Visitor pattern

In object-oriented programming and software engineering, the visitor design pattern is a way of separating an algorithm from an object structure on which it operates. A practical result of this separation is the ability to add new operations to existing object structures without modifying those structures. It is one way to follow the open/closed principle.

In essence, the visitor allows one to add new virtual functions to a family of classes without modifying the classes themselves; instead, one creates a visitor class that implements all of the appropriate specializations of the virtual function. The visitor takes the instance reference as input, and implements the goal through double dispatch.

Definition

The Gang of Four defines the Visitor as:

Represent an operation to be performed on elements of an object structure. Visitor lets you define a new operation without changing the classes of the elements on which it operates.

The nature of the Visitor makes it an ideal pattern to plug into public APIs thus allowing its clients to perform operations on a class using a “visiting” class without having to modify the source.[1]

Motivation

Consider the design of a 2D CAD system. At its core there are several types to represent basic geometric shapes like circles, lines and arcs. The entities are ordered into layers, and at the top of the type hierarchy is the drawing, which is simply a list of layers, plus some additional properties.

A fundamental operation on this type hierarchy is saving the drawing to the system's native file format. At first glance it may seem acceptable to add local save methods to all types in the hierarchy. But then we also want to be able to save drawings to other file formats, and adding more and more methods for saving into lots of different file formats soon clutters the relatively pure geometric data structure we started out with.

A naive way to solve this would be to maintain separate functions for each file format. Such a save function would take a drawing as input, traverse it and encode into that specific file format. But if you do this for several different formats, you soon begin to see lots of duplication between the functions. For example, saving a circle shape in a raster format requires very similar code no matter what specific raster form is used, and is different from other primitive shapes; the case for other primitive shapes like lines and polygons is similar. The code therefore becomes a large outer loop traversing through the objects, with a large decision tree inside the loop querying the type of the object. Another problem with this approach is that it is very easy to miss a shape in one or more savers, or a new primitive shape is introduced but the save routine is implemented only for one file type and not others, leading to code extension and maintenance problems.

Instead, one could apply the Visitor pattern. The Visitor pattern encodes a logical operation on the whole hierarchy into a single class containing one method per type. In our CAD example, each save function would be implemented as a separate Visitor subclass. This would remove all duplication of type checks and traversal steps. It would also make the compiler complain if a shape is omitted.

Another motivation is to reuse iteration code. For example, iterating over a directory structure could be implemented with a visitor pattern. This would allow you to create file searches, file backups, directory removal, etc. by implementing a visitor for each function while reusing the iteration code.

Details

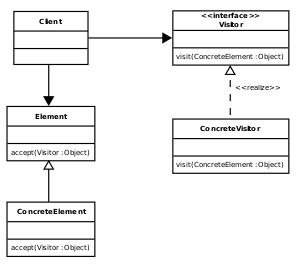

The visitor pattern requires a programming language that supports single dispatch. Under this condition, consider two objects, each of some class type; one is called the "element", and the other is called the "visitor". An element has an accept method that can take the visitor as an argument. The accept method calls a visit method of the visitor; the element passes itself as an argument to the visit method. Thus:

- When the

acceptmethod is called in the program, its implementation is chosen based on both:

- The dynamic type of the element.

- The static type of the visitor.

- When the associated

visitmethod is called, its implementation is chosen based on both:

- The dynamic type of the visitor.

- The static type of the element as known from within the implementation of the

acceptmethod, which is the same as the dynamic type of the element. (As a bonus, if the visitor can't handle an argument of the given element's type, then the compiler will catch the error.)

- Consequently, the implementation of the

visitmethod is chosen based on both:

- The dynamic type of the element.

- The dynamic type of the visitor.

- This effectively implements double dispatch; indeed, because the Common Lisp language's object system supports multiple dispatch (not just single dispatch), implementing the visitor pattern in Common Lisp is trivial.

In this way, a single algorithm can be written for traversing a graph of elements, and many different kinds of operations can be performed during that traversal by supplying different kinds of visitors to interact with the elements based on the dynamic types of both the elements and the visitors.

