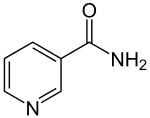

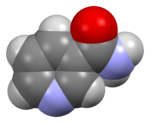

Nicotinamide

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Pyridine-3-carboxamide | |

| Other names

3-Pyridinecarboxamide Niacinamide Nicotinamide Nicotinic acid amide Vitamin PP | |

| Identifiers | |

| 98-92-0 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:17154 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL1140 |

| ChemSpider | 911 |

| DrugBank | DB02701 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.467 |

| EC Number | 202-713-4 |

| KEGG | D00036 |

| PubChem | 936 |

| UNII | 25X51I8RD4 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C6H6N2O | |

| Molar mass | 122.13 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White crystalline solid[1] |

| Density | 1.40 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 129.5 °C (265.1 °F; 402.6 K) |

| Boiling point | 334 °C (633 °F; 607 K) |

| log P | -.37 |

| Vapor pressure | 1.3*10−4mmHg |

| Pharmacology | |

| A11HA01 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | 69 °C; 156 °F; 342 K |

| 249 °C; 480 °F; 522 K | |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Nicotinamide, (/ˌnɪkəˈtɪnəmaɪd/) also known as niacinamide,[2][3] NAA, and nicotinic amide, is the amide of nicotinic acid (vitamin B3 / niacin).[2][3] Nicotinamide is a water-soluble vitamin and is part of the vitamin B group. Nicotinic acid, also known as niacin, is converted to nicotinamide in vivo, and, though the two are identical in their vitamin functions, nicotinamide does not have the same pharmacological and toxic effects of niacin, which occur incidental to niacin's conversion. Thus nicotinamide does not reduce cholesterol or cause flushing,[4] although nicotinamide may be toxic to the liver at doses exceeding 3 g/day for adults.[5] In cells, niacin is incorporated into nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP), although the pathways for nicotinic acid amide and nicotinic acid are very similar. NAD+ and NADP+ are coenzymes in a wide variety of enzymatic oxidation-reduction reactions.[6] Commercial production of niacin and niacinamide (several thousand tons annually) is by hydrolysis or aminolysis of 3-cyanopyridine (nicotinonitrile).[7]

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is one known cause of nicotinamide deficiency.

Use in medicine

Acne Vulgaris

Nicotinamide has anti-inflammatory actions. These may be of benefit to patients with inflammatory skin conditions.[8] These conditions include acne vulgaris, and the compound can suppress antigen-induced, lymphocytic transformation and inhibit 3',5'-cyclic-AMP phosphodiesterase. Nicotinamide has demonstrated the ability to block the inflammatory actions of iodides known to cause or exacerbate inflammatory acne.

NicAzel, Azerizin, and Nicomide are the names of oral acne medications that include nicotinamide as a predominant ingredient, based on this area of research. Nicotinamide is also used topically as a 4% or 5% gel or cream - as effective as topical 1% clindamycin (8-week double-blind trial) performed at the New York University College of Medicine.[9] Unlike topical Erythromycin or Clindamycin it does not lead to bacterial resistance to these antibiotics, when used to treat inflammatory acne. Nicotinamide acne treatment is also available as Nicotinamide pads and cream.

A 2013 double blinded clinical trial in the International Journal of Dermatology showed that topical 4% nicotinamide gel was as effective as 1% clindamycin gel in the treatment of moderate inflammatory acne vulgaris.[10] The study also showed that clindamycin worked better in people with non-oily (normal, dry) skin types, while nicotinamide worked better in people with oily skin types.

Nicotinamide increases the biosynthesis of ceramides in human keratinocytes in vitro and improves the epidermal permeability barrier in vivo.[11] The application of 2% topical nicotinamide for 2 and 4 weeks has been found to be effective in lowering the sebum excretion rate in study participants.[12] Nictotinamide has been shown to prevent Propionibacterium acnes-induced activation of toll-like receptor (TLR)-2, which ultimately results in the down-regulation of pro-inflammatory IL-8 production.[13] These are some of the possible mechanisms by which nicotinamide may help in acne vulgaris.

