Military career of Napoleon Bonaparte

| Napoleon Bonaparte | |

|---|---|

Napoleon at the Bridge of the Arcole, by Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, (ca. 1801), Louvre, Paris | |

| Nickname(s) | General Vendémiaire, The Little Corporal, Napoleon the Great |

| Born |

August 15, 1769 Ajaccio, Corsica |

| Died |

5 May 1821 (aged 51) Longwood, St. Helena |

| Allegiance | France |

| Service/branch | Trained as an artillerist |

| Years of service | 1779 - 1815 |

| Rank | General, Emperor |

| Commands held |

Army of Italy Army of the Orient French Army Grande Armée |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Grand Master of the Legion of Honour Grand Master of the Order of the Reunion Grand Master of the Order of the Iron Crown Grand Master of the Order of the Three Golden Fleeces |

| Relations | House of Bonaparte |

| Other work | Sovereign of Elba, Writer |

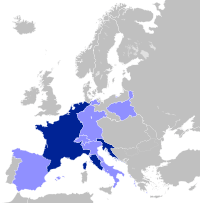

The military career of Napoleon Bonaparte lasted over 20 years. As emperor, he led the French Armies in the Napoleonic Wars. He is widely regarded as a military genius and one of the finest commanders in world history. He fought 60 battles, losing only seven, mostly at the end.[1] The great French dominion collapsed rapidly after the disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812. Napoleon was defeated in 1814; he returned and was finally defeated in 1815 at Waterloo. He spent his remaining days in British custody on the remote island of St. Helena.[2]

Napoleon Bonaparte (French: Napoléon Bonaparte, Italian: Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821) was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution. As Napoleon I he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1814, and briefly in 1815. The term "Napoleonic Era" is used by historians to broadly describe the period of his influence on politics, society, and warfare; although there is no consensus as to when the era began, it ended with his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, although his leadership and policies continued to effect Europe, even long after his death. From 1799, a complex series of events brought about Napoleon's opportunistic rise to power, ascension to Emperor leading to the founding of a French Empire, endless military campaigns throughout Europe, and ultimately his fall from grace in 1815. His military career, in excess of two decades of European conflict, is both extensive and formidable.

Rising through the ranks after studying at the French military academy, he would become an artillery officer. At the outset of the French Revolution, Napoleon would witness the effects of Parisian mob violence against trained troops, and became an exemplary officer in defence of revolutionary ideals. His firm beliefs would lead him to fight his own people, initially at the siege of Toulon, where he would play a major role in crushing the rebellion by expelling an English fleet, and securing the valuable French harbour. Almost two years later, he would face an uprising in the heart of Paris, utilising his skills as a gunner once again, to make the city safe. Promoted to général in 1795, Napoleon was sent to fight the Austro-Piedmontese armies in Northern Italy the following year. In just a year the campaign ended; in defeating both armies he became France's most distinguished field commander.

His life has remained a source of great study for historians, philosophers, military forces, scholars and academics worldwide.

Early years

Childhood

Napoleon was born in Ajaccio, on the French-occupied island of Corsica, in 1769, to parents who were of Genoese nobility by birth, though without riches and privileges,[3] allowing them, by way of a French scheme, to send their male children to be educated in a military school or to train for the priesthood, but at no cost.[4] Napoleon's military career began at an early age when, at the age of nine, he was enrolled in the military academy of Brienne-le-Château, France.[5] In 1784, at the age of fifteen, he progressed to the École Militaire in Paris. Since the age of twelve he had wanted to join the navy; the École Militaire was the next level of education whether he chose to follow a career in the army or navy.[6] As a cadet Napoleon graduated in just one year, rather than the normal two years, excelling in mathematics, and passing his exams. He received his first commission on 1 September 1785, at the age of sixteen, to sous-lieutenant in the Royal Artillery.[7]

Napoleon's father had died in February 1785,[8] and he wanted to be as close to his family as possible. Following his commission Napoleon joined the La Fère-Artillerie regiment, garrisoned in Valence, southern France, which placed him as close to his home island of Corsica as possible.[9] It was not until January 1786 that Napoleon took to his duties – until then he served a short time in the ranks – before pursuing his role as an artillery officer, where he continued to learn about ballistics and the latest in French fire power.[10] He took leave from September 1786, lasting nearly two years, returning home to his mother.[11] In June 1788 he returned to his regiment, which had moved to Auxonne, but during his first years in the military Napoleon spent most of his free time alone, studying – he enjoyed reading and writing about history and politics, whilst developing his own ideas about social reform throughout Europe.[12]

Start of the Revolution

From 1786, tensions started to rise as the economic situation in France led to national debt; bankruptcy was declared in August 1788[13] – a result of its expenditures, including continued investment in unutilised war preparations against Britain, and strong support during the American Revolutionary War (1775–83) which had cost between 1,066 million[14] and 2,000 million[15] livres, with little gain. The situation led to unfair taxation as it attempted to reduce the deficit. Despite the attempts of King Louis XVI, and several appointed Finance Ministers, to introduce land taxation for nobility, parlements refused to register them, but maintained taxes on the poorest French citizens.[16] Instead of solving the crisis it led to civil unrest and rioting – isolated at first – Napoleon was to witness mob rioting at Seurre, in March 1789,[17] but national distemperment was quickly spreading. Food prices and unemployment were high;[18] France was facing a crisis, whilst higher social-classes continued to avoid instigating reform. A National Assembly was formed to oppose Louis XVI, effectively transferring power and putting the middle-class – bourgeoisie and commoners – in charge of France from 17 June 1789. On 20 June, an oath, pledging "never to separate until an acceptable constitution was established", sanctioned its intentions.[19] It became the National Constituent Assembly on 9 July. Rioting culminated in the storming of the Bastille, Paris, on 14 July,[20] and nationwide panic followed, known as la Grande Peur (the Great Fear), as unrest spread rapidly across France.[21][22] On 26 August, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was adopted by the Assembly – foundations of a French constitution detailing articles of civil rights, which Napoleon had long held were necessary to limit the powers of the monarchy.[23] The nobility of France was soon to lose its privileges as the Assembly took control, becoming the ruling government, and forming the National Guard, militia – citizen soldiers – whose beliefs lay in a government serving "the people". Its power was bolstered by journées[a] such as the March on Versailles, on 5 October 1798, as thousands of angry women attacked the palace in Versailles, embittered over the lack and price of bread, and aiming to bring Louis XVI to Paris to rule amongst the people.[24] As Louis XVI surrendered his doubts and authority to the Assembly, France became a constitutional monarchy. The long-standing ancien régime, a socio-political system which defined divisions between the Estates of the realm, namely the clergy, aristocracy and commoners, had come to an end. The opening months of the revolution had been a realisation of Napoleon's ideals.[23] As an officer in a Royal Artillery regiment it was time for him to choose his side – King or country? With the threat of a counter-revolution, that could see sovereignty returned to the king, Napoleon was determined to defend the new constitution.[25]

Revolutionary idealist

1791–92

In 1768–69 the Corsican Republic had fallen to a French invasion.[26] During his free time Napoleon studied the history of Europe and Corsica; he had disliked the French administration and absolutism – Corsica once had its own independence until the French arrived. So when France decreed a constitution, Napoleon sought to end Corsican oppression. He returned to Corsica in October 1791, following the adoption of the French Constitution of 1791, on 3 September.[27] A Corsican National Guard was formed with Napoleon's encouragement, and following an election, in which Napoleon was a candidate, he became a lieutenant colonel in the Ajaccio Volunteers second battalion on 1 April 1792, at the age of twenty-two.[28]

After returning to Paris to account for his role in suppressing an Easter Sunday religious uprising in Ajaccio, he bore witnessing to violent rioting between the National Guard – encouraged by the Paris Commune – and Louis XVI's Swiss Guard, on 10 August 1792, at Tuileries Palace, resulting in the massacre of around 500 Swiss Guardsmen and 300 citizens.[29][30] Enmity was rising in Paris, and across the nation as Holy Roman Empire and Prussia, who opposed the revolution, invaded France intent on restoring the monarchy, an arrangement made formal by the Declaration of Pillnitz, in August 1791.[31] France was still bankrupt and its army had grown thin since the revolution began, whilst the population suspected Louis XVI of collaborating with royal families in Europe, seeking to reclaim control.[32] On 20 April 1792, France declared war on both countries. As a result of defending his actions in Ajaccio, and in embracing the revolution fervently, Napoleon was made a capitaine in the regular French army artillery once again, effective from 31 August 1792, whilst retaining his lieutenant colonelcy with the Corsican National Guard.[33]

