Ahwahnee Hotel

|

The Ahwahnee | |

|

The Ahwahnee Hotel in winter | |

| |

| Location | Yosemite National Park, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°44′44.68″N 119°34′27.07″W / 37.7457444°N 119.5741861°WCoordinates: 37°44′44.68″N 119°34′27.07″W / 37.7457444°N 119.5741861°W |

| Built | August 1, 1926–July 1927 |

| Architect | Gilbert Stanley Underwood |

| Architectural style | National Park Service Rustic |

| NRHP Reference # | 77000149 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | February 15, 1977[1] |

| Designated NHL | May 28, 1987[2] |

The Ahwahnee Hotel is a grand hotel[3] in Yosemite National Park, California, on the floor of Yosemite Valley, constructed from steel, stone, concrete, wood and glass, which opened in 1927. It is a premiere example of National Park Service rustic architecture and was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1987.[2][4] The hotel was built by two companies that were merged when the National Park Service began leasing concessions to a single concessionaire in 1925. The Curry Company, owned by David and Jennie Curry and the Yosemite Park Company, the owners of the Yosemite Lodge, became the new "Yosemite Park & Curry Company" headed by Donald Tressider. The structure originally served as both a luxury hotel and the company offices of YPC&CC. Despite financial struggles, the YPC&CC remained the concessioner for the Ahwahnee Hotel until 1993, before the National Park Service required a new concessioner to buy the YPC&CC, creating a new company and the current concessioner, Delaware North.

The Ahwahnee was renamed the Majestic Yosemite Hotel on March 1, 2016, due to a legal dispute between the US Government, which owns the property, and the outgoing concessionaire, Delaware North, which claims rights to the trademarked name.[5]

Background and history

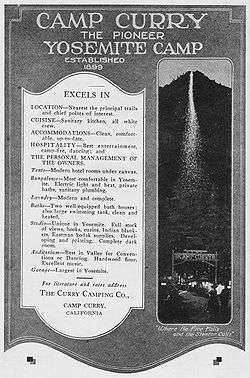

The Currys

David and Jennie Curry, owners and operators of Curry Village, were schoolteachers who arrived in Yosemite Valley in 1899.[6] The couple offset some of their vacation costs by giving camping tours, having experimented early on in Yellowstone National Park. For three summers in a row, the Currys led teachers on camping outings to Yellowstone with horse and wagon;[7] arriving in Yosemite with a cook and seven tents. Despite the two week, round trip travel period from Merced, California, the camp registered 292 guests its first year.[8] The couple brought their three children with them. Foster, Mary and Marjorie (ages four through eleven) all helped out where they were able.[7] The Curry Company came to dominate the politics of the park for decades. David wrote the Secretary of the Interior, Franklin Lane, in an effort extend the park's tourist season, hoping to expand his business.[6] The Currys were adept at promotion and revived an old tradition started by James McCauley on the Fourth of July 1872. At sunset, piles of burning logs were pushed off Glacier Point creating what was known as the Fire Fall.[9] The theory was, national parks were for recreational use.[10] David Curry died in 1917 and left the management of Camp Curry to his widow Jennie, now known as "Mother Curry". She received help from her children, particularly Mary and Mary's husband Donald Tresidder.[7]

In 1915, Stephen T. Mather convinced D.J. Desmond to convert an old army barracks into the Yosemite Lodge. Desmond also began a hotel at Glacier Point the following year, while buying out a number of businesses to improve Yosemite Park Company's position in upcoming park leasing contracts.[11] A congressional act allowed for efficient supervision of the parks for the enjoyment of the public.[12] Beginning in 1916, the newly formed National Park Service began a concerted effort to attract visitors to the parks and create better accommodations and services.[13] Under the direction of Mather, whose greatest desire was to build a luxury hotel in Yosemite, an attempt was made to build near Yosemite Falls, but funding failed.[14] Prominent socialite Lady Astor and other wealthy tourists had refused to stay at the park due to the horrible conditions of the facilities.[15] (Lady Astor is reported to have disliked the Sentinel Hotel, describing it as "primitive".[10]) In 1925, the Park Service, unhappy with the declining concessions situation within the parks, decided to grant a monopoly to single entities to run the hotel and food services in each park. Two existing companies, Curry Company (Curry Village tent camp) and The Yosemite Park Company (Yosemite Lodge), were merged to create one larger company to run all of the hotels and food concessions in Yosemite National Park. As part of this reorganization, the newly formed Yosemite Park and Curry Company (YPCCC) proposed a new luxury hotel.[16] The new head of the YPCCC became Donald Tresidder from the Curry Company. It was hoped that the more successful Curry Company involvement would help build Mather's hotel.[14] While the National Park Service had complete control, the YPCC Company began to have further influence. The monopoly obtained leasing privileges and accumulated both financial and political benefits.[17]

