Anthony Henday Drive

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highway 216 | ||||

| ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by Volker Stevin, Carmacks, Lafarge[lower-alpha 1] | ||||

| Length: | 77.23 km[1] (47.99 mi) | |||

| History: |

1990 (construction begins) 1992 (first segment open) 2016 (ring completed) | |||

| Component highways: |

(Unsigned: | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| Ring road around Edmonton | ||||

|

| ||||

| Location | ||||

| Specialized and rural municipalities: | Strathcona County | |||

| Major cities: | Edmonton, St. Albert, Sherwood Park | |||

| Highway system | ||||

|

Provincial highways in Alberta

| ||||

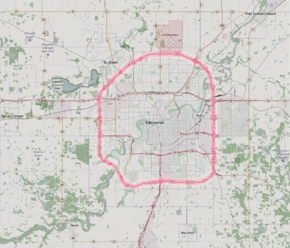

Anthony Henday Drive is a 77 km (48 mi) freeway that encircles Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Designated as Highway 216 over its entire length, it is a heavily travelled commuter and truck bypass route, with the southwest quadrant serving as a portion of the critical CANAMEX Corridor linking Canada to the United States and Mexico. Traffic levels quickly increased as sections of the freeway were completed; it is now one of the busiest in Western Canada carrying over 105,000 vehicles per day at its busiest point in west Edmonton. Calgary Trail/Gateway Boulevard is designated as the starting point of the loop, with exit numbers increasing clockwise across the North Saskatchewan River to the Cameron Heights neighbourhood, then north past Whitemud Drive, Stony Plain Road and Yellowhead Trail to St. Albert. It continues east past 97 Street to Manning Drive, then south across the North Saskatchewan River a second time. Entering Strathcona County, it again crosses Yellowhead Trail before passing Sherwood Park and Whitemud Drive. Continuing south to Highway 14, the road re-enters southeast Edmonton and turns west to complete the ring.

The freeway was named after 18th century explorer Anthony Henday, one of the first European men to explore central Alberta. Its designation of 216 is derived from its bypass linkages to Edmonton's two major crossroads, Highways 2 and 16. Anthony Henday Drive is the first free-flowing orbital road in Canada after construction finished in late 2016 at a total cost of approximately $4.3 billion over a period of 26 years. Planning of the ring began in the 1950s, followed by design work and initial land acquisition in the 1970s, and construction of the first expressway segment beginning in 1990.

Route description

Overview

Anthony Henday Drive is a "barrier-free, illuminated, high speed, free-flow, fully access controlled facility" with a posted speed limit of 100 km/h (62 mph) for its entire length around Edmonton,[2] the first ring road of its type in Canada.[3] The majority of Capital Region residents reside within the approximate 20 km (12 mi) diameter of the ring and there is extensive suburban development in close proximity to Henday.[4] Edmonton is a physically larger city than both Toronto and Montreal, but has a relatively low population density; some have argued that the freeway is a significant contributor to urban sprawl.[5] The city also lacks a free-flowing north-south route, further increasing traffic levels on Anthony Henday Drive.[6]

The roads travels primarily through suburban residential areas in the south and west of the city, and rural farm lands and wetlands in the north.[7] The eastern section of the road separates the Sherwood Park portion of Refinery Row and other industrial and commercial developments in Edmonton to the west, from the balance of Sherwood Park to the east.

At its widest point east of Edmonton between Whitemud Drive and Sherwood Park Freeway, Anthony Henday Drive is eight total lanes wide which includes three main travel lanes in each direction plus a fourth lane allowing traffic to merge onto and exit from the roadway. The highest number of through lanes is seven, between Aurum Road and 153 Avenue in northeast Edmonton.[2] The entire road is paved with asphalt, except for an experimental 14.4 km (8.9 mi) concrete segment in southwest Edmonton, the first of its type in the province.[8] Alberta Transportation intended for the section to have lower long-term maintenance costs, but only six years after construction it required significant repairs.[9] Concrete was not considered for subsequent sections of the road, but overall it was deemed to be a successful experiment that would net long term savings.[4]

In Strathcona County southeast of Edmonton, a short 2 km (1.2 mi) section of Anthony Henday Drive (Highway 216) between Whitemud Drive and Highway 14 is concurrent with Highway 14. In west Edmonton, Anthony Henday Drive is concurrent with Highway 2 for 6.8 km (4.2 mi) between Whitemud Drive and Yellowhead Trail. Both concurrencies are unsigned; the only route shield that appears on Anthony Henday Drive is 216.[1][6]

