Extended chord

In music, extended chords are tertian chords (built from thirds) or triads with notes extended, or added, beyond the seventh. Ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth chords are extended chords. The thirteenth is the farthest extension diatonically possible as, by that point, all seven tonal degrees are represented within the chord. In practice however, extended chords do not typically use all the chord members; when it is not altered, the fifth is often omitted, as are notes between the seventh and the highest note (i.e., the ninth is often omitted in an eleventh chord; the ninth and eleventh are usually omitted in a thirteenth chord), unless they are altered to give a special texture. See chord alteration.

Chords extended beyond the seventh are rarely seen in the Baroque era, and are used more frequently in the Classical era. The Romantic era saw greatly increased use of extended harmony. Extended harmony prior to the 20th century usually has dominant function – as V9, V11, and V13, or V9/V, V13/ii etc.

Examples of the extended chords used as tonic harmonies include Wild Cherry's "Play That Funky Music" (either a dominant ninth or dominant thirteenth).[2]

Common practice period

During the Common practice period of Classical music, composers orchestrating chords that are voiced in four or fewer parts would select which notes to use so as to give the desired sonority, or effect of the intended chord. Generally, priority was given to the third, seventh and the most extended tone, as these factors most strongly influence the quality and function of the chord. The root is never omitted from the texture. The third defines the chord's quality as major or minor. The extended note defines the quality of the extended pitch, which may be major, minor, perfect, or augmented. The seventh factor helps to define the chord as an extended chord (and not an added note chord), and also adds to the texture. Any notes which happen to be altered, such as a flatted fifth or ninth, should also be given priority. For example: in a thirteenth chord, one would play the root, third, seventh, and thirteenth, and be able to leave out the fifth, ninth, and eleventh without affecting the function of the chord. The eleventh chord is an exception to this voicing, in which the root, seventh, ninth, and eleventh are most commonly used.

In the classical practices of western music, extended chords most often have dominant function (dominant or secondary dominant), and will resolve in circle progression (down a fifth) in much the same way that V7, V7/ii, V/IV, etc. might resolve to their respective tonics. Extended chords can also be altered dominants, and the extended pitch may be altered in several ways (such as V flat 13 in a major key).

Following standard voice leading rules:

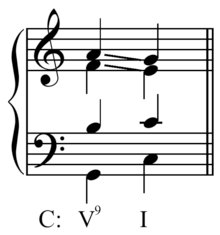

V9 – I or i

- The third, which will also be the seventh scale degree, always resolves upward to tonic.

- The seventh resolves downwards stepwise to the third factor of the chord of resolution.

- The extended pitch will resolve downward.

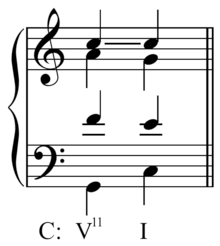

V11 – I or i

- The seventh resolves downwards stepwise to the third factor of the chord of resolution.

- The ninth resolves downwards stepwise to the fifth factor of the chord of resolution.

- The eleventh doesn't move, and becomes the root of the chord of resolution.

V13 – I or i

- The seventh resolves downwards stepwise to the third factor of the chord of resolution.

- The third, which will also be the seventh scale degree, always resolves upward to tonic.

- The thirteenth, will resolve downward to the tonic, and often includes a passing tone through the ninth factor of the chord of resolution. Less often, the thirteenth may also remain the same and become the third of the chord of resolution.

An important distinction between Extended and Added chords must be made, since the added tones and extended tones are enharmonic, but differ in function. Extended chords always have at least one octave between their lowest pitch, and extended note, otherwise the extended factor would be considered an added pitch. Extended chords usually must be resolved when used in a dominant function, whereas added chords are most often textures added to a tonic.

History

18th century

In the 18th-century 9th and 11th chords were theorized as downward extensions of 7th chords, according to theories of supposition.[5]

In 1722 Rameau first proposed the concept that 9th and 11th chords are built from seventh chords by (the composer) placing a "supposed" bass one or two thirds below the fundamental bass or actual root of the chord.[6] With the theoretical chord F A C E G B the fundamental bass would be considered C, while the supposed bass would be F.[6] Thus the notes F and A are added below a seventh chord on C, C E G B, triadically (in thirds). This is also referred to as the "H chord".

The theory of supposition was adopted and modified by Roussier, Marpurg, and other theorists. A. F. C. Kollmann, following Kirnberger, adopted a simpler approach and one closer to that prevalent today, in which Rameau's "supposed" bass is considered the fundamental and the 9th and 11th are regarded as transient notes inessential to the structure of the chord.[6] Thus F A C E G B is considered a seventh chord on F, F A C E, with G and B being nonchord tones added above triadically.

