Sonnet 28

| Sonnet 28 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

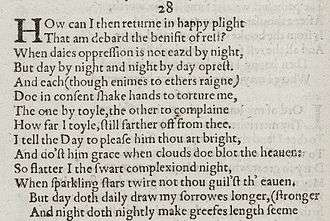

Sonnet 28 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 28 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare, it was first published in 1609. The sonnet is a part of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man — usually referred to as "the young man" or the "friend". Shakespeare's use of "friend" means more than just of a sexual nature, it highlights the Renaissance ideal of male fidelity and equality. From sonnets 18 to 126, Shakespeare writes about his relationship with the said young man.[2] Although the identity of the young man is still unknown, Henry Wriothesley and William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, are the two leading contenders.[2]

Sonnet 28 is a part of a five sonnet series that focuses on the poet reflecting upon his friend, in addition, there is a focus on night and sleeplessness, which is a traditional motif in Petrarchan sonnet sequences.[3] Moreover, Shakespeare infamously declares his "faithfulness of his love for the young man and celebrates the power of his poetry to preserve the young man's memory" in these sonnets.[2] Similar to Sonnet 27, Sonnet 28 ends comparably — in an unhappy state. The sonnet "turns on the indistinguishablity of day and night; they were both occasions of work in the former poem, but here they are both occasions of torture."[4]

Sonnet Structure

A sonnet is a poetic form, which typically consists of fourteen lines of rhymed, metrical verse.[2] Sonnet 28 follows the typical Shakespearean sonnet form; it consists of three quatrains (lines 1–12) and a couplet (lines 13–14). The Italian Petrarchan sonnet is suggested by the presence of a volta, which rhetorically separates the sonnet into an octave (8 lines) and a sestet (6 lines). Line 8 completes the first thought of the sonnet and a new direction is initiated in line 9. The rhyme scheme for all Shakespearean sonnets, including Sonnet 28 is: abab cdcd efef gg.[3] It is written in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. Line four clearly exemplifies the form's iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / But day by night and night by day oppress'd, (28.4)

The lines of the couplet, certainly, and lines ten and twelve, probably, have a final extrametrical syllable or feminine ending:

× / × / × / × / × / (×) But day doth daily draw my sorrows longer, (28.13)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

One of the most common patterns of pulsating alliteration is in b or p (the voiced and unvoiced forms of the same sound), in combination with a variety of r sounds. There are excellent examples in 28.2–3 (debarred, benefit of rest, oppression).[5] Shakespeare's poetic line is based less upon rigid syllable counts than on a careful arrangement of stresses within an understood metrical norm, as one might expect from a poet who had written both for the theater and for the page. It aspires to set up expectations that it deliberately either fulfills or frustrates.[6]

Glossary

How can I then return in happy plight, A Cheerful condition[7] That am debarred the benefit of rest? B Excluded or shut out from a place or condition[7] When day's oppression is not eas'd by night, A But day by night and night by day oppress'd, B And each, though enemies to either's reign, C Do in consent shake hands to torture me, D The one by toil, the other to complain C How far I toil, still farther off from thee. D Always gettings farther[8] I tell the day, to please him thou art bright, E And dost him grace when clouds do blot the heaven: F So flatter I the swart-complexion'd night, E Black-faced[7] When sparkling stars twire not thou gild'st the even. F To twinkle[7] / To make the evening golden[7] But day doth daily draw my sorrows longer, G To draw out, extend[7] And night doth nightly make grief's length seem stronger. G

Context

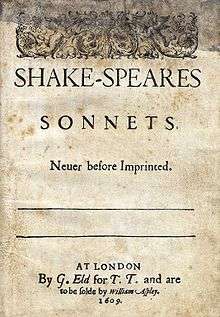

The exact dates in which Shakespeare composed Sonnet 28 and the Fair Youth sequence as a whole remain unclear. Provoked by William Jaggard's The Passionate Pilgrim, it seems plausible that Shakespeare may have prepared a collection of his sonnets in 1599, and that at one time had planned to publish it.[9] Furthermore, it is likely that at least some of the sonnets were circulating in manuscript before the release of the 1609 Quarto (or, "Q").