Interchanges

Alberta Transportation used several different interchange designs for the freeway, the most common being the partial cloverleaf ranging from four to six total ramps. This type of interchange is ideal for connections between freeways and arterial roads; they have a higher capacity than diamond interchanges, but do not have the weaving and merging problems of full cloverleaf interchanges. Loop ramps are also used to better conform to existing terrain or structures, or to increase merge/weave distances between closely spaced interchanges.[10] For example, they were used at 91 Street to achieve at least 600 m (2,000 ft) of separation to Gateway Boulevard, which would not have been possible with a conventional diamond.[11] A hybrid interchange commonly called the cloverstack is constructed at the most major junctions. They allow for high speed left turns on elevated directional ramps at a posted speed limit of either 70 km/h (43 mph) or 80 km/h (50 mph), but retain loop ramps for the lesser used left turn movements significantly reducing cost and overall size of the interchange because fourth level flyovers are not required like in a stack interchange.[2][12]

Traffic

The busiest section of Anthony Henday Drive is in west Edmonton between 87 Avenue and Stony Plain Road where it carries over 105,000 vehicles per day, second only to Whitemud Drive among Edmonton roadways.[13] The 4-lane section of the southwest quadrant between Calgary Trail and Whitemud Drive is significantly over capacity and sees major delays during peak periods.[14] A contributing factor is the close proximity of interchanges between the North Saskatchewan River and Yellowhead Trail, which creates a problem known as weaving in which high volumes of traffic are trying to simultaneously enter and exit the roadway at the same time. Traffic levels on Henday have risen much more quickly than anticipated. Alberta Transportation concedes that in 2001 the southwest section was projected to reach 40,000 vehicles per day by 2020 but reached that mark in 2009; as of 2015 it carries approximately 80,000 vehicles per day in the vicinity of 111 Street.[13] Despite this, project manager Bill van der Meer has stated that Henday is operating efficiently, aside from peak hour congestion.[4] Planning is underway to determine which sections should be prioritized for widening.[4]

Alberta Transportation publishes yearly traffic volume data for provincial highways.[13] The table below compares the AADT at several locations along Anthony Henday Drive using data from 2000, 2010 and 2015, expressed as an average daily vehicle count over the span of a year (AADT). Data has not yet been provided for the northeast quadrant of the road between Manning Drive and Yellowhead Trail which opened in late 2016.

| Location | Edmonton | Strathcona County | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Section | 127 St. – Hwy. 28 | Hwy. 16 – R. Gibbon Dr. |

87 Ave. – Stony Plain Rd. |

N. SK. River (Southwest) |

Calgary Tr. – 111 St. |

50 St. – 91 St. | Yellowhead Tr. – Baseline Rd. |

S. Park Fwy. – Whitemud Dr. | |

| Traffic volume (AADT) | |||||||||

| 2000 | 21,980 | 26,200 | 19,590 | ||||||

| 2010 | 53,540 | 43,450 | 50,160 | 45,550 | 42,840 | 48,850 | |||

| 2015 | 42,700 | 59,350 | 105,370 | 76,340 | 80,050 | 64,430 | 45,510 | 50,380 | |

| Section | Hwy 14 – 50 St. |

50 St. – 91 St. |

91 St. – Whitemud[i] |

Whitemud – 87 Ave. |

87 Ave. – St. Albert Tr. |

St. Albert Tr. – Victoria Tr. |

Victoria Tr. – 153 Ave. |

130 Ave. – Aurum Rd. |

Aurum Rd. – Hwy 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clockwise | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Counter-clockwise | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| ↑In this table, Whitemud refers to the interchange of Whitemud Drive in west Edmonton, not the junction in Strathcona County east of Edmonton. | |||||||||

History

Early plans

.jpg)