Skin cancer

A phase II double-blinded randomized controlled trial done at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Dermatology clinics in Sydney, Australia showed that oral nicotinamide may be effective at preventing actinic keratoses (AKs). Patients included in the study had significant skin cancer histories and were required to have at least 4 visible AKs at the time of entry into the study. Nicotinamide dosed at 500 mg twice daily showed a 35% reduction in AK count at 2 months and 4 months. Dosed at 500 mg once daily, a 15% reduction in AK count was seen at 2 months and 29% reduction at 4 months.[14]

A phase III double-blinded, randomized, and controlled trial investigating possible roles of nicotinamide in the prevention of non-melanoma skin cancer was performed by the same researchers who carried out the phase II trial referenced above. The trial enrolled 386 patients, who had at least two non-melanoma skin cancers in the last 5 years. The rates of new non-melanoma skin cancer diagnosed during the study period were 23% lower in the nicotinamide group (500 mg twice a day) compared to the placebo group. The study also showed that those in the nicotinamide group, AKs were reduced by 11% at 3 months, 20% at nine months, and 13% at 12 months compared to the placebo group. There was no added effect beyond the 12-month treatment period, suggesting that continuous dosing is necessary to see benefit. There were no differences between the groups with regard to adverse effects.[15]

Anxiety

Studies show that nicotinamide has anxiolytic (anti-anxiety) properties. It may work in a way similar to benzodiazepines.[16][17][18][19]

Cancer

Nicotinamide may aid chemotherapy-and radiation therapy by acting as a sensitizing agent/cancer-growth-promoter resulting in enhanced blood flow to tumors and thus increased oxygen supply to tumors, thereby reducing tumor hypoxia. Niacinamide also inhibits poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARP-1), enzymes involved in the rejoining of DNA strand breaks induced by radiation or chemotherapy.[20] PARP-1 appears to be an important target for triple negative breast cancers because the cells are sensitive to inhibition of PARP-1.[21] Niacinamide is also used by some patients in combination with "intravenous vitamin C" treatment for cancer.[22] Niacinamide has also been reported as preventing suppression of the immune system caused by UVA and UVB radiation (so it could potentially be added to sunscreen).[23]

Bullous Pemphigoid

In an open label randomized trial with twenty patients having bullous pemphigoid (BP), tetracycline combined with oral nictotinamide was shown to be as effective as prednisone in treating BP.[24] There are several case reports which support the efficacy of this therapy.[25] It is considered to be a steroid sparing regimen. Recommended dosing is tetracycline 500 mg four times daily or doxycycline100mg twice daily or minocycline 100 mg twice daily, combined with nicotinamide 500 mg four times daily.[26]

Apoptosis

Nicotinamide can prevent apoptosis (programmed cell death) in cells exposed to agents that induce oxidative stress. Thus nicotinamide prevents apoptosis in human cortical neuronal cells when oxidative stress is induced by tertiary butylhydroperoxide,[27] and in Jurkat (human T-cell lymphoma cells) when oxidative stress is induced by sodium deoxycholate.[28]

Other

Nicotinamide reportedly increases the endurance of mice.[29]

Nicotinamide is also reported to be an effective skin whitener in topical application.[30][31]

Food sources

Nicotinamide occurs in trace amounts mainly in meat, fish, nuts, and mushrooms, as well as to a lesser extent in some vegetables.[32]

Some countries require fortification with nicotinamide of some foods. For example, the UK requires fortification of flour and bread with nicotinamide.

Nicotinamide is an ingredient in some energy shots such as 5-hour Energy.[33][34]

Toxicity

Nicotinamide lacks the vasodilator, gastrointestinal, hepatic, and hypolipidemic actions of nicotinic acid. As such, nicotinamide has not been shown to produce the flushing, itching, and burning sensations of the skin as is commonly seen when large doses of nicotinic acid are administered orally. High-dose nicotinamide should still, however, be considered as a drug with toxic potential at adult doses in excess of 3 g/day and unsupervised use should be discouraged.[5] Overall, however, it rarely causes side effects, and is considered generally safe as a food additive, and as a component in cosmetics and medication.[35]

Compendial status

See also

Notes and references

- 1 2 Record in the GESTIS Substance Database of the IFA

- 1 2 Rolfe HM (2014). "A review of nicotinamide: treatment of skin diseases and potential side effects". Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 13 (4): 324–8. doi:10.1111/jocd.12119. PMID 25399625.

Nicotinamide, also known as niacinamide, is the amide form of vitamin B3.

