Cole Younger

| Thomas Cole Younger | |

|---|---|

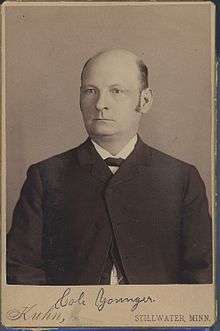

Portrait of Cole Younger taken when he was a prisoner at the Minnesota State Prison ca. 1889 | |

| Born |

Thomas Coleman Younger January 15, 1844 Jackson County, Missouri, USA |

| Died |

March 21, 1916 (aged 72) Lee's Summit, Missouri, USA |

| Resting place |

Lee's Summit Cemetery / Andrews Fist 38°55′2″N 94°21′45″W / 38.91722°N 94.36250°W |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for |

|

| Parent(s) | |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Thomas Coleman "Cole" Younger (January 15, 1844 – March 21, 1916) was an American Confederate guerrilla during the American Civil War and later a leader with the James–Younger Gang. He was the eldest brother of Jim, John and Bob Younger.

Early life

Thomas Coleman "Cole" Younger, was born on January 15, 1844 on the Younger family farm. He was a son of Henry Washington Younger, a prosperous farmer from Greenwood, Missouri and Bersheba Leighton Fristoe, daughter of a prominent Jackson County farmer. Cole was the seventh of fourteen children.

Civil War

During the American Civil War, savage guerrilla warfare wracked Missouri. Younger's father was pro-Union, but he was shot dead anyway by a Union soldier from Kansas. After that, Cole Younger sought revenge as a pro-Confederate guerrilla under William Clarke Quantrill. After the early part of the war, the Confederate Army withdrew from the state and the fighting was mainly between pro-Union and pro-Confederate Missourians. However, the bushwhackers held a special hatred for the "red leg" Union troops from Kansas who frequently entered Missouri and earned a reputation for ruthlessness. Younger rode with Quantrill in a retaliation raid on Lawrence, Kansas on August 21, 1863, during which about 200 citizens were killed and the town looted and burned.[1]

Younger said he left the bushwhackers and enlisted in the Confederate Army. He claimed he was sent to California on a recruiting mission. He returned after the war's end to find Missouri ruled by a militant faction of Unionists Radicals. In the last days of the war, the Radicals had pushed through a new state constitution that barred all Confederate sympathizers from voting, serving on juries, holding public office, preaching the gospel, or carrying out many public roles. The constitution freed the slaves in advance of the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It enacted a number of reforms, but the restrictions on former Confederates created disunity.

Bandit career

Most of the former bushwhackers returned to peaceful lives. Many left Missouri for friendlier places, particularly Kentucky, where many had relatives. Most of their leaders, including Quantrill and "Bloody Bill" Anderson, had been killed in the war. But a small core of Anderson's men, led by the ruthless Archie Clement, remained together. State authorities believed that Clement planned and led the first daylight peacetime armed bank robbery in U.S. history, holding up the Clay County Savings Association on February 13, 1866. The bank was run by the leading Radicals of Clay County, who had just held a public meeting for their party. The governor posted a reward for Clement, but he and his men conducted further robberies that year. On election day of 1866, Clement led his men into Lexington, Missouri, where they intimidated Radical voters and secured the election of a conservative slate of candidates. A state militia unit entered the town shortly thereafter and killed Clement when he resisted arrest.

It is uncertain when Cole Younger and his brothers joined this gang. The first mention of his involvement came in 1868, when authorities identified him as a member of a gang who robbed Nimrod Long & Co., a bank in Russellville, Kentucky. Former guerrillas, John Jarrett (brother in law of Cole Younger), Arthur McCoy, and George and Oliver Shepard were also implicated. Oliver Shepard was killed resisting arrest and George was imprisoned. Once the more senior members of the gang had been killed, captured, or quit, its core thereafter consisted of the James and Younger brothers.[2]

Witnesses repeatedly gave identifications that matched Cole Younger in robberies carried out over the next few years, as the outlaws robbed banks and stagecoaches in Missouri and Kentucky. On July 21, 1873, they turned to train robbery, derailing a locomotive and looting the express car on the Rock Island Railroad in Adair, Iowa. Younger and his brothers were also suspects in hold-ups of stage coaches, banks, and trains in Missouri, Kentucky, Kansas, and West Virginia.

