Eleventh chord

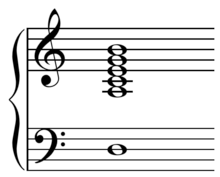

In music theory, an eleventh chord is a chord that contains the tertian extension of the eleventh. Typically found in jazz, an eleventh chord also usually includes the seventh and ninth, and elements of the basic triad structure. Variants include the dominant eleventh, minor eleventh, and the major eleventh chord. Symbols include: Caug11, C9(aug11), C9(+11), C9alt11, Cmin9(11), C-(9)(11).[3] The eleventh in an eleventh chord is, "almost always sharped, especially in jazz,"[4] at least in reference to the third, with CM11 (major eleventh): C-E-G-B-D-F♯, Cm11 (minor eleventh): C-E♭-G-B♭-D-F, and C11 (dominant eleventh): C-E-G-B♭-D-F.[4]

However, since the major diatonic eleventh would create a dissonant minor ninth interval with the third of the chord, including the third is a rare phenomenon, even in 20th-century classical music. Though rare, in rock and popular music, for example 52 seconds into "Sun King" on the Beatles' Abbey Road, the third of the dominant eleventh ("as theoretically conceived": C, E, G, B♭, D, F ![]() play ), for example, is usually omitted.[1] It may be notated in charts as, C11, or, more often, "descriptively," as Gm7/C.[1] The fifth is also sometimes omitted, thus turning the chord into a suspended chord (C, B♭, D, F).

play ), for example, is usually omitted.[1] It may be notated in charts as, C11, or, more often, "descriptively," as Gm7/C.[1] The fifth is also sometimes omitted, thus turning the chord into a suspended chord (C, B♭, D, F).

As the upper extensions (7th, 9th, 11th) constitute a triad, a dominant eleventh chord with the 3rd and 5th omitted is often notated as a triad with a bass note. So C-B♭-D-F is written as B♭/C, emphasizing the ambiguous dominant/subdominant character of this voicing.

In the dominant eleventh, because this minor ninth interval between the third and the eleventh is more problematic to the ear and to voice leading than a major ninth would be, alterations to the third or eleventh scale degrees are a common solution. When the third is lowered, a minor eleventh chord is formed with a major ninth interval between the two notes in question (e.g. C, E♭, G, B♭, D, F) ![]() play .[4] Similarly, the eleventh may be raised chromatically over a major triad (e.g. to F♯ in a C major chord) to imply the lydian dominant mode. A less common solution to the issue is to simply omit the third in the presence of the eleventh, resulting in a chord enharmonic to the suspended chord (sus4). This type of chord should be notated as such.

play .[4] Similarly, the eleventh may be raised chromatically over a major triad (e.g. to F♯ in a C major chord) to imply the lydian dominant mode. A less common solution to the issue is to simply omit the third in the presence of the eleventh, resulting in a chord enharmonic to the suspended chord (sus4). This type of chord should be notated as such.

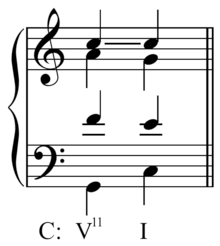

In the common practice period, "the root, 7th, 9th, and 11th are the most common factors present in the V11 chord," with the 3rd and 5th, "typically omitted".[6] The 11th is usually retained as a common tone when the, "V11 resolves to I or i".[6]

The suspended chord derived from the dominant eleventh chord (with the third omitted and the seventh flattened), is particularly useful in diatonic music when a composer or accompanist wishes to allow the tonic note of a key to be heard while also sounding the dominant of that key in the bass.

Fourth

The fourth factor of a chord is the note or pitch four scale degrees above the root or tonal center. When the fourth is the bass note, or lowest note, of the expressed chord, the chord is in first inversion ![]() Play . However, this is equivalent to a gapped ninth chord.

Play . However, this is equivalent to a gapped ninth chord.

Conventionally, the fourth is third in importance to the root, fifth, and third, being an added tone. It may be avoided as the root since that inversion may resembles a ninth chord on the fourth rather than a suspended chord on the original note. In jazz chords and theory, the fourth is required due to its being an added tone.

The quality of the fourth may be determined by the scale or may be indicated. For example, in both a major and minor scale, a diatonic fourth added to the tonic chord is major (C-F-G)—while one added to the subdominant chord is major or minor (F-B-C or F-B♭-C), respectively.

The fourth is octave equivalent to the eleventh. If one could cut out the notes in between the fifth and the eleventh and then drop the eleventh down an octave to a fourth, one would have a fourth chord (CEGB♭D′F′ – B♭D′ = CEFG). The difference between sus4 and add11 is conventionally the absence or presence, respectively, of the third.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis, p.87. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

- ↑ Kernfeld, Barry (1997). What to Listen for in Jazz, p.68. ISBN 978-0-300-07259-4.

- ↑ Smith, Johnny (1980). Mel Bay's Complete Johnny Smith Approach to Guitar, p.231. ISBN 978-1-56222-239-0.

- 1 2 3 Miller, Michael (2004). Complete Idiot's Guide to Solos and Improvisation, p.52. ISBN 978-1-59257-210-6.

- ↑ Kostka & Payne (1995). Tonal Harmony, p.431. Third Edition. ISBN 0-07-300056-6.

- 1 2 3 Benward & Saker (2009). Music in Theory and Practice: Volume II, p.183-84. Eighth Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- ↑ Hawkins, Stan. "Prince- Harmonic Analysis of 'Anna Stesia'", p.329 and 334n7, Popular Music, Vol. 11, No. 3 (Oct., 1992), pp. 325-335.