Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar

| Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar | |

|---|---|

Cover art | |

| Developer(s) | Origin Systems |

| Publisher(s) |

Origin Systems Pony Canyon (Famicom) FCI (NES) Sega (SMS) |

| Designer(s) | Richard Garriott |

| Composer(s) |

Ken Arnold (home computers) Seiji Toda (NES) |

| Series | Ultima |

| Engine | Ultima IV Engine |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, Apple II, Atari 800, Atari ST, Commodore 64, DOS, FM Towns, MSX2, PC-88, PC-98, X68000, X1, FM-7, NES, Master System |

| Release date(s) |

September 16, 1985 1990 (NES, SMS) |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing video game |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar, first released in 1985[1] for the Apple II, is the fourth in the series of Ultima role-playing video games. It is the first in the "Age of Enlightenment" trilogy, shifting the series from the hack and slash, dungeon crawl gameplay of its "Age of Darkness" predecessors towards an ethically-nuanced, story-driven approach. In 1996 Computer Gaming World named Ultima IV as #2 on its Best Games of All Time list on the PC. Designer Richard Garriott considers this game to be among his favorites from the Ultima series.[2]

Plot

Ultima IV is among the few computer role-playing games, and perhaps the first, in which the game's story does not center on asking a player to overcome a tangible ultimate evil.[3]

After the defeat of each of the members of the triad of evil in the previous three Ultima games, the world of Sosaria underwent some radical changes in geography:[3] Three quarters of the world disappeared, continents rose and sank, and new cities were built to replace the ones that were lost. Eventually the world, now unified in Lord British's rule, was renamed Britannia. Lord British felt the people lacked purpose after their great struggles against the triad were over, and he was concerned with their spiritual well-being in this unfamiliar new age of relative peace, so he proclaimed the Quest of the Avatar: He needed someone to step forth and become the shining example for others to follow.

Unlike most other RPGs the game is not set in an "age of darkness"; prosperous Britannia resembles Renaissance Italy, or King Arthur's Camelot. The object of the game is to focus on the main character's development in virtuous life—possible because the land is at peace—and become a spiritual leader and an example to the people of the world of Britannia. The game follows the protagonist's struggle to understand and exercise the Eight Virtues.[4] After proving his or her understanding in each of the virtues, locating several artifacts and finally descending into the dungeon called the Stygian Abyss to gain access to the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom, the protagonist becomes an Avatar.

Conversely, actions in the game could remove a character's gained virtues, distancing them from the construction of truth, love, courage and the greater axiom of infinity—all required to complete the game. Though Avatarhood is not exclusive to one chosen person, the hero remains the only known Avatar throughout the later games, and as time passes he is increasingly regarded as a myth.

Gameplay

Instead of simply choosing stats to assign points to as in the first three Ultima games, you are instead asked various ethical dilemmas by a Gypsy using remotely tarot-like cards of the eight virtues. These situations do not have one correct resolution; rather, players must rank the eight virtues and whichever stands as their highest priority determines the type of character they will play. For example, choosing Compassion makes you a Bard, Honor a Paladin, Sacrifice a Tinker, and so on. This was also the first Ultima game where you had to play as a human, eliminating other races such as the elves, dwarves, and "bobbits" found in previous games altogether (however, even in the first three Ultimas where they could be chosen as player characters, there were never any non-player characters of those non-human races).

Although each profession embodies a particular virtue, to become an Avatar the player must achieve enlightenment in all eight virtues. Enlightenment in the virtues is achieved through the player's actions as well as through meditation at shrines. Shrines to each of the virtues are scattered about Britannia, each requiring the player to possess the corresponding virtue's Rune before allowing entry. Through meditation and correctly repeating the virtue's Mantra three times at the shrine, the player gains insight and ultimately enlightenment in the virtue. The seer Hawkwind in Lord British's castle provides the player with feedback on their progress in the virtues, offering advice for actions that will improve their virtue in each of the eight virtues, informing them when they are ready to visit a shrine for elevation, or chastising the character if they "hath strayed far from the path of the avatar". A player may be encouraged to give alms to the poor to improve their sacrifice, or never flee from battle to improve their honor. Players are equally able to lower their virtue by their in-game actions, such as stealing crops for food (lowering honesty) or selecting a bragging response in a dialogue with certain characters (lowers humility). While most actions have a minor effect on a virtue's progress, certain actions can have an immediate and devastating effect on a player's progress on multiple virtues, such as attacking an NPC while they sleep.