Throughout September 1792, Paris was struck with further violence as mobs of Parisians of the Third Estate – more commonly known as sans-culottes (radical lower-class militant revolutionists) – took to the streets brutally murdering many priests of the First Estate, and aristocrats of the Second Estate as they sat in Paris' prisons.[34] The September Massacres occurred as a political group, known as the Jacobins, led by Maximilien Robespierre,[35] began to assume power. The National Assembly had become the Legislative Assembly on 1 October 1791, and was represented by two political groups whose opinions were split between those who considered the revolution a success and supported a constitutional monarchy, and those who distrusted the King and felt further measures were needed before France could re-establish itself.[36] The King's attempt to flee from France on 21 June 1791, with his wife, Marie Antoinette, in search of support from foreign allies, had destroyed all remaining public confidence in him. The "Flight to Varennes" resulted in their arrest, immediate return to Paris, and confinement in Tuileries.[37] The Assembly suspended Louis XVI's powers, and on 13 August, three days after the attack on the palace, the Royal family were arrested and placed in the Tour du Temple. On 20 September 1792, a new National Convention was formed to replace the Assembly; the monarchy was abolished the next day, and on 22 September the Convention declared the beginning of the French Republic.[38]

Napoleon left Paris amidst the September Massacres, returning to Ajaccio to resume his duty with the Corsican National Guard. The French army defeated an Austro-Prussian force at Valmy on 20 September 1792, and was on the offence against its erstwhile invaders.[39]

1793

Corsica

On 21 January 1793, in the heart of Paris, Louis XVI was publicly executed by guillotine.[40] The event caused uproar throughout Europe, whilst France remained defiant, with Marie Antoinette and her son Louis-Charles – despondent heir to the throne – still in prison, France's foreign enemies continued to grow. As the level of civil unrest remained high, the Convention faced the threat of civil war.[41] Napoleon had help deliver the French Constitution and its benefits to Corsica, his duty now required him to defend the constitution and Republic against surmounting opposition including,[39] from 1 February 1793, declaration of war on the Dutch Republic and Great Britain.[42]

South of Corsica, the island of Sardinia whose king had allied with the Austrians against France, became Napoleon's first military concern. Under the orders of the Convention, Corsica was to invade the Sardinian capital and force its capitulation. Corsican leader, Pasquale Paoli, had patriotically led his people, including Napoleon's father, against the 1768/69 French invasion, lost, and consequently had been exiled to Britain.[43] He returned, reinstated by the French government, in 1790, but became a royalist sympathiser and passive opponent of the course of the revolution.[44] Opposed to the invasion of Sardinia, Paoli sent Napoleon's battalion to invade the small island of La Maddalena, under the command of his nephew, Colonel Colonna-Cesari (French).[45] The expedition was supported by troops from Marseille, who were undisciplined and troublesome. The force left Corsica by sea on 18 February 1793, arriving on the 22 August. Napoleon played his part, as an artilleryman, intent on supporting a landing against a Sardinian fort by laying down heavy gunfire. But Colonna-Cesari refused to order an attack until 25 August, by which time the Marseille troops had determined not to engage the Sardinians and mutinied, forcing Napoleon, along with his senior commander and men, to return to the vessel, abandoning both their cannons and the mission.[46]

Napoleon didn't hesitate in openly casting aspersions against Colonna-Cesari and Paoli to the French Convention, who attempted to investigate the matter. Paoli resisted, once again opposing French rule over Corsican affairs. Napoleon's brother, Lucien, a strong supporter of the revolution and speaker at the Jacobin Club, denounced Paoli as a counter-revolutionist.[47] The Convention issued an arrest for Paoli, who in turn raised a revolt – Paoli's Corsican supporters sought to attack French officials, whilst all members of the Bonaparte family were declared outlaws, their livelihood destroyed – fleeing for their lives, they were forced to abandon Corsica on 10 June 1793 and resettle in France.[48]

Rebellion

Following the execution of Louis XVI and France's declaration of war on the Dutch Republic and Great Britain the Convention decreed a levy of 300,000 men through volunteers or conscription, to expand the French Revolutionary Army.[49] In March 1793, France also declared war on Spain. French opposition included Russia, Sardinia, Portugal, Naples and various Minor German states over the following months, mostly the result of British encouragement, resulting in the First Coalition.[50] Russia would, however, refuse to commit troops to the war and did not become an active participant in the coalition.[51]

In 1790, the Assembly had replaced the provinces of the ancien régime with a new set of boundaries, creating départments by which to administer the country, eliminate feudal land ownership, and create a more central government in Paris.[52] As an executive power the Convention sought to deal with France's economic problems through drastic means. Over the coming months it established a Revolutionary Tribunal in order to prosecute counter-revolutionists, decreed levée en masse (mass conscription), and passed the loi du maximum (Law of the Maximum) to fix and limit food prices due to frequent food riots in Paris. The law aimed to prevent hoarding by imposing capital punishment on those found guilty of price gouging or black marketeering.[53] In order to maintain order the Convention established "Revolutionary Armies" – authorised bands of patriots, typically sans-culottes, who would seek out offenders and deal with them.[54] The Convention also sought to deal with armed rebels and émigrés – aristocrats who had left France at the start of the revolution, some having returned – prescribing death to those who were caught.[55] It also established a number of revolutionary committees, in March 1793, including the Committee of Public Safety (CPS) whose aim was to protect the revolution from foreign influences and internal rebellion which, in July, received a new member – Robespierre.[56] From June that year, virtually all political opposition in the Convention had been expunged, resulting in a Jacobin-led government.

The response to the Convention's decrees was insurrection. As many as 70 of the 83 départments rejected a central government, although rebellion only became serious in eight of those.[57] The revolt in the Vendée began in March 1793 and would become a war in its own right.[58] Rebellious départments also included Lyon, Marseille and Toulon – France's three largest cities after Paris.[57][59] It was close to Marseille, where the Bonaparte family had resettled, that Napoleon would become involved in the civil war that was engulfing France.

Toulon

In July 1793, Napoleon was placed under the command of General Jean-Baptiste Carteaux to deal with rebels from Marseille situated in Avignon, where army munitions destined for the French Army of Italy were being stored. On 24 July, Carteaux's troops assaulted Avignon and successfully retook the town from rebellious guardsmen, but killed thirty citizens during the attack.[60] Napoleon went to nearby Tarascon to gather wagons for transporting the munition to the army. He visited Beaucaire, across the Rhône River from Tarascon, which had been holding its annual fair of Sainte-Madeleine. Napoleon arrived on 28 July, the last day of the fair, and visited a tavern where he ate and spoke with four merchants from Le Midi.[61] They discussed the revolution, subsequent rebellions, and their consequences. Napoleon concluded that by adopting the constitution of the Republic the civil war would end, and allow the regular army to restore France.[62]

Shortly after the meeting, possibly on the 29 July whilst still in Beaucaire, Napoleon wrote a political pamphlet titled Le souper de Beaucaire (The supper at Beaucaire) in which a soldier speaks with four merchants and sympathetic to their moderate opinions attempts to dissipate their counter-revolutionary sentiments.[63] After having it printed and distributed a copy reached Augustin Robespierre, brother of Maximilien Robespierre. He was impressed by its revolutionary tone although the pamphlet itself had no effect in deterring the rebels.[64] It served to advance Napoleon's career, however, recognised for his ambitions by Corsica-born friend and politician, Christophe Saliceti. Saliceti's influence in the Convention, along with fellow deputy Augustin Robespierre, advanced Napoleon into the position of Carteaux's senior gunner, on 16 September.[65][66]

On 24 August, Carteaux's troops reclaimed Marseille and executed around 500 people suspected of treason, all without trial.[61] Three days later, Toulon raised the Royalist flag. The following day, it admitted an Anglo-Spanish fleet into its harbour, whilst mostly British, but also Spanish and Piedmontese troops were permitted to garrison the city. The number gradually expanded to 17,000–18,000 troops, including Neapolitans and French émigrés, along with 28,000 citizens, many of whom supported the rebel cause.[67][68] As both a major naval arsenal and France's gateway to the Mediterranean Sea the loss of Toulon was unacceptable, but could prove difficult to recover.[69]

