Dominant seventh chord

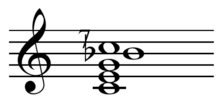

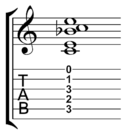

In music theory, a dominant seventh chord, or major minor seventh chord,[lower-alpha 1] is a chord composed of a root, major third, perfect fifth, and minor seventh. It can be also viewed as a major triad with an additional minor seventh. When using popular-music symbols, it is denoted by adding a superscript "7" after the letter designating the chord root.[1] The dominant seventh is found almost as often as the dominant triad.[2] In Roman numerals it is represented as V7. The chord can be represented by the integer notation {0, 4, 7, 10}.

| Component intervals from root | |

|---|---|

| minor seventh | |

| perfect fifth | |

| major third | |

| root | |

| Tuning | |

| 4:5:6:7[3] | |

| Forte no. / | |

|

4-27 / |

Of all the seventh chords, perhaps the most important is the dominant seventh. It was the first seventh chord to appear regularly in classical music. The name comes from the fact that it occurs naturally in the seventh chord built upon the dominant (i.e., the fifth degree) of a given major diatonic scale. Take for example the C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C):

The note G is the dominant degree of C major—its fifth note. When we arrange the notes of the C major scale in ascending pitch and use only these notes to build a seventh chord, and we start with G (not C), then the resulting chord contains the four notes G–B–D–F and is called G dominant seventh (G7). The note F is a minor seventh from G, and it is also called the dominant seventh with respect to G.

Function

The function of the dominant seventh chord is to drive to or resolve to the tonic note or chord.

... the demand of the V7 for resolution is, to our ears, almost inescapably compelling. The dominant seventh is, in fact, the central propulsive force in our music; it is unambiguous and unequivocal.— Goldman, (1965: 35)[5]

This basic dominant seventh chord is useful to composers because it contains both a major triad and the interval of a tritone. The major triad confers a very "strong" sound. The tritone is created by the co-occurrence of the third degree and seventh degree (e.g., in the G7 chord, the acoustic distance between B and F is a tritone). In a diatonic context, the third of the chord is the leading-tone of the scale, which has a strong tendency to pull towards the tonal center, or root note, of the key (e.g., in C, the third of G7, B, is the leading tone of the key of C). The seventh of the chord acts as an upper leading-tone to the third of the scale (in C: the seventh of G7, F, is a half-step above and leads down to E).[5] This, in combination with the strength of root movement by fifth, and the natural resolution of the dominant triad to the tonic triad (e.g., from GBD to CEG in the key of C major), creates a resolution with which to end a piece or a section of a piece. Because of this original usage, it also quickly became an easy way to trick the listener's ear with a deceptive cadence. The dominant seventh may work as part of a circle progression, preceded by the supertonic.

In rock and popular music songs following, "the blues harmonic pattern," IV and V are, "almost always," major minor seventh chords, or extensions, with the tonic most often being a major triad, for example Bill Haley and the Comets' "Rock Around The Clock" and Buster Brown's "Fanny Mae", while in Chuck Berry's "Back in the U.S.A." and Loggins and Messina's "Your Mama Don't Dance" the tonic is also a major minor seventh.[7] Used mostly in the first fifteen years of the rock era and now sounding somewhat, "retrospective," (Oasis' "Roll With It") other examples of tonic dominant seventh chords include Little Richard's "Lucille", the Beatles' "I Saw Her Standing There", Nilsson's "Coconut", Jim Croce's "You Don't Mess Around With Jim", and the Drifters' "On Broadway".[7] Chuck Berry's "Rock And Roll Music" uses the dominant seventh on I, IV, and V.[8] See: Twelve-bar blues.

Chromatic seventh

However, the most important use of the dominant seventh chord in musical composition is the way that the introduction of a non-diatonic dominant seventh chord (sometimes called a chromatic seventh), which is borrowed from another key, can allow the composer to modulate to that other key. This technique is extremely common, particularly since the classical period, and has led to further innovative uses of the dominant seventh chord such as secondary dominant (V7/V), extended dominant (V/V/V), and substitute dominant (♭V7/V) chords.

German sixth

The dominant seventh is enharmonically equivalent to the German sixth, causing the chords to be spelled enharmonically, for example the German sixth G♭–B♭–D♭–E and the dominant seventh F♯–A♯–C♯–E.[9]

Harmonic seventh

The dominant seventh is frequently used to approximate a Harmonic seventh chord, which is one possible just tuning, in the ratios 4:5:6:7[3] ![]() Play , for the dominant seventh. Others include 20:25:30:36

Play , for the dominant seventh. Others include 20:25:30:36 ![]() Play , found on I, and 36:45:54:64, found on V, used in 5-limit just tunings and scales.[10]

Play , found on I, and 36:45:54:64, found on V, used in 5-limit just tunings and scales.[10]

History

Renaissance composers decided in terms of intervals rather than chords, "however, certain dissonant sonorities suggest that the dominant seventh chord occurred with some frequency." Monteverdi (usually credited as the first to use the V7 chord without preparation[13]) and other early baroque composers begin to treat the V7 as a chord as part of the introduction of functional harmony. The V7 was in constant use during the classical period, with similar treatment to that of the baroque. In the romantic period freer voice-leading was gradually developed, leading to the waning of functional use in the post-romantic and impressionistic periods including more dissonant dominant chords through higher extensions and lessened use of the major-minor chord's dominant function. 20th century music either consciously used functional harmony or was entirely free of V7 chords while jazz and popular musics continued to use functional harmony including V7 chords.[11]

