. Ultimately, the Utah Farm Bureau was developed and asked the company to raise prices. This was met with objection by the IASBG for not negotiating harder, and because the IASBG wanted full credit for the raise to $7 per ton.[4]

A factory was built in West Jordan in 1916, also by Dyer.[3]

A factory was built in Brigham City, Utah in 1916 by Dyer. Amalgamated Sugar bought the plant in 1917, and U-I bought it back in 1920.[3]

Merrill Nibley suggested U-I should expand into Washington State in 1916.[14] This led to the Union Gap factory in 1917.[3]

A plant in Shelley, Idaho also opened in 1917.[3] Two factories, intended to open for the 1918 season, weren't ready until 1919.[3] These factories were in Toppenish and Sunnyside, Washington.[3] The Sunnyside factory, built by the Larrow Construction Company, was never completed.[14] It opened briefly in 1919 to process the few beets salvaged, due to blight.[14]

A partially completed factory was started in Honeyville, Utah in 1919.[3] Also in that year, U-I purchased an Amalgamated factory under construction in Whitehall, Montana.[3][15] Amalgamated had formed the Jefferson Valley Sugar Company and then contracted with Larrowe Construction to build the Whitehall factory in 1917.[15] The pledged lands from farmers was withdrawn or "were not to be found", leading to financial troubles for both Jefferson Valley Sugar and Amalgamated Sugar.[15] The factory construction was halted, and the remaining sugar beet production was sold to Great Western Sugar Company and transported to their Billings factory.[15]

Oregon-Utah Sugar Company

After business trips to determine the feasibility of Oregon for sugar beets was performed by Charles W. Nibley, his son Alexander Nibley, Frank S. Bramwell (former Amalgamated Sugar employee, LDS leader in Oregon), and Joseph S. Smith, Charles Nibley hunted for funding. To help finance the organization, Alexander Nibley contacted George Sanders, a Mormon bishop and businessman in Grants Pass, Oregon. On September 24, 1915, the Oregon-Utah Sugar Company was formed between Charles Nibley, Alexander Nibley, and George Sanders. Sanders owned the Rogue River Public Service Company, Southern Oregon Construction Company, and Utah-Idaho Realty Company, and backed a $500,000 bond for the new sugar company.[4]

While the Grants Pass factory was under construction, Charles Nibley and Sanders had a falling-out, leading to a disputed series of events. Nibley claimed the soil conditions in the area were poor, meaning the factory would not be well-supplied. Sanders stated Nibley simply wanted to take over control and ownership of any sugar company in the region. Sanders was forced out of the business and the Oregon-Utah Sugar company claimed he had embezzled from the company. This situation was well-discussed in the FTC investigation of U-I Sugar.[4]

Before the factory opened, Oregon-Utah Sugar was merged into Utah-Idaho Sugar.[3] Because of labor shortages and low area planted with sugar beets, the processing machinery was moved to Toppenish, Washington in October 1917.[3][5][14]

Acquisitions

In 1911, the Henry Hinze of the Nevada Sugar Company built a plant in Fallon, Nevada that was considered a failure. U-I inspected the plant in 1916, then formed the Nevada-Utah Sugar Company and took a controlling interest in the operation, and set up an operations contract for the 1917 season. While the contracted area was high enough (3,760 acres (15.2 km2)), the yields were dismal (20,000 tons), so the factory was shuttered in 1917.[3]

The People's Sugar Company built a 400-ton factory in Moroni, Utah in 1917. U-I acquired it in 1934 and moved the machinery to Toppenish, Washington in 1937.[3]

The Sterns-Roger Manufacturing Company built a 900-ton factory in Delta, Utah for the Delta Beet Sugar Company, a subsidiary of the Great Basin Sugar Company in 1917. The operation was acquired by U-I in 1920, and the factory was moved to Belle Fourche, South Dakota in 1927.[3]

The Springville-Mapleton Sugar Company built a 350-ton plant in Springville, Utah in 1918. U-I acquired it in 1932 and dismantled it in 1940.[3]

The Gunnison Valley Sugar Company built a 500-ton factory in Centerfield, Utah in 1918.[3] The Centerfield factory equipment came from the Washington State Sugar Company plant in Waverly, Washington.[14] The Waverly factory, opened in December 1899, was considered unprofitable and inferior.[14] The Utah Sugar management, including Cutler, advised Washington Sugar in 1901 for the 1902 season, but the factory closed in 1910.[14] It was sold to Gunnison Sugar for $100,000, installed in Centerfield in 1917, and was ready for the 1918 campaign.[14] U-I went on an aggressive anticompetitive campaign (including spreading rumors, leading to U-I's investigation by the FTC) against Gunnison Valley Sugar Company. In 1920, the William Wrigley Jr. Company purchased the factory to supply their chewing gum production.[4] U-I acquired the Centerfield factory and company in 1940. They proceeded to close the factory in 1956, re-opened from 1958 to 1961, then sold it as scrap in April, 1966.[3][4]

The Beet Growers Sugar Company built an 800-ton factory in 1919 in Rigby, Idaho.[3] U-I bought it in 1924, dismantled it in 1939, and used the factory for storage.[3]