The road is named after Isle of Wight explorer Anthony Henday, who travelled up the North Saskatchewan River to the area now known as Edmonton in the 18th century on a mission for the Hudson's Bay Company.[16][17] Plans for a ring road around Edmonton began developing in the 1950s when the Edmonton Regional Planning Commission identified a need for the road to support future development in the Edmonton area, as well as the movement of goods and services around the province. Areas around the city that could potentially interfere with this growth were retained by the province and called a Restricted Development Area.[7] In 1972, Edmonton City Council recommended that the city ask for the province to pay for the ring road.[18] Shortly thereafter, the Alberta provincial government led by Premier Peter Lougheed continued land acquisitions to assemble a transportation utility corridor (TUC).[19] Plans had evolved to provide right of way for future overhead high-voltage transmission lines, underground gas and oil pipelines, and water/storm sewer lines.[20] By 1985, a study had been completed to plot an exact alignment of Anthony Henday Drive through the TUC and by the end of the decade most of the required land had been purchased from land owners.[7] Unused land within the corridor may be leased out by the government as a source of revenue,[21] but some landowners were unhappy that the province did not have a firm timeline for Henday's construction.[22]

South construction

With its CANAMEX designation,[23] the southwest quadrant of the ring was deemed to be the highest priority for construction, bypassing Edmonton to the southwest by connecting Highways 2 and 16.[24] The first section of the bypass to be completed was from Whitemud Drive north to Stony Plain Road; it was constructed by the City of Edmonton beginning in 1990, and was completed in 1992 prior to the province taking over responsibility of the project.[25] An additional 4 km (2.5 mi) extending the road north to Yellowhead Trail was completed by 1998.

Construction then shifted south, with completion of the road from Whitemud Drive south to 45 Avenue just north of what is currently the Lessard Road interchange. The next section to be completed was key, extending the road on expandable twin bridge structures across the North Saskatchewan River to Terwillegar Drive on November 8, 2005.[26] An extension further east to Calgary Trail was completed by October 2006, creating a full southwest bypass of Edmonton.[27] A $168 million interchange that included seven bridges was constructed at Stony Plain Road,[28] and the entire quadrant became free-flowing in late 2011 after the completion of smaller interchanges at Lessard Road, Callingwood Road, and Cameron Heights Drive.[29] A flyover was originally planned on the western leg at 69 Avenue before it was ultimately scrapped by Alberta Transportation.[30] The total cost of the entire 24 km (15 mi) southwest quadrant from Yellowhead Trail to Gateway Boulevard was $577 million.[4]

In 2003, Alberta began design work for the 11 km (6.8 mi) southeastern section from Gateway Boulevard to Highway 14. Unlike the southwest portion, the province announced its intention to construct the road via a public-private partnership (P3), also known as a design-build-operate project.[31] This method of construction presented millions of dollars in savings to Alberta taxpayers, and allowed the project to be completed on an accelerated timeline because the consolidation of various sub-contracts are managed by one entity allowing for increased efficiencies. On January 25, 2005, Alberta signed a $493 million contract with a consortium called Access Roads to build the road and maintain it for 30 years.[31] Construction began in April and was completed in October 2007. The new segment included 24 bridge structures and 5 interchanges, and connected Highway 14 to Yellowhead Trail in the west effectively creating a full southern bypass of Edmonton. It also provided an important link for the quickly growing southern communities of Ellserlie and Summerside to the rest of Edmonton's road network.[31]

North construction and completion

| Construction overview[1] | ||||||

| Quadrant | Length (km) |

Completed (free-flowing)[lower-alpha 4] |

Cost (billions) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | 10.5 | 2007 | 0.493 | |||

| SW | 24.5 | 2011 | 0.577 | |||

| NW | 21.4 | 2011 | 1.42 | |||

| NE | 21.5 | 2016 | 1.81 | |||

| Total | 78 | 2016 | 4.3 | |||

Construction of an interim segment from Yellowhead Trail in the west to 137 Avenue was the first to be completed, as part of St. Albert's Ray Gibbon Drive project. Full work on the entire 21 km (13 mi) of the northwest leg from Yellowhead Trail to Manning Drive (Highway 15) was initiated in early 2008 after Alberta's signing of a $1.42 billion P3 agreement with Northwestconnect General Partnership to build and maintain the road for 30 years.[32] Construction began in September 2008, described by then Premier Ed Stelmach as "an important step in meeting our provincial goal of completing the ring roads to a freeway status by 2015.”[33] The project included the construction of two large cloverstack interchanges, one each at Yellowhead Trail and Manning Drive. Seven other smaller interchanges were also constructed, as well as five flyovers and two rail crossings. Three lanes each way were built from Yellowhead Trail to Campbell Road, and two lanes each way from Campbell Road to Manning Drive.[34] All work was completed on time, and the leg opened to traffic on November 1, 2011.[35]