Yosemite Park & Curry Company

What started out as a simple campsite begun by two Indiana schoolteachers ended up as the sole concessionaire for the park. Yosemite Park & Curry Company went on to build much of the park's service structures over decades.[18] Donald Tresidder, as president of YPCCC, built the Ahwahnee and several other major structures within the park.[9] The name originally selected for the new hotel was "Yosemite All-Year-Round Hotel", but Tresidder changed it just prior to opening to reflect the site's native name.[10]

After the Ahwahnee was built, Tresidder had to overcome a number of financial obstacles. The cost of the hotel was nearly double the estimate, and as fall approached, guests began to decline. Park officials became concerned and suggested closing the hotel for the winter. To avoid this and keep guests and income flowing, Tresidder centered on skiing and other winter activities.[15] In order to keep the hotel filled throughout the holiday period, Tresidder also proposed Christmas entertainment. A banquet event was planned based on a story by Washington Irving about an eighteenth-century English Christmas at the home of the Squire of Bracebridge. The cast was filled with locals from the park, including photographer Ansel Adams.[19]

In 1993 the National Park Service required a new concessioner to purchase the Yosemite Park & Curry Company from MCA and rename the business as a new company. The new concession contract required assuming all the assets and liabilities of previous operator and to deed the real property to the National Park Service.[20]

Name change

In January 2016, it was announced that due to a trademark dispute with outgoing concessionaire Delaware North, the Ahwahnee Hotel, as well as other historic hotels and lodges in the park, would be renamed. The Ahwahnee was renamed the Majestic Yosemite Hotel effective March 1, 2016.[21][22]

In 2014, Delaware North lost a bid to renew its contract with the U.S. government to manage the property to Yosemite Hospitality, LLC, a division of Aramark.[23] When it had originally taken over the concessionaries in 1993, Delaware North was contractually required to purchase, at fair market value, "the assets of the previous concessionaire, including its intellectual property, at a cost of $115 million in today's dollars." This property includes trademarks that were registered by both Delaware North and its predecessors, including place names such as Ahwahnee, Badger Pass, Curry Village, Yosemite Lodge, the slogan "Go climb a rock", and even "Yosemite National Park" itself.[21][22] The contract with Delaware North also required that if it is succeeded as concessionaire, the new company must acquire all of the assets of the previous operator at fair market value. The contract with Yosemite Hospitality stated that the company be required to purchase furniture, equipment, vehicles, and "other property"—which did not explicitly include intellectual property.[24]

In 2015, Delaware North sued the NPS in the United States Court of Claims for breach of contract, claiming that the contract with Yosemite Hospitality excluded intellectual property from the asset purchasing clause, and demanded a payment for the property to be determined in court. Delaware North initially asserted the fair market value of its properties to be $51 million.[24] When it offered for bid the contract to operate these facilities, the National Park Service estimated the value of the intangible assets at $3.5 million.[24] Delaware North claimed to have offered to temporarily license the trademarks while the dispute is resolved, but claims that the government did not respond.[21][22]

The dispute gained national attention after it was publicized in an issue of Outside magazine, which led to the Sierra Club issuing a petition requesting that Delaware North drop the lawsuit.[21][22]