- 1 2 MacKay D, Hathcock J, Guarneri E (2012). "Niacin: chemical forms, bioavailability, and health effects" (PDF). Nutrition Reviews. 70 (6): 357–66. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00479.x. PMID 22646128. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

The forms of niacin available in the marketplace include unbound niacin, or free nicotinic acid (NA); extended-release NA, a form of NA that is released gradually over a period of time; inositol hexanicotinate, six molecules of NA covalently bonded to one molecule of inositol; and nicotinamide, or niacinamide, the amide form of NA, which is readily bioavailable.

- ↑ Jacenollo, P. (1992). Niacin versus niacinamide

- 1 2 Knip M, Douek IF, Moore WP, et al. (2000). "Safety of high-dose nicotinamide: a review". Diabetologia. 43 (11): 1337–45. doi:10.1007/s001250051536. PMID 11126400.

- ↑ Belenky P; Bogan KL; Brenner C (2007). "NAD+ metabolism in health and disease" (PDF). Trends Biochem. Sci. 32 (1): 12–9. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.006. PMID 17161604. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ↑ Manfred Eggersdorfer; et al. (2000). "Vitamins". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a27_443.

- ↑ Niren NM (2006). "Pharmacologic doses of nicotinamide in the treatment of inflammatory skin conditions: a review". Cutis. 77 (1 Suppl): 11–6. PMID 16871774.

- ↑ Shalita AR, Smith JG, Parish LC, Sofman MS, Chalker DK (June 1995). "Topical nicotinamide compared with clindamycin gel in the treatment of inflammatory acne vulgaris". International Journal of Dermatology. 34 (6): 434–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb04449.x. PMID 7657446.

- ↑ Khodaeiani, Effat; Fouladi, Rohollah Fadaei; Amirnia, Mehdi; Saeidi, Majid; Karimi, Elham Razagh (2013-08-01). "Topical 4% nicotinamide vs. 1% clindamycin in moderate inflammatory acne vulgaris". International Journal of Dermatology. 52 (8): 999–1004. doi:10.1111/ijd.12002. ISSN 1365-4632.

- ↑ Tanno, O.; Ota, Y.; Kitamura, N.; Katsube, T.; Inoue, S. (2000-09-01). "Nicotinamide increases biosynthesis of ceramides as well as other stratum corneum lipids to improve the epidermal permeability barrier". British Journal of Dermatology. 143 (3): 524–531. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2000.03705.x. ISSN 1365-2133.

- ↑ Draelos, Zoe Diana; Matsubara, Akira; Smiles, Kenneth (2006-01-01). "The effect of 2% niacinamide on facial sebum production". Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 8 (2): 96–101. doi:10.1080/14764170600717704. ISSN 1476-4172.

- ↑ Kim, Jenny; Ochoa, Maria-Teresa; Krutzik, Stephan R.; Takeuchi, Osamu; Uematsu, Satoshi; Legaspi, Annaliza J.; Brightbill, Hans D.; Holland, Diana; Cunliffe, William J. (2002-08-01). "Activation of Toll-Like Receptor 2 in Acne Triggers Inflammatory Cytokine Responses". The Journal of Immunology. 169 (3): 1535–1541. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1535. ISSN 0022-1767. PMID 12133981.

- ↑ Surjana, Devita; Halliday, Gary M.; Martin, Andrew J.; Moloney, Fergal J.; Damian, Diona L. (2012-05-01). "Oral Nicotinamide Reduces Actinic Keratoses in Phase II Double-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trials". Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 132 (5): 1497–1500. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.459. ISSN 0022-202X.

- ↑ Andrew James Martin; Andrew Chen; Bonita Choy; Pablo Fernandez Penas; Gary Halliday; Robyn Dalziell; Catriona McKenzie; Richard A Scolyer; Haryana M. Dhillon; Janette L. Vardy; Gaya St George; Nira Chinniah; Diona Damian (2015). "Oral nicotinamide to reduce actinic cancer: A phase 3 double-blind randomized controlled trial.". American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Chicago, 30 May 2015. J Clin Oncol 33, 2015 (suppl; abstr 9000).

- ↑ Tallman JF, Paul SM, Skolnick P, Gallager DW (1980). "Receptors for the age of anxiety: pharmacology of the benzodiazepines". Science. 207 (4428): 274–81. doi:10.1126/science.6101294. PMID 6101294.