In May 2012, Alberta signed a $1.81 billion P3 contract with Capital City Link General Partnership to build and maintain the final 9 km (5.6 mi) northeast segment of Anthony Henday Drive for 30 years after construction, from Manning Drive to Yellowhead Trail east of Edmonton in Strathcona County. A sod turning ceremony was held on July 16 and construction was underway.[36] Significant reconstruction was done to the existing section of the road east of Edmonton from Yellowhead Trail south to Highway 14 that had been in place since at least the early 1960s.[37] It was formerly known as Highway 14X, the "X" denoting that the route was an extension of Highway 14. Prior to the completion of Whitemud Drive at the end of the 1990s, Highway 14 followed a more northerly alignment through Edmonton on Sherwood Park Freeway.[38]

As part of the reconstruction, several bridges constructed between 1965 and 1974 were demolished.[37] They spanned Anthony Henday Drive at Yellowhead Trail, Baseline Road and Sherwood Park Freeway and were removed to make way for updated structures that would allow the freeway underneath to be widened to six lanes and further expanded to eight lanes or more in the future.[2][39] A bridge built in 1969 carrying Broadmoor Blvd over Yellowhead Trail[37] was also demolished because it was not at the required elevation for the new interchange configuration.[40] Yellowhead Trail from the North Saskatchewan River to Clover Bar Road was significantly improved and widened, as was Sherwood Park Freeway from 17 St to Ordze Road/Crescent in Sherwood Park.[41]

Overall, the project included the construction of nine interchanges, two road flyovers, eight rail flyovers, and twin bridges over the North Saskatchewan River for a total of 47 bridge structures.[2] Underneath the southbound bridge over the river, a pedestrian crossing was constructed and is integrated into the existing Edmonton path system. An extensive environmental assessment was also completed which identified the need for a wildlife crossing at the river, which was constructed. Noise analysis based on projected traffic volumes was also completed.[7] On October 1, 2016, the northeast leg of the freeway was officially opened to traffic.[42] Major construction on Sherwood Park Freeway and Yellowhead Trail was also largely complete including all new lanes and ramps. Only minor aesthetic work remained such as landscaping, completion of mechanically stabilized earth walls, and painting of wing walls, piers, and abutments.[43]

Future

The road was built such that it could be widened at minimal cost, with almost all bridges built wide enough for expansion to the ultimate stage which includes as many as six main travel lanes in one direction, depending on location.[44][45] Alberta has plans to widen the southwest leg of the road, which is well over capacity, but the plans are currently unfunded until at least 2020.[14][46] Plans include widening both directions from 2 to 3 travel lanes in the congested southwest section between Highway 2 and Whitemud Drive, as well as the more extensive work required to widen the bridges over the North Saskatchewan River and Wedgewood Ravine which are currently 2 lanes of travel per bridge each way.[46] In 2015, city councillor Michael Oshry stated that he was unhappy with the way the road was initially constructed, and Alberta should have done a better job of anticipating the rapid growth in southwest Edmonton.[4] Project manager Bill van der Meer disagreed, saying, "If we built a six-lane divided road that was virtually empty for 10 years, that wouldn’t be money well spent."[4]

As part of initial construction, grading was been completed for several future interchanges/flyovers and higher capacity directional ramps at existing interchanges, to reduce construction time and costs for those structures when traffic volumes require them.[34] For example, the directional ramps constructed at the northwest Henday/Yellowhead Trail interchange were built one lane wide initially, but all bridge decks are wide enough to accommodate a second lane.[44] Edmonton proposes to upgrade Terwillegar Drive to a freeway at an estimated cost of $1 billion, after which two directional ramps are proposed; they would carry traffic from northbound Terwillegar Drive to westbound Anthony Henday Drive, and from southbound to eastbound.[47] On November 1, 2016, Alberta announced the intended closure of the right-in/right-out access at 127 Street in southwest Edmonton, citing safety concerns.[48] However, in the following days, Edmonton requested that the access remain open indefinitely until alternatives were explored and the province agreed.[49] An interchange to replace this access is planned for the future, but has no funding nor an estimated completion date.[48] In the southeast, a directional ramp from eastbound Whitemud Drive to northbound Anthony Henday Drive is proposed, when traffic volumes warrant its construction.[50]

To meet long-term requirements, Alberta Transportation also proposes to construct a high capacity directional ramp carrying traffic from eastbound Anthony Henday Dive to northbound Ray Gibbon Drive after the latter is twinned and upgraded to an freeway.[51] Ray Gibbon Drive is proposed as a major corridor that will carry the Highway 2 designation in the future.[52] One kilometre further down the road at 137 Avenue, grading was initially completed for a partial cloverleaf interchange but in 2008 Alberta elected not to spend $7 million to complete paving of the ramps because development did not yet require it. St. Albert mayor Nolan Crouse was unhappy with the decision, stating that his city would not pay for it either. "It's going to sit there until there's another plan, and right now we don't have a plan... we have taken the position that we think it's the province's responsibility, and they say they won't," Crouse said.[53] As of 2016, there is no timeline for completion of the interchange.