19th century

In 19th-century classical music the seventh chord was generally the upper limit in "chordal consonance", with 9th and 11th chords being used for "extra power" but invariably with one or more notes treated as appoggiaturas.[5] The thickness of complete 9th, 11th, or 13th chords in close position was also generally avoided through leaving out one or more tones or using wider spacing (open position).[5]

20th century

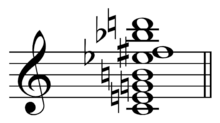

In the 20th century, especially in jazz and popular music, 9th chords were used as elaborations of simpler chords, particularly as substitutes for the tonic triad at the end of a piece.[5] The "piling up" of thirds above the tonic to make 7th, 9th, 11th, or even 13th chords "is one of the most important characteristics of jazz harmony".[5] Vítězslav Novák student, Jaroslav Novotný (1886-1918) used a fifteenth chord in the fourth song of his 1909 song cycle Eternal Marriage.[8]

Chord structure

Building on each of the major scale degrees the 13th chord chord quality that is harmonic to such scale (i.e. with all its notes belonging to such scale), results in the following table. The numbering is relative to the scale degree numbers of the major scale that has the major scale degree in question as tonic:

| Chord Root | Chord Quality | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | maj13 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ii | m13 | - | ♭ | - | ♭ | - | - | - |

| iii | m7♭9♭13 | - | ♭ | - | ♭ | ♭ | - | ♭ |

| IV | maj13♯11 | - | - | - | - | - | ♯ | - |

| V | 13 | - | - | - | ♭ | - | - | - |

| vi | m7♭13 | - | ♭ | - | ♭ | - | - | ♭ |

| viio | 7ø♭9♭13 | - | ♭ | ♭ | ♭ | ♭ | - | ♭ |

Other 13th chord qualities do exist but they do not belong to any scale mode.

From the table it is clear that adding an 11th or a 13th makes the seven chord qualities distinguishable from each other, as without an 11th added the I and IV chord quality would be identical, and without a 13th added the ii and vi chord quality would be identical.

Jazz, jazz fusion and funk

Jazz from the 1930s onward, jazz fusion from the 1970s and onward and funk all use extended chords as a key part of their sound. In these genres, chords often include added ninths, elevenths and thirteenths and altered variants, such as flat ninths, sharp ninths, sharp 11ths and flat 13ths. In jazz and jazz fusion, songs consist of complex chord progressions in which many of the chords are extended chords and in which many of the dominant seventh chords are altered extended chords (e.g., A7 (add9/#11) or D7 b9/#11). Funk also uses altered extended chords, but in this genre, songs are usually based on a vamp on a single chord, because rhythm and "groove are the key elements of the style. When extended chords are voiced in jazz or jazz fusion, the root and fifth are often omitted from the chord voicing, because the root is played by the bass player.

See also

- Added tone chord

- Elektra chord

- Hendrix chord

- Upper structure triad for an examination of extended harmony with emphasis on jazz and pop

References

- ↑ Cope, David (2000). New Directions in Music, p. 6. ISBN 1-57766-108-7.

- ↑ Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis, p.83. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

- 1 2 3 Benward & Saker (2009). Music in Theory and Practice: Volume II, p.184. Eighth Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- ↑ David A. Sheldon, ed., Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg (1989). Marpurg's Thoroughbass and Composition Handbook: A Narrative Translation and Critical Study, p.8, n.30. Pendragon Press. ISBN 9780918728555.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sadie, Stanley, ed. (1980). "Ninth chord", p. 252, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. 13. ISBN 1-56159-174-2.

- 1 2 3 Sadie, Stanley, ed. (1980). "Supposition", p. 373, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, vol. 18. ISBN 1-56159-174-2.

- ↑ Arnold, Ben, ed. (2002). The Liszt Companion, p.361. Greenwood. ISBN 9780313306891.

- ↑ Schweiger, Dominik and Urbanek, Nikolaus (2009). Webern_21, p.45. Böhlau Verlag Wien. ISBN 9783205771654.

- ↑ Shawn, Allen (2003). Arnold Schoenberg's Journey, p.120. Harvard. ISBN 9780674011014. "Technically a fifteenth chord".

Further reading

- Popp, Marius (1998). Applicatory Harmony in Jazz, Pop & Rock Improvisation. ISBN 973-569-228-7.

External links

- fretjam Guitar Theory – Extended Chords on Guitar

- Chord Construction - Learn Chord Construction