Concept and build

Architecture and interior design

The Ahwahnee hotel was designed by architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood (who also designed the Zion Lodge, Bryce Canyon Lodge, and Grand Canyon North Rim Lodge). It is considered a masterpiece of "parkitecture"[10] and is made to feel rustic and match its surroundings. Interior designers were Dr. Phyllis Ackerman and Professor Arthur Upham Pope.[25] The interior work was carried out by a number of artisans under their supervision. The individual border designs in the beams of the Great Lounge are by artist Jeanette Dryer Spencer.[26] The site for the hotel is below the Royal Arches rock formation in a meadow area that had served in the past as a village for the native Miwoks, who formerly lived in the valley, and a stables complex known as Kenneyville. The site was chosen for its views of many of the iconic sights in Yosemite, including Glacier Point, Half Dome, and Yosemite Falls, and its exposure to the sun allowing for natural heating.[27]

The original concept art of the hotel was far more megalithic in scale than what was built.[28] Underwood's original design concept called for a massive six story structure.[10] Tresidder and the board originally had requested a hotel with only 100 guest rooms that felt like a luxurious country home and not a hotel. The design was changed several times and at one point was to be no larger than three stories, with a wooden and stone construction. Plans then changed again, to a larger scale.[29] Interior designs and designers had also changed. The husband and wife team of Ackerman and Pope were chosen over artist/interior designer Henry Lovins from Los Angeles. Lovins' interior design renderings, provided by Elizabeth Lovins (Director of the Hollywood Art Center Archive), depict a "Mayan revival" drawing of Hispano-Moresque styling.[10] Historians, Ackerman and Pope created a style that mixed Art Deco, Native American, Middle Eastern, and Arts and Crafts.[30] A lot of decoration originally used was Persian. (Ackerman and Pope actually became consultants in Iran. Pope even has a mausoleum built for him by the Shah.)[31]

Eventually the Grand Dining Room was scaled back from seating for 1,000 to seating for only 350 guests.[29] The Ahwahnee is a 150,000 square feet (14,000 m2) Y-shaped building[25] and has 97 hotel rooms, parlors, and suites, each accented with original Native American designs. 24 cottages bring the total number of rooms to 121.[32]

Construction

The hotel was constructed from 5,000 tons (4,535 t) of rough-cut granite, 1,000 tons (907 t) of steel, and 30,000 feet (9,140 m) of timber.[27] The apparent wood siding and structural timber on the hotel's exterior are actually formed of stained concrete poured into molds to simulate a wood pattern.[25] The steel came from the Union Iron Works in San Francisco, and the timber from land owned by the Curry family.[14] Concrete was chosen as the material for the outside "wood" elements to add fire resistance to the hotel. The construction lasted eleven months and cost US$1,225,000 upon completion in July 1927.[27] After construction was complete the company began an advertising campaign to showcase the new amenities.[16]

Just before opening, the director noticed that the porte-cochere planned for the west side of the building, where the Indian room now sits, would allow exhaust fumes from automobiles to invade the premises. A hastily designed Douglas Fir pole porte-cochere entry and parking area were erected on the east side of the hotel to correct this. (The logs were replaced in the 1990s.) Almost immediately after opening, the next of many alterations were made to the hotel. In 1928, a roof garden and dance hall were converted into a private apartment after the dance hall failed to draw an audience. It was found that the load-bearing trusses in the dining room were barely adequate to support the snow load on the roof and potential earthquake stresses. This led to the trusses' being reinforced in 1931-32.[25]

When Prohibition was rescinded in 1933, a private dining room was converted into the El Dorado Diggins bar, evocative of the California Gold Rush period.[25] 1943 saw the United States Navy take over the hotel for use as a convalescent hospital for war veterans. Some of the changes made to the hotel by the Navy were repainting of the interior, conversion of chauffeur and maid rooms into guest rooms, and enclosure of the original porte-cochere.[25]

The 1950s, '60s, and '70s brought modernizations to the hotel, including fire escapes, a fire alarm system, smoke detectors, and a sprinkler system, along with an outdoor swimming pool and automatic elevators.[25] 2003-2004 saw a major roof overhaul, wherein virtually the entire slate-tile roof and copper gutter system were replaced. Martech Associates, Inc. of Millheim, Pennsylvania designed the updated roof and served as the general contractor for the project. The project cost approximately US$4 million and is especially notable for its 97 percent material recycling rate. An article in the Los Angeles Times on March 13, 2009, stated that seismic retrofits may be needed for the Ahwahnee.[33]