Technically, the game was very similar to Ultima III: Exodus, although much larger. This was the first Ultima game to feature a real conversation system—whereas NPCs in the earlier parts would only give one canned answer when talked to, now players could interact with them by specifying a subject of conversation, the subject determined either by a standard set of questions (name, job, health) or by information gleaned from the previous answers, or from other characters. Many sub-quests were arranged around this. Users playing the game a second time could save considerable time by knowing the answers to key questions which frequently required travel to another city to talk with another NPC. In at least one case, a player is asked "who sent you?", which may require yet another round trip between cities.

Another addition were dungeon rooms, uniquely designed combat areas in the dungeons which supplemented the standard combat against randomly appearing enemies.

Although Ultima IV was a turn-based game, the clock ran while the game was running. If a player didn't act for a while, NPCs and monsters may move and time would pass. Time was an important aspect to the game, as certain actions could only be performed at certain times.

The world of Britannia was first introduced here in full, and the world map in the series did not greatly change any more from this point onward. The player may travel about Britannia by foot, on horseback, across the sea in a ship or by air in a "lighter than air device". Speed and ease of travel is affected by the mode of travel as well as terrain and wind.

Virtues

The eight virtues of the Avatar, their relationship to the three principles of Truth, Love and Courage and how the gameplay has been designed around them are as follows:

- Honesty: Truth

When purchasing goods from blind merchants the player is required to enter the amount they actually wish to pay. Although the player has the option of paying less than the merchant has asked for, this will mark the player as dishonest. Stealing gold from chests owned by others (e.g. all chests found in towns, villages and castles) will also penalize the player. This Virtue is embodied by Mariah the Mage. - Compassion: Love

By using the Give conversation subject, a player can give beggars alms and in doing so demonstrate compassion. This Virtue is embodied by Iolo the Bard. - Valor: Courage

Valor is displayed by the player defeating enemies in combat and not fleeing in a cowardly fashion. This means that when retreat is necessary, the player should be the last party member to leave the field of battle. This Virtue is embodied by Geoffrey the Fighter. - Justice: Truth and Love

Not all of the hostile creatures in Britannia are evil and the player must avoid unprovoked attacks on those that are not. If attacked, he should resort to driving them away rather than killing them. Out of the eight virtues, this one requires the most finesse to embody and is a particularly good example of balancing ethical dilemmas. The player's party must stand their ground for Valor, yet drive their foes away without killing them. This Virtue is embodied by Jaana the Druid. - Honor: Truth and Courage

By completing quests (finding sacred items) and exploring dungeons the player demonstrates their honor. This Virtue is embodied by Dupre the Paladin. - Sacrifice: Love and Courage

If the player goes to a place of healing while in good health, the player can make a blood donation and sacrifice some health in doing so. This Virtue is embodied by Julia the Tinker. In the NES port she was replaced with a male character named Julius. - Spirituality: Truth, Love and Courage

Meditating at shrines, consulting the seer, and achieving enlightenment in the other virtues enhances the player's spirituality. This Virtue is embodied by Shamino the Ranger. - Humility: None, though it is considered the root of all virtue.

The player demonstrates their humility during conversations. A boastful response to a question results in a penalty, a humble response results in a bonus. This Virtue is embodied by Katrina the Shepherd.

Development

Richard Garriott has stated that he did not receive customer feedback for his first three games because neither California Pacific Computer nor Sierra On-Line forwarded him mail. After his own company released Ultima III, Garriott—who attended an interdenominational Christian Sunday School as a teenager—realized (partly from letters of enraged parents) that in the earlier games immoral actions like stealing and murder of peaceful citizens had been necessary or at least very useful actions in order to win the game, and that such features might be objectionable.[4] Garriott stated he wanted to become a good storyteller and make certain the story had content, and that 90% of the games out there, including his first three Ultima games, were what he called "go kill the evil bad guy" stories. He said that "Ultima IV was the first one that had ethical overtones in it, and it also was just a better told story."[5] Shay Addams, Garriott's official biographer, wrote "He decided that if people were going to look for hidden meaning in his work when they didn't even exist, he would introduce ideas and symbols with meaning and significance he deemed worthwhile, to give them something they could really think about."[6] Furthermore, organizations like BADD (Bothered About Dungeons and Dragons) were drawing attention to the supposedly satanic content in role-playing games in general, and the demonic nature of the antagonist of Ultima III, as depicted on that game's box cover, was a good target.