However, according to Schenker, "'The dissonance is always passing, never a chord member (Zusammenklang),'"[14] and often (though by no means always) the voice leading suggests either a passing note:

8 7 3 5 5 1

or resolution of a (hypothetical) suspension:

(8) 7 3 (4) 5 1

Today, the dominant seventh chord enjoys particular prominence in the music of barbershop quartets, with the Barbershop Harmony Society specifying that a song must use the chord type (built on any scale degree, not just the dominant) for 35 to 60 percent of its duration to be considered "true barbershop" (i.e., eligible for use in competitions). As barbershop singers strive to harmonize in just intonation to maximize the audibility of harmonic overtones, the practical sonority of the chord tends to be that of an harmonic seventh chord. This chord type has become so ingrained into the fabric of the artform that it is often referred to as the "barbershop seventh chord" by those who practice it.

Voice leading

For common practice voice leading, or "strict resolution" of the dominant seventh chord:[15]

- In the V7–I resolution, the dominant, leading note, and supertonic resolve to the tonic, whereas the subdominant resolves to the mediant.

- In the other resolutions, the dominant remains stationary, the leading note and supertonic resolve to the tonic, and the subdominant resolves to the mediant.

- All four tones may be present, though the root may be doubled and the fifth omitted.[15][16][17]

- The d5 resolves inwards and the A4 resolves outwards, meaning that the seventh resolves stepwise downwards[16][17] while the third resolves (stepwise upwards) to the tonic[15] though in such cases the root of the tonic chord may need to be tripled.[16]

- The root of the V7, when in the bass, resolves to the root of the I, in the bass.[15]

- In an incomplete V7, with a missing fifth, the doubled root remains stationary.[15]

- The "free resolution of the seventh" features the seventh in an inner voice moving stepwise upwards to the fifth of I[15]

Tuning

| Chord | Notation | Seventh | Ratios |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tonic seventh chord | C E G B♭ | Minor seventh | 20:25:30:36[18][10] |

| Harmonic seventh chord | G B D F | Harmonic seventh | 4:5:6:7[3] |

| German sixth chord | A♭ C E♭ G | Harmonic seventh | 4:5:6:7 |

| Dominant seventh chord | G B D F | Pythagorean minor seventh | 36:45:54:64[10] |

Dominant seventh chord table

| Chord | Root | Major Third | Perfect Fifth | Minor Seventh |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C7 | C | E | G | B♭ |

| C♯7 | C♯ | E♯ (F) | G♯ | B |

| D♭7 | D♭ | F | A♭ | C♭ (B) |

| D7 | D | F♯ | A | C |

| D♯7 | D♯ | F |

A♯ | C♯ |

| E♭7 | E♭ | G | B♭ | D♭ |

| E7 | E | G♯ | B | D |

| F7 | F | A | C | E♭ |

| F♯7 | F♯ | A♯ | C♯ | E |

| G♭7 | G♭ | B♭ | D♭ | F♭ (E) |

| G7 | G | B | D | F |

| G♯7 | G♯ | B♯ (C) | D♯ | F♯ |

| A♭7 | A♭ | C | E♭ | G♭ |

| A7 | A | C♯ | E | G |

| A♯7 | A♯ | C |

E♯ (F) | G♯ |

| B♭7 | B♭ | D | F | A♭ |

| B7 | B | D♯ | F♯ | A |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Also written major-minor seventh chord.

Sources

- ↑ Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p. 77. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ↑ Benward & Saker (2003), p. 199.

- 1 2 3 Benitez, J. M. (1988). Contemporary Music Review: Listening 2, p. 34. ISBN 3-7186-4846-6. Cites Euler (1764).

- ↑ Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony in Concept & Practice, p. 145. Third edition. ISBN 0-03-020756-8.

- 1 2 Goldman, Richard Franco (1965), Harmony in Western Music, pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-214-66680-8.

- ↑ Benward & Saker (2003), p.202.

- 1 2 Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis, p. 82. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

- ↑ Stephenson (2002), p. 75.

- ↑ Benward & Saker (2008). Music in Theory and Practice, Vol. II, p. 222. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- 1 2 3 Wright, David (2009). Mathematics and Music, pp. 140–41. ISBN 978-0-8218-4873-9.

- 1 2 3 Benward & Saker (2003), p.201.

- ↑ Forte (1979), p.142.

- ↑ Goldman (1965), p. 39.

- ↑ Schenker, Heinrich. Jahrbuch II, p. 24 cited in Jonas, Oswald (1982). Introduction to the Theory of Heinrich Schenker (1934: Das Wesen des musikalischen Kunstwerks: Eine Einführung in Die Lehre Heinrich Schenkers), p. 20. Trans. John Rothgeb. ISBN 0-582-28227-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Benjamin, Horvit, and Nelson (2008). Techniques and Materials of Music, pp. 46–47. ISBN 0-495-50054-2.

- 1 2 3 Benward & Saker (2003), pp. 202–204.

- 1 2 Benward & Saker (2008), p. 343

- ↑ Shirlaw, Matthew (1900). The Theory of Harmony, p. 86. ISBN 978-1-4510-1534-8.