Clarence Williams (musician)

| Clarence Williams | |

|---|---|

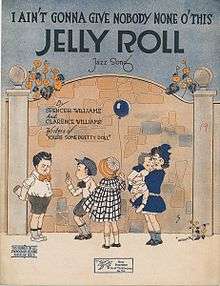

I Aint Gonna Give Nobody None O This Jelly Roll sheet music cover | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Clarence Williams |

| Born |

October 8, 1893 or October 8, 1898 (sources differ) Plaquemine, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died |

November 6, 1965 (age 67 or 72) Queens, New York, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer |

| Instruments | Piano |

| Associated acts |

Sidney Bechet Louis Armstrong Bessie Smith Eva Taylor |

Clarence Williams (October 8, 1893,[1] or October 6, 1898[2][3] – November 6, 1965)[1][2][3] was an American jazz pianist, composer, promoter, vocalist, theatrical producer, and publisher.

Biography

Williams was born in Plaquemine, Louisiana, ran away from home at age 12 to join Billy Kersand's Traveling Minstrel Show, then moved to New Orleans. At first Williams worked shining shoes and doing odd jobs, but soon became known as a singer and master of ceremonies. By the early 1910s he was a well regarded local entertainer also playing piano, and was composing new tunes by 1913. Williams was a good businessman and worked arranging and managing entertainment at the local African-American vaudeville theater as well as at various saloons and dance halls around Rampart Street, and at clubs and houses in Storyville.[1][4]

Williams started a music publishing business with violinist/bandleader Armand J. Piron in 1915, which by the 1920s was the leading African-American owned music publisher in the country. He toured briefly with W.C. Handy, set up a publishing office in Chicago, then settled in New York in the early 1920s. In 1921, he married blues singer and stage actress Eva Taylor, with whom he would frequently perform.[1][4]

He was one of the primary pianists on scores of blues records recorded in New York during the 1920s. He supervised African-American recordings (the 8000 Race Series) for the New York offices of Okeh phonograph company in the 1920s in the Gaiety Theatre office building in Times Square.[5] He recruited many of the artists who performed on that label. He also recorded extensively, leading studio bands frequently for OKeh, Columbia and occasionally other record labels.[1][4]

He mostly used "Clarence Williams' Jazz Kings" for his hot band sides and "Clarence Williams' Washboard Five" for his washboard sides. He also produced and participated in early recordings by Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, Bessie Smith, Virginia Liston, Irene Scruggs, his niece Katherine Henderson,[6] and many others. Two of his 1924 recording bands, "The Red Onion Jazz Babies" and "Clarence Williams' Blue Five" featured cornetist Armstrong and soprano saxophonist Bechet, two of the most important early jazz soloists, in their only recordings together before the 1940s. The rivalry between Armstrong and Bechet, who tried to outdo each other with successive solo breaks, is exemplified in "Cake Walkin' Babies from Home", the most celebrated of these performances, which survives in versions recorded by both bands.[7] King Oliver played cornet on a number of Williams's late 1920s recordings. He was the recording director for the short-lived QRS Records label in 1928.[1][4]

Most of his recordings were songs from his publishing house, which explains why he recorded tunes like "Baby Won't You Please Come Home", "Close Fit Blues" and "Papa De-Da-Da" numerous times.[8] Among his own compositions was "Shout, Sister, Shout" (1929), which was recorded by him, and also covered by the Boswell Sisters, in 1931.[1][4]

In 1933, he signed to the Vocalion label and recorded quite a number of popular recordings, mostly featuring washboard percussion, through 1935 (and a session in 1938).[1][4] He also recorded for Bluebird in 1937, and again in 1941.

In 1943, Williams sold his extensive back-catalogue of tunes to Decca Records for $50,000 and retired, but then bought a bargain used-goods store. Williams died in Queens, New York City, in 1965, and was interred in Saint Charles Cemetery in Farmingdale on Long Island. On her death in 1977, his wife, Eva Taylor, was interred next to him.[1][4]

Clarence Williams is the grandfather of actor Clarence Williams III.[2] His daughter Joy Williams (1931–1970) was a singer-actress under stage name Irene Williams.

Work and influence

Clarence Williams' name appears as composer or co-composer on numerous tunes, including a number which by Williams' own admission were written by others but which Williams bought all rights to outright, as was a common practice in the music publishing business at the time. Clarence Williams was also credited as the author of Hank Williams' 1949 hit "My Bucket's Got a Hole in It", a song that was later recorded by Louis Armstrong. In 1970, Williams was posthumously inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame.[1][4]

Clarence Williams hits include

- "I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate" (as publisher – not composer)

- "Baby Won't You Please Come Home"

- "Royal Garden Blues"

- "Ain't Nobody's Business If I Do"

- "Shout, Sister, Shout"

- "You Rascal You"

- "You Missed A Good Woman"

- "That Ought To Do It"

- "Look What A Fool I've Been"

- "Got To Cool My Doggies Now"

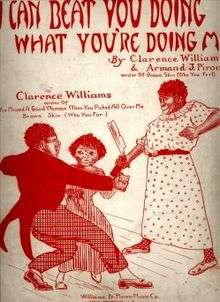

- "I Can Beat You Doing What You're Doing Me"

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jazz vocalists from the United States. |

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Clarence Williams Biography". Songwriters Hall of Fame.

- 1 2 3 "Clarence Williams: Composer, Producer, Director, Performer, Writer, Lyricist, Musical Director". Internet Broadway Database (The Broadway League). Archived from the original on June 1, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- 1 2 "Clarence Williams, Entrepreneur and Jazz and Blues Artist". African American Registry. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Music of Clarence Williams". Basin Street. Archived from the original on July 13, 2015.

- ↑ Broadway: An Encyclopedia by Ken Bloom – Routledge; 2 edition (November 11, 2003) ISBN 0-415-93704-3

- ↑ "Katherine Henderson accompanied by Clarence Williams and his Orchestra". Redhotjazz.com. Retrieved 2014-09-13.

- ↑ Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy: Gennett Records and the Rise of America's Musical Grassroots by Rick Kennedy, 1/18/2013, ISBN 978-0-253-00747-6, p. 87

- ↑ Lockhart, John M. "Words & Music", The Riverside Reader, February 4, 2008, p. 5

External links

- Clarence Williams on RedHotJazz.com; biography with photos and ram files of vintage recordings

- Clarence Williams by Tom Morgan

- Clarence Williams at Jass.com