Sonnet 4

| Sonnet 4 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

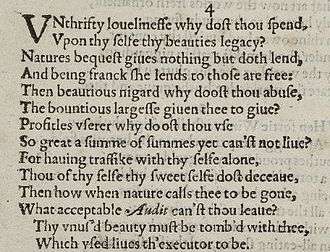

Sonnet 4 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 4 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the Fair Youth sequence.

Synopsis

Shakespeare urges the man to have children, and thus not waste his beauty by not creating more children. To Shakespeare, unless the male produces a child, or “executor to be", he will not have used nature's beauty correctly. Shakespeare uses business terminology ("niggard", "usurer", "sums", "executor", "audit", "profitless") to aid in portraying the young man's beauty as a commodity, which nature only "lends" for a certain amount of time.

- Nature's bequest gives nothing but doth lend,

- And being frank she lends to those are free

Shakespeare finishes with a warning of the fate of he who does not use his beauty:

- Thy unused beauty must be tomb'd with thee,

- Which, used, lives th' executor to be.

The Speaker begins Sonnet 4 (quatrain 1) by asking his male friend why he must waste his beauty on himself, because nature doesn’t give people gifts besides the ones we get at birth. However, nature does lend to those who are generous with their own beauty. The second quatrain is about the speaker asking a friend, the subject of the poem, why he abuses the plentiful and generous gifts he was given, which are meant to be shared with others. Then the speaker goes on to ask why he vows to be a bad shareholder, using up what he has to offer but not able to care for himself or reserve his own money. One literary piece sums this up as the "idea of miser versus money-lender".[2] This is questioning whether or not he should loan money. Should he be a lender or should he keep from giving his money away, coming off as a miser. In quatrain 3, the speaker is trying to persuade his male friend to have children because he says that not doing so would be a waste of the man’s beauty. The speaker says that there is no reason why his friend should remain alone and let his beauty die off with him. Joseph Pequigney said that Shakespeare's sonnets have "erotic attachment and sexual involvement with the fair young man with whom all of sonnets 1-126 are concerned".[3] Sonnet 4 clearly is a part of this group and does indeed have some references that can be taken as emotional descriptions. The couplet suggests that the young man has valuable attraction that is not being used properly or appreciated.

Basic structure and rhyme scheme

The rhyme scheme of the sonnet is abab cdcd efef gg, the typical rhyme scheme for an English or Shakespearean sonnet. There are three quatrains and a couplet which serves as an apt conclusion. The fourth line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter line:

× /× / × / × / × / And being frank, she lends to those are free (4.4)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Themes, imagery, and specific character(s)

Sonnet 4 is one of the procreation sonnets, which are sonnets 1–17. This sonnet, as well, is focused on the theme of beauty and procreation. The characters of Sonnet 4 are the speaker and his good friend (known as the young man). In the book A Companion to Shakespeare's Sonnet, edited by Michael Schoenfeldt, Shakespeare critic Schoenfeldt describes the differences in the way the speaker and the young man are portrayed in procreation sonnets, saying "The desiring male subject (the speaker) has a clear, forceful voice... But the desired male object (the young man) in the sonnets has no voice".[4] This certainly holds true in Sonnet 4 as the speaker addresses the young man the entire time with the young man's voice never being heard.

Later in the same book, an essay from Shakespeare critic Garret A. Sullivan Jr. describes the relationship between the speaker and the young man which is seen in sonnet four, saying "The young man of the procreation sonnets, then, is the object of admonition; the poet (speaker) urgently seeks to make him change his ways, and, as we shall see does so in the intertwined names of beauty and memory and in the face of oblivion".[5] Sonnet Four follows these very themes with the speaker praising his friend, the young man, for his beauty, he moves on to say that his friend not having children would be inexcusable, when he says "Then how when nature calls thee to be gone: What acceptable audit canst though leave?" (lines 11–12) Here the speaker is using the unpredictability of nature to try to convince his friend to hurry up and have children. He also tries to appeal to his friend's emotions by saying, "For having traffic with thyself alone, / Thou of thyself thy sweet self dost deceive" (lines 9-10). The speaker is saying that is wrong and deceives the friend's own self if he decides to remain single and childless. Line 11 also contains a sexually suggestive play on words when the speaker says "having traffic with thyself alone". The idea of being alone is used by the speaker as being the pathetic alternative to marrying and having a family.