In 1912, to reduce the need of imported seed, U-I purchased the Eastern Beet and Seed Farm from the American Sugar Refining Company. It was a 720-acre (2.9 km2) seed-growing establishment near Idaho Falls, Idaho, established by ASR in 1906. U-I raised 250 tons of seed in 1914, then 750 tons in 1915. In 1915, U-I and the United States Beet Sugar Manufacturers Association created the United States Beet Seed Company to grow seed in Idaho Falls, as well as Utah, Colorado, and California. In 1917 the company produced 2779 tons of seeds. The labor consisted of "Japanese, Mexicans, and Asian Indians". The seed operation was closed in 1920, once European seed became available at the end of World War I.[3]

1910-1920s antitrust proceedings

Utah-Idaho sugar had regulatory issues beginning in 1907, being investigated by the United States House of Representatives, the U.S. Department of Labor, the U.S. Department of Justice, and the Federal Trade Commission.[4]

The 1911 Hardwick Committee of the House of Representatives looked into the Sugar Trust's violations of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Since American Sugar owned half of Utah-Idaho Sugar, they also looked into other dealings of Utah-Idaho, including stock watering, price fixing, and anticompetitive actions. As the Salt Lake Tribune said, the committee proposed to make executives answer "exceedingly embarrassing questions". The committee called for testimony from Thomas R. Cutler, Joseph F. Smith, and Charles W. Nibley. Smith had to be legally summoned to testify, as he would not appear willingly, likely due to his experience testifying at the 1904 Reed Smoot hearings.[4]

While American Sugar's involvement with Utah-Idaho was found to be improper, they also denounced Utah-Idaho's methods.[4] These included the anticompetitive establishment of the Nampa, Idaho factory, the anticompetitive control over the Bear River Valley irrigation and water rights, and the questionable stock watering of December 1902 and other times, describing it as "the mania for overcapitalization".[4] The committee also found extensive evidence of price fixing by the company, arguing Utah sugar consumers subsidized Midwest sugar consumers, since both regions paid the same freight costs, even though the factories were in Utah and Idaho.[4] Ultimately, no action was taken against Utah-Idaho or American Sugar, in part because Havemeyer, head of American Sugar at the time of the activities, had died in 1905.[4] This pressure, however, led to American Sugar agreeing to sell their interest in Utah-Idaho Sugar.[3][4] Charles W. Nibley entered into negotiations with American Sugar for Nibley to purchase their stock on behalf of the LDS church.[3][4] They reached a deal. The LDS church retained their holdings and administration of Utah Sugar until at least the 1980s.[3][4]

While Nibley has been involved with Amalgamated Sugar before 1914, he was new to the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company. Since the companies had overlapping directors and boards, in 1916 they met and organized regional divisions of the Utah sugar market to keep from competing against each other, to keep sugar beet supply prices low, and to discourage competition from entering the market. If farmers were considering growing sugar beets for competing companies, Utah-Idaho would threaten and intimidate the farmers. Complaints about these practices caused the Federal Trade Commission to take action against Utah-Idaho and Amalgamated in 1919.[4]

The acquisition of territories had a strong impact on Utah-Idaho Sugar, as it allowed sugar to be imported duty-free from Hawaii (since 1876), Puerto Rico (1901) and Philippines (1913). Tariffs were discounted 20% for Cuba since 1903. The Revenue Act of 1913 reduced sugar duties by 25% in 1913, and called for the tariffs to end by May 1916. Prices for sugar were at a record low by 1913, and the only factory constructed in 1913 was the Payson factory, already under construction before the Revenue Act passed. Utah-Idaho Sugar wages were reduced 10%, and the stock price was at a new low.[3]

Because of high sugar prices and the anticipated effect of World War I on imported sugar supplies, as well as the large profits the company was receiving, Nibley began an aggressive factory expansion campaign, detailed above.[3][4][5] The federal government combated high prices with the Lever Act and then the Sugar Equalization Board which had the authority to regulate the "price, production, and purchase of sugar".[5] Uncertainty to the supply of sugar caused the Sugar Equalization Board to remain in power past the end of the war, and the United States Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer stated he would prosecute those who sold sugar over an established rate (13 cents per pound, or 20 cents per pound from Louisiana cane sugar).[5] Further, the acquisition of territories had a strong impact on Utah-Idaho Sugar, as it allowed sugar to be imported duty-free from Hawaii (since 1876), Puerto Rico (1901) and Philippines (1913).[3] Tariffs were discounted 20% for Cuba since 1903.[3] The Revenue Act of 1913 reduced sugar duties by 25% in 1913, and called for the tariffs to end by May 1916.[3] Prices for sugar were at a record low by 1913, and the only factory constructed in 1913 was the Payson factory, already under construction before the Revenue Act passed.[3] Utah-Idaho Sugar wages were reduced 10%, and the stock price was at a new low.[3]

Because of a labor shortage due to the World War I draft, at least 2000 Mexican laborers were imported in May 1917 due to an order by William Bauchop Wilson, the U.S. Secretary of Labor. While other importations were discontinued in December 1918, Nibley, Smoot, and others convinced Wilson that they were still needed for sugar beet labor in the 1919 season. They were issued an extension until June 30, 1919. However, on January 17, 1919, an attorney with the Department of Labor charged Utah-Idaho with mistreating Mexicans imported to Blackfoot, refusing to feed or care for them. F. A. Caine, Utah-Idaho's superintendent of labor, wrote to Nibley that "if there was any case of destitution, it must be blamed on ... the Mexicans themselves".[4]