Napoleon's role as senior gunner initially proved difficult due to Carteaux's poor preparation for any siege. A lack of cannons, gunners and respect for the aspects and role of the artillery was immediately apparent. Starting from the day he arrived, on 18 September, Napoleon reorganised the artillery. He gathered additional guns from the region, whilst creating forges and workshops to manufacture shells and repair muskets, and training volunteers to fire them.[70] An arrangement of batteries were built around Toulon, opposing the British fleet and a number of enemy forts.[71] Saliceti once again recognised Napoleon's zeal, in addition to the need for experienced commanders, and recommended him for promotion. He was commissioned to chef de bataillon (major), on 18 October,[72] and his artillery was given independence from the army.[67] A week earlier Lyon had fallen, providing the Republic army surrounding Toulon with extra troops.[73] In order to have his proposals taken seriously, Napoleon wrote to the CPS, requesting a senior officer to command the artillery at Toulon. An aged General Jean du Teil was sent from the Army of Italy, but due to ill-health he left Napoleon to his own devices.[74] Carteaux was relieved, and on 16 November General Jacques Dugommier, a veteran of the Seven Years' War, took command of the siege.[75] The same day, in Paris, Marie Antoinette was executed.[76]

Napoleon was quick to determine, when he considered Toulon with its fortified harbour and high city walls, that any direct land attack would prove difficult and costly.[77] The inner harbour itself, a large basin with a narrow opening, was surrounded by high ground facing down onto Toulon but too distant for the available artillery to reach from Napoleon's position, on the western shore of the inner harbour. Anglo-Spanish troops occupied numerous forts around the city, including Fort l'Aiguillette whose position allowed for any occupant to command Toulon, the entire inner and outer harbour, and any fleet anchored therein.[67] Attempts were made to capture the height called Mount Caire which dominated Fort l'Aiguillette, on 22 September, but Carteaux provided insufficient troops to the effort, resulting in its failure.[78] Between Napoleon's artillery position and Fort l'Aiguillette, atop Mount Caire, a formidable earthwork called Fort Mulgrave was quickly built by the British and housed 24 cannon. The French nickname for it was Little Gibraltar.[79] Napoleon and Dugommier agreed that the capture of Mulgrave would cause Fort l'Aiguillette to fall, and that the British fleet would be unable to remain secure in the harbour, nor its troops in Toulon.[77] As Napoleon amassed artillery he put it to immediate use, firing hot rounds, to force the British fleet to move out of range, and closer to Toulon. Napoleon had one considerably long range gun, a 44-pound culverin, with which to reach across the 3 mile-wide (5 km) inner harbour.[80] This meant that Napoleon could not sink the fleet, but the distance also prevented the British from using their naval guns against any massed infantry attack on the forts.

On 15 December, after weeks of careful preparation, Napoleon's batteries began a bombardment of Fort Mulgrave, which lasted for two days. On 17 December, in bitter rain, General Dugommier led 7,000 infantry against Fort Mulgrave, in a night attack, with Napoleon leading the reserve. After several hours of fighting the fort was taken. L'Aiguillette and its neighbour, Fort Balaguier, were abandoned throughout the remainder of the day.[81] The next day, as predicted, the Anglo-Spanish began to withdraw under a constant barrage from the French Republic guns designed to maintain panic. They set fire to the naval arsenal warehouses and created fireships out of those French ships it could not take, which exploded violently.[82] On 19 December, the Republic troops entered Toulon. In recognition of his success Napoleon was provisionally commissioned to général de brigade (brigadier general) on 22 December, confirmed 16 February 1794; he was twenty-four years old.[83]

Military leadership

1794–96

Following the siege of Toulon, Napoleon spent time inspecting coastal defences before being posted to the Army of Italy as senior gunner, under General Pierre Dumerbion, which was engaged against the Piedmontese army in Northern Italy.[84] During the time he remained in the south of France, the Reign of Terror ran its course – Maximilien Robespierre had become head of the CPS acting with the capacity of a dictator.[85][86] The CPS itself became the de facto government as Robespierre sought to purge France of anyone suspected of counter-revolutionary behaviour regardless of class. Extreme measures and unpopular laws passed by the CPS, and "the incorruptible" sentiments of Robespierre and his closest followers, would ultimately lead to its downfall. On 27 July 1794, the coup of 9 Thermidor An II (date of the French Republican Calendar[b] (FRC)) saw members of the government, highly opposed to the CPS's overwhelming power, displace Robespierre and his followers. On the 28 July, Robespierre and many of his associates were executed including his brother, Augustin, and several members of the Revolutionary Tribunal, which had sent around 2,500 citizens of Paris to their deaths over the past ten months.[87][88]

Napoleon had not only received Augustin's favour through writing Le souper de Beaucaire, but as an officer in the Army of Italy of which Augustin was a représentant en mission, resulting in their friendship.[84] Saliceti had also been a representative of the Convention, and, possibly looking to distance himself from persecution, began to identify those who may have collaborated with the former radical, Robespierre.[89] Napoleon was arrested in Nice, on 6 August 1794, his behaviour and movements thoroughly investigated, and was released in less than two weeks without charge. Napoleon resumed his role with the Army of Italy,[90] and saw his first pitched battle at Dego in September.[91] He returned to Toulon in November to help plan an invasion of Corsica, but the attempt was prevented by the British navy in March 1795, and on 7 May Napoleon found himself assigned to command the artillery of the Army of the West, which was still engaged in the Vendée revolts.[92] Napoleon went to Paris to seek reassignment to Italy, but found himself rejected by the dogmatic Minister of War and unoccupied for several months as the government continued to shuffle personnel around and dismiss – or execute – unwanted pro-Jacobin generals following 9 Thermidor.[93] His skills as a competent strategist were recognised by the newly appointed war minister, Doulcet de Pontécoulant, but instead of being posted to the army he was placed in the Bureau Topographique, from 20 August – planning centre of the CPS which drew up campaigns for its armies.[94][95]

On 22 August, the Constitution of the Year III was passed. The constitution decreed to replace the Convention with a bicameral government – an upper house, the Council of Ancients, and a lower house, the Council of Five Hundred – and the Directory compromising of five Directors with executive power.[96] The constitution, however, included a highly unpopular law which decreed that two-thirds of the new legislature would come directly from the current Convention. This posed the threat of Jacobin policies being prolonged and caused massive public distrust in Paris.[97] Royalists, encouraged by émigrés,[98] began to rise up in revolt against the Convention, demanding free elections and, in some cases, restoration of Louis XVIII (in exile) as King.[99] On the night of 4–5 October, 13 Vendémiaire An IV (FRC), mobs of thousands marched through Paris headed for the Tuileries where the Convention sat. Paris was divided into 48 sections, 32 of which had taken to the streets en masse,[100] resulting in as many as 25,000 rebels moving against 5,000 regular troops, and around 3,000 sans-culottes loyal to the constitution.[101] Whilst there were many isolated fights throughout the center of Paris, Commander-in-Chief Paul Barras was in command of the Convention's defence. He knew Napoleon, having also been at Toulon,[102] and so offered him command of the artillery, which needed to be retrieved from a camp, 6 miles (10 km) away, by cavalry. Upon arrival, 40 cannon were strategically situated around the gardens and streets leading to the palace, and were loaded with grapeshot. When the rebel force arrived they were fired upon with muskets, initially, but after refusing to fall back the guns opened fire, inflicting casualties, and eventually forcing the crowd to disperse as they failed to press their advantage in numbers, despite several hours of fighting. Although only around 300–400 people were killed, the Royalist cause was defeated.[103]

On 10 October, Barras made Napoleon his second-in-command of the Army of the Interior. He was further promoted to général de division (divisional general) on 16 October. As a result of Barras becoming a Director, and having to select an able successor, was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Army of the Interior, from 26 October.[104] At the age of 26, Napoleon had suddenly advanced from being a little known artillery officer to becoming commander of France's largest army.[105] It was, however, to be a short appointment. The Army of the Interior was a force that maintained law and order, engaged rebels, and enforced the draft for the levée en masse. Napoleon remained in Paris for about 6 months, replacing its former rebellious National Guard with a centralised Parisian Guard, and purging the city of any Royalist and Jacobin remnants that might threaten the government further.[106] During this time, he was aware of the lack of action being taken by the Army of Italy, and repeatedly made his concerns known to the Directory regarding the lack of action being made against the Piedmontese and Austrian armies in the winter of 1796, expressing his beliefs that any wasted opportunity would result in the campaign being lost.[107] Following the resignation of General Barthélemy Schérer, in March 1796, Napoleon was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Army of Italy.[108] On the 9 March he married Joséphine de Beauharnais, before leaving Paris on the 11 March.[109] He arrived in Nice on 27 March, and took official command of the Army of Italy.[110]