Alberta proposes to construct a second ring road around Edmonton to support future growth, approximately 8 km (5 mi) beyond Anthony Henday Drive.[54] The road would not be constructed for roughly 40 years, and could cost upwards of $11 billion. Parkland County mayor Rod Shaigec voiced his support for the plan, stating, “if we don’t implement and have another ring road, it’s going to be further traffic congestion and have environmental impacts as well.”[55] Edmonton mayor Don Iveson calls the plan a bad idea, instead favouring expansion to Light Rail Transit and upgrades to existing roadways in the Edmonton area such as Yellowhead Trail. Both projects could be completed for the cost of the proposed outer ring road.[54]

Exit list

Exit numbering begins at Calgary Trail and increases clockwise.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Various consortiums were awarded the public–private partnership (P3) contracts for construction of the southeast, northwest, and northwest legs of Anthony Henday Drive. For the duration of the contracts, a maintenance subcontractor of each consortium is responsible for the highway. The southwest leg was not constructed via a P3 contract, so maintenance is directly contracted by Alberta Transportation.

- ↑ The entire freeway is designated as Highway 216. The short concurrencies with Highways 2 and 14 are both unsigned. In west Edmonton, Anthony Henday Drive is officially designated as Highway 2 (in addition to 216) between Whitemud Drive and Yellowhead Trail (exits 18-25). In Strathcona County east of Edmonton, Anthony Henday Drive is designated as Highway 14 between Whitemud Drive and Highway 14 (exits 64-67).[1]

- ↑ A paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Transportation Association of Canada in 2005 analyzed the construction of the bridges.[15]

- ↑ Segments of the southwest leg had been open since 1992, but it was not a freeway for its entire length until completion of the final interchange in 2011.[29]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "2016 Provincial Highway 1-216 Progress Chart" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. March 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 12, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Schedule 18 - Technical Requirements (Northeast)" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ↑ Taylor, Aaron (August 15, 2013). "A year of Henday construction done". Fort Saskatchewan Record. Sun Media. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

...the Henday into a complete ring, making it the first road of its kind in Canada.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Barnes, Dan (September 26, 2015). "Weekend read: Life in the slow lane, the saga of the Southwest Henday". Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- ↑ For a 2012 report analyzing the construction of infrastructure near the outskirts of the city, see Hoang, Linda (May 10, 2012). "Urban sprawl to cost city $1.2 billion: report". CTV News. Archived from the original on October 15, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

...there has been an increased [real estate] interest in areas on the fringes of the city. Urban sprawl... is set to cost the city $1.2 billion, according to a new report...

- For a 2016 report, see Tumilty, Ryan (March 17, 2016). "Edmonton sprawl will cost $1.4 billion more than it will bring in". Edmonton Metro News. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- For a debate regarding the use of infill, see "Infill debate continues to rage in west Edmonton neighbourhood". CBC News. Archived from the original on April 5, 2016.

Graham said infills are used to increase the density in neighbourhoods in an attempt to combat urban sprawl. He believes that Edmonton is taking responsible action by pushing for these developments. "We can't afford to keep building ring roads, so we have to find ways to increase density in these mature neighborhoods."

- 1 2 Google (November 17, 2016). "Anthony Henday Drive" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Northeast Leg – Anthony Henday Drive - Environmental Assessment - Final Report" (PDF). June 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- ↑ "First concrete roadway built by the province". Alberta Transportation. October 16, 2006. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015.

The concrete... is approximately 14 kilometres in length and is the first... built by the province.

- ↑ Ramsay, Caley (August 15, 2012). "Traffic nightmare on Anthony Henday Drive". Global News. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ↑ "A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets" (PDF). American Association of State Highway and Transportation. 2001. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- p. 860. "...interchange designs that eliminate weaving entirely or at least remove it from the main facility are desirable."