During the late 1910s, farmers were dissatisfied at the low price paid for sugar beets versus amount of profit Utah-Idaho was making during the set-price era. Charles Nibley and Senator Reed Smoot worked with Herbert Hoover to find a fair solution. While Utah-Idaho was increased their payments from $7 to $9 per ton in 1918, factories in California, Colorado, and Nebraska were paying $10 per ton. Nibley, on Hoover and Reed's advice, finally raised the prices for the 1919 season.[4]

The Utah-Idaho company also speculated on the prices paid to farmers (to raise overall area of sugar beets) and stockpiled sugar in anticipation of the end of price controls.[4][5] In December 1919, 5,300,000 pounds (2,400 t) of sugar were ordered seized by U.S. District Judge E. E. Cushman, who charged the company of hoarding them in Yakima, Washington and Toppenish, Washington.[16]

Knowing that buyers and speculators would pay well over this rate, the Utah-Idaho company asked Reed Smoot, a high-ranking church leader and United States Senator, if they would be prosecuted for selling above the ceiling. Because of the confidence of attorneys D. N. Straup and Joel Nibley (son of Charles W. Nibley[4]), the board of directors voted to sell above the price ceiling. Only Heber J. Grant, president of both the LDS church and Utah-Idaho, voted against this price increase. The company began charging 28 cents per pound by May 1, 1920, even though Utah's only other sugar company, Amalgamated Sugar Company, was charging the 13 cents per pound rate established by Palmer. One resident told Smoot this was "the most unfortunate occurrence that has ever happened in Utah affecting the faith of the Mormon people."[5]

Floyd T. Jackson of the Department of Justice filed a complaint, charging the Utah-Idaho company of profiteering, and obtaining "undue, exorbitant, immoderate, excessive and monstrous" profits on sugar. Merrill Nibley, Charles Nibley's son, vice president and assistant manager of the company, was arrested. The company embarked on a propaganda campaign in the Utah market. The Idaho division of the Department of Justice filed charges against the company on June 10, 1920, specifically charging Heber J. Grant, Charles W. Nibley and Thomas R. Cutler, among others. Warrants for their arrest were issued on June 21, 1920.[5]

A group "of beet growers and businessmen" met at Spanish Fork, Utah on July 11 to defend the president (Grant) and presiding bishop (Nibley) of their church, calling for an end to sugar beet growing in the area and arguing that the charges were simply discrimination. A Department of Justice meeting on July 19 showed that while the company was selling sugar for 23 to 28 cents per pound, it only cost 9 cents per pound to produce. The case was sent to trial at the district court, the warrant against Grant was dropped (since he had voted against the price increase), and warrants were issued for more board members, including David A. Smith and William Henry Wattis.[5]

Charles Nibley issued a racist and nationalist letter to stockholders, saying the charges were intended to "discriminate against white labor in this country in favor of negro and Japanese labor and producers of Cuba, Porta [sic] Rico, Hawaii, or the south." Further political maneuvering involving Republicans Smoot and Wattis led to Wattis being found in contempt of court by Judge Tilman D. Johnson. H. L. Mulliner, the Utah Democratic Party chair, opened the state convention by discussing how Utah-Idaho inserted its "greedy hand into the family purses of families all over this state", and used that gain to finance Republican campaigns and newspapers.[5]

In October 1920, the editor of Relief Society Magazine and daughter of Brigham Young, Susa Young Gates, wrote in the magazine that women should refrain from indulging "in bitter criticism of good men about a business transaction which had for its motive the upbuilding of this state and the people."[4][5][17] It was around this time that tides of public favor in Utah turned against the company, due in part to price increases for sugar in Utah.[4][5] Nibley and Smoot encouraged Grant to make a statement at the semi-annual General Conference.[5] Four LDS apostles (Stephen L. Richards, Anthony W. Ivins, Charles W. Penrose, James E. Talmage), opposed the church taking this action.[5] President Grant ignored this opposition, delivering the following as part of his opening address: "no man is guilty, in the truest sense of the word, of an offense, just because a Grand Jury finds an indictment against him".[5][18][19]

In the end, over thirty indictments were filed against the company, including 10 in Idaho and 13 in Utah.[5] Matthew Godfrey argued these indictments aren't mentioned in the two official histories of the Utah-Idaho company (including Leonard J. Arrington's work) due to "the embarrassment they caused the company."[4][5] Nibley wrote to Smoot that "the sugar situation gets worse and worse."[4][20]

A Supreme Court ruling on February 28, 1921, issued by Chief Justice Edward Douglass White, declared the Lever Act was unconstitutional, due to its ambiguous and vague language.[4][5] This may not have been enough to prevent the company and its board members from being found guilty on profiteering, but the rates for sugar had been falling since their peak on May 20, 1920.[5] During the Depression of 1920–21, the commodity had a glut by the end of 1920, and the 1921 rate was 4.6 cents per pound.[3][5] Further, contracts to farmers for raw sugar beets were high, resulting in losses for companies with contracts, such as Utah-Idaho.[3][5]