1796–97: Italian Campaigns

Napoleon's campaign against Austro-Piedmontese forces in Northern Italy began with the Montenotte Campaign on 10 April 1796. The Austrian army, commanded by Feldzeugmeister (General) Johann Beaulieu, and Sardinia-Piedmont army by Feldmarschall-Leutnant (Lieutenant-General) Michelangelo Colli,[111] engaged French forces in a rapid series of battles. They were driven apart as Napoleon advanced his army between them, preventing them from consolidating against him. Engagements continued for almost two weeks in the Ligurian Alps until, following the Battle of Mondovi on 19–21 April, Colli was forced to capitulate. On 28 April, the Armistice of Cherasco was signed, the Kingdom of Sardinia withdrew from the First Coalition, leaving Austria to face Napoleon alone.[112] On 10 May, he defeated the Austrian rearguard at the Battle of Lodi, in the Po Valley, and by 15 May the French occupied Milan,[113] a major city in Northern Italy, and capital of the Lombardy region, an Austrian province. In the space of a few short weeks, Napoleon had proven himself a competent battlefield general, and had gained the respect of his troops, who nicknamed him "le petit caporal" ("the little corporal") after seeing him take personal command of the artillery at Lodi.[114]

The Austrian army withdrew to the east following its defeat at Lodi. Beaulieu situated his forces across the River Mincio, using its adjoining lakes to protect his flanks, but in an attempt to protect all possible river crossings he spread his army too thin and without a reserve.[115] Napoleon pressed the center of his line at the Battle of Borghetto, on 30 May, forcing an Austrian retreat. 4,500 troops separated from the main force retired to the fortress at Mantua where, on 4 July, the French would begin an eight-month siege of Mantua.[116]

The fortress of Mantua was but one of four located in Northern Italy positioned close to the Alpine passes leading to Austria.[117] Known as the Quadrilatero (meaning Quadrilateral), these fortresses were of strategic importance to Austria for maintaining military authority over Lombardy and the Republic of Venice.[118] The French had taken the fortresses at Peschiera, Legnago and Verona following the victory at Borghetto, but Mantua was surrounded by swamps and three lakes, protected by 316 guns, and held a garrison of 12,000 troops, making any siege difficult.[119] In late June, Feldmarschall (Field Marshall) Dagobert Würmser replaced Beaulieu and led the Austrian army on an offensive campaign to relieve Mantua.[120] Mindful of its approach from the north, Napoleon was forced to lift the siege on 31 July in order to confront Würmser's 50,000 strong army with his full force, sacrificing 179 guns in the process.[120]

Würmser split his army into three columns, intent on converging on the French at Mantua.[121] Verona was retaken on 29 July, whilst the right column severed French communications back to Milan.[121] Napoleon moved fast, aiming to defeat the divided Austrian army in detail, as he had done during the Montenotte Campaign. He fell upon the right wing, a division under Feldmarschall-Leutnant Peter Quosdanovich, on 3 August at the Battle of Lonato.[122] Fighting continued on 4 August when Würmser's 4,000 strong vanguard attempted to support Quosdanovich from the south but was impeded, allowing Napoleon to defeat Quosdanovich's division, which was forced to retreat due to heavy losses.[122]

Würmser had resupplied Mantua in absence of any siege, and situated his army at Castiglione, south of Lonato. On 5 August Napoleon quickly turned his attention to the main Austrian force. The Battle of Castiglione was a pitched battle which led to Würmser's 25,000 strong force retreating, having suffered 2,000 casualties. It retired eastwards, then back towards the north, but Napoleon's troops were too tired to pursue.[123] The French regained Verona on 7 August before returning to Mantua,[124] which was now occupied by 17,000 troops. Having abandoned the siege train to engage Würmser, Napoleon was compelled to blockade Mantua and await its surrender once food and supplies were depleted. His own troops were badly equipped, improperly dressed, and mostly barefoot.[125] Their morale was low, and had been since the start of the campaign,[126] yet it had somehow managed to defeat the Piedmontese and Austrians at every major engagement. The inspiration he gave his troops led the Directory to become suspicious about his ambitions, and had his motives investigated. The resulting report was highly in Napoleon's favour, and their support for his independent command increased henceforth.[127]

In mid-August 1796, with French armies advancing along the Rhine into Germany, the Directory ordered Napoleon to take the Army of Italy northwards to prevent Austrian forces from consolidating against the offensive.[128] 10,000 troops remained at Mantua to uphold the blockade and protect the 33,000 strong French rear as it headed for Trento, headquarters of Würmser's army.[128] Würmser left Trento in early September with 20,000 troops, heading south-east via the Brenta valley, seeking to approach and relieve Mantua from the north-east. Napoleon has been unaware of his departure, and on 4 September defeated Feldmarschall-Leutnant Paul Davidovich at the Battle of Rovereto, forcing him to evacuate Trento and retreat northwards.[129] Taking the initiative, on 6 September Napoleon opted to pursue Würmser down the Brenta valley, leaving 10,000 infantry at Trento to guard his route. Moving to a rapid pace, the French caught up with the Austrian force on 8 September and engaged them in the Battle of Bassano. Although his force was divided in defeat, Würmser continued hurriedly towards Mantua. Arriving on 12 September, 16,000 Austrians forced their way through the French lines, raising the city garrison to 23,000. With Würmser sealed in, his baggage and guns abandoned at Bassano, he no longer posed a threat.[130]

As the siege continued, Napoleon established three new client republics in Northern Italy, namely Cisalpine Republic, Cispadane Republic and Transpadane Republic.[131] By November 1796, a new Austrian commander, General József d'Alvinczi, an Austrian baron, whose military experience could threaten Napoleon's plans.[131] Alvinczi divided his 46,000 strong force into two corps, sending 18,000 to retake Trento, under Davidovich, as a diversion, whilst he advanced from the east with 28,000 men, his objective being Verona, the French central position.[132] 10,000 French under Général de division Claude Vaubois were to face off the army to the north, as Napoleon moved to confront d'Alvinczi's main army. Trento fell to the Austrians on the 4 November and Napoleon's troops were forced to withdraw at the Second Battle of Bassano on 6 November.[133] Davidovich defeated Vaubois' division at the Battle of Calliano, the next day, inflicting severe casualties.[133] However, Davidovich failed to press his advantage and continue to support d'Alvinczi, and remained idle. Quick to take advantage of this inactivity, Napoleon advanced, engaging d'Alvinczi at the Battle of Caldiero on 11 November. Having sustained heavy losses, Napoleon was compelled to fall back to Verona.[134] Finding himself in a desperate situation, with Davidovich's army to the north barely contained by Vaubois, d'Alvinczi's force to the east, and the possibility of Würmser's troops being released from Mantua, Napoleon openly began to doubt that the Italian campaign could succeed.[134]

Arcole Campaign

Napoleon formulated a new strategy, planning to move rapidly around d'Alvinczi's army, to take Villanova, at his rear, 16 miles (25 km) east of Verona. By doing this, he hoped to capture the Austrian supply trains and weaken their lines of communication, which would force them to retreat and engage him in marshland, on a small front which would deny them any advantage their superior numbers held.[135] Knowing this would leave Verona vulnerable, and may allow Davidovich to push south and join with d'Alvinczi, he left a small garrison of 3,000 to defend the city and departed during the night of 14 November, with 18,000 men, using the River Adige to cover his movements.[136]

On 15 November, the French crossed to the north side of the river, using a pontoon bridge built by sappers, at Ronco. In order to reach Villanova, the tributary river Alpone had to be crossed at the village of Arcole, but d'Alvinczi was aware of Napoleon's plans and had reinforced the bridge there with 4,000 Croatian troops and several guns.[136]

For three days, the French pressed the defenders of Arcole. Having sustained heavy losses, Napoleon encouraged his tired men to follow him across the bridge, a tricolour held aloft in his hands. French troops crossed the river south of Arcole, on 17 November, and with diversionary cavalry support, encouraged the Austrians to withdraw. D'Alvinczi retired from Verona, leaving his forces divided east and west of the Alpone. Now holding the advantage, Napoleon attacked the weaker Austrian wing in the marshes, and continued to press north against the main force as it retreated east to Vicenza, French cavalry in pursuit.[137]

On 17 November, Davidovich routed Vaubois' division at Rivoli. Having secured Verona, Bonaparte marched to Vaubois' aid with his main force, and defeated the remaining Austrian threat at Rivoli on 21 November. Davidovich, outnumbered and no longer capable of supporting d'Alvinczi, abandoned his bid to reach Mantua. With the third Austrian relief attempt a failure, the siege continued. Against overwhelming odds, Napoleon had succeeded in maintaining his position for a while longer, and his military genius was beginning to show.[138]