The speaker seems to personify nature in the first quatrain in saying: "Nature's bequest gives nothing, but doth lend, / And being frank, she lends to those are free" (lines 3–4). The speaker is saying that nature gives gifts at birth, and calls on people, giving something inhuman human-like characteristics. Several words in the sonnet; such as "bequest", "usurer" and "sum"; also make explicit the accounting motif of the prior sonnets.[6] The couplet sums up with a potential answer to all of the questions that the author was posing throughout the entire sonnet. He says, "thy unused beauty must be tombed with thee" in the first line of the couplet. This is suggesting that the young man has valuable attraction that is not being used properly or appreciated. It seems as if the speaker is insinuating that the beauty will die with the young man. The last line of the couplet says, "which usèd, lives th'executor to be." Here it seems as if the speaker is saying that if the young man uses his beauty, then it will prolong his life. The word "executor" hints at both death and accounting.

Outside literary criticism

Many critics seem to agree with H.E. Rollins that Shakespeare's Sonnets "provide direct evidence concerning Shakespeare's private life".[7] Even Horace Furness seems to think that the "absurdities" found in the grammar of the couplet in Sonnet 4 may have used as tactics of emphasizing a message to the reader and addressee.[8] He says that they pose questions that "are more easily asked than answered".[9] There was even a scholar who posed the idea that the sonnets are divided into "two groups: all those which suggest moral irregularities are 'dramatic'; the rest are written in Shakespeare's own person".[10] There is no doubt that Shakespeare has one major if not many messages that he is sending to the world through his sonnets. Sonnet four is a prime example.

- "Use"

One of the major themes throughout Quatrain 2 of Sonnet 4, as well as in a few other Procreation Sonnets, is the variations of "use", as noticed by Halpern.[11] Krieger points out that this repetition of the various forms of "use" are also seen in Sonnets 6 and 9.[12] Critics take the repetition of different forms of "use" to mean many different things. It is pointed out by one critic that "the procreation sonnets display with particular brilliance Shakespeare's ability to manipulate words which in his language belonged both to the economic and the sexual/biological semantic fields".[13] This is definitely applicable to the word and manipulation of the word "use". In terms of sexuality, it is commonly thought that the speaker is "advising the young man on the proper 'use' of his semen".[14] The same critic also interprets the sonnet as the man misusing his semen by masturbating. Seen throughout many of the Procreation Sonnets is the idea that "the proper 'use' of semen involves not the creation of life as such but the creation of beauty".[15] The sonnet may not only be referencing masturbation though, the "language of usury in the procreation sonnets [is a language that] has strong associations with both prostitution and sodomitical relations".[16] There is, however, an economic aspect as well, changing the connotation of the quatrain. "Usury may denote a specific economic practice," but also at this time, "it [meant] all that seemed destabilizing and threatening in the socioeconomic developments affecting early modern England".[17]

- Sexuality

There are some fairly widespread questions as to whether or not the speaker may have a homosexual love interest in his friend the young man. This idea is hard to prove one way or the other but has been acknowledged by many writers and scholars such as Professor Robert Matz from George Mason University. It is difficult to tell if the speaker has a genuine respect and admiration for his friend or if there is more to it than that. However, this debate always comes down to personal opinions and it is up to the reader to decide what they would like to believe. Shakespeare uses many descriptions in this sonnet that are interpreted as sexual references. Renowned Shakespeare critic Joseph Pequigney writes in his book Such is my Love that line 10, "makes the most open reference to auto-eroticism. Being infecund, it involves both the expenditure of seed for self-gratification and withholding it from reproduction".[18] As Pequigney explains, in this sonnet not only is the speaker trying to convince his friend the young man to have children, but he is making an argument against masturbation, which is something the speaker sees as selfish and a waste of the young man's great genetics. This line also contributes to the reason why this sonnet has been called "A Disquisition Forbidding Masturbation" by Joseph Pequigney.[19] This subject of masturbation goes hand in hand with the idea of being alone and dying without producing children or heirs, something which the speaker thinks would be a selfish act and would deprive the future earth of beauty.