Scholars believe that Q was published in an unauthorized manner, and was subsequently suppressed soon after its initial publication, though there is no strong evidence to support the claim. According to scholar Katherine Duncan-Jones, the origins surrounding the belief that Q was suppressed can be ascertained "by anxieties felt by British scholars who worked in the aftermath of the infamous Labouchere Amendment of 1885, which criminalized homosexual acts between consenting adult males."[10]

The majority of the biographical speculation pertaining to Sonnet 28 focuses on the identity of the young man. Although the man is never identified by his proper name, there have long been two leading contenders, both of whom were English Renaissance noblemen. According to scholar Robert Matz, "this has been assumed since the young man of the sonnets appears to be of higher birth than Shakespeare [and also for the reason that] poets in the English Renaissance often wrote or dedicated their poems to aristocratic men or women, because of the potential for prestige and literary patronage that writing for an aristocrat brought."[2]

Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, is first of the two noblemen under consideration, as scholars point to the fact that Shakespeare dedicated Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece specifically to him. Furthermore, details surrounding Wriothesley's personal life are also compatible and support this claim. For instance, around the time Shakespeare may have been starting to write the sonnet sequence, Wriothesley (like the man of the sonnets), was refusing marriage, and, according to Robert Matz, "another poet had already composed a poem for the earl that implicitly counseled him to do so. Shakespeare might have followed suit."[2] The second candidate is William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, though Shakespeare never dedicated any poetry to him; moreover, there is no direct evidence that Shakespeare even knew Herbert. However, the first compilation of Shakespeare's plays, published posthumously in 1623, was dedicated to William Herbert and his brother Philip. It is possible that the two men who wrote the dedication (actors and friends of Shakespeare) may have been aware of a relationship between him and Herbert.[2]

Peter Hyland contends that "the most controversial question to have haunted the history of the reception of the Fair Youth sequence has concerned the nature of the love expressed for their youthful subject."[11] However, it is ultimately unknown whether the Sonnets demonstrate Shakespeare's sexual identity, or are simply evidence of his ability to convincingly evoke a range of erotic desires. According to Michael Schoenfeldt, "certainly the emotions articulated in many of the poems feel authentic. But this may just be a measure of the poet's art."[6] In any case, by rejecting the redundancy of mistress-worship (a characteristic common to Petrarchan sonnets) Shakespeare sought to re-conceptualize the sonnet genre; thus creating, according to Katherine Duncan-Jones, "a sonnet sequence so different from all its predecessors that the form could never be the same again."[3] Ultimately, scholars concede that because they do not know any intimate details of Shakespeare's life, the sonnets may not be autobiographical at all - nor can they place the poems by public events, for there is no clear and undisputed reference. Therefore, readers and scholars alike cannot be sure whether Pembroke or Wriothesley served as a source of inspiration for the Fair Youth sequence and Sonnet 28 in particular.[12]

Exegesis

Like Sonnet 27, this poem focuses on the indistinguishable of day and night. However, in the former poem, day and night are both occasions of work or toil, whereas Sonnet 28 employs them as occasions of torture. Although day and night are oppositional they have now become allies and, in consent, shake hands to torture the poet. Because of his absence from the beloved, the poet's "personified days and nights" wreak their vengeance upon him. The poet in turn attempts to placate his torturers by assuring them that they, unlike himself, are always in the presence of the beloved. Conversely, "day and night refuse to believe such sophistry, and their torture goes on."[4]

Dympna Callaghan asserts that the sonnet describes how "the agonies of separation from the addressee [have taken] their toll on the poet" and how "there is a narrative and structural continuity between this sonnet and the preceding one, which again addresses the torment of insomnia...however, it is desire rather than guilt that induces sleeplessness. Exhausted by his work during the day and tortured again with sleeplessness at night, his turmoil is compounded and his grief at separation only intensifies."[13]