By the end of 1796, d'Alvinczi had reinforced his numbers to 45,000. The Army of Italy's strength was increased to around 45,000 also, although 10–12,000 were required to maintain the siege. French units were garrisoned north and east of Mantua, along the Adige, covering all possible approaches that the Austrians might take in a further relief attempt, which was expected after peace negotiations between the French Directory and the Emperor of Austria hit an impasse.[139]

1797: Rivoli

In early January, 1797, d'Alvinczi sent units to attack Verona, Legnago, and points along the Adige. Napoleon, however, was certain that the enemy numbers did not constitute a serious threat, and did not commit himself to a stronger defence. On 13 January, Napoleon received word from Général de brigade Barthélemy Joubert, Vaubois' replacement,[140] that a large Austrian force had attacked his division at La Corona, 5 miles (8 km) north of Rivoli, the day before. With around 6,000 Austrians moving against Verona and 9,000 against Legnago, Napoleon determined that d'Alvinczi had taken his main force, 28,000 troops, north-west through the Brenta valley to Trento, and was pushing south for Mantua.[141]

Napoleon proceeded to join Joubert, where the engagement had already begun on the plateau north of Rivoli, on 14 January. The battle continued into the next day, with French reinforcements arriving to repel the Austrian assault.[142]

Napoleon left command of the battle to Joubert, as he rushed south, where 9,000 Austrians under Feldmarschall-Leutnant Giovanni Provera had succeeded in crossing the Adige and were within sight of Mantua. Despite their efforts to break through French lines, Napoleon's arrival with a division to their rear blocked any chance of advance or retreat, leading to the surrender of 6,000 troops.[143] The Battle of Rivoli also ended that day. From 28,000 Austrians, about 4,000 casualties and 11,000 prisoners resulted. The remaining fled north, utterly defeated.[144] The French lost around 5,000 men.[145] Of d'Alvinczi's original strength, only 13,000 fragmented troops remained.[146]

Würmser made a futile attempt to link up with Proversa on 16 January. On 2 February, with almost half of his 30,000 strong garrison sick with disease and hunger, Würmser surrendered.[146] Despite his long-awaited victory, Napoleon immediately moved south, invading Italy's Papal States and securing the Treaty of Tolentino on 19 February.[147]

In late February, Napoleon pressed east, aiming to take Vienna and end the war. In command of the army that was to prevent the French from gaining passage through the Eastern Alps into Austria was Archduke Charles of Austria – who, at 25 years old, was two years younger than Napoleon – the commander who had prevented the French Army of the Rhine from invading Germany in 1796.[148] By mid-March, Napoleon's advances made headway, pushing the Austrians back, but by April he suffered a loss of momentum as the Army of the Rhine failed to converge with the Army of Italy, leaving him with insufficient numbers to capture Vienna.[149] After calling for a ceasefire, Napoleon called for negotiations, without seeking the Directory's permission or waiting for an official diplomat. Situated in Leoben, 75 miles (120 km) short of the capital, he successfully bluffed the Austrians into thinking he was ready to attack in strength. On 17 April, the Preliminaries of Leoben were signed, forming a basis for the Treaty of Campo Formio, signed on 18 October 1797. As territorial rights were settled, Napoleon returned to Paris in December a household name.[150]

1798: Egyptian Campaign

At the end of 1797, Great Britain – all that remained of the First Coalition – was France's greatest threat. An assured peace between the French Directory and King George III, or Prime Minister William Pitt, seemed unlikely. Napoleon was directed to organise an invasion of England, with the Army of England, numbering 120,000 men, but upon inspection he determined that without control of the English Channel such an invasion would be costly or impossible.[151] He offered the Directory several alternative uses for the army, the most pertinent describing an invasion of Egypt, in order to disrupt major English trade routes into Europe from Africa, Asia, and its wealthy colonies in the Indies, supplying commodities such as coffee, sugar, rice and cotton.[152] Tipu Sultan, ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India, could prove a valuable French ally during the invasion – having fought against the British in all three Anglo–Mysore Wars, since 1766 – he was a formidable supporter of the revolution itself.[153]

Napoleon's invasion plan was approved in March 1798, and preparations for the expedition were soon underway.[154] An Army of the Orient, totalling 40,000 men, guns and supplies, was assembled in readiness to embark from various southern harbours and Corsica.[155][156] Secrecy regarding the destination was maintained by the Directory and Napoleon's senior staff, so that foreign spies aware of the assembling force could not identify its target with any certainty.[157] A Royal Navy squadron was sent to investigate, commanded by Rear Admiral Horatio Nelson. Any discovery posed a threat to the campaign, and the British navy could not be allowed to consolidate its strength in the Mediterranean to oppose the French fleet.[155]

Napoleon arrived in Toulon on 9 May, where his 120-gun flagship, L'Orient, and 215 other various sized warships, corvettes, frigates, and transport vessels were ready for departure.[158] A mistral wind blew up on the 12 May, halting his plans to set sail that day. The storm persisted for a week before settling on 19 May, allowing the vast fleet to set course.[159] On 21 May, Nelson's squadron was hit by a gale storm, demasting Nelson's flagship and forcing him to seek harbour for repairs. As a result of the British vessels being divided and ineffectual, the French fleet entered the Mediterranean without incident.[160]

Malta

On 9 June, the French fleet arrived at the island of Malta, and invaded its capital, Valletta, which was defended by around 330 Knights of St John, around 200 of whom were French and unwilling to fight. On 11 June, following brief negotiations, Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch surrendered, without ever a shot being fired.[161][162] The invasion of Malta had been planned long in advance, and during the week following its capitulation, the French seized Maltese riches in order to further finance the expedition. Napoleon applied modern law and reform, abolishing feudal rule and slavery – 2,000 Turks and Moors were freed – he extended education to cover the French Constitution, and granted equal rights to Christians, Jews and Muslims.[163] The old and unpopular Order was gone, the latest victim of the revolution. Around 2,000 Maltese troops, French Knights and freed slaves, joined Napoleon's army when it resumed course for Egypt on 19 June.[164]

Alexandria

The French fleet approached the Egyptian coastline on 30 June, successfully evading the British navy by feinting eastward towards Crete, their paths having crossed unaware during the misty night of 22–23 June.[165] Sailing south-east from Malta, Nelson's faster ships had overtaken the French and arrived at Egypt as early as 28 June, before heading north, still unaware of where Napoleon intended to land his force, Nelson continued to search.[166] Details of the actual landings were ill-prepared, and Napoleon selected a beachhead 5 miles (8 km) west of Alexandria, whose enclosed harbour he did not consider safe to enter. Fleet Vice-Admiral François-Paul Brueys refused to anchor any closer than 3 miles (5 km) to the shore due to uncharted shoals. On 1 July, the slow process of landing began.[167]

When Napoleon and his staff came ashore on 2 July, with less than 4,000 troops carrying rationed ammunition, and no chance of cavalry or artillery support, he recognised the urgency to secure Alexandria's harbour so he could unload supplies, and use its wells to provide water for his men who quickly became thirsty in the African heat.[168] Harassed by Bedouin cavalry, he advanced on Alexandria, facing a garrison of around 500 Egyptians and 20 Mamluks, whose Bey leader – situated in Cairo and communicating by messenger – was certain a French force on foot could be defeated.[169] The French attack was swift, and despite facing resistance from both soldiers and citizens the city fell by the afternoon, with less than 50 French dead compared to 700–800 Egyptian casualties.[170] Accounting for the high total, Adjudant-général (adjutant general) Pierre-François Boyer (French) wrote that French troops spent four hours slaughtering inhabitants who had taken refuge in mosques.[171]

Once secured, the fleet continued unloading remaining troops, horses and guns, in the city port.[172] By 3 July, the majority of Napoleon's forces were on-land, and having negotiated terms with the local Egyptians, Arabs and Ottoman Turks, by claiming to be in Egypt only to fight the Mamluk beys for harassing French merchants,[173] he quickly established order. Napoleon appealed to the Muslim faith, warned off aggression from the population, and promised to free Egypt of Mamluk rule, before sending the first elements of his army south-east, towards Cairo.[174]

Cairo

The march to Cairo would take several weeks, with French troops crossing the desert whilst a flotilla of chebecs was sent down the Nile carrying supplies and to serve as gunboats.[175][176] Napoleon joined his desert-bound army on 6 July, concentrating 18,000 men at Damanhur on 9 July before moving towards the Nile.[177] With insufficient rations and their uniforms proving inadequate for the harsh environment, the 72-hour desert-crossing resulted in severe thirst and dehydration. Bedouin tribesmen filled wells with sand and picked off French stragglers who became sick or lost during sand storms, often blinded; many became delirious and committed suicide.[178] Although Napoleon had made agreements with to prevent hostilities, a fatwa had been issued by Cairo's clerics, ordering all true Muslims to take up arms against the French "infidels".[179] All locals now posed a threat to the expedition.