- Beauty

Joseph Pequigney said that Shakespeare's sonnets have "erotic attachment and sexual involvement with the fair young man with whom all of sonnets 1-126 are concerned".[20] Sonnet 4 clearly is a part of this group and does indeed have some references that can be taken as emotional descriptions. However, many critics seem to think that sonnet 4 is an exception in the sense that it points something much deeper than sexual attachments. Pequigney states that the sonnet "correlate economic and carnal operations, and it abounds in inconsistencies".[21] These inconsistencies that Pequigney mentions are things like "unthrifty beauty" is later then "beauteous niggard" and how this "'profitless user' who invests large 'sums' yet cannot 'live'".[22] They allow for the following description of the Youth: One that can "at one and the same time be a prodigal and a miser, can be extravagant with himself yet unable to 'live in posterity,' and can utilize while refraining from utilizing the sexuality of his fetching self".[23] This complexity is what creates a "transmission of beauty" and, according to Pequigney, this is what makes "the masturbation" unacceptable.[24] Simon Critchley says that the meaning of the couplet is that "if you don't reproduce you can leave no acceptable audit".[25] He evens compares Sonnet 4 to The Merchant of Venice in which Shakespeare is trying to emphasize themes concerning "increase, contract, abundance, waste, 'niggarding,' or miserliness".[26] This can be seen in the aforementioned complexities described by Pequigney. It seems as if the Speaker is insinuating that the beauty will die with the young man. This idea is reinforced by Joyce Stuphen who says that "In sonnet 4, it is nature that 'calls thee to be gone' and demands the 'acceptable audit'".[27] Therefore, the couplet seems to sum up the complexity of the sonnet with a proclaimed consequence.

Notes

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ↑ (Baldwin, T. W. On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.)

- ↑ (Pequigney, Joseph. "Such Is My Love: A Study of Shakespeare's Sonnets." Shakespeare Quarterly 38.3 (1987): 375-77. JSTOR. Web. 2 Mar. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2870514>.)

- ↑ (Schoenfeldt , Michael, ed. A Companion to Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Print.)

- ↑ (Schoenfeldt, 332)

- ↑ Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 4". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ↑ (Rollins, H.E. "Shakespeare: Sonnets." The Review of English Studies 1.3 July (1950): 255-58. JSTOR. Web. 2 Mar. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/510367>.)

- ↑ (Furness, Horace H. "A Concordance to Shakespeare's Poems: An Index to Every Word Therein Contained." North American Review 119.245 Oct. (1874): 436-42. JSTOR. Web. 2 Mar. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/25109868>.)

- ↑ (Furness 1874)

- ↑ (Pequigney 1987)

- ↑ (Halpern, Richard. Shakespeare's Perfume: Sodomy & Sublimity in the Sonnets, Wild, Freud, and Lacan. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002. Print.)

- ↑ (Krieger, Murray. A Window to Criticism: Shakespeare's Sonnets and Modern Poetics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1964.)

- ↑ (Greene, Thomas M. "Pitiful Thrivers: Failed Husbandry in the Sonnets." The Vulnerable Text: Essays on the Renaissance Literature. New York: Columbia UP, 1986. 175-93.)

- ↑ (Halpern 20)

- ↑ (Halpern 20)

- ↑ (Schoenfeldt 337)

- ↑ (Herman, Peter C. "What's the Use? Or, The Problematic of Economy in Shakespeare's Procreation Sonnets." Shakespeare's Sonnets: Critical Essays. Ed. James Schiffer. 1999. 265-270. Print.)

- ↑ (Pequigney, Joseph. Such Is My Love: A Study of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1985. Print.)

