Calcifediol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

(6R)-6-[(1R,3aR,4E,7aR)-4-[(2Z)-2-[(5S)-5- Hydroxy-2-methylidene-cyclohexylidene] ethylidene]-7a-methyl-2,3,3a,5,6,7-hexahydro- 1H-inden-1-yl]-2-methyl-heptan-2-ol | |

| Other names

25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 25-Hydroxycholecalciferol Calcidiol | |

| Identifiers | |

| 19356-17-3 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:17933 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL1222 |

| ChemSpider | 4446820 |

| DrugBank | DB00146 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.039.067 |

| 6921 | |

| MeSH | Calcifediol |

| PubChem | 5283731 |

| UNII | T0WXW8F54E |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C27H44O2 | |

| Molar mass | 400.64 g/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| A11CC06 (WHO) | |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

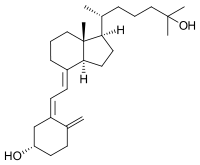

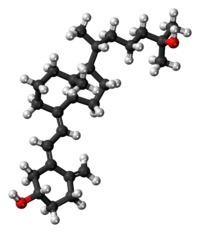

Calcifediol (INN), also known as calcidiol, 25-hydroxycholecalciferol, or 25-hydroxyvitamin D (abbreviated 25(OH)D),[1] is a prehormone that is produced in the liver by hydroxylation of vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) by the enzyme cholecalciferol 25-hydroxylase which was isolated by Michael F. Holick. Physicians worldwide measure this metabolite to determine a patient's vitamin D status.[2] At a typical daily intake of vitamin D3, its full conversion to calcifediol takes approximately 7 days.[3]

Calcifediol is then converted in the kidneys (by the enzyme 25(OH)D-1α-hydroxylase) into calcitriol (1,25-(OH)2D3), a secosteroid hormone that is the active form of vitamin D. It can also be converted into 24-hydroxycalcidiol in the kidneys via 24-hydroxylation.[4][5]

Blood test

In medicine, a 25-hydroxy vitamin D (calcifediol) blood test is used to determine how much vitamin D is in the body.[6] The blood concentration of calcifediol is considered the best indicator of vitamin D status.[7]

This test can be used to diagnose vitamin D deficiency, and it is indicated in patients with high risk for vitamin D deficiency and when the results of the test would be used as supporting evidence for beginning aggressive therapies.[8] Patients with osteoporosis, chronic kidney disease, malabsorption, obesity, and some other infections may be high risk and thus have greater indication for this test.[8] Although vitamin D deficiency is common in some populations including those living at higher latitudes or with limited sun exposure, the 25(OH)D test is not indicated for entire populations.[8] Physicians may advise low risk patients to take over-the-counter vitamin D in place of having screening.[8]

It is the most sensitive measure,[9] though experts have called for improved standardization and reproducibility across different laboratories.[7] According to MedlinePlus, the normal range of calcifediol is 30.0 to 74.0 ng/mL.[6] The normal range varies widely depending on several factors, including age and geographic location. A broad reference range of 20–150 nmol/L (8-60 ng/ml) has also been suggested,[10] while other studies have defined levels below 80 nmol/L (32 ng/ml) as indicative of vitamin D deficiency.[11]

US labs generally report 25(OH)D levels as ng/mL. Other countries often use nmol/L. Multiply ng/mL by 2.5 to convert to nmol/L.

Clinical significance

Increasing calcifediol levels are associated with increasing fractional absorption of calcium from the gut up to levels of 80 nmol/L (32 ng/mL). Urinary calcium excretion balances intestinal calcium absorption and does not increase with calcifediol levels up to ~400 nmol/L (160 ng/mL).[12]

A study by Cedric F. Garland and Frank C. Garland of the University of California, San Diego analyzed the blood from 25,000 volunteers from Washington County, Maryland, finding that those with the highest levels of calcifediol had a risk of colon cancer that was one-fifth of typical rates.[13] However, randomized controlled trials failed to find a significant correlation between vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colon cancer.[14]

A 2012 registry study of the population of Copenhagen, Denmark, found a correlation between both low and high serum levels and increased mortality, with a level of 50–60 nmol/L being associated with the lowest mortality. The study did not show causation.[15][16]