Some programming languages (e.g., C# via the Dynamic Language Runtime) support the notion of Multiple dispatch, which greatly simplifies the implementation of the Visitor pattern (a.k.a. Dynamic Visitor) by allowing the use of simple function overloading to cover all the cases being visited. A dynamic visitor, provided it operates on public data only, conforms to the Open/closed principle (since it does not modify existing structures) as well as the Single responsibility principle (since it implements the Visitor pattern in a separate component).

C++ example

Sources

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

class AbstractDispatcher; // Forward declare AbstractDispatcher

class File { // Parent class for the elements (ArchivedFile, SplitFile and ExtractedFile)

public:

// This function accepts an object of any class derived from AbstractDispatcher and must be implemented in all derived classes

virtual void accept(AbstractDispatcher &dispatcher) = 0;

};

// Forward declare specific elements (files) to be dispatched

class ArchivedFile;

class SplitFile;

class ExtractedFile;

class AbstractDispatcher { // Declares the interface for the dispatcher

public:

// Declare overloads for each kind of a file to dispatch

virtual void dispatch(ArchivedFile &file) = 0;

virtual void dispatch(SplitFile &file) = 0;

virtual void dispatch(ExtractedFile &file) = 0;

};

class ArchivedFile: public File { // Specific element class #1

public:

// Resolved at runtime, it calls the dispatcher's overloaded function, corresponding to ArchivedFile.

void accept(AbstractDispatcher &dispatcher) override {

dispatcher.dispatch(*this);

}

};

class SplitFile: public File { // Specific element class #2

public:

// Resolved at runtime, it calls the dispatcher's overloaded function, corresponding to SplitFile.

void accept(AbstractDispatcher &dispatcher) override {

dispatcher.dispatch(*this);

}

};

class ExtractedFile: public File { // Specific element class #3

public:

// Resolved at runtime, it calls the dispatcher's overloaded function, corresponding to ExtractedFile.

void accept(AbstractDispatcher &dispatcher) override {

dispatcher.dispatch(*this);

}

};

class Dispatcher: public AbstractDispatcher { // Implements dispatching of all kind of elements (files)

public:

void dispatch(ArchivedFile &file) override {

std::cout << "dispatching ArchivedFile" << std::endl;

}

void dispatch(SplitFile &file) override {

std::cout << "dispatching SplitFile" << std::endl;

}

void dispatch(ExtractedFile &file) override {

std::cout << "dispatching ExtractedFile" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

ArchivedFile archivedFile;

SplitFile splitFile;

ExtractedFile extractedFile;

std::vector<File*> files;

files.push_back(&archivedFile);

files.push_back(&splitFile);

files.push_back(&extractedFile);

Dispatcher dispatcher;

for (File* file : files) {

file->accept(dispatcher);

}

}

Output

dispatching ArchivedFile dispatching SplitFile dispatching ExtractedFile

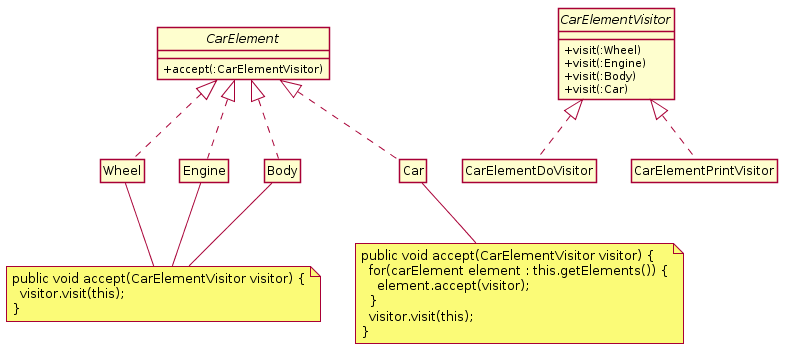

Java example

The following example is in the Java programming language, and shows how the contents of a tree of nodes (in this case describing the components of a car) can be printed. Instead of creating "print" methods for each node subclass (Wheel, Engine, Body, and Car), a single visitor class (CarElementPrintVisitor) performs the required printing action. Because different node subclasses require slightly different actions to print properly, CarElementPrintVisitor dispatches actions based on the class of the argument passed to its visit method. CarElementDoVisitor, which is analogous to a save operation for a different file format, does likewise.