In retrospect, 1UP.com described Ultima IV as "a direct barb at the self-appointed moral crusaders who sought to demonize RPGs" and complained that "the irony in seeing an 'evil' RPG better present the Christian admonition to back faith with works in quiet modesty than the Bible-waving watchdog decrying the medium seems to have been lost".[7] Historian Jimmy Maher is skeptical that the post-Ultima III letters were as influential on Garriott's thinking as claimed, noting that he mentioned in a November 1983 interview—done almost immediately after the game's release—his plan to have the player in the next game acquire 16 virtues through "certain great deeds".[4]

The concept of virtues was inspired by a TV show about the Avatars of Hindu mythology, which described the avatars as having to master 16 different virtues. The eight virtues used in the game were derived from combinations of truth, love, and courage, a set of motivators Garriott found worked best, and also found in one of his favorite films, The Wizard of Oz. The game took two years to develop, twice that of both Ultima II and Ultima III. Garriott described the playtesting as "slightly rushed" to make the Christmas season; he was the only one to finish playing through the game by the time it went out for publishing.[8]

Like contemporary Origin games, Ultima IV was developed for the Apple II series then ported to other computers, partially because Garriott himself was an Apple II user/coder, partially because developing the games on there first made ports easier. Garriott said in 1984 that the Commodore 64 and Atari 8-bit's sprites and hardware sound chips made porting from them to Apple "far more difficult, perhaps even impossible ... the Apple version will never get done".[9] Like previous games, Ultima IV does not permit saving in dungeons because of technical limitations that Garriott described as "non-trivial".[8]

Versions

Apple II

Like previous Ultimas, Richard Garriott wrote most of the core code himself, however as the games were getting too complex for one person to handle, he was required to call in outside assistance for programming tasks he was not familiar with such as music and optimized disk routines. Ultima IV was the first game in the series to require a 64k Apple II and primarily targeted the newer Apple IIe and IIc, although it was still capable of running on an Apple II+ if a language card was used to boost the system to 64k (Garriott himself was still using a II+ at this time). Like it happened with Ultima III, Ultima IV also included support for the Mockingboard sound card, which enabled Apple II users to have 3-voice music. Custom disk routines allowed Ultima IV to have faster disk access than the previous games, which was also important as the growing size of the game caused it to now use two floppy disks instead of one.

The dialog of two NPCs in the Apple II release were accidentally not entered, leaving them in their default test states. One of these NPCs was the most elusive in the game, and provided the player with the final answer they would require to complete the game. With this character not responding properly, players were forced to guess the correct answer or find it from sources outside the game to complete it. This bug would later be acknowledged in Ultima V, where the NPC appears again and admits his mistake to the player.

Commodore 64

The C64 port was the first in the series to take full advantage of the computer's hardware rather than simply converting the sound and graphics from the Apple II, and include in-game music. It came on two 1541 disks and like the Apple II, Side 1 of Disk 1 (labeled "Program") was copy protected while the other disk sides ("Overworld", "Town", and "Dungeon") were not and the user was instructed to make backups of them. Ultima IV also added support for two disk drives, in which case the user would keep the Overworld side of Disk 1 in Drive 0 and flip the Town/Dungeon disk as needed in Drive 1. The Overworld disk is also used to load/save the player's progress. One of the biggest criticisms of the C64 port was a lack of any disk fastloader, which made for extremely slow disk access against the speed-optimized disk routines in the Apple version.

Atari 8-bit

Ultima IV was the final game in the series ported to the Atari 8-bit family. The game is still designed to support a 48k Atari 800 even though the 64k Atari 800XL had been out for almost two years as the installed userbase for the latter was much smaller. For similar reasons, the game was distributed on the 90k Atari 810 disk format, thus it occupies four disks instead of the two required for the Apple and Commodore versions. Because of memory constraints on the Atari 800, the Atari port does not have music.

PC compatible

Similar to the C64 port, the IBM version of Ultima IV, released two years after the 8-bit versions, takes proper advantage of the hardware for the first time instead of being a rushed conversion from the Apple II. EGA and Tandy graphics support is added, as well as proper hard disk support (the game finally supported DOS 2.x and subdirectories). However, there is no music in the IBM version even though the Tandy 1000 series had a 3-voice sound chip.