Following the robbery of the Iron Mountain Railroad at Gad's Hill, Missouri, in 1874, the Pinkerton National Detective Agency began to pursue the James and Younger brothers. Two agents (Louis J. Lull and John Boyle) engaged John and Jim Younger in a gunfight on a Missouri road on March 17, 1874; Boyle fled the scene, and both John Younger and Lull were killed. Simultaneously, another Pinkerton agent W.J. Whicher [3] who pursued the James brothers was abducted and later found dead alongside a rural road in Jackson County, Missouri.

Some Younger families changed their last names to Jungers to avoid a family association with the gangsters.

The James and Younger brothers survived capture longer than most Western outlaws because of their strong support among former Confederates. Jesse James became the public face of the gang, appealing to the public in letters to the press.

Downfall of the gang

On September 7, 1876 the James-Younger Gang attempted to rob a bank in Northfield, Minnesota. Cole Younger and his brother Bob both later said that they selected the bank because of its connection to two former Union generals and Radical Republican politicians, Benjamin Butler and Adelbert Ames. Three of the outlaws entered the bank, as the remaining five, led by Cole Younger, remained on the street to provide cover. The crime soon went awry, however, when the townspeople sent up the alarm and ran for their guns. Younger and his brothers began to fire in the air to clear the streets, but the townspeople (shooting from under cover, through windows and around the corners of buildings) opened a deadly fusillade, killing gang members Clell Miller and William Chadwell and badly wounding Bob Younger through the elbow. Herb Potter rode off in a hail of bullets. The outlaws killed two townspeople, including the acting cashier of the bank, and fled empty-handed. As hundreds of Minnesotans formed posses to pursue the fleeing gang, the outlaws separated. The James brothers made it back to Missouri, but the three Youngers (Cole, Bob, and Jim) did not. They and another gang member, Charlie Pitts, waged a gun battle with a local posse in a wooded ravine along the Watonwan River west of Madelia, Minnesota. Pitts was killed, and Cole, Jim, and Bob Younger were badly wounded and captured. Cole, asked about the robbery, responded, "We tried a desperate game and lost. But we are rough men used to rough ways, and we will abide by the consequences."

Cole, Jim and Bob pleaded guilty to their crimes to avoid being hanged. They were sentenced to life in prison at the Stillwater Prison at Stillwater on November 18, 1876. Frank and Jesse James fled to Nashville, Tennessee, where they lived peacefully for the next three years. In 1879, Jesse returned to a life of crime, ending in his murder on April 3, 1882, in Saint Joseph, Missouri. Frank James surrendered to Missouri Governor Thomas T. Crittenden on October 4, 1882. Eventually Frank James was acquitted, and lived quietly and peacefully thereafter. Herb Potter was shot and killed while taking up with another man's wife in December 1883.

Bob Younger died in Stillwater prison on September 16, 1889, of tuberculosis. Cole and Jim were paroled on July 10, 1901, with the help of the prison warden. Jim committed suicide in a hotel room in St Paul, Minnesota, on October 19, 1902. Cole wrote a memoir that portrayed himself as a Confederate avenger more than an outlaw, admitting to only one crime, that at Northfield. He lectured and toured the south with Frank James in a wild west show, The Cole Younger and Frank James Wild West Company in 1903. On August 21, 1912, Cole declared that he had become a Christian and repented of his criminal past.

Frank James died February 18, 1915. A year later, Cole Younger died March 21, 1916, in his home town of Lee's Summit, Missouri, and is buried in the Lee's Summit Historical Cemetery.[2]

Films

- The 1941 movie Bad Men of Missouri featured Younger (played by Dennis Morgan) and his two outlaw brothers fighting the bank.

- The 1949 movie The Younger Brothers had Wayne Morris play Cole in a fictional story of the Youngers receiving their pardon.

