Vilazodone

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Viibryd |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| MedlinePlus | a611020 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | N06AX24 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 72% (Oral, with food)[1] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic via CYP3A4[1] |

| Biological half-life | 25 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Faecal and renal[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

163521-12-8 |

| PubChem (CID) | 6918313 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 7427 |

| ChemSpider |

5293518 |

| UNII |

S239O2OOV3 |

| KEGG |

D09698 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:70707 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL439849 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

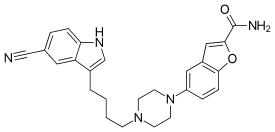

| Formula | C26H27N5O2 |

| Molar mass | 441.524 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Vilazodone (United States trade name Viibryd VEYE-brid) is a serotonergic antidepressant developed by Clinical Data for the treatment of major depressive disorder. The chemical compound was originally developed by Merck KGaA (Germany).[2] Vilazodone was approved by the FDA for use in the United States to treat major depressive disorder in 2011.[3][4][5] Its activity can be thought of as a combination of an SSRI and buspirone in some ways.

Medical uses

According to two eight-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in adults, vilazodone elicits an antidepressant response after one week of treatment. After eight weeks, subjects assigned to vilazodone 40 mg daily dose (titrated over two weeks) experienced a significantly higher response rate than the group given placebo (44% vs 30%, P = .002). Remission rates for vilazodone were not significantly different versus placebo.[6]

According to an article on the United States approval of vilazodone written by FDA staff, "it is unknown whether [vilazodone] has any advantages compared to other drugs in the antidepressant class."[7]

Adverse effects

After a one-year, open-label study assessing the safety and tolerability of vilazodone in people with major depressive disorder, the most common adverse effects were diarrhea (35.7%), nausea (31.6%), and headache (20.0%); greater than 90% of these adverse effects were mild or moderate.[6] Whereas in randomized controlled trials these rates were 28%, 23.4% and 13.3%, respectively.[6] In contrast to other SSRIs currently on the market, initial clinical trials showed that vilazodone did not cause significant decreased sexual desire/function as with many other antidepressants, which often cause people to abandon their use.[3]

Incidence of adverse effects

Incidence of adverse effects include:[1]

- Very common adverse effects (incidence >10%)

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Headache

- Common adverse effects (1-10% incidence)

- Vomiting

- Dry mouth

- Dizziness

- Insomnia

- Uncommon adverse effects (0.1-1% incidence)

- Somnolence

- Paraesthesia

- Tremor

- Abnormal dreams

- Libido decreased

- Restlessness

- Akathisia

- Restless legs syndrome

- Abnormal orgasms (male persons only)

- Delayed ejaculations (male persons only)

- Erectile dysfunction (male persons only)

- Fatigue

- Feeling jittery

- Palpitations

- Ventricular premature contractions

- Arthralgia

- Increased appetite

- Rare adverse effects (<0.1% incidence)

- Serotonin syndrome — a serious adverse effect characterised by:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Mental status change (e.g. confusion, hallucinations, agitation, coma, stupor)

- Muscle rigidity

- Tremor

- Myoclonus

- Hyperreflexia — overresponsive/overactive reflexes

- Hyperthermia — elevated body temperature

- Autonomic instability (e.g. tachycardia, dizziness, abnormally excessive sweating, etc.)

- Mania/hypomania — a potentially dangerously elated/agitated mood. Every antidepressant has the potential to induce these psychiatric reactions. They are particularly problematic in those with a history of hypomania/mania such as those with bipolar disorder.[8]

- Unknown-incidence adverse effects

- Suicidal ideation — all antidepressants can cause suicidal ideation especially in young adults and adolescents under the age of 25.

- Abnormal bleeding — the SSRIs are known for their ability to increase the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeds and other bleeding abnormalities.[8][9][10]

- Seizures

- Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) — a condition characterised by an abnormally excessive secretion of antidiuretic hormone causing potentially-fatal electrolyte abnormalities (such as hyponatraemia).

- Hyponatraemia (a complication of the former) — low blood sodium.

Pharmacology

Vilazodone acts as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor (IC50 = 2.1 nM; Ki = 0.1 nM) and 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist (IC50 = 0.2 nM; IA = ~60–70%).[6][11] It has negligible affinity for other serotonin receptors such as 5-HT1D, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT2C.[11][12] It also exhibits negligible inhibitory activity at the norepinephrine and dopamine transporters (IC50 = 56 nM for NET and 37 nM for DAT).[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "VIIBRYD (vilazodone hydrochloride) tablet VIIBRYD (vilazodone hydrochloride) kit [Forest Laboratories, Inc.]". DailyMed. Forest Laboratories, Inc. December 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ↑ "Clinical Data's Vilazodone Patient Enrollment Over One Third Complete". Business Wire. Berkshire Hathaway. 17 August 2006. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- 1 2 "FDA approves Clinical Data Inc's antidepressant". Reuters. January 22, 2011.

- ↑ "FDA approves Clinical Data Inc's antidepressant". Reuters. January 22, 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ↑ "Clinical Data, Inc. - Clinical Data, Inc. Submits New Drug Application for Vilazodone for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder". Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Wang, SM; Han, C; Lee, SJ; Patkar, AA; Masand, PS; Pae, CU (August 2013). "A review of current evidence for vilazodone in major depressive disorder.". International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 17 (3): 160–9. doi:10.3109/13651501.2013.794245. PMID 23578403.

- ↑ Laughren TP, Gobburu J, Temple RJ, Unger EF, Bhattaram A, Dinh PV, Fossom L, Hung HM, Klimek V, Lee JE, Levin RL, Lindberg CY, Mathis M, Rosloff BN, Wang SJ, Wang Y, Yang P, Yu B, Zhang H, Zhang L, Zineh I (September 2011). "Vilazodone: clinical basis for the US Food and Drug Administration's approval of a new antidepressant". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 72 (9): 1166–73. doi:10.4088/JCP.11r06984. PMID 21951984.

- 1 2 Australian Medicines Handbook 2013. The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust; 2013.

- ↑ Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S, Taylor D. The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. 11th ed. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2012.

- ↑ Wang Y-P, Chen Y-T, Tsai C-F, Li S-Y, Luo J-C, Wang S-J, et al. Short-Term Use of Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Risk of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Am J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2013 Sep 13 [cited 2013 Oct 6]; Available from: http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleid=1738031

- 1 2 Hughes ZA, Starr KR, Langmead CJ, et al. (March 2005). "Neurochemical evaluation of the novel 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist/serotonin reuptake inhibitor, vilazodone". European Journal of Pharmacology. 510 (1–2): 49–57. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.01.018. PMID 15740724.

- ↑ Page ME, Cryan JF, Sullivan A, et al. (September 2002). "Behavioral and neurochemical effects of 5-(4-[4-(5-Cyano-3-indolyl)-butyl)-butyl]-1-piperazinyl)-benzofuran-2-carboxamide (EMD 68843): a combined selective inhibitor of serotonin reuptake and 5-hydroxytryptamine(1A) receptor partial agonist". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 302 (3): 1220–7. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.034280. PMID 12183683.