In lines 1-8 the poet wonders how he could possibly return to a happy from his travels as he is oppressed by the toil of work during the day, while emotionally and psychologically tortured by visions of the beloved by night. The cycle of misery is represented by the repetition of 'day…oppression…night…day…night…night…day…oppressed' in lines 3-4. Day and night are, in effect, "tyrants ruling his own kingdom, each the enemy of the other, and encroaching on the other's boundaries." This personification of tyranny is exhibited when the two kings "shake hands" in line 6; they make a truce to join in torturing the poet. Day tortures the poet "by the toil of travel (27.1), and night tortures him to moan that the farther he goes as he toils, the farther he is from his beloved."[14]

In lines 9-12, the poet attempts to quell the torment of day and night by using flattery. In line 9, when the poet writes "when I tell the day, to please him thou art bright", 'him' is indicative of the day while 'thou' is the beloved. Another example of flattery can be observed in line 10, when the poet assures day that he is not dull "because the beloved’s brightness makes him beautiful, gracing him." Furthermore, when the evening sky appears grim and starless, the poet uses flattery by telling him that evening is "gilded by the beloved." In lines 11 and 12, the word "'night', not 'evening', is required by logic, but 'even' is imposed by rhyme" – a proclamation that "the evening star is the brightest star in the sky."[14] Furthermore, the poet again attempts to appease his torturers in line 11 by referring to night as 'swart-complexioned'. The poet's adulation is counterfeit, as he knows that a starless night is unattractive, but this admission enables Shakespeare to "insert into the poem a flash of praise of the beloved, whose brightness graces a dull day and gilds a dull evening."[14]

Nonetheless, lines 13-14 indicate that the torturers are not affected by flattery. In line 13, day protracts the work-weary poet's sorrows, while the barren solitude of night makes his suffering seem more intense. Once more, as in lines 3-4, David West posits that "repetition represents the misery of separation, drudgery, and insomnia, with 'day' and 'night' in lines 9 and 11 followed by 'day doth daily', 'night doth nightly', all made to seem even longer by the repeated rhymes in lines 1,3,9, and 11, and the extra syllable at the end of 10 and 12. Every day of his absence prolongs his misery, and every long night makes his misery more acute."[14]

Notes

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Matz, Robert (2008). The World of Shakespeare's Sonnets: An Introduction. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 5–8.

- 1 2 3 Shakespeare, William; Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: AS. pp. 96–103.

- 1 2 Vendler, Helen (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP. pp. 157–159.

- ↑ Booth, Stephanie (1977). Shakespeare's Sonnets. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 200.

- 1 2 Schoenfeldt, Michael (2010). Cambridge Introduction to Shakespeare's Poetry. Cambridge, GBR: Cambridge University Press. p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shakespeare, William; Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: AS. p. 166.

- ↑ Ingram, W.G.; Redpath, Robert Theodore Holmes (1964). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: University of London Press. p. 70.

- ↑ Shakespeare, William; Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: AS. p. 3.

- ↑ Shakespeare, William; Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: AS. p. 31.

- ↑ Hyland, Peter (2003). An Introduction to Shakespeare's Poems: Reading Shakespeare's Sonnets: 1. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 159.

- ↑ Beckwith, Elizabeth (1926). "On the Chronology of Shakespeare's Sonnets". The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. 25 (2): 242.

- ↑ Callaghan, D (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 112–113.

- 1 2 3 4 West, David (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With a New Commentary. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. pp. 98–99.

References

- Baldwin, T. W. On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.

- Beckwith, Elizabeth. "On the Chronology of Shakespeare's Sonnets." The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 25.2, 1926.

- Callaghan, D. “Appendix: The Matter of the Sonnets.” Shakespeare's Sonnets, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, UK. 2007.

- Hubler, Edwin. The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

- Hyland, Peter. "Reading Shakespeare's Sonnets: 1." An Introduction to Shakespeare's Poems. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

- Matz, Robert. "Introduction." The World of Shakespeare's Sonnets: An Introduction. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2008.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael. Cambridge Introduction to Shakespeare's Poetry. Cambridge, GBR: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Shakespeare, William, and David West. Shakespeare's Sonnets: With a New Commentary. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co, 2007.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)