- The 1957 movie The True Story of Jesse James, directed by Nicholas Ray, featured Alan Hale, Jr. as Younger.

- The 1958 movie Cole Younger, Gunfighter featured Cole played by Frank Lovejoy.

- In 1960, Robert J. Wilke (1914–1989) played Younger in the episode "Perilous Passage", the series premiere of the NBC western Overland Trail, starring William Bendix and Doug McClure.

- In 1960, Bronco TV Western episode "Shadow of Jesse James" told the story of the Northfield Bank Robbery

- In "One Way Ticket", a 1962 episode of Cheyenne, Clint Walker, in the title role of Cheyenne Bodie, is a federal marshal escorting Younger, played by Philip Carey, to prison to begin his sentence.

- The 1972 movie The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid depicts this failed bank robbery, with Cliff Robertson as Cole Younger.

- The 1980 movie The Long Riders depicts this era of the James-Younger gang exploits (with David Carradine playing Cole).

- The 1994 movie Frank and Jesse depicts the James-Younger gangs outlaw days (with Randy Travis playing Cole).

- The TV series Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman featured Cole portrayed by Ian Bohen in the episode "Baby Outlaws S3E21"

- The 2001 movie American Outlaws depicts the early years of the James-Younger Gang (with Scott Caan playing Cole)

- The 2010 version of True Grit depicts Younger operating his Wild West show (with Don Pirl playing Cole)

In television

In the episode "One Way Ticket" of the ABC/Warner Brothers western series, Cheyenne, Philip Carey plays Cole Younger, who in the story line is being transported by railway to the penitentiary in Denver, Colorado. The Clint Walker character Cheyenne Bodie, in this episode a United States marshal, is assigned to guard Younger, but Bodie encounters one distraction after another, including friendship with a widow and her ten-year-old son played by Maureen Leeds and Ronnie Dapo, respectively. Twice Younger escapes, but he ultimately decides based on Bodie's stern advice to accept prison with the hope of a later pardon. Younger in the episode says that Bodie is so convincing that he should have been a "politician or a preacher."[4]

In the episode ‘’The Younger Brothers’ Younger Brother’’ (Season 13, Episode 23) of the western television show Bonanza, Cole Younger (Strother Martin) and his brothers are released from prison and again take up a life of crime that has them cross paths with Hoss Cartwright, who is then mistaken for one of the brothers.[5]

Cole Younger is the main antagonist in the Hulu Original Series Quick Draw. In the show he is characterized by a large leather mask that he wears in perpetuity, and the only reference to a brother is his follower: Ephram Younger. The character resides just outside the town of Great Bend, Kansas and is played by Brian O'Connor.[6]

In literature

Cole Younger appears briefly towards the end of Charles Portis' 1968 novel True Grit.

Cole Younger is a major character in Wildwood Boys (William Morrow, 2000; New York), a biographical novel of "Bloody Bill" Anderson by James Carlos Blake.

References

- ↑ John Simkin (September 1997). "Cole Younger". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- 1 2 Carlyn Trout. "Thomas Coleman "Cole" Younger". The State Historical History of Missouri. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ↑ The story of Cole Younger by himself: being an autobiography of the Missouri ...By Cole Younger

- ↑ One Way Ticket at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ The Younger Brothers’ Younger Brother at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Quick Draw TV Series, Outlaw: Cole Younger". SFGate. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

Further reading

- Brant, Marley (April 1995). "The Outlaw Youngers: A Confederate Brotherhood". Madison Books. p. 408. ISBN 978-1568330457.

- Wellman Jr., Paul I; Brown, Richard Maxwell (April 1986). A Dynasty of Western Outlaws. University of Nebraska Press. p. 384. ISBN 978-0803297098.

- Younger, Cole (December 2012). The Story of Cole Younger, by Himself. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 158. ISBN 978-1481256131.

External links

- Works by Cole Younger at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Cole Younger at Internet Archive

- Works by Cole Younger at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Thomas Coleman "Cole" Younger". Post Civil War Outlaw. Find a Grave. January 1, 2001. Retrieved January 1, 2013.