On 13 July, whilst approaching Shubrâkhît, a village on the Nile, Napoleon's troops were attacked by 4,000 Mamluk cavalry and 12,000 fellahin (militia composed of peasants), led by Murad Bey.[177] On the Nile, his supply ships were ambushed by a number of gunships, supported by cannons positioned along the shore.[180] The battle at Shubrâkhît was brief, with Napoleon forming his divisions into infantry square formations six men deep, with cannons placed at the corners to resist cavalry charges. He also ordered artillery to support his gunboats against the enemy vessels. A direct hit against the Mamluk flagship's magazine resulted in a huge explosion.[181] Murad's army fled from the field, demoralised by the loss, having caused very few casualties on-land, but several hundred French sailors were killed as a result of boarding and vicious hand-to-hand combat with scimitars.[182]

By 18 July the French army arrived at Wardan where they were granted 48 hours of rest before pressing on to Cairo.[183] Making one final stop on 20 July, 18 miles (29 km) away from the capital, the sick and weary army of 25,000 men were once again marching south several hours before dawn, 21 July, as Napoleon anticipated the upcoming battle.[184]

The Battle of the Pyramids, which took place on the afternoon of 21 July, would more accurately be described as the "Battle of Embabeh", a village on the north-east banks of the Nile, 1 mile (1.6 km) from Cairo. It was here that joint-rulers of Egypt, Murad and Ibrahim Bey,[c] prepared to meet the French. Though contemporary art often displays the battle at the foot of the Pyramids of Giza themselves, the fighting took place 8–10 miles (13–16 km) north-east of the necropolis.[185] Napoleon pointed them out to his troops declaring, "You are going into a battle which will be engraved upon the memory of mankind. You will be fighting the oppressors of Egypt. Soldiers, forty centuries of history are looking down on you".[186] In reality, the distance and haze would have made the sight less impressive than Romanticist artists such as Antoine-Jean Gros or François Watteau depict in their works.

Forming each of his five divisions into large rectangular "squares" along a 2 mile (3 km) front, with the Nile protecting his left flank, Napoleon prepared to receive the Mamluk charge. Murad, leading 6,000 cavalry, attempted to break the French right flank and rear.[184] Two divisions of the French left stormed Embabeh, held by 12,000 fellahin, inciting panic. Ibrahim watched from across the Nile as the engagement developed, but had insufficient boats with which to cross and support Murad with his own army.[187] Lacking coordination, the Mamluk cavalry was unable to penetrate the deep French lines as they sustained casualties. In less than two hours, having lost several thousand men to less than 300 French casualties (of which only 29 dead), Murad and his troops were routed, many drowned after diving into the Nile as they fled. Ibrahim, having never joined the fight, ordered a general retreat east into Syria. On 22 July, Cairo surrendered and was occupied on 24 July.[188]

| “ | Soldiers, forty centuries of history are looking down on you. | ” |

Trapped in Egypt

Battle record

- Key to flags

- Key to campaigns

| 1 | War of the First Coalition | 2 | War of the Second Coalition |

| ※ | Montenotte Campaign | 6 | Six Days Campaign |

- Key to outcome

| ⁂ | Decisive victory | † | Decisive defeat |

| Date | War | Action | Opponent/s | Type | Country | Rank | Outcome | Record | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 Sep – 18 Dec 1793 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Siege of Toulon | Siege | France | Major | Victory

|

1–0 | [189] | |

| 21 Sep 1794 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | First Battle of Dego | Battle | Italy (Kingdom of Sardinia) | Brigadier General | Victory

|

2–0 | [190] | |

| 11–12 Apr 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Montenotte※ | Battle | Italy (Republic of Genoa) | General | Victory

|

3–0 | [191][192] | |

| 14–15 Apr 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Second Battle of Dego※ | Battle | Italy (Kingdom of Sardinia) | General | Victory

|

4–0 | [193] | |

| 16 Apr 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Ceva※ | Battle | Italy (Kingdom of Sardinia) | General | Victory

|

5–0 | [194] | |

| 19–21 Apr 1796[x1] | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Mondovì※ | Battle | Italy (Kingdom of Sardinia) | General | Victory

|

6–0 | [195][196][197] | |

| 7–9 May 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Fombio | Skirmish | Italy (Duchy of Milan) | General | Victory

|

7–0 | [198] | |

| 10 May 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Lodi | Battle | Italy (Duchy of Milan) | General | Victory

|

8–0 | [199][200] | |

| 30 May 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Borghetto | Battle | Italy (Venetian Republic) | General | Victory

|

9–0 | [201] | |

| 4 Jul 1796 – 2 Feb 1797 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Siege of Mantua | Siege | Italy (Duchy of Mantua) | General | Victory

|

10–0 | [202] | |

| 3–4 Aug 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Lonato | Battle | Italy (Venetian Republic) | General | Victory | 11–0 | [203] | |

| 5 Aug 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Castiglione | Battle | Italy (Duchy of Mantua) | General | Victory | 12–0 | [203][204] | |

| 4 Sep 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Rovereto | Battle | Italy (County of Tyrol) | General | Victory | 13–0 | [205] | |

| 8 Sep 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Bassano | Battle | Italy (Venetian Republic) | General | Victory | 14–0 | [206] | |

| 6 Nov 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Second Battle of Bassano | Battle | Italy (Venetian Republic) | General | Defeat | 14–1 | [133] | |

| 12 Nov 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Caldiero | Battle | Italy (Venetian Republic) | General | Indecisive | 14–1 | [207] | |

| 15–17 Nov 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of the Bridge of Arcole | Battle | Italy (Venetian Republic) | General | Victory | 15–1 | [207][208] | |

| 22 Nov 1796 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Calliano | Battle | Italy (Venetian Republic) | General | Victory | 16–1 | [209] | |

| 14–15 Jan 1797 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Rivoli | Battle | Italy (Venetian Republic) | General | Victory⁂ | 17–1 | [210][211] | |

| 16 Mar 1797 | French Revolutionary Wars1 | Battle of Valvasone | Battle | Italy (Venetian Republic) | General | Victory | 18–1 | [210][212] | |

| 2 Jul 1798 | Egypt–Syria Campaign | Siege of Alexandria | Siege | Egypt | General | Victory | 19–1 | [213][214] | |

| 13 Jul 1798 | Egypt–Syria Campaign | Battle of Shubra Khit | Battle | Egypt | General | Victory | 20–1 | [215] | |

| 21 Jul 1798 | Egypt–Syria Campaign | Battle of Pyramids | Battle | Egypt | General | Victory⁂ | 21–1 | [216][217] | |

| 11 Aug 1798 | Egypt–Syria Campaign | Battle of El Saliyeh | Skirmish | Egypt | General | Victory | 22–1 | [218][219] | |

| 8–19 Feb 1799 | Egypt–Syria Campaign | Siege of El Arish | Siege | Egypt | General | Victory | 23–1 | [220] | |

| 3–7 Mar 1799 | Egypt–Syria Campaign | Siege of Jaffa | Siege | Egypt | General | Victory | 24–1 | [221] | |

| 17 Mar – 21 May 1799 | Egypt–Syria Campaign | Siege of Acre | Siege | Israel | General | Defeat | 24–2 | [222] | |

| 16 Apr 1799 | Egypt–Syria Campaign | Battle of Mount Tabor | Skirmish | Israel | General | Victory | 25–2 | [223] | |

| 25 Jul 1799 | Egypt–Syria Campaign | Battle of Abukir | Battle | Egypt | General | Victory⁂ | 26–2 | [224] | |

| 14 Jun 1800 | French Revolutionary Wars2 | Battle of Marengo | Battle | Italy (Kingdom of Sardinia) | General | Victory⁂ | 27–2 | [225][226] | |

| 15–19 Oct 1805 | War of the Third Coalition | Battle of Ulm (Ulm Campaign) | Skirmish | Germany (Bavaria) | Emperor | Victory⁂ | 28–2 | [227][228] | |

| 2 Dec 1805 | War of the Third Coalition | Battle of Austerlitz | Battle | Austria | Emperor | Victory⁂ | 29–2 | [229][230] | |

| 14 Oct 1806 | War of the Fourth Coalition | Battle of Jena-Auerstedt | Battle | Prussia | Emperor | Victory⁂ | 30–2 | [231] | |