Grand Dining Room and kitchen

The kitchen area reflects the original design concept; it includes separate stations for baking and pastries and was never reduced when the original project was downsized.[26] High quality kitchen appliances were installed so the hotel could compete with fine dining establishments, and the facility was specifically constructed to handle special events and functions.[14] The wood beames in the dining room are actually hollow, with steel beams going through them for fire safety reasons. Every detail was carefully thought out. The alcove window at the end of the room perfectly framed Yosemite Falls when the hotel was completed.[14] The dining room is 130 feet long and 51 feet wide, with a 34-foot ceiling supported with rock columns creating a cathedral like atmosphere.[34] While the dress code for the park is usually very casual, the Ahwahnee Dining Room used to require a jacket for men, but it later relaxed that tradition. Now collared shirts for men are allowed and women may wear either a dress or slacks and a blouse.[35]

The regular entertainment provided at dinner is a pianist (dressed in a tuxedo if male). Local Yosemite artist, Dudley Kendall played piano in the dining room at the Ahwahnee for years and had his work displayed at the hotel.[36]

Bracebridge tradition

The Bracebridge Dinner is a seven-course formal gathering[37] presented as a feast given by a Renaissance-era lord. Started in 1927, the Ahwahnee's first year of operation, the dinner is inspired by the fictional Squire Bracebridge's Yule celebration in a story from The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. by Washington Irving. Music and theatrical performances based on Irving's story accompany the introduction of each course.[38] Donald Tresidder, then president of the Yosemite Park & Curry Company (which operated the Ahwahnee and all other concessions in the park), conceived the idea for the event with his wife Mary Curry, their friends, and park staff. It is held in the grand dining room at the hotel. Tresidder hired Garnet Holme the first year to write the script and produce the event.[39] Tresidder and his wife played the squire and his lady until Tresidder's death in 1948. Photographer Ansel Adams was earning a secure living from work for the YP&C Co during the Great Depression.[40] Adams was well known in Yosemite for his eccentricities and was asked to be a part of Donald Tresidder's new winter celebrations in the elaborate, theatrical Christmas dinner with friends from the nearby Bohemian Club. Cast as the "Jester", Adams had asked the director for suggestions but was told to just act like a jester. Adams fortified himself with a few drinks and went on to climb the granite pillars to the rafters.[40] Adams played the Lord of Misrule for the first two years. When Holme died in 1929, Tresidder asked Adams to take over the direction of the show. Adams reworked the script considerably in 1931, creating the role of Major Domo, head of the household, for himself while his wife, Virginia Best Adams, played the housekeeper.

The dinner was not held during World War II, when the Ahwahnee was functioning as a naval hospital. The 1946 dinner introduced chorale concerts and more significant musical performances. Ansel Adams retired from the event in 1973, passing it on to Eugene Fulton, who had been part of the male chorus since 1934 and musical director since 1946. Until 1956, there was only a single performance. The number of performances gradually increased to a total of eight. Fulton died unexpectedly on Christmas Eve in 1978. His wife, Anna-Marie, and his daughter, Andrea, took over that year and produced the show. In 1979, Andrea Fulton assumed the role of director, which she continues to this day while also playing the role of housekeeper.[41]

In 2011, the Bracebridge dinner celebrated its 85th anniversary.[42] Travel + Leisure magazine named Yosemite’s Ahwahnee Hotel as one of the best hotels in the United States for the holidays [43] for two consecutive years (2011 and 2012).[44] For much of its history, tickets to the event were difficult to obtain.[45] In prior years, the scarce tickets were awarded to applicants by lottery. In 1992, there were a reported 60,000 applications for the coveted 1,650 seats.[46] In 1995, the organizers of the traditional dinner accepted ticket cancellations because the park could have been shut down due to the national budget impasse.[47]

Great Lounge

The Great Lounge is one of the main public spaces in the hotel. The large space spans the full width of the wing and nearly its full length (minus the solarium). There are two large fireplaces on either end of the room made from cut sandstone. On either side of the lounge is a series of floor to ceiling plate glass, picture windows ornamented at their tops with stained glass.[48]

In popular culture

Film

Interiors of the Ahwahnee Hotel were adapted for Stanley Kubrick's horror film The Shining (1980). Designers at Elstree Studios incorporated the hotel's lobby, elevators, and Great Lounge into sets for the Overlook Hotel.