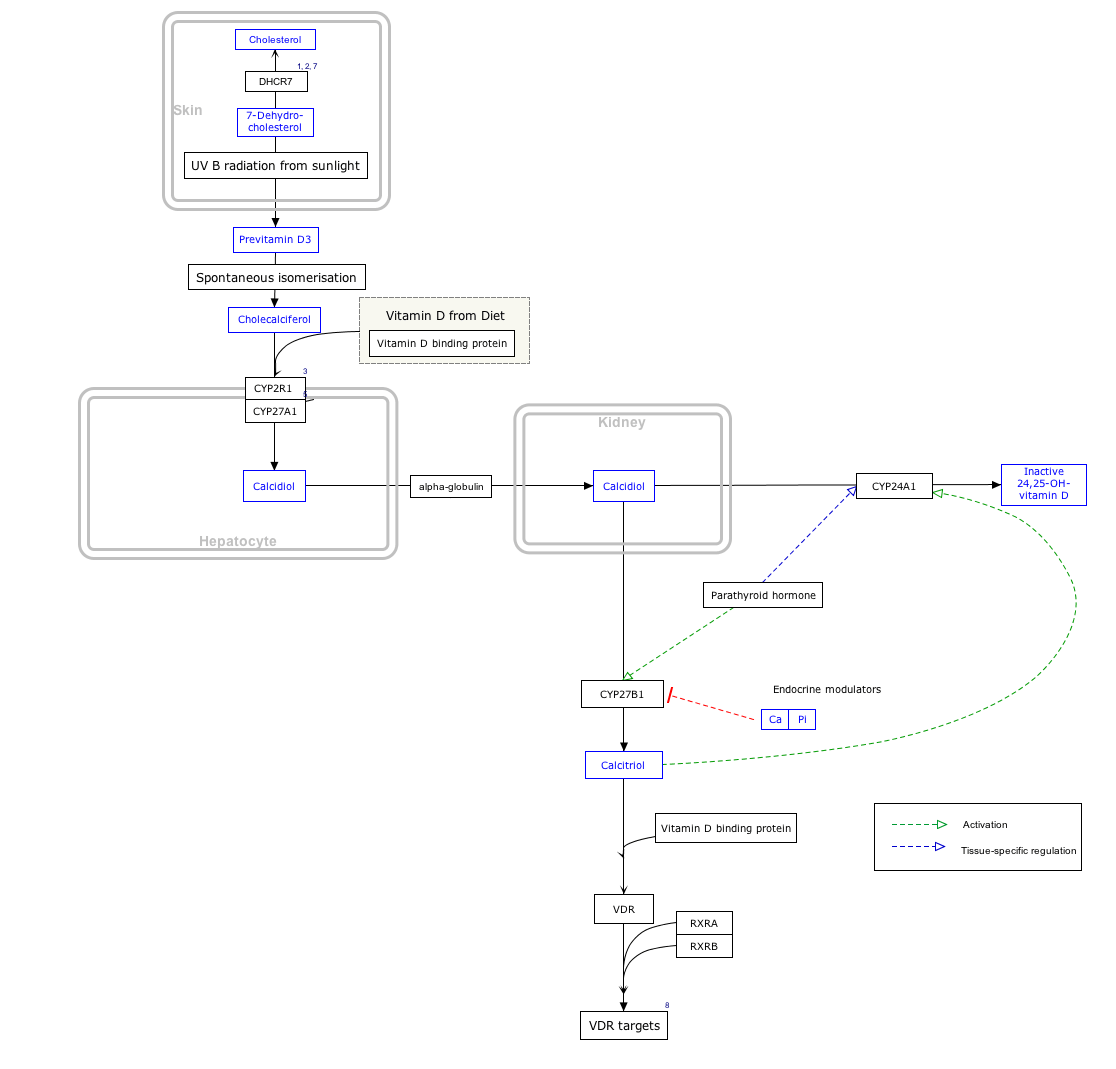

Interactive pathway map

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles. [§ 1]

Vitamin D Synthesis Pathway edit

- ↑ The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "VitaminDSynthesis_WP1531".