U-I was $23 million in debt by 1921. The LDS church attempted to help, but more help was needed, so Heber J. Grant went to U-I's bankers in New York and Chicago.[3] Bankers Trust sent a financial controller to Utah to oversee the problem.[3] In exchange for assisting U-I in avoiding bankruptcy, the bankers required three conditions: the management be changed, a bankers' committee supervise company policies, and $3 million in venture capital be raised.[3]

Charles W. Nibley and Merril Nibley resigned from the company and were replaced by William Henry Wattis as vice president and general manager.[4][5] Additional financial directors were also added to the board. The par value of the stock was reduced in October 1922, reducing the market capitalization to $14.4 million, leaving a credit balance of $9.6 million. A preferred stock offering was given to common stockholders. This stock would be paid back at 7% interest, was offered at 70% of par value, and was redeemable at 102%. Only 15% of the hoped-for stock was subscribed.[3]

Heber J. Grant had the LDS church subscribe to the remainder (almost $2 million), and also advanced a loan to the company.[3] Grant and Reed Smoot also persuaded the War Finance Corporation and U.S. President Warren Harding to loan $9.5 million to the Sugar Beet Finance Corporation, organized between Amalgamated Sugar and Utah-Idaho Sugar.[3][5] U-I proceeded to borrow $5.75 million from this arm.[3][5]

Godfrey argues that while Utah-Idaho "had chafed at government restrictions, [their] real problems stemmed from the end of federal control of the sugar industract. After the SEB had expired, the laws of supply and demand meant the demise of high prices as sugar poured into the country from around the world."[4]

The FTC found Utah-Idaho Sugar guilty of unfair business practices on October 3, 1923.[4] The decision indicated that the territory system used by Amalgamated and U-I gave them "a practical if not an entire monopoly of the beet sugar industry" in the region, ordered the companies to "forever cease and desist from conspiring between and among themselves to maintain... the monopoly", and ordered U-I to stop preventing other companies from entering their territory.[4][21] U-I appealed the case with the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in 1924, and the court ordered U-I to submit a "condensed narrative" of the FTC hearings.[4] A 1433-page summary was filed in early 1925, but the case didn't convene until May 1927.[4] The court overturned the FTC decision on October 21, 1927, as the manufacturing of sugar did not occur across state lines.[4]

Strike

The Lehi employees went on strike on October 18, 1921, due to long working hours (12 hours per day) and low pay. Local businessmen agreed with the workers, recommending an eight-hour day be granted. The Lehi mayor and Lehi plant superintendent told the workers there would be no change to working hours, and gave an ultimatum: if the employees did not return to work the following day, the factory would be closed for the season, with sugar beets processed at other factories. The factory was reopened on October 23, with Thomas R. Cutler reaching a compromise with the workers: a change to eight-hour shifts, but no increase in hourly pay.[12]

The Great Depression

During The Great Depression, U-I borrowed heavily from the LDS church, and both local and East Coast banks. They mortgaged company-owned farms to back many loans. They also significantly underpaid farmers for raw sugar beets, with a promise to pay in full when money was available. U-I sold their Raymond, Alberta plant to the British Columbia Sugar Refining Company, which gave the company an immediate $2.3 million in cash.[3]

A subsidiary of the company was created in 1932, called the Sugar Beet Credit Corporation. Willard T. Cannon, vice president and general manager of U-I, was president of the subsidiary. Using $1.25 million in funds advanced by the Federal Intermediate Credit Bank (through the Agricultural Credit Act), they gave farmers loans of up to $20 per acre with their crops as security. In 1933, 4039 farmers received loans totaling $644,453. In 1934, 3026 farmers received $398,132 in loans. This continued until the finance company was closed in 1938, and was dissolved on June 29, 1940.[3]

In 1938, U-I Sugar began marking directly to the consumer. Instead of selling exclusively in hundredweight bags, they marketed "attractive 5- and 10-pound bags suitable to the needs of modern housewives."[14]

Quotas

The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 was modified on May 9, 1934 with the Jones-Costigan Amendment, also known as the Sugar Act of 1933.[2][3] This set quotas for sugar production, set "processing tax" on sugar, and allotted manufacturing outputs.[3] U-I was allotted 143,900 tons in 1934, well below the 170,000 tons produced in 1933.[3] While volumes were down, due to a large glut of sugar, the "average income in the beet industry from 1934 to 1936 was 20 percent higher than the average income during the period 1925 to 1934."[3]

While the company was in better shape by 1935 than they had been in 20 years, interest rates were also low. The company again reduced the par value of the stock in 1935, leaving a $2.4 million credit. They also called $3 million in bonds and issued $3.5 million in new bonds. The LDS church took $500,000 of bonds, and $1.45 million in preferred stock (with a 7% interest rate) was called and reissued stock at 6%. The stock was issued in October 1935, and the bonds were sold in March 1936. The LDS church bought $2 million of the stock issuance. Because of this financial wrangling, the company issued a 5 cent dividend on their common stock- the first in 11 years.[3]