Both the film The Caine Mutiny (1954) and Color of a Brisk and Leaping Day (1996) include footage of the Ahwahnee hotel.

Notable guests

The hotel and dining room have hosted many notable figures including artists, royalty, heads of state, film and television stars, writers, business executives, and other celebrities.[34] Examples of notable guests include heads of state Queen Elizabeth II, Barack Obama, Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, and the Shah of Iran;[49] business moguls Walt Disney and Steve Jobs; entertainers Desi Arnaz, Lucille Ball, Charlie Chaplin, Judy Garland, Leonard Nimoy, Will Rogers and William Shatner; and writer Gertrude Stein.[49][50]

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Yosemite National Park

- Yosemite Valley

- Touron

- Donald Tresidder

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Mariposa County, California

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2006-03-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 "The Ahwahnee". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- ↑ J. C. Gacilo (2003). Postcards and Trains: Travel USA by Train. Trafford Publishing. pp. 152–. ISBN 978-1-4120-0257-8.

- ↑ Laura Soullière Harrison (1986). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: The Ahwahnee Hotel" (PDF). National Park Service. and Accompanying 34 photos, exterior and interior, from 1985. (7.25 MB)

- ↑ http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-yosemite-ahwahnee-hotel-20160114-story.html

- 1 2 George Wuerthner (1994). Yosemite: A Visitor's Companion. Stackpole Books. pp. 40–. ISBN 978-0-8117-2598-9.

- 1 2 3 Polly Welts Kaufman (2006). National Parks and the Woman's Voice: A History. UNM Press. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-0-8263-3994-2.

- ↑ Katherine Ames Taylor (1948). Yosemite Trails and Tales. Stanford University Press. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-8047-4098-2.

- 1 2 Peter Browning (2005). Yosemite Place Names: The Historic Background of Geographic Names in Yosemite National Park. Great West Books. pp. 154–. ISBN 978-0-944220-19-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Amy Scott (2006). Yosemite: Art of an American Icon. University of California Press. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-520-24922-6.

- ↑ Ethan Carr (2007). Mission 66: Modernism and the National Park Dilemma. Univ of Massachusetts Press. pp. 230–. ISBN 978-1-55849-587-6.

- ↑ James Earl Sherow (1998). A Sense of the American West: An Anthology of Environmental History. UNM Press. pp. 162–. ISBN 978-0-8263-1913-5.

- ↑ Lary M. Dilsaver; Craig E. Colten (1 January 1992). The American Environment: Interpretations of Past Geographies. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 238–. ISBN 978-0-8476-7754-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Leroy Radanovich (2004). Yosemite Valley. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 73–79. ISBN 978-0-7385-2877-9.

- 1 2 International Skiing History Association (March 2003). Skiing Heritage Journal. International Skiing History Association. pp. 21–. ISSN 1082-2895.

- 1 2 American Alpine Club (1 January 1998). The American Alpine Journal 1998. The Mountaineers Books. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-1-933056-45-6.

- ↑ Alfred Runte (1 January 1993). Yosemite: The Embattled Wilderness. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 145–. ISBN 978-0-8032-8941-3.

- ↑ William R. Lowry (2009). Repairing Paradise: The Restoration of Nature in America's National Parks. Brookings Institution Press. pp. 67–. ISBN 978-0-8157-0392-1.

- ↑ Mary Street Alinder (15 April 1998). Ansel Adams: A Biography. Macmillan. pp. 128–. ISBN 978-0-8050-5835-2.

- ↑ "Congressional Oversight Committee Hearings, Yosemite Concession Contract, March 24, 1993". archive.org. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Iconic names at Yosemite are subject of $51 million trademark battle". Boston Globe. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Therolf, Garrett. "Yosemite's famous Ahwahnee Hotel to change name in trademark dispute". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ↑ "Despite some locale renaming, "Yosemite National Park" trademark dispute persists". Ars Technica. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Delaware North sues park service over Yosemite dispute". The Buffalo News.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Harrison, Laura Soullière (February 26, 2001). "The Ahwahnee Hotel". Architecture in the Parks: A National Historic Landmark Theme Study. National Park Service - Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 16 July 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- 1 2 Alice Van Ommeren (2013). Yosemite's Historic Hotels and Camps. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-0-7385-9997-7.