| 23–24 Dec 1806 | War of the Fourth Coalition | Battle of Czarnowo | Battle | Poland | Emperor | Victory | 31–2 | [232] | |

| 7–8 Feb 1807 | War of the Fourth Coalition | Battle of Eylau | Battle | Prussia | Emperor | Indecisive | 31–2 | [233][234] | |

| 14 Jun 1807 | War of the Fourth Coalition | Battle of Friedland | Battle | Prussia | Emperor | Victory⁂ | 32–2 | [235][236] | |

| 30 Nov 1808 | Peninsular War | Battle of Somosierra | Battle | Spain | Emperor | Victory | 33–2 | [237] | |

| 20 Apr 1809 | War of the Fifth Coalition | Battle of Abensberg | Battle | Germany (Bavaria) | Emperor | Victory | 34–2 | [238] | |

| 21 Apr 1809 | War of the Fifth Coalition | Battle of Landshut | Battle | Germany (Bavaria) | Emperor | Victory | 35–2 | [239] | |

| 21–22 Apr 1809 | War of the Fifth Coalition | Battle of Eckmühl | Battle | Germany (Bavaria) | Emperor | Victory | 36–2 | [240][241] | |

| 23 Apr 1809 | War of the Fifth Coalition | Battle of Regensburg | Battle | Germany (Bavaria) | Emperor | Victory | 37–2 | [242] | |

| 21–22 May 1809 | War of the Fifth Coalition | Battle of Aspern-Essling | Battle | Vienna | Emperor | Defeat | 37–3 | [243][244] | |

| 5–6 Jul 1809 | War of the Fifth Coalition | Battle of Wagram | Battle | Austria | Emperor | Victory⁂ | 38–3 | [245][246] | |

| 16–18 Aug 1812 | Invasion of Russia | Battle of Smolensk | Battle | Russia | Emperor | Indecisive | 38–3 | [247][248] | |

| 7 Sep 1812 | Invasion of Russia | Battle of Borodino | Battle | Russia | Emperor | Victory | 39–3 | [249][250] | |

| 24 Oct 1812 | Invasion of Russia | Battle of Malojaroslawetz | Battle | Russia | Emperor | Indecisive | 39–3 | [251] | |

| 14–18 Nov 1812 | Invasion of Russia | Battle of Krasnoi | Battle | Russia | Emperor | Defeat | 39–4 | [252] | |

| 26–29 Nov 1812 | Invasion of Russia | Battle of Berezina | Battle | Russia | Emperor | Victory | 40–4 | [253][254] | |

| 2 May 1813 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Lützen | Battle | Germany (Leipzig) | Emperor | Victory | 41–4 | [252][255] | |

| 20–21 May 1813 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Bautzen | Battle | Germany (Saxony) | Emperor | Victory | 42–4 | [256][257] | |

| 22 May 1813 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Reichenbach | Battle | Germany (Saxony) | Emperor | Indecisive | 42–4 | [258] | |

| 26–27 Aug 1813 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Dresden | Battle | Germany (Saxony) | Emperor | Victory | 43–4 | [259][260] | |

| 16–19 Oct 1813 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Leipzig | Battle | Germany (Saxony) | Emperor | Defeat† | 43–5 | [261][262] | |

| 22 Oct 1813 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Eckartsberga | Battle | Germany (Saxony) | Emperor | Victory | 44–5 | [263] | |

| 26 Oct 1813 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Hörselberg | Battle | Germany (Saxony) | Emperor | Indecisive | 44–5 | [263] | |

| 30–31 Oct 1813 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Hanau | Battle | Germany (Hesse) | Emperor | Victory | 45–5 | [264][265] | |

| 29 Jan 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Brienne | Battle | France | Emperor | Victory | 46–5 | [266][267] | |

| 1 Feb 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of La Rothiere | Battle | France | Emperor | Defeat | 46–6 | [268][269] | |

| 10 Feb 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Champaubert6 | Battle | France | Emperor | Victory | 47–6 | [270] | |

| 11 Feb 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Montmirail6 | Battle | France | Emperor | Victory | 48–6 | [271][272] | |

| 12 Feb 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Château-Thierry6 | Battle | France | Emperor | Victory | 49–6 | [273] | |

| 14 Feb 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Vauchamps6 | Battle | France | Emperor | Victory | 50–6 | [274] | |

| 17 Feb 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Mormans | Battle | France | Emperor | Victory | 51–6 | [275] | |

| 18 Feb 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Montereau | Battle | France | Emperor | Victory | 52–6 | [276] | |

| 7 Mar 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Craonne | Battle | France | Emperor | Victory | 53–6 | [277][278] | |

| 9–10 Mar 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Laon | Battle | France | Emperor | Defeat | 53–7 | [279][280] | |

| 13 Mar 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Reims | Battle | France | Emperor | Victory | 54–7 | [281] | |

| 20–21 Mar 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube | Battle | France | Emperor | Indecisive | 54–7 | [282][283] | |

| 26 Mar 1814 | War of the Sixth Coalition | Battle of Saint-Dizier | Battle | France | Emperor | Indecisive | 54–7 | [284] | |

| 16 Jun 1815 | Hundred Days | Battle of Ligny | Battle | Belgium | Emperor | Victory | 55–7 | [285][286] | |

| 18 Jun 1815 | Hundred Days | Battle of Waterloo | Battle | Belgium | Emperor | Defeat† | 55–8 | [287][288] |

Assessment

Napoleon thus won 55 battles when personally heading his army, with only 8 losses (8 remained indecisive) and none against a weaker force.

Notably, his last great adversary Arthur Wellesley won 35 and lost 6 battles (9 remained indecisive) in his lifetime.[289] Thus, Napoleon won 77% of his battles while Wellington won 70% of his.

Footnotes

- a Journées were notable days during the revolution, such as major riots which had significant political consequences.[290][291]

- b The French Republican Calendar, or French Revolutionary Calendar, was introduced on 22 September 1793, by the Convention, to commemorate a new era. "An II", meaning "Year II", is reference to the second year of the Republic, etc. It remained in use until 31 December 1805, 10 Nivôse An XIV (FRC).[292]

- c In terms of leadership, Murad Bey was a Mamluk military chieftain as Emir el-Hadj (prince or leader of the pilgrimage to Mecca), where Ibrahim Bey held the title Shiekh el-Beled (head or chief of the country); they ruled with de facto power.[293][294]

- x The Mamluk flag image design is speculative. The main source pointing to this design is the Catalan Atlas, which as a historical primary source cannot be considered a reliable reference.

- x1 Sources differ as to when the Battle of Mondovi took place. Fremont-Barnes (2006) states 19–21 April 1796,[195] Lachouque (1966) and Chandler (1966) state 21 April,[196][295] while Smith (1998) states 22 April.[197]

Notes

- Page numbers in italic denote a full-page illustration, map or table.

- ↑ Roberts says his losses came at Siege of Acre (1799), Battle of Aspern-Essling (1809), Battle of Leipzig (1813), Battle of La Rothière (1814), Battle of Laon (1814), Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube (1814), and Battle of Waterloo (1815). Andrew Roberts, "Why Napoleon merits the title 'the Great,'" BBC History Magazine (1 November 2014)

- ↑ Andrew Roberts, Napoleon: A Life (2014)

- ↑ Cronin, p. 20.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 39, 42–43.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 46.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 45.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 47.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Barnett, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 49–54.

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 12–14.

- ↑ Doyle, p. 68.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 36.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 35–41.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 61.

- ↑ Barnett, p. 25.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 62.

- ↑ Doyle, p. 114.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 93.

- 1 2 Cronin, p. 63.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 96–100.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 66–69.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 161.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 143.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 72.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 14.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 169–176.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 210.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 135–139.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 123–130.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 180–181.

- 1 2 Cronin, p. 76.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 185–189.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 193–195.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 193, 332.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 13–16.

- ↑ Ireland, p. 145.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 15.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Doyle, p. 224.

- ↑ Doyle, p. 202.

- ↑ Doyle, p. 204.

- ↑ Doyle, pp. 125, 127.

- ↑ Doyle, p. 265.

- ↑ Doyle, p. 244.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 194.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 201–203.

- 1 2 Doyle, p. 241.

- ↑ Doyle, p. 232.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 202.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 83.

- 1 2 Dwyer, p. 131.

- ↑ de Chair, pp. 59–70.

- ↑ Chandler (2002), p. 21.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 84.

- ↑ Chandler (2002), p. 22.

- ↑ Dwyer, pp. 122–123.

