Lazare Carnot

| Lazare Carnot | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the National Convention | |

|

In office 20 May 1794 – 4 June 1794 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Lindet |

| Succeeded by | Claude-Antoine Prieur-Duvernois |

| Member of the Committee of Public Safety | |

|

In office 14 August 1793 – 6 October 1794 | |

| Member of the Directory | |

|

In office 4 November 1795 – 5 September 1797 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | Philippe-Antoine Merlin de Douai |

| Minister of War | |

|

In office 2 April 1800 – 8 October 1800 | |

| Preceded by | Louis-Alexandre Berthier |

| Succeeded by | Louis-Alexandre Berthier |

| Minister of the Interior | |

|

In office 20 March 1815 – 22 June 1815 | |

| Monarch | Napoleon I |

| Preceded by | François-Xavier-Marc-Antoine de Montesquiou-Fézensac |

| Succeeded by | Claude Carnot-Feulin |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

13 May 1753 Nolay, Côte-d'Or |

| Died |

2 August 1823 (aged 70) Magdeburg, Prussia |

| Political party | Independent |

| Children |

Sadi Carnot Lazare Hippolyte Carnot |

| Profession | Mathematician, engineer, military commander, politician |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Lazare Nicolas Marguerite, Comte Carnot (13 May 1753 – 2 August 1823), the Organizer of Victory in the French Revolutionary Wars, was a French politician, engineer, freemason[1][2] and mathematician.

Education and early life

Born in Nolay, Côte-d'Or, Carnot was educated in Burgundy at the Collège d’Autun, an artillery and engineering prep school. He graduated from Mézières School of Engineering, where he had met and studied with Benjamin Franklin,[3] at the age of twenty and obtained commission as a lieutenant in the Prince of Condé’s engineer corps. It was here that he early made a name for himself both in the line of (physics) theoretical engineering and in his work in the field of fortifications. While in the army, he continued his study of mathematics. In 1784 he published his first work Essay on Machines which contained a statement that foreshadowed the principle of energy as applied to a falling weight, and the earliest proof of the fact that kinetic energy is lost in the collision of imperfectly elastic bodies. This publication earned him the honour of admittance to a literary society. In that same year, he also received a promotion to the rank of captain.

Political career

At the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, Carnot entered political life. He became a delegate to the Legislature in 1791. While a member of the Legislative Assembly, Carnot was elected to the Committee for Public Instruction. He believed that all citizens should be educated and as a member of that committee, he wrote a series of reforms for the teaching and educational systems, but they were not implemented due to the violent social and economic climate of the Revolution.

After the Legislative Assembly was dissolved, Carnot was elected to the National Convention in 1792. He spent the last few months of 1792 on a mission to Bayonne, organizing the military defense effort in an attempt to ward off any possible attacks from Spain. Upon returning to Paris, Carnot voted for the death of King Louis XVI, although he had been absent for the debates surrounding the king’s trial.[4]

On 14 August 1793 Carnot was elected to the Committee of Public Safety, where he took charge of the military situation as one of the Ministers of War.[4]

The creation of the French Revolutionary Army was largely due to his powers of organization and enforcing discipline. In order to raise more troops for the war, Carnot introduced conscription: the levée en masse approved by the National Convention was able to raise France’s army from 645,000 troops in mid-1793 to 1,500,000 in September 1794. Once the problem of troop numbers had been solved, Carnot turned his administrative skills to the supplies that this massive army would need. Many of the munitions and supplies were in short supply: copper was lacking for guns so he ordered church bells seized in order to melt them down; saltpeter was lacking and he called chemistry to his aid; leather for boots was scarce so he demanded and secured new methods for tanning. He quickly organized the army and helped to turn the tide of the war. It added significantly to discontent with the course of the Revolution in still Bourbon-loyalist areas – such as the Vendée, which had broken out in open revolt 5 months earlier – but the government of the time considered it a success, and Carnot became known as the Organizer of Victory. [4] In autumn 1793, he took charge of French columns on the Northern Front, and contributed to Jean-Baptiste Jourdan's victory in the Battle of Wattignies.

Carnot had taken no steps to oppose the Reign of Terror, but he and some other technocrats on the committee, including Robert Lindet and Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau, turned on Maximilien Robespierre and his allies during the Thermidorian Reaction.