- ↑ Paul, SM; Marangos, PJ; Skolnick, P; Goodwin, FK (1982). "Biological substrates of anxiety: benzodiazepine receptors and endogenous ligands.". L'Encephale. 8 (2): 131–44. PMID 6125374.

- ↑ Akhundov, RA; Sultanov, AA; Gadzhily, RA; Sadykhov, RV (May 1993). "[Psychoregulating role of nicotinamide].". Biulleten' eksperimental'noi biologii i meditsiny. 115 (5): 487–91. PMID 7913840.

- ↑ Möhler H, Polc P, Cumin R, Pieri L, Kettler R (April 1979). "Nicotinamide is a brain constituent with benzodiazepine-like actions". Nature. 278: 563–565. doi:10.1038/278563a0. PMID 155222.

- ↑ Definition of niacinamide, National Cancer Institute

- ↑ Efficacy of BSI-201, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) inhibitor, in combination with gemcitabine/carboplatin (G/C) in patients with metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC): Results of a randomized phase II trial.

- ↑ Intravenously administered vitamin C as cancer therapy: three cases

- ↑ Damian DL, Patterson CR, Stapelberg M, Park J, Barnetson RS, Halliday GM (February 2008). "UV radiation-induced immunosuppression is greater in men and prevented by topical nicotinamide". J. Invest. Dermatol. 128 (2): 447–54. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5701058. PMID 17882270.

- ↑ Fivenson, D. P. "Nicotinamide and tetracycline therapy of bullous pemphigoid". Archives of Dermatology. 130 (6): 753–758. doi:10.1001/archderm.130.6.753.

- ↑ Chen, Andrew C; Damian, Diona L (2014-08-01). "Nicotinamide and the skin". Australasian Journal of Dermatology. 55 (3): 169–175. doi:10.1111/ajd.12163. ISSN 1440-0960.

- ↑ "Management and prognosis of bullous pemphigoid". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2015-10-20.

- ↑ Bhansali SG, Brazeau DA, Sonee M, Mukherjee SK. (2006). Nicotinamide prevents apoptosis in human cortical neuronal cells. Toxicol Mech Methods 16(4):173-180. doi: 10.1080/15376520500194726. PMID 20021043

- ↑ Crowley, CL; Payne, CM; Bernstein, H; Bernstein, C; Roe, D (2000). "The NAD+ precursors, nicotinic acid and nicotinamide protect cells against apoptosis induced by a multiple stress inducer, deoxycholate". Cell Death Differ. 7 (3): 314–326. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4400658. PMID 10745276.

- ↑ Fukuwatari T, Shibata K, Ishihara K, Fushiki T, Sugimoto E (April 2001). "Elevation of blood NAD level after moderate exercise in young women and mice". J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 47 (2): 177–9. doi:10.3177/jnsv.47.177. PMID 11508711.

- ↑ Hakozaki T, Minwalla L, Zhuang J, et al. (July 2002). "The effect of niacinamide on reducing cutaneous pigmentation and suppression of melanosome transfer". Br. J. Dermatol. 147 (1): 20–31. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04834.x. PMID 12100180.

- ↑ Navarrete-Solís J, Castanedo-Cázares JP, Torres-Álvarez B, et al. (July 2011). "A Double-Blind, Randomized Clinical Trial of Niacinamide 4% versus Hydroquinone 4% in the Treatment of Melasma". Dermatol Res Pract. 2011 (379173): 1–5. doi:10.1155/2011/379173. PMC 3142702

. PMID 21822427.

. PMID 21822427. - ↑ Rolfe, Heidi M (2014-12-01). "A review of nicotinamide: treatment of skin diseases and potential side effects". Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 13 (4): 324–328. doi:10.1111/jocd.12119. ISSN 1473-2165. PMID 25399625.

- ↑ "5-hour Energy Shot Ingredients".

- ↑ http://theomegareview.com/home/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/5-Hour-Energy-Nutrition-Label.jpg

- ↑ Cosmetic Ingredient Review Expert Panel (2005). "Final report of the safety assessment of niacinamide and niacin". Int. J. Toxicol. 24 Suppl 5: 1–31. doi:10.1080/10915810500434183. PMID 16596767.

- ↑ British Pharmacopoeia Commission Secretariat (2009). "Index, BP 2009" (PDF). Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ↑ "Japanese Pharmacopoeia, Fifteenth Edition" (PDF). 2006. Retrieved 4 February 2010.