See also

- Hypervitaminosis D

- Hypovitaminosis D

- Vitamin D

- Health effects of Vitamin D

References

- ↑ "Nomenclature of Vitamin D. Recommendations 1981. IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN)" reproduced at the Queen Mary, University of London website. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- ↑ Holick, MF; Deluca, HF; Avioli, LV (1972). "Isolation and identification of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol from human plasma". Archives of Internal Medicine. 129 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1001/archinte.1972.00320010060005. PMID 4332591.

- ↑ Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1738–42 PMID 18541563

- ↑ Bender, David A.; Mayes, Peter A (2006). "Micronutrients: Vitamins & Minerals". In Victor W. Rodwell; Murray, Robert F.; Harper, Harold W.; Granner, Darryl K.; Mayes, Peter A. Harper's Illustrated Biochemistry. New York: Lange/McGraw-Hill. pp. 492–3. ISBN 0-07-146197-3. Retrieved December 10, 2008 through Google Book Search.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine (1997). "Vitamin D". Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press. p. 254. ISBN 0-309-06403-1.

- 1 2 "25-hydroxy vitamin D test: Medline Plus". Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- 1 2 Heaney, Robert P (Dec 2004). "Functional indices of vitamin D status and ramifications of vitamin D deficiency". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 80 (6): 1706S–9S. PMID 15585791.

- 1 2 3 4 American Society for Clinical Pathology, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Society for Clinical Pathology, retrieved August 1, 2013, which cites

- Sattar, N.; Welsh, P.; Panarelli, M.; Forouhi, N. G. (2012). "Increasing requests for vitamin D measurement: Costly, confusing, and without credibility". The Lancet. 379 (9811): 95–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61816-3. PMID 22243814.

- Bilinski, K. L.; Boyages, S. C. (2012). "The rising cost of vitamin D testing in Australia: Time to establish guidelines for testing". The Medical Journal of Australia. 197 (2): 90. doi:10.5694/mja12.10561. PMID 22794049.

- Lu, Chuanyi M. (May 2012). "Pathology consultation on vitamin D testing: Clinical indications for 25(OH) vitamin D measurement [Letter to the editor]". American Journal Clinical Pathology. American Society for Clinical Pathology (137): 831–832., which cites

- Arya, S. C.; Agarwal, N. (2012). "Pathology Consultation on Vitamin D Testing: Clinical Indications for 25(OH) Vitamin D Measurement". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 137 (5): 832. doi:10.1309/AJCP2GP0GHKQRCOE. PMID 22523224.

- Holick, M. F.; Binkley, N. C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H. A.; Gordon, C. M.; Hanley, D. A.; Heaney, R. P.; Murad, M. H.; Weaver, C. M. (2011). "Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention of Vitamin D Deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 96 (7): 1911–1930. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0385. PMID 21646368.

- ↑ Institute of Medicine (1997), p. 259

- ↑ Bender, David A. (2003). "Vitamin D". Nutritional biochemistry of the vitamins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80388-8. Retrieved December 10, 2008 through Google Book Search.

- ↑ Hollis BW (February 2005). "Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency: implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake recommendation for vitamin D". J Nutr. 135 (2): 317–22. PMID 15671234.

- ↑ Kimball; et al. (2004). "Safety of vitamin D3 in adults with multiple sclerosis". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 86 (3): 645–51. PMID 17823429.

- ↑ Maugh II, Thomas H. "Frank C. Garland dies at 60; epidemiologist helped show importance of vitamin D: Garland and his brother Cedric were the first to demonstrate that vitamin D deficiencies play a role in cancer and other diseases.", Los Angeles Times, August 31, 2010. Accessed September 4, 2010.

- ↑ Wactawski-Wende, J; Kotchen, JM, Women's Health Initiative Investigators (Mar 9, 2006). "Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer.". N Engl J Med. 354 (7): 684–96. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055222. PMID 16481636. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Too much vitamin D can be as unhealthy as too little" (Press release). University of Copenhagen. May 29, 2012. Retrieved 2015-05-27.

- ↑ Durup, D.; Jørgensen, H. L.; Christensen, J.; Schwarz, P.; Heegaard, A. M.; Lind, B. (May 9, 2012). "A Reverse J-Shaped Association of All-Cause Mortality with Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D in General Practice: The CopD Study". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. Endocrine Society. 97 (8): 2644–2652. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-1176. Retrieved 2015-05-27.