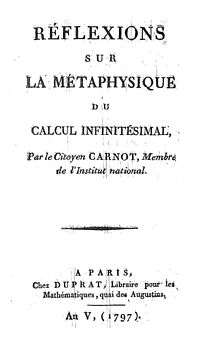

With the establishment of the Directory in 1795, Carnot became one of the five initial directors. For the first year the Directors did well working harmoniously together as well as with the Councils. However, difference of political views led to a schism between Carnot and Étienne-François Letourneur, followed by François de Barthélemy, on the one side, and the triumvirate of Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras, Jean-François Rewbell, and Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux on the other side. Carnot and Barthélemy supported concessions to end the war, and hoped to oust the triumvirate and replace them with more conservative men. His and Étienne-François Letourneur's moderation was viewed as weakness, and it probably contributed to France's failure to capitalize on the Treaty of Campo Formio. After Letourneur had been replaced by another close collaborator of Carnot, François de Barthélemy, both of them, alongside many deputies in the Council of Five Hundred, were ousted in the Coup of 18 Fructidor (4 September 1797), engineered by Generals Napoleon Bonaparte (originally, Carnot's protégé) and Pierre François Charles Augereau. Carnot took refuge in Geneva, and there in 1797 issued his La métaphysique du calcul infinitésimal.

In 1800 Bonaparte appointed Carnot as Minister of War, and he served in that office at the time of the Battle of Marengo. In 1802 he voted against the establishment of Napoleon's Consular powers for life and the passing of the title to his children, for as Carnot said when speaking of the power necessary to govern a state "If this power is the appendage of a hereditary family it becomes despotic."

Retirement

After Napoleon crowned himself emperor on 2 December 1804, Carnot's republican convictions precluded his acceptance of high office under the First French Empire, and he resigned from public life – although he was later made a Count of the Empire by Napoleon as Lazare Nicolas Marguerite, comte Carnot.

In 1803 Carnot produced his Géométrie de position. This work deals with projective rather than descriptive geometry. Carnot is responsible for initiating the use of cross-ratios: "He was the first to introduce the cross (anharmonic) ratio of four points of a line taking account of its sign, thereby sharpening Pappus' concept. He then proved that this ratio is invariant for the four points obtained by cutting four lines of a pencil of lines with different secants. In this way he established the harmonic properties of the complete quadrilateral."[5] This approach to geometry was used by Karl von Staudt four decades later to set a new foundation to mathematics.

The Borda–Carnot equation of fluid dynamics and Carnot's theorem in plane geometry are named after him.

Probably in response to the fall of the fortress of Vlissingen to the British during the Walcheren Campaign in 1809, Napoleon employed Carnot to write a treatise describing how fortifications could be improved, for the use of the École militaire de Metz. Building on the theories of the controversial engineer Montalembert, Carnot advanced ideas on how the long established bastioned system of fortification could be modified for close defence and to allow for counter attack by the besieged garrison. Published in 1810 under the title "Traité de la Défense des Places Fortes", his ideas were further developed in the third edition which was published in 1812. An English translation, "A Treatise on the Defence of Fortified Places" was published in 1814. Although few of his proposals were accepted by mainstream engineers, the Carnot wall, a detached wall at the foot of the escarp, became a common feature in fortifications built in the mid-19th century.[6]

Carnot returned to office in defense of Napoleon during the disastrous invasion of Russia; he was assigned the defense of Antwerp against the Sixth Coalition – he only surrendered on the demand of the Count of Artois, who was the younger brother of Louis XVIII and later Charles X.

During the Hundred Days, Carnot served as Minister of the Interior for Napoleon, and was exiled as a regicide during the White Terror after the Second Restoration during the reign of Louis XVIII. He lived in Warsaw, and moved to Prussia, where he died in the city of Magdeburg. Carnot's remains were interred at the Panthéon in 1889, at the same time as those of Marie Victor de La Tour-Maubourg, Jean-Baptiste Baudin, and François Séverin Marceau-Desgraviers.

Impact

Carnot was able to survive during all the phases of the French Revolution, from its beginnings in 1789 until the fall of Napoleon in 1815. On the social and political front, Carnot was the author of many reforms that he thought to be for the good of the Republic. One of these was the proposal for compulsory public education for all citizens. He also penned a proposal for the new Constitution which included the "Declaration of the Duties of the Citizens" that held that there should be not only education but military service for all citizens of France between the ages of twenty and twenty-five.[3] These proposals were in accordance with the Revolutionaries' thinking at the time, which held that men and women should be honored through ability and intelligence rather than through birthright, even though Carnot himself was nobly born. This style of thinking may well have been instrumental in Napoleon Bonaparte's rise to power as it was Carnot who promoted him from Captain to General.[7]

But perhaps his greatest achievements, in reference to the French Revolution itself, were those of a military nature. As Carnot was the first to execute the modern waging of war with mass armies and strategic planning realized by the Revolution.[3] As a military engineer, Carnot favored fortresses and defensive strategies,[7] but with the constant invasions decided to take his strategic planning to an offensive strike. From his intellect sprang the maneuvers and organization that turned the tides of war from 1793 to 1794.[8] The basic idea was to have a massive army separated into several units that could move more quickly than the enemy and attack from the flanks rather than head on, which had led to resounding defeats before Carnot was elected to the Committee of Public Safety. This tactic was extremely successful against the more traditional tactics of existing European armies. It was his initiative to train the conscripts in the art of war and to place new recruits with experienced soldiers rather than having a massive volunteer army without any real idea of how to wage battle. He also created a new political strategy based on disrupting communication between France's enemy nations of England and Austria while concentrating attack effort on England. Carnot’s military influence and authority were eventually used to bring about the downfall of Robespierre.[3]