Amiga and Atari ST

The Atari ST version of Ultima IV was not released until 1987, the Amiga version not until 1988. Both are extremely similar to the PC port and do not fully utilize their machines' respective hardware features. In particular, the Amiga version has only 16-color graphics although the Amiga could display 32 on screen.

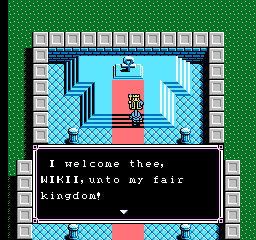

NES

Like Ultima III, Ultima IV was released to NES by FCI and Pony Canyon. This version, titled Ultima: Quest of the Avatar, was released in 1990.

The NES port of Ultima IV is very different from the other versions: the graphics had been completely redone, as was the music, and the dialogue options were greatly reduced. Among other gameplay changes, the player cannot have all seven recruitable characters in the player's party at the same time, as one could in other versions. Any character over the four the player could have would stay at a hostel at Castle Britannia, requiring the player to return there to change characters. However, the combat system was fairly close to the personal computer games, with the additional option to use automated combat. Additionally the spell-casting was simplified, removing the need to mix spells. Some puzzles were removed as well. This port also replaced the character Julia the Tinker with a male character named Julius. Some of these changes were done because of the memory limitations of being on a single cartridge instead of multiple floppy diskettes.

Master System

Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar for the Master System is the only Ultima to be ported to a Sega platform. It was released in 1990 and was both ported and published by Sega. The port features completely re-drawn graphics (although unlike the NES port, the style was retained from Origin's version), a simpler conversation system and, unlike the NES version, uses the regular Ultima IV background music. Although the Master System is easily capable of displaying more complex first-person scenes than those found in Ultima IV (see Phantasy Star), this version's dungeons are viewed from a top-down perspective, much like those of Ultima VI, which was released the same year. It seems that most of these cartridges were produced for the European market, as they contain a multi-lingual (English, French and German) manual, both books from the original version as well as a folded paper map. The books were of different colour for each of the three editions (blue for the UK version), fully translated and did not fit inside the game's box.

Ultima IV on modern operating systems

xu4 is a cross-platform game engine recreation of Ultima IV under development for Dreamcast, Linux, Mac OS X, RISC OS and Windows.[10]

Two other remakes were using the Neverwinter Nights engine.[11] An online version was written in Adobe Flash.[12] In March 2011, Electronic Arts sent a DMCA "cease and desist" notice to this fan project.[13] In 2015 also a fan-made remaster project was released with source code on GitHub, addressing bugs and improving other aspects of the game.[14][15]

Ultima IV is available for free through GOG.com.[16]

Sequel

Garriott stated in a 1985 interview that he was working on both Ultima IV: Part 2 and Ultima V.[8] Only Ultima V appeared.

Reception

Scorpia of Computer Gaming World in 1986 called it "an incredible game", only criticizing the fact that experience only came from combat, which the reviewer stated became "tedious". It concluded, "What are you waiting for? This will be a classic... go get it!!"[17] The game became the first to replace Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord—the top-rated adventure game for five years—in the magazine's reader poll,[18] and it named Ultima IV as the game of the year for 1986.[19] In 1987 Scorpia cited Ultima IV for taking the genre away from hack and slash; "for the first time, we have a CRPG whose focus IS character development. Not how many monsters you kill, nor how much loot you can pick up",[20] and in 1991 and 1993 she called it her favorite Ultima.[21][22] Dragon in 1986 called it "The most impressive and complex adventure to date; a total adventuring environment that takes place across an entire continent"[23] and the closest anyone has yet come to approximating a full-fledged fantasy role-playing experience in a computer game".[24] Famitsu reviewed the NES/Famicom version and scored it 31 out of 40.[25] In 2014 historian Jimmy Maher called Ultima IV a "transcendent masterwork" and estimated that the virtues influenced "hundreds of thousands of" players to live better lives, but criticized its "staggeringly difficult" nature and "pretty boring" gameplay, stating that without modern FAQs and walkthroughs, "it's honestly hard to imagine ... a kid who found it under the tree at Christmas 1985" or anyone else "solving it unaided". He concluded that the game "stands for me as a hugely important work in the history of its medium, but also one that hasn’t stood the test of time all that well. I love to think about it, love the fact that it exists, that Richard Garriott had the courage to make it — but just thinking about playing it makes me tired".[3]