- 1 2 3 "The Ahwahnee History". Yosemite National Park. Delaware North Companies Parks & Resorts at Yosemite, Inc. 2003. Archived from the original on 15 March 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- ↑ Tweed, Soulliere, Law, William, Laura, Henry (February 1977). "Rustic Architecture:". Division of Culutral Resource Management. National Park Service. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- 1 2 National Park Service (U S ). A Sense of Place: Design Guidelines for Yosemite National Park. Government Printing Office. pp. 142–. ISBN 978-0-16-090412-7.

- ↑ Anthony Pioppi; Chris Gonsalves (14 April 2009). Haunted Golf: Spirited Tales from the Rough. Globe Pequot. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-1-59921-747-5.

- ↑ Snow Country. February 1990. pp. 44–. ISSN 0896-758X.

- ↑ "The Ahwahnee". Yosemite National Park. Delaware North Companies Parks & Resorts at Yosemite, Inc. 2003. Archived from the original on 3 July 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- ↑ "Yosemite's Ahwahnee Hotel fails quake safety standards - Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times. 13 March 2009.

- 1 2 Ski. November 1985. pp. 181–. ISSN 0037-6159.

- ↑ Karen Misuraca; Maxine Cass (1 May 2006). Insiders' Guide to Yosemite. Globe Pequot Press. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-7627-4050-5.

- ↑ Hugh Maguire (March 2012). My First 40 Jobs: A Memoir. iUniverse. pp. 154–. ISBN 978-1-4759-0137-5.

- ↑ "Get ready for Bracebridge, Yosemite's famous Christmas feast". Los Angeles Times. October 17, 2012.

- ↑ "Christmas is magical at a National Park lodge". NBC News. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ "Christmas Dinner: A Grand Scale". Sierra News Online. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- 1 2 Jonathan Spaulding (1998). Ansel Adams and the American Landscape: A Biography. University of California Press. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-0-520-21663-1.

- ↑ Shirley Sargent (1990). The First 100 Years: Yosemite 1890-1990. Penguin Group USA. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-399-51603-0.

- ↑ Gardener, Terry (December 21, 2011). "It's the 85th Anniversary of Yosemite's Bracebridge Dinner". Huffington Post.

- ↑ "Yosemite's Ahwahnee among the Best U.S. Hotels for the Holidays". Delaware North. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ "Best US Hotels for the Holidays". Travel & Leisure. 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ "Bracebridge Dinner is a magical feast full of pageantry". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ "It's time to plan Christmas dinner next year's". Baltimore Sun. 1992. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- ↑ Brazil, Eric (December 18, 1995). "Yosemite's Christmas dinners may be canceled". SFGate.com.

- ↑ Lewis Kemper (18 March 2010). Photographing Yosemite Digital Field Guide. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-470-87902-3.

- 1 2 "History of The Ahwahnee Hotel, Yosemite National Park, California". Historic-hotels-lodges.com. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

- ↑ James Kaiser (May 2007). Yosemite: Yosemite National Park. James Kaiser. pp. 162–. ISBN 978-0-9678904-7-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ahwahnee Hotel. |

- "The Official site for The Ahwahnee hotel". DNC Parks & Resorts at Yosemite - the National Park concessioner. 2008. Archived from the original on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- Architecture in the Parks: A National Historic Landmark Theme Study: The Ahwahnee Hotel, by Laura Soullière Harrison, 1986, at National Park Service.

- "Dining Out: Ahwahnee Hotel Kitchen (Yosemite, California)". Cooking For Engineers. January 22, 2005. Archived from the original on 6 August 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- The Ahwahnee Hotel, Yosemite. Virtual photo tour, history, more. Lots of photos.

- National Historic Landmarks Program Official website

- A History of the NHL Program

- List of NHLs