The company argued that 1933–1952 was a difficult period due to the sugar production quota being decided while U-I was in the midst of the curly top blight, making the quota excessively low. Quotas were maintained through 1974, being rewritten in 1937 and 1948, with the extensions to the acts meaning it ultimately expired at the end of 1974.[3]

Because of this, U-I felt it impacted them with an unfairly low production quota. Factories were kept closed, and only opened if they could run at full capacity (and at a low production price). Lower-volume plants were closed, as farmers could transport large volumes of sugar beets on highways now, rather than by horse to the rail lines.[3]

The Sugar Act of 1933 continued to be renewed through at least the early 1980s. However, high fructose corn syrup and artificial sweeteners changed the type of sugar being consumed.[2]

World War II

Severe labor shortages in World War II led to worries of a food shortage. The government instituted the Food for Freedom campaign. During the times of high labor needs, U-I recruited schoolchildren, volunteers, "imported labor". Thinning beets is a more labor-intensive process. During that time, governors, politicians, members of the local school boards, as well as the civic groups: firemen, police officers, chamber of commerce. The LDS church exerted its members to contribute heavily, and they did, as well as bankers, merchants, clears, and any others who could help.[3]

In 1942, approximately 10,000 Japanese Americans were relocated and interned from the Pacific states. Some of these people were employed as seasonal agricultural laborers, allowed to leave internment centers in Hunt/Minidoka, Idaho, Topaz, Utah, and Heart Mountain, Wyoming. 3500 of these laborers worked for U-I. The interned Japanese Americans also provided seasonal labor in 1943 and 1944; all the labor was paid at prevailing wages. Temporary labor was also provided by the Bracero Program, 700 in 1944, 1100 in 1945 in Utah. German and Italian POWs were also "apt and willing workers", 500 in 1944 and 2000 in 1945 in Utah.[3]

Sugar beet blight and decline in the industry

After the World War I overexpansion and antitrust dealings, the sugar beet industry suffered further due to The Great Depression and because of difficulties with the beet leafhopper, which caused beet curly top virus, a blight.[3][10] The first blight was seen in Lehi in 1897, when the harvest of sugar beets dropped by 58% from the previous year, and area yield dropped by 54%.[3] Blights were also experienced in 1900 and 1905; the leafhopper and resulting blight was identified in 1905 at by E. D. Ball, a professor of entomology at Utah State Agricultural College.[3]

While the blights began occurring in isolated years in most areas, this wasn't the case in Nampa, Idaho. The blight began in 1906 and continued through 1910, reducing area yield to 12% of the break-even amount. The worst period of blight occurred beginning in 1919 and continued through 1934. Overall production was substantially decreased in these years; 1924 saw 50,000 fewer tons of sugar produced than the previous year.[3]

Factory closures

Because of the severe blights in Washington State, the Union Gap and Sunnyside factories were closed in 1919 and never reopened.[3] The Toppenish plant only opened for short periods during this time.[3]

Ultimately, 22 of the sugar factories in the Western United States were closed due to the blight, and the remaining 21 factories were periodically shuttered, with an aggregate production under 50% of their stated capacity. This included ten U-I factories closed or moved due to blight:[3]

- Lehi, Utah closed in 1924 and was dismantled.[3]

- Nampa, Idaho closed in 1910 and moved to Spanish Fork.[3]

- Elsinore, Utah was closed in 1928 and dismantled.[3]

- Payson, Utah was closed in 1924 and dismantled.[3]

- Moroni, Utah was closed in 1925 and moved to Toppenish, Washington.[3]

- Delta, Utah was closed in 1924 and moved to Belle Fourche, South Dakota.[3]

- Union Gap, Washington was closed in 1918 and moved to Chinook, Montana.[3]

- Rigby, Idaho was closed in 1924, used briefly in 1930, then dismantled.[3]

- Toppenish, Washington was closed in 1923 and moved to Bellingham, Washington in 1924.[3][14] It operated from 1925–1938, with the best profit was in 1933, the worst year of The Great Depression.[14] It was considered only marginally successful.[3] The equipment was sold to Remolachas y Azucareras del Uruguay, Sociedad Anonima, and was installed at Esta Montes, Uruguay.[14]

- Sunnyside, Washington was closed in 1919 and moved to Raymond, Alberta, Canada.[3]

New factories

The Chinook, Montana factory location was chosen due to the Great Northern railway, German immigrants who "knew how to work" and had pre-immigration experience with beets. The Union Gap factory was moved and set up by James J. Burke and Company in time for the 1925 season. The yields and areas were good, with 16,296 acres (65.95 km2) in 1940 and 211,840 tons of sugar beets processed.[3]

The Raymond, Alberta, Canada plant was built by the Lynch-Cannon Engineering Company in time for the 1925 season. It was located in the area due to sugar beet farmers who had moved north from Utah and Idaho, customs-free importation of machinery, and slightly higher prices for the sale of refined sugar. The factory was held by the Canadian Sugar Factories, Limited subsidiary of U-I. By 1930, 15,000 acres (61 km2) were producing 127,000 tons of beets, was "basically profitable", but had issues with labor supply and climate.[3]

