Sonnet 88

| Sonnet 88 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

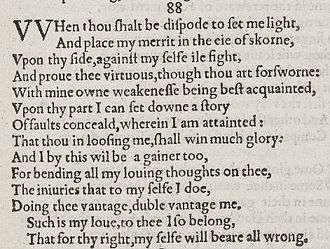

Sonnet 88 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| |||||||

Sonnet 88 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It's a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

Synopsis

When you criticise me, I will agree with your criticisms, and support your virtue, even though you have betrayed me. Knowing my own faults, I can be so convincing when I describe them, that you will be vindicated. Even I will win, because my love for you is such that any gain to you, gains me even more. I care about you so much that to help you I will harm myself.

Structure

Sonnet 88 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form, abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 1st line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / When thou shalt be disposed to set me light, (88.1)

Each line of the second quatrain has a final extrametrical syllable or feminine ending:

× / × / × / × / × /(×) That thou in losing me shalt win much glory: (88.8)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

The meter demands that line 4's "virtuous" function as 2 syllables.[2]

Analysis and criticism

The key to a full understanding this sonnet is found in the words "gainer" and "vantage". The speaker envisages an inevitable (i.e. "When"), vigorous and adversarial incident between the sonnet's "I" and the addressee, "thou". This conflict is established by the words "scorn", "side", "fight", "losing", "win", "gainer", "vantage" and "double-vantage". At first sight the sonnet's final couplet seems to confirm a subservience of the speaker to the addressee which was apparently established earlier in the sonnet and earlier in the sequence. In 1963 Martin Seymore-Smith said of this sonnet, [3] "Not only does Shakespeare intend to love to the bitter end, but also he proposes to demolish the edifice of his own ego by this process of identification with the Friend" and that if we do not understand this "we have little chance of understanding the Sonnets as a whole." However, such an interpretation has been shown to be simplistic and erroneous. Far from being a loser, the speaker becomes a covert winner by gaining the "double-vantage". In 1924 T.G. Tucker[4] noted that "double-vantage" is from tennis, and apparently means that I, your opponent, myself get "vantage" every time I thus yield it to you". In 2009 Fred Blick[5] established by detailed argument, based on historical research into the Real Tennis of Shakespeare's time, that "double-vantage" meant a win i.e. two vantage points in succession after a score of deuce (reflected in the sonnet's number 8 – 8) to win a "set", just as it means today. The word "set" then also meant a bet or stake (see OED, v. B. trans., 14, and the Fool in King Lear, "Set less than thou throwest", presumably at dice, I, iv, 123). Tennis was in Shakespeare's day almost always played as a gamble or "set", hence the origin of the scoring call "game and set". This casts a new light on the typically Shakespearean resonance of the words in line 1, "set me light" (bet against me at scornful odds) and line 6, "set down". Fred Blick has also shown that after sonnet 88 the speaker of the sonnets becomes more critical of the addressee and less subservient to him. Sonnet 126, at the end of the Fair Youth sequence, finally condemns to mortality the "lovely boy" as a mere human, no more than an equal of the mortal speaker. Perceptive as to structure, Helen Vendler[6] did note in 1997 that the "doubling vantage that is the theme of the sestet of 88 helps to organize the whole Sonnet", but extremely valuable as her comments are, she did not observe the existence of the important tennis metaphor nor its relevance to the whole sequence.

References

- ↑ Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- ↑ Booth 2000, p. 292.

- ↑ Martin Seymour-Smith, ed., Shakespeare's Sonnets, (London: Heinemann, 1963), 156.

- ↑ T.G. Tucker, The Sonnets of Shakespeare, Cambridge University Press, 1924, 165

- ↑ Fred Blick, "Duble Vantage", Tennis and Sonnet 88, The Upstart Crow, (Vol. XXVIII, Clemson University, 2009, 83-90)

- ↑ Helen Vendler, The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 1997, 385-386.

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)