- ↑ (Pequigney 1987)

- ↑ (Pequigney 1987)

- ↑ (Pequigney 15)

- ↑ (Pequigney 15)

- ↑ (Pequigney 15-16)

- ↑ (Pequigney 16)

- ↑ (Critchley, Simon, and Tom McCarthy. "Universal Shylockery: Money and Morality in the "Merchant of Venice"." Diacritics 34.1 (2004): 2-17. JSTOR. Web. 26 Apr. 2012. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3805828.)

- ↑ (Critchley 9)

- ↑ (Stuphen, Joyce. Shakespeare's Sonnets: Critical Essays. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1999. 205-06. Print.)

References

- Baldwin, T. W. On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.

- Bernard, John D. "To Constancie Confin'de": The Poetics of Shakespeare's Sonnets. PMLA, Vol. 94, No. 1 (Jan., 1979), pp. 77–90.

- Critchley, Simon, and Tom McCarthy. "Universal Shylockery: Money and Morality in the "Merchant of Venice"." Diacritics 34.1 (2004): 2-17. JSTOR. Web. 26 Apr. 2012. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3805828.

- Crosman, Robert. "Making Love out of Nothing at All: The Issue of Story in Shakespeare's Procreation Sonnets." Shakespeare Quarterly 41.4 (1990): 470-88. JSTOR. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/

- Furness, Horace H. "A Concordance to Shakespeare's Poems: An Index to Every Word Therein Contained." North American Review 119.245 Oct. (1874): 436-42. JSTOR. Web. 2 Mar. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/25109868>.

- Greene, Thomas M. “Pitiful Thrivers: Failed Husbandry in the Sonnets.” The Vulnerable Text: Essays on the Renaissance Literature. New York: Columbia UP, 1986. 175-93.

- Halpern, Richard. Shakespeare’s Perfume: Sodomy & Sublimity in the Sonnets, Wild, Freud, and Lacan. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002. Print.

- Herman, Peter C. “What’s the Use? Or, The Problematic of Economy in Shakespeare’s Procreation Sonnets.” Shakespeare’s Sonnets: Critical Essays. Ed. James Schiffer. 1999. 265-270. Print.

- Hubler, Edwin. The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

- Hugh McIntosh. "The Social Masochism of Shakespeare's Sonnets." SEL Studies in English Literature 1500-1900 50.1 (2009): 109-25. Project MUSE. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. <http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/studies_in_english_literature/v050/50.1.mcintosh.html>.

- Krieger, Murray. A Window to Criticism: Shakespeare’s Sonnets and Modern Poetics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1964.

- Matz, Robert. "The Scandals of Shakespeare's Sonnets." ELH 77.2 (2010): 477-508. Project MUSE. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. <http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/elh/v077/77.2.matz.html>.

- Pequigney, Joseph. Such Is My Love: A Study of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1985. Print.

- Pequigney, Joseph. "Such Is My Love: A Study of Shakespeare's Sonnets." Shakespeare Quarterly 38.3 (1987): 375-77. JSTOR. Web. 2 Mar. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2870514>.

- Rollins, H.E. "Shakespeare: Sonnets." The Review of English Studies 1.3 July (1950): 255-58. JSTOR. Web. 2 Mar. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/510367>.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael, ed. A Companion to Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2007. Print.

- Scott, Alison V., 1974-. "Hoarding the Treasure and Squandering the Truth: Giving and Possessing in Shakespeare's Sonnets to the Young Man." Studies in Philology 101.3 (2004): 315-331. Project MUSE. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>.

- Stapleton, M. L. "Making the Woman of Him: Shakespeare's Man Right Fair as Sonnet Lady." Texas Studies in Literature and Language 43 (2001): 283-85. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. <http://muse.jhu.edu.ezp.slu.edu/journals/texas_studies_in_literature_and_language/v046/46.3stapleton.html>.

- Stuphe Stuphen, Joyce. Shakespeare's Sonnets: Critical Essays. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1999. 205-06. Print.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

Works related to Sonnet 4 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource

Works related to Sonnet 4 (Shakespeare) at Wikisource- An explanation of terminology in the sonnet

.png)