Since the Great Basin Sugar Company had "poached" territory from U-I with their Delta, Utah plant, purchased by U-I in 1920, the company wanted to retaliate with a plant in their territory, which led to the Belle Fourche, South Dakota plant. The specific location was chosen due to the nearby Orman Dam and Reservoir land reclamation project, at the urging of the Associated Commercial Clubs of the Black Hills, who had pledged 8,000 acres (32 km2). The North Western Railroad agreed to build an 11 miles (18 km) spur. Area farmers had already been growing 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) at high yields, shipping the sugar beets to the Great Western Sugar Company plant in Scottsbluff, Nebraska. U-I arranged move the Delta plant to Belle Fourche, building the new factory themselves.[3]

The Belle Fourche plant was profitable from 1927 to 1950, but lost money from 1951 to 1960. Management made aggressive plans to try to save the company. In 1962, farmers expanded east of the Missouri River, gaining 9,800 acres (40 km2). The yelds were disappointing, and the sugar content was low. At this time, research into the cost-benefit of leaving the factory was on the table. In 1964, the company retracted significantly and still lost money- $350,000. Ultimately, the factory didn't look good financially. The factory closed and was dismantled in 1965.[3]

Blight-resistant beets

Since most sugar beet seed came from Europe, the Americans asked their suppliers to develop blight-resistant beet lines. Blight was not a problem in Europe, so there was little enthusiasm. In addition, the suppliers didn't believe a resistant variety could be produced. The Spreckels Sugar Company of Spreckels, California began experimenting with blight-resistant plants in 1919, but did not develop a commercial variety by 1928.[22]

The U.S. Department of Agriculture developed a sugar beet variety in the late 1928s, known as "U.S. No. 1." Using a newly discovered overwintering technique for growing sugar beets for seed by the USDA and the New Mexico Agricultural Experiment Station, seed production plots were grown in 1930 in New Mexico, Hemet, California, and St. George, Utah.[22] Very limited quantities of this seed were available for the 1931 growing season- only 5 acres (20,000 m2) were grown in Washington County, Utah. Larger volume of seed were available for the 1934 season, and it was in heavy use by 1935. Other varieties were developed (12, 33, and 34) and in use by 1937.[22] These were significantly higher in sugar content, less likely to bolt (go to seed due to planting early), and more resistant to blight.[3][22]

By 1935, U-I was planting 650 acres (2.6 km2) of beets for seed in St. George and Moapa, Nevada, with an additional 150 acres (0.61 km2) in Hemet, California and 80 acres (320,000 m2) in Victorville, California. They produced 2,000,000 pounds (910,000 kg) of seed in 1936.[3]

For beet seed producers, yields drastically increased at the same time that labor requirements dropped. In 1932, a seed farm could expect to yield 2000 pounds of seed per acre. By the 1960s, yields were 3300 pounds per acre, an increase of 60.6%.[3]

New Washington factories

By the 1960s, seven factories had been built in Washington. Six were built by Utah-Idaho, and the seventh was purchased by U-I.[14]

Yakima Valley

U-I was lacking a factory in the Yakima Valley region of Washington after closing their Toppenish plant. The blight-resistant harvests were successful in 1935 despite large leafhopper infestation, and the farmers who were still planting beets would send them by rail to the Bellingham plant, a distance of 230 miles (370 km). A factory was rebuilt in October 1937, cannibalizing equipment from other factories, including at Moroni, Honeyville, and Lehi. The plant had a capacity of 1800 tons, which was increased to 3775 tons by the 1960s. The 1937 season resulted in the processing of 85,000 tons of beets. By the 1960s, the factory had contracts with 600 farmers, giving it 650,000 tons of sugar beets, with a yield of 23 tons per acre. The factory output was 65,000 tons of sugar.[3]

Moses Lake

U-I grew a test crop in Moses Lake, Washington in 1948, anticipating the completion of the Grand Coulee Dam and irrigation project. 1950 yields were 24 tons per acre from 1,120 acres (4.5 km2), and by 1951 it was 29 tons per acre from 1,700 acres (6.9 km2). The irrigation was available by 1952, so 3,400 acres (14 km2) were contracted in Moses Lake, Othello, Warden, and Quincy. Since the Toppenish factory was already operating at full capacity, the sugar beets were shipped to the Lincoln factory near Idaho Falls, Idaho, a distance of over 600 miles (970 km).[3]

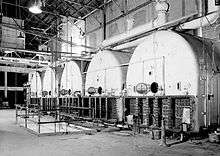

The decision to build a factory in Moses Lake was made in 1952. Equipment from the shuttered Chinook, Montana factory was reused in this plant, as well as equipment from the closed factories in Spanish Fork (formerly Nampa), Blackfoot, and Shelley. $8.1 million was required to get the factory running, and it was dedicated October 23, 1953, in time for the 1953 harvest. When it opened, it was the largest sugar beet processing factory in the United States.[23] The factory was processing 2000 tons per day during the first year. Later upgrades brought the Moses Lake factory to 6250 tons by the 1960s, and the total investment is approximately $20 million. By the 1960s, the factory had contracts with 800 farmers on 33,000 acres (130 km2), giving it 800,000 tons of sugar beets, with a yield of 24 tons per acre. A record was achieved in 1963 when this region averaged a 27.2 tons per acre yield.[3]

