Sonnet 130

| Sonnet 130 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

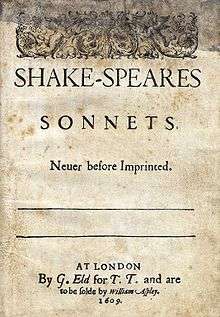

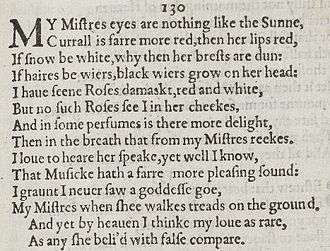

Sonnet 130 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

William Shakespeare's Sonnet 130 mocks the conventions of the showy and flowery courtly sonnets in its realistic portrayal of his mistress.

Synopsis

Sonnet 130 satirizes the concept of ideal beauty that was a convention of literature and art in general during the Elizabethan era. Influences originating with the poetry of ancient Greece and Rome had established a tradition of this, which continued in Europe's customs of courtly love and in courtly poetry, and the work of poets such as Petrarch. It was customary to praise the beauty of the object of one's affections with comparisons to beautiful things found in nature and heaven, such as stars in the night sky, the golden light of the rising sun, or red roses.[2] The images conjured by Shakespeare were common ones that would have been well-recognized by a reader or listener of this sonnet.

Shakespeare satirizes the hyperbole of the allusions used by conventional poets, which even by the Elizabethan era, had become cliché, predictable, and uninspiring. This sonnet compares the poet's mistress to a number of natural beauties; each time making a point of his mistress' obvious inadequacy in such comparisons; she cannot hope to stand up to the beauties of the natural world. The first two quatrains compare the speaker's mistress to aspects of nature, such as snow or coral; each comparison ending unflatteringly for the mistress. In the final couplet, the speaker proclaims his love for his mistress by declaring that he makes no false comparisons, the implication being that other poets do precisely that. Shakespeare's sonnet aims to do the opposite, by indicating that his mistress is the ideal object of his affections because of her genuine qualities, and that she is more worthy of his love than the paramours of other poets who are more fanciful.

Structure

Sonnet 130 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 1st line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; / × × / × / × / × / Coral is far more red than her lips' red: (130.1-2)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

This is followed (in line 2, scanned above) with a common metrical variation, the initial reversal. An initial reversal is potentially present in line 8, and mid-line reversals occur in lines 4 and 12, and potentially in line 3. The beginning of line 5 is open to interpretation: it may be regular or an instance of initial reversal; however, it is most naturally scanned with the rightward movement of the first ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

× × / / × / × / × / I have seen roses damask'd, red and white, (130.5)

If line 2's "her" is not given contrastive accent (as is assumed above), then "than her lips' red" would also form a minor ionic.

The meter demands that line 13's "heaven" function as one syllable.[3]

Analysis

Sonnet 130 as a satire

"This sonnet plays with poetic conventions in which, for example, the mistress's eyes are compared with the sun, her lips with coral, and her cheeks with roses. His mistress, says the poet, is nothing like this conventional image, but is as lovely as any woman".[4] Here, Barbara Mowat offers her opinion of the meaning behind Sonnet 130; this work breaks the mold to which Sonnets had come to conform. Shakespeare composed a sonnet which seems to parody a great many sonnets of the time. Poets like Thomas Watson, Michael Drayton, and Barnabe Barnes were all part of this sonnet craze and each wrote sonnets proclaiming love for an almost unimaginable figure;[5] Patrick Crutwell posits that Sonnet 130 could actually be a satire of the Thomas Watson poem "Passionate Century of Love", pointing out that the Watson poem contains all but one of the platitudes that Shakespeare is making fun of in Sonnet 130.[6] However, E.G. Rogers points out the similarities between Watson's "Passionate Century of Love," Sonnet 130, and Richard Linche's Poem collection entitled "Diella."[7] There is a great deal of similarity between sections of the Diella poem collection and Shakespeare's "Sonnet 130", for example in "130" we see, "If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head," where in "Diella" we see "Her hayre exceeds fold forced in the smallest wire."[8] Each work uses a comparison of hairs to wires; while in modern sense this may seem unflattering, one could argue that Linche's work draws upon the beauty of weaving gold and that Shakespeare mocks this with harsh comparison. This, along with other similarities in textual content, lead, as E.G. Rogers points out, the critic to believe that Diella may have been the source of inspiration for both homage, by Watson's "Passionate Century of Love," and satire by Shakespeare's "Sonnet 130." The idea of Satire is further enforced by final couplet of "130" in which the speaker delivers his most expositional line: "And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare, as any she belied with false compare." This line projects the message behind this work, demeaning the false comparisons made by many poets of the time.[9]