- 1 2 3 Dwyer, p. 138.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 85–86.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 20.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 139.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 136.

- ↑ Doyle, p. 254.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 87.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 222.

- 1 2 Cronin, p. 88.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 137.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 23.

- ↑ Ireland, p. 207.

- ↑ Ireland, pp. 262–263.

- ↑ Ireland, pp. 275–278.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 28.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 30.

- ↑ Doyle, pp. 247–271.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 221–248.

- ↑ Jones, pp. 115–212.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 264–268.

- ↑ Dwyer, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 34.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 156.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 157.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 97.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 99.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 168.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 171.

- ↑ Doyle, p. 321.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 283.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 281.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 172.

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 286.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), p. 42.

- ↑ Hibbert, pp. 286–288.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 40.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 177.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 179.

- ↑ Dwyer, p. 180.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 41.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 130–132.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 56.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 62.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 81–85.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 84.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 86.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 87.

- ↑ Chandler (2002), p. 27.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), p. 352.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 87–88.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 92–93.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 93.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 94.

- ↑ Hawthornthwaite (1995), pp. 102–103.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 95.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Cronin, pp. 147–149.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 96.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 97.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 98.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 101.

- ↑ Chandler (2002), p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Smith, p. 126.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 103.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 105.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 106.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 106–112.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 113.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 114.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 115.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 116–120.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 120.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), p. 382.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 121.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), p. 442.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), p. 89.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 122–124.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 125, 207.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 208–209.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 32.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 33.

- 1 2 Strathern, p. 44.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 212.

- ↑ Strathern, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Strathern, pp. 44, 47.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 47.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 215.

- ↑ Strathern, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 180.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 50.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 51.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 58.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 60.

- ↑ Strathern, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 65.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 66.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 69.

- ↑ Dyer, p. 365.

- ↑ Cronin, p. 178.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 67.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 74–76, 81.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 83.

- ↑ Asprey (2000), p. 263.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 222.

- ↑ Dwyer, pp. 368–369.

- ↑ Asprey (2000), p. 264.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 104.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 223.

- ↑ Strathern, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 109.

- 1 2 Chandler (1966), p. 224.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 128.

- ↑ Strathern, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 125.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 226.

- ↑ Smith, p. 63.

- ↑ Smith, p. 92.

- ↑ Smith, p. 111.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Smith, p. 112.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), pp. 86–87.

- 1 2 Fremont-Barnes, pp. 647–648.

- 1 2 Chandler (1999), pp. 283–284.

- 1 2 Smith, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), p. 153.

- ↑ Smith, p. 113.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 118–119, 124, 131–132.

- 1 2 Smith, p. 119.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Smith, p. 122.

- ↑ Smith, p. 123.

- 1 2 Smith, p. 127.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 14–16.

- ↑ Smith, p. 128.

- 1 2 Smith, p. 131.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Esposito, map 30.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), p. 8.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), p. 410.

- ↑ Smith, p. 140.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 150.

- ↑ Chandler (1966), p. 227.

- ↑ Smith, p. 145.

- ↑ Smith, p. 146.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Strathem, p. 352.

- ↑ Smith, p. 161.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Smith, p. 205.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 215–217.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 223–225.

- ↑ Smith, p. 234.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 241–243.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 249–251.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Smith, p. 271.

- ↑ Smith, p. 290.

- ↑ Smith, p. 291.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 291–293.

- ↑ Sutherland, p. 50.

- ↑ Smith, p. 293.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 307–310.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 318–322.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 54–56.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 387–388.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 390–392.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 397–398.

- 1 2 Smith, pp. 403–405.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 406–408.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 77–79.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 420–422.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Smith, p. 423.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 443–445.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 461–470.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 87–89.

- 1 2 Smith, p. 472.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 473–475.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 490–491.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 491–493.

- ↑ Sutherland, p. 94.

- ↑ Smith, p. 494.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 494–495.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Smith, p. 496.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 496–497.

- ↑ Smith, p. 498.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 498–499.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 507–508.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Smith, p. 510.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Smith, p. 511.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 512–513.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Fremont-Barnes, pp. 932–933.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 535–536.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Smith, pp. 538–548.

- ↑ Sutherland, pp. 106–109.

- ↑ Battle record of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

- ↑ Hibbert, p. 324.

- ↑ Jones, p. 415.

- ↑ Jones, pp. 425–429.

- ↑ Strathern, p. 110.

- ↑ Chandler (1999), pp. 205, 291.

- ↑ Lachouque, p. 40.

References

- Asprey, Robert (2000). The Rise and Fall of Napoleon Bonaparte: Volume I – The Rise. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0349112886.

- —— (2001). The Rise and Fall of Napoleon Bonaparte: Volume II – The Fall. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0349114842.

- Barnett, Correlli (1997) [First pub. 1978]. Bonaparte. Ware, UK: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1853266782.

- Chandler, David (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: The Macmillan Company. ISBN 978-0025236608.

- —— (1999). Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. Ware, UK: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1840222036.

- —— (2002) [First pub. 1973]. Napoleon. Barnsley, UK: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0850527506.

- Cronin, Vincent (1973). Napoleon. Harmondsworth, UK: Pelican Books. ISBN 978-0140217162.

- de Chair, Somerset, ed. (1992). Napoleon on Napoleon. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 978-1860198762.

- Doyle, William (2002). The Oxford History of the French Revolution (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199252985.

- Dwyer, Philip (2007). Napoleon: The Path to Power 1769–1799. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0747566779.

- Esposito, Brigadier General Vincent J.; Elting, Colonel John R. (1999) [First pub. 1964]. A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars (New ed.). London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1853673467.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, ed. (2006). The Encyclopedia of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1851096466.

- Haythornthwaite, Philip J. (1995) [First pub. 1988]. Napoleon's Military Machine. Staplehurst, UK: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1873376461.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1982). The French Revolution. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140049459.

- Ireland, Bernard (2006). The Fall of Toulon. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0304367269.

- Jones, Colin (1990) [First pub. 1988]. The Longman Companion to the French Revolution. Harlow, UK: Longman. ISBN 978-0582494176.

- Lachouque, Henry (French); Monkcom, Roy (translator) (1966) [First pub. 1964 in French]. Napoleon's Battles. London: George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0049440029.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1853672767.

- Strathern, Paul (2007). Napoleon in Egypt: The Greatest Glory. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0224076814.

- Sutherland, Jonathan (2003). Napoleonic Battles. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife. ISBN 978-1840374230.

- Taylor, Brian (2006). The Empire of the French. Stroud, UK: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1862272545.

Further reading

- Bell, David A. The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Warfare as We Know It (2008) excerpt and text search

- Bruce, Robert B. et al. Fighting Techniques of the Napoleonic Age 1792–1815: Equipment, Combat Skills, and Tactics (2008) excerpt and text search

- Chandler, David G. The Campaigns of Napoleon (1973) 1172 pp; a detailed guide to all major battles excerpt and text search

- Crowdy, Terry. Napoleon's Infantry Handbook (2015)

- Delderfield, R.F. //Imperial Sunset: The Fall of Napoleon, 1813-14 (2014)

- Duffy, Christopher (1999) [First pub. 1972]. Borodino and the War of 1812. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 978-0304352784.

- —— (1999) [First pub. 1977]. Austerlitz 1805. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 978-0304352791.

- Dupuy, Trevor N. and Dupuy, R. Ernest. The Encyclopedia of Military History (2nd ed. 1970) pp 730–770

- Dwyer, Philip. Napoleon: The Path to Power (2008) excerpt vol 1; Citizen Emperor: Napoleon in Power (2013) excerpt and text search v 2; most recent scholarly biography

- Elting, John R. Swords Around a Throne: Napoleon's Grand Armee (1988)

- Esdaile, Charles. Napoleon's Wars: An International History 1803-1815 (2008), 621pp

- Gates, David. The Napoleonic Wars 1803-1815 (NY: Random House, 2011)

- Griffith, Paddy. The Art of War of Revolutionary France, 1789–1802 (1998) excerpt and text search

- Harvey, Robert (2013). The War of Wars. Constable & Robinson. p. 328., well-written popular survey of these wars

- Haythornthwaite, Philip J. Napoleon's Military Machine (1995) excerpt and text search

- Hazen, Charles Downer. The French Revolution and Napoleon (1917) online free

- Kagan, Frederick W. The End of the Old Order: Napoleon and Europe, 1801-1805 (2007)

- McLynn, Frank. Napoleon: A Biography (1997)

- Nafziger, George F. The End of Empire: Napoleon's 1814 Campaign (2014)