Circle packing

- This article describes the packing of circles on surfaces. For the related article on circle packing with a prescribed intersection graph, please see the circle packing theorem.

In geometry, circle packing is the study of the arrangement of circles (of equal or varying sizes) on a given surface such that no overlapping occurs and so that all circles touch one another. The associated packing density, η, of an arrangement is the proportion of the surface covered by the circles. Generalisations can be made to higher dimensions – this is called sphere packing, which usually deals only with identical spheres.

While the circle has a relatively low maximum packing density of 0.9069 on the Euclidean plane, it does not have the lowest possible. The "worst" shape to pack onto a plane is not known, but the smoothed octagon has a packing density of about 0.902414, which is the lowest maximum packing density known of any centrally-symmetric convex shape.[1] Packing densities of concave shapes such as star polygons can be arbitrarily small.

The branch of mathematics generally known as "circle packing" is concerned with the geometry and combinatorics of packings of arbitrarily-sized circles: these give rise to discrete analogs of conformal mapping, Riemann surfaces and the like.

Packings in the plane

.svg.png)

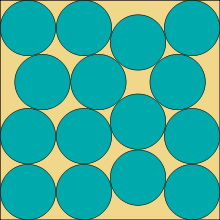

In two dimensional Euclidean space, Joseph Louis Lagrange proved in 1773 that the highest-density lattice arrangement of circles is the hexagonal packing arrangement,[2] in which the centres of the circles are arranged in a hexagonal lattice (staggered rows, like a honeycomb), and each circle is surrounded by 6 other circles. The density of this arrangement is

Axel Thue provided the first proof that this was optimal in 1890, showing that the hexagonal lattice is the densest of all possible circle packings, both regular and irregular. However, his proof was considered by some to be incomplete. The first rigorous proof is attributed to László Fejes Tóth in 1940.[2]

At the other extreme, very low density arrangements of rigidly packed circles have been identified.

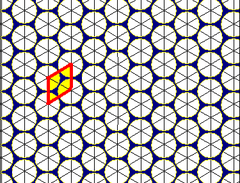

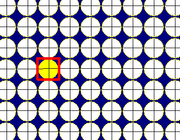

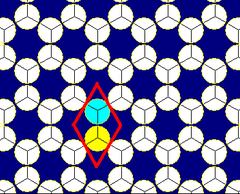

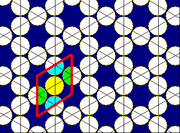

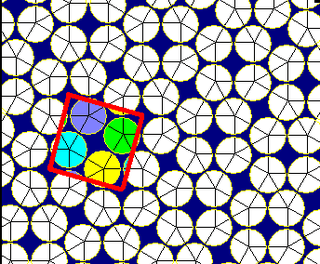

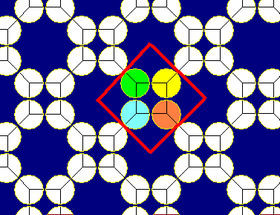

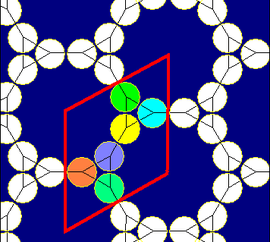

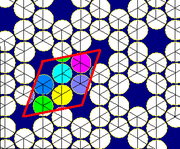

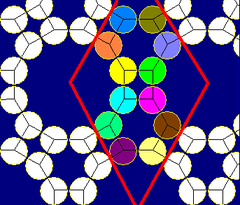

Uniform packings

There are 11 circle packings based on the 11 uniform tilings of the plane.[3] In these packings, every circle can be mapped to every other circle by reflections and rotations. The hexagonal gaps can be filled by one circle and the dodecagonal gaps can be filled with 7 circles, creating 3-uniform packings. The truncated trihexagonal tiling with both types of gaps can be filled as a 4-uniform packing. The snub hexagonal tiling has two mirror-image forms.