There was a serious explosion on September 25, 1963, likely caused by a dust explosion in one of seven silos, which were 108 ft (33 m) tall.[24][25][26][27][28][23][29][14][30] Seven died, another seven were injured, and the factory sustained $5 million in damage.[14][23] The factory was shuttered for over three weeks, causing over 2,000 acres (8.1 km2) to lay in fields.[27][28][29]

The Moses Lake plant was further expanded in the early 1970s increasing its beet slicing capacity to 11,000 tons/day making it the largest sugarbeet factory in the western hemisphere and the second largest in the world at the time. The Moses Lake facility also made use of stabilized stored "thick juice" and was able to produce sugar year round as a result. The Moses Lake plant was closed in 1979.[23]

Seed research

By the 1940s, progress was being made toward mechanically separating multigerm seed into segmented seed, allowing a reduction in labor-intensive agricultural thinning.[3] Research was being made toward a true monogerm seed by Russian refugees Viacheslav F. Savitsky, Helen Kharetchko Savitsky, and Utah native Forrest Vern Owen.[3][31] U-I and other sugar companies created the Beet Sugar Development Foundation, with a laboratory in West Jordan.[3] Together with the USDA's Division of Sugar Plant Investigations, they financed a search for naturally occurring monogerm seeds.[3] Two such plants were found, both in Oregon.[3][31] These were named SLC Monogerm 101 and SLC Monogerm 107.[3][31] The first commercial monogerm sugar beet resistant to the Curly Top blight was launched in 1955 by U-I, and by 1958 it was in large-scale production.[3]

Mechanization

| Years | Hours of labor |

|---|---|

| 1913–1917 | 11.2 |

| 1933–1936 | 8.7 |

| 1948 | 5.9 |

| 1958 | 4.4 |

| 1964 | 2.7 |

Partially in response to the labor shortages experienced during World War II, large efforts were made to mechanize the thinning, harvesting, and processing of sugar beets. Mechanical cross-blocking thinners were used starting in 1941, precision seed planting equipment was used starting in 1944, and more efficient mechanized harvesters were used starting in 1943, based on a "variable-cut topping mechanism" developed by J. B. Powers at the California Experiment Station of University of California, Davis, which was shared with manufacturers in a public domain manner. In 1946, 12% of the crop was harvested mechanically; by 1950, approximately 66% was mechanically harvested. This mechanization helped U-I stay productive compared to imported sugar. In 1960, U-I produced 325,000 tons of sugar.[3]

Legacy and divestment of sugar beet division

The Layton, Utah plant was closed in 1959, and then sold in 1965 or 1966.[3] Two other factories were sold or dismantled in 1965 or 1966: Gunnison, Utah, and Belle Fourche, South Dakota.[3] In 1963, the LDS church owned 48% of the stock.[32] A 1963 article in Barron's said "In the early years of Utah-Idaho, church ownership hampered the kind of hard dealing necessary in the trade. Today, however, such considerations are inconsequential."[32]

In the 1960s, U-I had five factories, down from the 28 they had built. They also owned a lime quarry west of Victor, Idaho, used as quicklime for the Lincoln, Idaho factory in processing beets.[3]

Utah-Idaho and its competitors (including the Amalgamated Sugar Company) were again sued beginning in 1971, alleging price fixing and market manipulation.[4] One such class action lawsuit was settled out of court in 1980.[33][34][35]

Utah-Idaho Sugar Company changed its name to simply "U and I" in 1975.[36] By this time, Utah-Idaho had moved into potato production. It put its four remaining sugar factories for sale in November 1978, stopped offering contracts to sugar beet growers, and closed the Moses Lake, Washington and Gunnison, Utah plants in 1979, entirely abandoning the sugar industry.[2][4][23][37] In the mid-1980s, the LDS church sold the company, and it was renamed AgraWest.[4] AgraWest was purchased by Idaho Pacific Corporation of Ririe, Idaho in 2000.[38]

U&I Sugar Corporation

The corporation is now (2011) concentrated on Brazilian sugar owning mills in Brazil and cane fields. U&I has purchased 2 logistic companies based in Sao Paulo and a sales marketing company in the United Kingdom formally Commodity Brokers Europe Ltd. Mike Crump the president of U&I Sugar Corporation now controls the process from growing to end buyer sales and is continuing to purchase mills in Brazil. The company now concentrates on selling cane sugar to the end buyer and does not trade on international market platforms thereby ensuring the best possible price for each mt produced.

In 2010 U&I moved into direct sales and the expansion program was initiated at www.uandisugar.com.