Sonnet 130: Complimentary/derisive nature

According to Carl Atkins, many early editors took the sonnet at face value and believed that it was simply a disparagement of the writer's mistress.[10] However, William Flesch believes that the poem is actually quite the opposite, and acts as a compliment. He points out that many poems of the day seem to compliment the object of the poem for qualities that they really don't have, such as snow white skin or golden hair.[11] He states that people really don't want to be complimented on a quality they don't have, e.g. an old person doesn't want to be told they are physically young, they want to be told they are youthful, in behavior or in looks. Flesch notes that while what Shakespeare writes of can seem derisive, he is in reality complimenting qualities the mistress truly exhibits, and he ends the poem with his confession of love.

Possible influences

Shakespeare and other great writers would reference each other and each other's works in their own writing. According to Felicia Jean Steele, Shakespeare uses Petrarchan imagery while actually undermining it at the same time.[12] Stephen Booth would agree that Shakespeare references Petrarchan works however, Booth says that Shakespeare "gently mocks the thoughtless mechanical application of the standard Petrarchan metaphors."[13] Felicia Steele and Stephen Booth agree that there is some referencing going on, they vary slightly in the degree of Shakespeare's mockery. Steele feels much stronger about the degree in which Shakespeare is discounting Petrarchan ideas by observing that in 14 lines of Sonnet 130, "Shakespeare seems to undo, discount, or invalidate nearly every Petrarchan conceit about feminine beauty employed by his fellow sonneteers." The final couplet is designed to undo the damage Shakespeare has done to his reader's faith that he indeed loves his "dusky mistress." Steele's article offers Stephen Booth's paraphrasing of the couplet: "I think that my love is as rare as any woman belied by false compare." Helen Vendler, who is also referenced in Steele's article states that the final couplet would read; "In all, by heaven, I think my love as rare/ As any she conceived for compare." All three of these authors; Steele, Booth, and Vendler believe that in this couplet, Shakespeare is responding to Petrarchan imagery because other sonneteers actively misrepresent, or "belie" their mistress' beauty.

See also

References

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ↑ Evans, Gwynne Blakemore (2006). The Sonnets. Cambridge University Press. p. 233. ISBN 9780521678377.

- ↑ Kerrigan 1995, p. 360.

- ↑ Mowat, Barbara A., and Paul Werstine, eds. Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York: Washington Square, 2004. Print.

- ↑ Quennell, P. Shakespeare: the Poet and his Background. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1964. Print

- ↑ Crutwell, Patrick. The Shakespearean Moment and its Place in the Poetry of the 17th Century. New York: Random House. 1960. Print

- ↑ Rogers, E.G., "Sonnet CXXX: Watson to Linche to Shakespeare." Shakespeare Quarterly. 11.2 (1960): 232-233. Print.

- ↑ Rogers, E.G., "Sonnet CXXX: Watson to Linche to Shakespeare." Shakespeare Quarterly. 11.2 (1960): 232-233. Print.

- ↑ Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, 1997

- ↑ Shakespeare, William, and Carl D. Atkins. Shakespeare's Sonnets: with Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 2007. Print.

- ↑ Flesch, William. "Personal Identity and Vicarious Experience in Shakespeare's Sonnets." Print. Rpt. in A Companion to Shakespeare's Sonnets. Ed. Michael Schoenfeldt. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2007. 383-401. Print.

- ↑ Steele, Felicia Jean. "Shakespeare Sonnet 130." Explicator 62. pp. 132-137. 2003

- ↑ Booth, Stephan. Shakespeare's Sonnets, Edited with Analytic Commentary. New Haven, 1977

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

.png)