- p. 831. "...at a particular interchange site, topography and culture may be the factors that determine the quadrants in which the ramps and loops can be developed."

- ↑ "Schedule 18 - Technical Requirements (Southeast)" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. October 22, 2004. p. 37. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

The absolute minimum weaving distance on the mainline facility will be 600 m, based on attaining a minimum Level of Service C (as defined in Alberta Transportation Highway Geometric Design Guide).

- ↑ "A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets" (PDF). American Association of State Highway and Transportation. 2001. p. 844. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

A combination of directional, semidirectional, and loop ramps may be appropriate where turning volumes are high for some movements and low for others...

- 1 2 3 4 "Alberta Highways 1 to 986 - Traffic Volume History 1962 - 2015" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. February 23, 2016. pp. 101–102. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- 1 2 Barnes, Dan (September 25, 2015). "Ring of ire: Edmonton's clogged southwest Henday fires up drivers". Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ↑ Nima, Mekdam; Bassi, Paul; Middleton, David; Spratlin, Matthew (2005). "Constructability of the North Saskatchewan River Bridge" (PDF). Calgary. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2016.

- ↑ Aubrey, Merrily K.; Brugeyroux; Christie-Milley; Field; Fitzsimonds (2004). Naming Edmonton: From Ada to Zoie. The University of Alberta Press (1 ed.). Edmonton. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-88864-423-7. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- ↑ Wilson, Clifford (2003). "Henday, Anthony". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ↑ Bettison, David George; Kenward, John K.; Taylor, Larrie (1975). Urban Affairs in Alberta. University of Alberta. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-88864-009-3. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- ↑ "Paula Simons: After 26 years, Anthony Henday ring road finally comes full circle". Edmonton Journal. September 30, 2016. Archived from the original on October 2, 2016. Retrieved September 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Transportation/Utility Corridors" (PDF). Government of Alberta. 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ↑ "TUC Program Policy" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. April 16, 2004. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

Depending on the characteristics of a project and the authorizations required, [Alberta] may charge an individual or organization one or more fees for using provincial Crown lands within a TUC. [Alberta] will charge a lessee rent for a lease of provincial Crown lands within a TUC...

- ↑ Hobshawn-Smith (April 3, 2012). Foodshed: An Edible Alberta Alphabet. Touchwood Editions. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-927129-16-6. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- ↑ "CANAMEX Trade Corridor". Alberta Transportation. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

Many projects have contributed to the overall efficiency of the CANAMEX/North-South Trade Corridor, some examples include: ... The completion of the southwest quadrant of the Edmonton Ring Road.

- ↑ "Intelligent Transportation Systems Study for the Edmonton and Calgary Ring Roads" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. March 1, 2004. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2010.

AHD is part of Alberta Transportation’s initiative to provide a high standard highway trade corridor linking Alberta to the United States and Mexico. In addition, the roadway forms an important part of Edmonton’s overall transportation system and is included in the City’s Transportation Master Plan..

- ↑ "1990/1991 Annual Report" (PDF). Edmonton: Alberta Transportation and Utilities. 1992. p. 20. Retrieved November 4, 2016 – via University of Alberta Libraries.

Completed construction of a four-lane arterial road from Whitemud Drive to Stony Plain Road.

- ↑ "Alberta Infrastructure and Transportation Annual Report 2005-2006" (PDF). Alberta Infrastructure. 2006. p. 29. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

This section includes new twin bridges over the North Saskatchewan River... the bridges are designed to accommodate four lanes of traffic in the future.

- ↑ "Drivers caught in traffic as bridge work continues". CBC News. October 12, 2006. Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- For the Alberta Transportation press release, see "Province officially opens Anthony Henday Drive Southwest to 30,000 daily motorists - First completed ring road section in Alberta opens to traffic". Alberta Transportation. October 16, 2006. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Governments of Canada and Alberta fund Edmonton ring road interchange". Alberta Transportation. March 6, 2009. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- 1 2 For Lessard Road and Callingwood Road, see "Three more interchanges open on Southwest Henday for safer, smoother traffic". Alberta Transportation. November 4, 2011. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- For Cameron Heights Drive, see "Governments of Canada and Alberta to remove final set of traffic lights from Edmonton Ring Road". Alberta Transportation. March 24, 2010. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ↑ "City opts to add signage along contested Ormsby Road". CBC News. September 13, 2013. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "P3 enables Anthony Henday Drive S.E. to open in 2007". Alberta Transportation. January 25, 2005. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Construction set to begin on north Edmonton ring road". Government of Alberta. July 30, 2008. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ↑ "Construction officially starts on Northwest Anthony Henday Drive". Alberta Transportation. September 25, 2008. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- 1 2 "Schedule 13 - New Infrastructure (Northwest)" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2016. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Open road beckons drivers in northwest Edmonton". Government of Alberta. November 1, 2011. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ↑ For financial terms of the deal, see "P3 project reaches financial close". Alberta Transportation. May 18, 2012. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