Work in mathematics and Theoretical Engineering

- Lazare Carnot: De la corrélation des figures de géométrie, 1801

- Lazare Carnot: Réflexions sur la métaphysique du calcul infinitésimal (English translation: Reflexions on the metaphysical principles of the infinitesimal analysis, 1832 )

- Lazare Carnot: A treatise on the defence of fortified places, 1814

He also published essays about engineering theory. Essai sur les machines en général won honorable mention from the Academie sur Science of Paris in 1780. It was revised and published in 1783. In this he outlined a mathematical theory of power transmission in mechanical systems. His essay Principes fondamentaux de l'équilibre et du mouvement 1803 was a further revision and expansion of the earlier work. This was "the first theoretical analysis of engineering mechanics". In this "he went on to analyze the movement of energy from one part of the system to another; he found that power is transmitted most efficiently, and the largest amount of useful work done, when friction, turbulence, and other energy wasting factors are kept to a minimum. This was an early and incomplete approach to the general law of conservation of energy." Engineer, "Sadi Carnot (his son) was influenced by his father's work when he undertook his research into the thermal efficiency of the steam engine."

[9]Great Engineers and Pioneers in Technology Vol1 Ed Roland Turner and Steven Goulden St Martins Press Inc NY 1981

His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Famous offspring

- His son Sadi Carnot was a founder of the field of thermodynamics and the theory of heat engines (see Carnot cycle).

- His second son Lazare Hippolyte Carnot was a French statesman.

- His grandson Marie François Sadi Carnot (son of Hippolyte) was President of the French Republic from 1887 until his assassination in 1894.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Dictionnaire universel de la Franc-Maçonnerie (Monique Cara, Jean-Marc Cara, Marc de Jode, ed. Larousse, 2011)

- ↑ Histoire de la Franc-Maçonnerie française, (Pierre Chevallier, ed. Athène Fayard, 1975)

- 1 2 3 4 Dino De Paoli, Lazare Carnot's Grand Strategy for Political Victory. Executive Intelligence Review (1996)

- 1 2 3 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ B. L. Laptev & B. A. Rozenfel'd (1996) Mathematics of the 19th Century: Geometry, p. 28, Birkhäuser Verlag ISBN 3-7643-5048-2

- ↑ Lloyd, E. M. (1887), Vauban, Montalembert, Carnot: Engineer Studies, Chapman and Hall, London (pp. 183-195)

- 1 2 R.R. Palmer, The Twelve Who Ruled. Princeton: Princeton University Press (1941)

- ↑ S.J. Watson. Carnot.London:The Bodley Head (1954)

- ↑ Great Engineers and Pioneers in Technology Turner & Goulden P314-315

References

- James R. Arnold, The Aftermath of the French Revolution. Minneapolis, MN: Twenty-First Century Books (2009)

- W. W. Rouse Ball, A Short Account of the History of Mathematics (4th Edition, 1908)

- Brett-James, Anthony. The Hundred Days; Napoleon's Last Campaign from Eye-Witness Accounts. London: McMillan (1964)

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Carnot, Lazare Nicolas Marguerite". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Carnot, Lazare Nicolas Marguerite". Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Gagnon, Paul A. France Since 1789. New York: Harper & Row (1964)

- Furet, François and Mona Ozouf, eds. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (1989), pp. 197–203

- Charles Coulston Gillispie, Lazare Carnot, Savant, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08082-8 (1971)

- David Hamilton-Williams. Waterloo: New Perspectives. The Great Battle Reappraised. New York: John Wiley & Sons (1994)

- Daniel P. Resnick. The White Terror and the Political Reaction After Waterloo. Cambridge: Harvard University Press (1966)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lazare Carnot |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lazare Carnot. |

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Lazare Carnot", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- MathPages – Carnot, Organizer of Transversals

- Lazare Carnot - Œuvres complètes Gallica-Math

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Louis Alexandre Berthier |

Ministers of War 2 April 1800 – 8 October 1800 |

Succeeded by Louis Alexandre Berthier |

| Preceded by François Xavier de Montesquiou-Fezensac |

Ministers of Interior 20 March 1815 – 22 June 1815 |

Succeeded by Claude Carnot-Feulin |

._D%C3%A9claration_des_Droits_et_des_Devoirs_de_l'Homme_et_du_Citoyen.jpg)