Ultima IV was the top game on Billboard's list of software best sellers for February and March 1986.[26] Co-creator of D&D Dave Arneson in 1988 wrote that Ultima IV and a few other games "have stood pretty much alone as quirks instead of trend setters" in the CRPG industry, as other games did not follow their innovations.[27]

With a score of 7.80 out of 10, in 1988 Ultima IV was among the first members of the Computer Gaming World Hall of Fame for those games rated highly over time by readers.[28] In 1990 the game received the third-highest number of votes in a survey of readers' "All-Time Favorites".[29] In 1996, the magazine ranked it as the second-best video game of all time,[30] and the second most-innovative computer game.[31] In 2013, IGN placed Ultima IV at #26 in its list of top 100 RPGs of all time.[32] In 2015, Peter Tieryas of Tor.com stated that the NES version "represented a different type of ideal... You make up the narrative and you determine the course of your journey, engendering a sense of immersion that had the effect of making you feel like you were in more control than any previous RPG."[33]

See also

References

- ↑ (USCO# PA-317-504)

- ↑ Garriott, Richard. "Tabula Rasa Team Bios: Richard Garriott". NCSoft. Archived from the original on 2007-08-23. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- 1 2 3 Maher, Jimmy (2014-07-11). "Ultima IV". The Digital Antiquarian. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 Maher, Jimmy (2014-07-07). "The Road to IV". The Digital Antiquarian. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ http://www.uo.com/archive/ftp/text/intrview/richgar.txt

- ↑ The Official Book of Ultima by Shay Addams, page 39

- ↑ Parish, Jeremy (14 September 2012). "The Essential 100, No. 31: Ultima IV". 1UP.com. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Inside Ultima IV". Computer Gaming World. March 1986. pp. 18–21.

- ↑ "The CGW Computer Game Conference". Computer Gaming World (panel discussion). October 1984. p. 30.

- ↑ "Classic.1up.com's Essential 50: 21. Ultima IV". 1up.com. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ↑ The Ultima Reconstruction page

- ↑ Senior, Tom (2011-02-17). "Play Ultima 4 in your browser". PC Gamer. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ↑ "EA Uses DMCA Takedown on Ultima IV Downloads". GamePolitics. 2011-03-29. Retrieved 2012-06-01.

- ↑ Ultima IV Remastered v2.2.1 by Per Olofsson (29 May 2015)

- ↑ u4remastered on github.com

- ↑ Rossignol, Jim (2011-09-01). "Ultima IV Is Free On GoG Right Now". Rock Paper Shotgun. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- ↑ Scorpia (January–February 1986). "Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar". Computer Gaming World. p. 12. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ "Reader Input Device". Computer Gaming World. April 1986. p. 48. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ "Computer Gaming World Meets Dragoncon '87". Computer Gaming World. December 1987. p. 22. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ Scorpia (June–July 1987). "Computer Role-Playing Games / Now and Beyond". Computer Gaming World. p. 28. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ Scorpia (October 1991). "C*R*P*G*S / Computer Role-Playing Game Survey". Computer Gaming World. p. 16. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ Scorpia (October 1993). "Scorpia's Magic Scroll Of Games". Computer Gaming World. pp. 34–50. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ Lesser, Hartley and Pattie (June 1986). "The Role of Computers". Dragon (110): 38–43.

- ↑ Gray, Mike (September 1986). "Magic and morality". Dragon (113): 40–41.

- ↑ http://www.famitsu.com/cominy/?m=pc&a=page_h_title&title_id=19750

- ↑ "Hotware: Software Best Sellers". Compute!. June 1986. p. 102. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ Arneson, David L. (May 1988). "The Future of Computer Role-Playing". Computer Gaming World. p. 24. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "The CGW Hall of Fame". Computer Gaming World. March 1988. p. 44. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ "CGW Readers Select All-Time Favorites". Computer Gaming World. January 1990. p. 64. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. pp. 64–80. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "The 15 Most Innovative Computer Games". Computer Gaming World. November 1996. p. 102. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "Top 100 RPGs of All Time", IGN, 2013, retrieved 1 November 2013

- ↑ Tieryas, Peter. (March 2015). "What's the Point of an RPG Without a Main Villain? How Ultima IV Changed the Game". Tor.com.

- Kasavin, Greg & Soete, Tim (1998). "The Ultima Legacy". GameSpot.