Diagram

Sources

interface CarElementVisitor {

void visit(Wheel wheel);

void visit(Engine engine);

void visit(Body body);

void visit(Car car);

}

interface CarElement {

void accept(CarElementVisitor visitor);

}

class Wheel implements CarElement {

private String name;

public Wheel(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public String getName() {

return this.name;

}

public void accept(CarElementVisitor visitor) {

/*

* accept(CarElementVisitor) in Wheel implements

* accept(CarElementVisitor) in CarElement, so the call

* to accept is bound at run time. This can be considered

* the first dispatch. However, the decision to call

* visit(Wheel) (as opposed to visit(Engine) etc.) can be

* made during compile time since 'this' is known at compile

* time to be a Wheel. Moreover, each implementation of

* CarElementVisitor implements the visit(Wheel), which is

* another decision that is made at run time. This can be

* considered the second dispatch.

*/

visitor.visit(this);

}

}

class Engine implements CarElement {

public void accept(CarElementVisitor visitor) {

visitor.visit(this);

}

}

class Body implements CarElement {

public void accept(CarElementVisitor visitor) {

visitor.visit(this);

}

}

class Car implements CarElement {

CarElement[] elements;

public Car() {

this.elements = new CarElement[] { new Wheel("front left"),

new Wheel("front right"), new Wheel("back left"),

new Wheel("back right"), new Body(), new Engine() };

}

public void accept(CarElementVisitor visitor) {

for(CarElement elem : elements) {

elem.accept(visitor);

}

visitor.visit(this);

}

}

class CarElementPrintVisitor implements CarElementVisitor {

public void visit(Wheel wheel) {

System.out.println("Visiting " + wheel.getName() + " wheel");

}

public void visit(Engine engine) {

System.out.println("Visiting engine");

}

public void visit(Body body) {

System.out.println("Visiting body");

}

public void visit(Car car) {

System.out.println("Visiting car");

}

}

class CarElementDoVisitor implements CarElementVisitor {

public void visit(Wheel wheel) {

System.out.println("Kicking my " + wheel.getName() + " wheel");

}

public void visit(Engine engine) {

System.out.println("Starting my engine");

}

public void visit(Body body) {

System.out.println("Moving my body");

}

public void visit(Car car) {

System.out.println("Starting my car");

}

}

public class VisitorDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

CarElement car = new Car();

car.accept(new CarElementPrintVisitor());

car.accept(new CarElementDoVisitor());

}

}

Note: A more flexible approach to this pattern is to create a wrapper class implementing the interface defining the accept method. The wrapper contains a reference pointing to the CarElement which could be initialized through the constructor. This approach avoids having to implement an interface on each element. See article Java Tip 98 article below

Output

Visiting front left wheel Visiting front right wheel Visiting back left wheel Visiting back right wheel Visiting body Visiting engine Visiting car Kicking my front left wheel Kicking my front right wheel Kicking my back left wheel Kicking my back right wheel Moving my body Starting my engine Starting my car

Common Lisp Example

Sources

(defclass auto ()

((elements :initarg :elements)))

(defclass auto-part ()

((name :initarg :name :initform "<unnamed-car-part>")))

(defmethod print-object ((p auto-part) stream)

(print-object (slot-value p 'name) stream))

(defclass wheel (auto-part) ())

(defclass body (auto-part) ())

(defclass engine (auto-part) ())

(defgeneric traverse (function object other-object))

(defmethod traverse (function (a auto) other-object)

(with-slots (elements) a

(dolist (e elements)

(funcall function e other-object))))

;; do-something visitations

;; catch all

(defmethod do-something (object other-object)

(format t "don't know how ~s and ~s should interact~%" object other-object))

;; visitation involving wheel and integer

(defmethod do-something ((object wheel) (other-object integer))

(format t "kicking wheel ~s ~s times~%" object other-object))

;; visitation involving wheel and symbol

(defmethod do-something ((object wheel) (other-object symbol))

(format t "kicking wheel ~s symbolically using symbol ~s~%" object other-object))

(defmethod do-something ((object engine) (other-object integer))