Triangular |

Square |

Hexagonal |

Elongated triangular |

Trihexagonal |

Snub square |

Truncated square |

Truncated hexagonal |

Rhombitrihexagonal |

Snub hexagonal |

Snub hexagonal (mirrored) |

Truncated trihexagonal |

Packings on the sphere

A related problem is to determine the lowest-energy arrangement of identically interacting points that are constrained to lie within a given surface. The Thomson problem deals with the lowest energy distribution of identical electric charges on the surface of a sphere. The Tammes problem is a generalisation of this, dealing with maximising the minimum distance between circles on sphere. This is analogous to distributing non-point charges on a sphere.

Packings in bounded areas

Packing circles in simple bounded shapes is a common type of problem in recreational mathematics. The influence of the container walls is important, and hexagonal packing is generally not optimal for small numbers of circles.

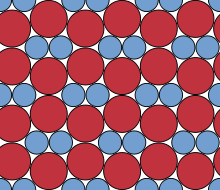

Unequal circles

There are also a range of problems which permit the sizes of the circles to be non-uniform. One such extension is to find the maximum possible density of a system with two specific sizes of circle (a binary system). Only nine particular radius ratios permit compact packing, which is when every pair of circles in contact is in mutual contact with two other circles (when line segments are drawn from contacting circle-center to circle-center, they triangulate the surface).[4] For seven of these radius ratios a compact packing is known that achieves the maximum possible packing fraction (above that of uniformly-sized discs) for mixtures of discs with that radius ratio. The highest packing density is 0.911627478 for a radius ratio of 0.545151042·[5][6]

It is also known that if the radius ratio is above 0.742, a binary mixture cannot pack better than uniformly-sized discs.[5] Upper bounds for the density that can be obtained in such binary packings at smaller ratios have also been obtained.[7]

Applications of circle packing

Quadrature amplitude modulation is based on packing circles into circles within a phase-amplitude space. A modem transmits data as a series of points in a 2-dimensional phase-amplitude plane. The spacing between the points determines the noise tolerance of the transmission, while the circumscribing circle diameter determines the transmitter power required. Performance is maximized when the constellation of code points are at the centres of an efficient circle packing. In practice, suboptimal rectangular packings are often used to simplify decoding.

Circle packing has become an essential tool in origami design, as each appendage on an origami figure requires a circle of paper.[8] Robert J. Lang has used the mathematics of circle packing to develop computer programs that aid in the design of complex origami figures.

See also

- Apollonian gasket

- Circle packing in a square

- Circle packing in a circle

- Inversive distance

- Kepler conjecture

- Malfatti circles

- Packing problem

Bibliography

- Wells D (1991). The Penguin Dictionary of Curious and Interesting Geometry. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 30–31, 167. ISBN 0-14-011813-6.

- Stephenson, Kenneth (December 2003). "Circle Packing: A Mathematical Tale" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. 50 (11).

References

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W. "Smoothed Octagon". MathWorld.

- 1 2 Chang, Hai-Chau; Wang, Lih-Chung (2010). "A Simple Proof of Thue's Theorem on Circle Packing". arXiv:1009.4322

[math.MG].

[math.MG]. - ↑ Williams, Robert (1979). The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure: A Source Book of Design. Dover Publications, Inc. p. 35-39. ISBN 0-486-23729-X.

- 1 2 Tom Kennedy (2006). "Compact packings of the plane with two sizes of discs". Discrete and Computational Geometry. 35 (2): 255–267. arXiv:math/0407145v2

. doi:10.1007/s00454-005-1172-4.

. doi:10.1007/s00454-005-1172-4. - 1 2 3 Heppes, Aladár (1 August 2003). "Some Densest Two-Size Disc Packings in the Plane". Discrete and Computational Geometry. 30 (2): 241–262. doi:10.1007/s00454-003-0007-6.

- ↑ Kennedy, Tom (21 Dec 2004). "A densest compact planar packing with two sizes of discs". Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ↑ de Laat, David; de Oliveira Filho, Fernando Mario; Vallentin, Frank (12 June 2012). "Upper bounds for packings of spheres of several radii". arXiv:1206.2608

.

. - ↑ TED.com lecture on modern origami "Robert Lang on TED."