...contract is worth $1.81 billion in 2012 dollars...

- For the sod turning, see Tumilty, Ryan (July 18, 2016). "Alberta kicks off Northeast Henday project". St. Albert Gazette. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

The province started closing the loop on Anthony Henday Drive Monday [July 16, 2012]...

- For the sod turning, see Tumilty, Ryan (July 18, 2016). "Alberta kicks off Northeast Henday project". St. Albert Gazette. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Transportation Infrastructure Management System - Existing Structures in the Provincial Highway Corridor" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. September 28, 2012. pp. 185–186. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- ↑ 1969 Alberta Official Highway Road Map (Map) (1969 ed.). Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Updated timeline: Baseline bridge demolition". Alberta Transportation. May 17, 2013. Archived from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ↑ Martell, Krysta (June 5, 2015). "Broadmoor bridge to be demolished". Sherwood Park News. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

“We need to shut down a section of the Yellowhead Trail to allow for the [Brooadmoor] bridge demolition... because we need to bring the entire interchange onto a higher elevation" - Vanessa Urkow/Alberta Tranportation

- ↑ "Construction digs-in on final leg of Edmonton ring road" (PDF). Government of Alberta. July 16, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ↑ "Northeast Anthony Henday Drive". Alberta Transportation. 2016. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2016.

The northeast leg of Anthony Henday Drive opened on October 1, 2016, after five years of construction...

- ↑ "Ring road around Edmonton opens today". Alberta Transportation. October 1, 2016. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- For final work, see "Alberta's first ring road now open". Journal of Commerce. October 11, 2016. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016.

...drivers will continue to see work being completed off the highway on such things as landscaping, seeding and final bridge work.

- For final work, see "Alberta's first ring road now open". Journal of Commerce. October 11, 2016. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Schedule 18 - Technical Requirements (Northwest)" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. July 29, 2008. p. 463. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

10 Lane Ultimate Stage

- ↑ Ramsay, Caley (September 14, 2016). "'It's getting close to full': Southwest leg of Anthony Henday Drive reaching capacity". Global News. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- 1 2 "Fiscal Plan/Capital Plan 2016" (PDF). Government of Alberta. 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- 1 2 ISL Engineering / Al-Terra Engineering (March 2010). "170 Street" (PDF). Concept Planning Study. City of Edmonton. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2012. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- 1 2 Stolte, Elise (November 1, 2016). "Edmonton protests province's closure of 127 Street access to Henday, key south-side link". Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on November 1, 2016.

- ↑ Mertz, Emily (November 10, 2016). "Closure of Henday exit at 127 Street postponed". Global News. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ↑ "North East Edmonton Ring Road Advanced Functional Plan - Bridge Planning Summary Report" (PDF). ISL Engineering and Land Services. March 2010. p. 9. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Schedule 18, Appendix A – Drawings Issued for Agreement (Northwest)" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. July 29, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ↑ "Alberta Transportation: Planning in the Capital Region" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

[Ray Gibbon Drive is] identified [as] an ultimate freeway corridor, which includes limited highway access & interchange locations.

- ↑ "Henday's exit to nowhere". Edmonton Journal. November 25, 2008. Archived from the original on October 4, 2009. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Parrish, Julia (July 10, 2014). "Capital Region leaders talk about building new outer ring road, Edmonton mayor calls it a 'lousy' idea". CTV News. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014.

- ↑ Barnes, Kateryna (July 10, 2014). "Push for second ring road around Edmonton hitting roadblocks". Global News. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Transportation Infrastructure Management System - Existing Structures in the Provincial Highway Corridor" (PDF). Alberta Transportation. September 28, 2012. pp. 189–194. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Anthony Henday Drive" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

External links

- Alberta Transportation - Edmonton Ring Road

- Capital City Link Group - Northeast Anthony Henday Drive