(format t "starting engine ~s ~s times~%" object other-object))

(defmethod do-something ((object engine) (other-object symbol))

(format t "starting engine ~s symbolically using symbol ~s~%" object other-object))

(let ((a (make-instance 'auto

:elements `(,(make-instance 'wheel :name "front-left-wheel")

,(make-instance 'wheel :name "front-right-wheel")

,(make-instance 'wheel :name "rear-left-wheel")

,(make-instance 'wheel :name "rear-right-wheel")

,(make-instance 'body :name "body")

,(make-instance 'engine :name "engine")))))

;; traverse to print elements

;; stream *standard-output* plays the role of other-object here

(traverse #'print a *standard-output*)

(terpri) ;; print newline

;; traverse with arbitrary context from other object

(traverse #'do-something a 42)

;; traverse with arbitrary context from other object

(traverse #'do-something a 'abc))

Output

"front-left-wheel" "front-right-wheel" "rear-right-wheel" "rear-right-wheel" "body" "engine" kicking wheel "front-left-wheel" 42 times kicking wheel "front-right-wheel" 42 times kicking wheel "rear-right-wheel" 42 times kicking wheel "rear-right-wheel" 42 times don't know how "body" and 42 should interact starting engine "engine" 42 times kicking wheel "front-left-wheel" symbolically using symbol ABC kicking wheel "front-right-wheel" symbolically using symbol ABC kicking wheel "rear-right-wheel" symbolically using symbol ABC kicking wheel "rear-right-wheel" symbolically using symbol ABC don't know how "body" and ABC should interact starting engine "engine" symbolically using symbol ABC

Notes

The other-object parameter is superfluous in traverse. The reason is that it is possible to use an anonymous function which calls the desired target method with a lexically captured object:

(defmethod traverse (function (a auto)) ;; other-object removed

(with-slots (elements) a

(dolist (e elements)

(funcall function e)))) ;; from here too

;; ...

;; alternative way to print-traverse

(traverse (lambda (o) (print o *standard-output*)) a)

;; alternative way to do-something with

;; elements of a and integer 42

(traverse (lambda (o) (do-something o 42)) a)

Now, the multiple dispatch occurs in the call issued from the body of the anonymous function, and so traverse is just a mapping function which distributes a function application over the elements of an object. Thus all traces of the Visitor Pattern disappear, except for the mapping function, in which there is no evidence of two objects being involved. All knowledge of there being two objects and a dispatch on their types is in the lambda function.

Related design patterns

- Command pattern: It encapsulates like the visitor pattern one or more functions in an object to present them to a caller. Unlike the visitor, the command pattern does not enclose a principle to traverse the object structure.

- Iterator pattern: This pattern defines a traversal principle like the visitor pattern without making a type differentiation within the traversed objects.

See also

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Visitor pattern. |

| The Wikibook Computer Science Design Patterns has a page on the topic of: Visitor implementations in various languages |

- The Visitor Family of Design Patterns - a rough chapter from The Principles, Patterns, and Practices of Agile Software Development, Robert C. Martin, Prentice Hall

- Visitor pattern in UML and in LePUS3 (a Design Description Language)

- Article "Componentization: the Visitor Example by Bertrand Meyer and Karine Arnout, Computer (IEEE), vol. 39, no. 7, July 2006, pages 23-30.

- Article A Type-theoretic Reconstruction of the Visitor Pattern

- Article "The Essence of the Visitor Pattern" by Jens Palsberg and C. Barry Jay. 1997 IEEE-CS COMPSAC paper showing that accept() methods are unnecessary when reflection is available; introduces term 'Walkabout' for the technique.

- Article "A Time for Reflection" by Bruce Wallace - subtitled "Java 1.2's reflection capabilities eliminate burdensome accept() methods from your Visitor pattern"

- Visitor Patterns as a universal model of terminating computation.

- Visitor Pattern using reflection(java).

- PerfectJPattern Open Source Project, Provides a context-free and type-safe implementation of the Visitor Pattern in Java based on Delegates.

- Visitor Design Pattern

- Visitor C++11 implementation example

- Article Java Tip 98: Reflect on the Visitor design pattern