See also

- History of sugar

- Brigham Smoot: an executive of the company

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wiley, Harvey Washington Wiley; James Wilson; Charles F. Saylor (1898-03-02). "Special Report on the Beet-Sugar Industry in the United States". Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Agriculture. OCLC 17577464.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Burton, Robert A.; Paul Alan Cox (1998). "Sugarbeet Culture and Mormon Economic Development in the Intermountain West". Economic Botany. New York: New York Botanical Garden Press. 52 (2): 201–206. doi:10.1007/bf02861211. OCLC 1567380. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 Arrington, Leonard J. (1966). Beet sugar in the West; a history of the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company, 1891–1966. University of Washington Press. OCLC 234150.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 Godfrey, Matthew C. (2007). Religion, Politics, and Sugar: The Mormon Church, the Federal Government, and the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company, 1907–1921. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87421-658-5. OCLC 74988178.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Godfrey, Matthew C. (2001). "The Utah-Idaho Sugar Company: Political and Legal Troubles in the Aftermath of the First World War". Agricultural History. Agricultural History Society. 75 (2): 188–216. doi:10.1525/ah.2001.75.2.188. JSTOR 3744749.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Arrington, Leonard J (1966). "Utah's pioneer sugar beet plant; the Lehi factory of the Utah Sugar Company". Utah Historical Quarterly. Utah State Historical Society. 34 (2): 95–120. OCLC 1713705.

- 1 2 3 Taylor, Fred G. (1944). A Saga of Sugar. OCLC 1041958.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Eichner, Alfred S. (1969). The Emergence of Oligopoly; Sugar Refining as a Case Study. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-0-8018-1068-8. OCLC 50155.

- 1 2 Harris, Franklin Stewart (1919). The Sugar-Beet in America. The Rural Science Series. Macmillan Publishers. OCLC 1572747. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arrington, Leonard J. (1994), "The Sugar Industry in Utah", in Powell, Allan Kent, Utah History Encyclopedia, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, ISBN 0874804256, OCLC 30473917

- ↑ Deseret Evening News, October 22, 1900

- 1 2 3 4 5 Van Wagoner, Richard S. (1991). "The Lehi Sugar Factory—100 Years in Retrospect". Utah Historical Quarterly. Utah Historical Society. pp. 189–204.

- ↑ "The Sugar Bounty Bill". The Deseret News. 1903-02-13. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Arrington, Leonard J. (1966). "The U and I Sugar Company in Washington". Pacific Northwest Quarterly. Seattle, Washington: Washington State Historical Society. 57 (3): 101–109. OCLC 2392232.

- 1 2 3 4 Bachman, J. R. (1962). Story of the Amalgamated Sugar Company, 1897–1961. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers. OCLC 18047844.

- ↑ "Big sugar seizure made by government". The New York Times. 1919-12-07. pp. E1.

- ↑ Gates, Susa Young. "Susa Young Gates to Mrs. Jane Rockwell". Relief Society Magazine 7.

- ↑ "Grant Makes Appeal for Charity of Judgement; Plea Against Ill Will Theme of Conference". The Salt Lake Tribune. 1920-10-09.

- ↑ "Record First Session Crowd in Attendance". The Deseret News. 1920-10-08.

- ↑ Nibley to Smoot, December 3, 1920, Smoot Papers, box 42, folder 1. Quoted in Godfrey pg.152

- ↑ Federal Trade Commission Decisions, 404, 417

- 1 2 3 4 Coons, George Herbert (1936). "Improvement of the sugar beet". Division of Sugar Plant Investigations, Bureau of Plant Industry, U.S. Department of Agriculture: 625–656. OCLC 83102582.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Seven workers are killed in a Moses Lake sugar beet factory blast on September 25, 1963.". Washington State Department of Archeology and Historic Preservation. HistoryLink. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- ↑ "Sugar Beet Growers Look for New Outlet". Ellensburg Daily Record. 1963-09-26. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- ↑ "Workmen Recover 5th Body". Tri-City Herald. 1963-09-27. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- ↑ "Work Date Near at Sugar Factory". The Spokesman-Review. 1963-10-05. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- 1 2 "U&I Plant Will Reopen Oct. 11". Ellensburg Daily Record. 1963-10-04. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- 1 2 "Blast May Cost Beet Men Money". Tri-City Herald. 1963-10-02. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- 1 2 "Refinery Sets Start On Oct. 12". Tri-City Herald. 1963-10-01. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- ↑ "Check Digging On 2,000 Acres Of Sugar Beets". Ellensburg Daily Record. 1963-09-27. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- 1 2 3 Savitsky, Viacheslav F. (1950). "Monogerm Sugar Beets in the United States" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Society of Sugar Beet Technologists: 168–171. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- 1 2 "Strong Markets, Bigger Facilities Boost Net for Utah-Idaho Sugar". Barron's. 1963-10-21. pp. 30, 32.

- ↑ "Coupons part of sugar suit settlement". Anchorage Daily News. 1980-06-09.

- ↑ "Class Action Eyed in Sugar Suit". The Deseret News. 1972-12-21. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ↑ "4 sugar refiners sued by Oregon; The Antitrust Suit Alleges Price-Fixing". The New York Times. 1975-06-04.

- ↑ "U and I inc. melds sugar operations". Tri City Herald. 1977-09-07. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ↑ Blaine, Charley (1978-12-13). "Beef(sic) farmers face decline in acreage (Idaho Statesman)". The Register-Guard. Retrieved 2010-01-14.

- ↑ "Who are Idaho Pacific and AgraWest Foods?". Retrieved 2010-01-31.

External links

-

Media related to Utah-Idaho Sugar Company at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Utah-Idaho Sugar Company at Wikimedia Commons - Walter L. Webb Papers, MSS 361; 20th century Western & Mormon Manuscripts collection; L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. (Gives detailed account of the organization and history of the Utah Sugar Company.)