Theobromine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | C03BD01 (WHO) R03DA07 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic demethylation and oxidation |

| Biological half-life | 7.1±0.7 hours |

| Excretion | Renal (10% unchanged, rest as metabolites) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms |

xantheose diurobromine 3,7-dimethylxanthine |

| CAS Number |

83-67-0 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5429 |

| DrugBank |

DB01412 |

| ChemSpider |

5236 |

| UNII |

OBD445WZ5P |

| KEGG |

C07480 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:28946 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1114 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.359 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C7H8N4O2 |

| Molar mass | 180.164 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

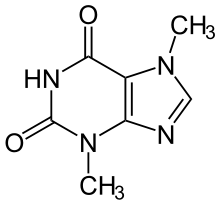

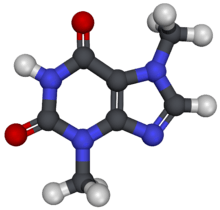

Theobromine, formerly known as xantheose,[1] is a bitter alkaloid of the cacao plant, with the chemical formula C7H8N4O2.[1] It is found in chocolate, as well as in a number of other foods, including the leaves of the tea plant, and the kola (or cola) nut. It is classified as a xanthine alkaloid,[2] which also include the similar compounds theophylline and caffeine.[1] The compounds differ in their methylation.

Despite its name, the compound contains no bromine—theobromine is derived from Theobroma, the name of the genus of the cacao tree, (which itself is made up of the Greek roots theo ("god") and broma ("food"), meaning "food of the gods"[3] with the suffix -ine given to alkaloids and other basic nitrogen-containing compounds.[4]

Theobromine is a slightly water-soluble (330 mg/L[5]), crystalline, bitter powder. Theobromine is white or colourless, but commercial samples can be yellowish.[6] It has an effect similar to, but lesser than, that of caffeine in the human nervous system, making it a lesser homologue. Theobromine is an isomer of theophylline, as well as paraxanthine. Theobromine is categorized as a dimethyl xanthine.[7]

Theobromine was first discovered in 1841[8] in cacao beans by Russian chemist Alexander Voskresensky.[9] Synthesis of theobromine from xanthine was first reported in 1882 by Hermann Emil Fischer.[10][11]

Sources

Theobromine is the primary alkaloid found in cocoa and chocolate. Cocoa powder can vary in the amount of theobromine, from 2%[12] theobromine, up to higher levels around 10%. There are usually higher concentrations in dark than in milk chocolate.[13] Theobromine can also be found in small amounts in the kola nut (1.0–2.5%), the guarana berry, Ilex paraguariensis (yerba mate), and the tea plant.[14] 28 grams (1 oz) of milk chocolate contains approximately 60 milligrams (1 grain) of theobromine,[15] while the same amount of dark chocolate contains about 200 milligrams (3 grains).[16] Cocoa beans naturally contain approximately 1% theobromine.[17]

The plant species with the largest amounts of theobromine are:[18]

- Theobroma cacao

- Theobroma bicolor

- Ilex paraguariensis

- Ilex guayusa

- Camellia sinensis

- Cola acuminata

- Theobroma angustifolium

- Guarana

- Coffea arabica

The mean theobromine concentrations in cocoa and carob products are:[19]

| Item | Mean theobromine content ratio (10−3) |

|---|---|

| Cocoa | 20.3 |

| Cocoa cereals | 0.695 |

| Chocolate bakery products | 1.47 |

| Chocolate toppings | 1.95 |

| Cocoa beverages | 2.66 |

| Chocolate ice creams | 0.621 |

| Chocolate milks | 0.226 |

| Carob products | 0.000–0.504 |

Biosynthesis

Theobromine is a purine alkaloid derived from xanthosine, a nucleoside. Cleavage of the ribose and N-methylation yields 7-methylxanthosine. 7-Methylxanthosine in turn is the precursor to theobromine, which in turn is the precursor to caffeine.[20]

Therapeutic uses

Theobromine is a vasodilator (a blood vessel widener), a diuretic (urination aid), and heart stimulant.[1] It is not currently used as a medicinal drug.[21]

Theobromine increases urine production. Because of this diuretic effect, and its ability to dilate blood vessels, theobromine has been used to treat high blood pressure.[22] The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition notes that historic use of theobromine as a treatment for other circulatory problems including arteriosclerosis, certain vascular diseases, angina pectoris, and hypertension should be considered in future studies.[23]

Following its discovery in the late 19th century, theobromine was put to use by 1916, when it was recommended by the publication Principles of Medical Treatment as a treatment for edema (excessive liquid in parts of the body), syphilitic angina attacks, and degenerative angina.[24]

In the human body, theobromine levels are halved between 6–10 hours after consumption.[22]

Theobromine has also been used in birth defect experiments involving mice and rabbits. A decreased fetal weight was noted in rabbits following forced feeding, but not after other administration of theobromine. Birth defects were not seen in rats.[25] Possible future uses of theobromine in such fields as cancer prevention have been patented.[26]

Theobromine has also been shown to improve the microhardness of tooth enamel which could potentiality increase resistance to tooth decay.[21][27]

Pharmacology

Even without dietary intake, theobromine may occur in the body as it is a product of the human metabolism of caffeine, which is metabolised in the liver into 12% theobromine, 4% theophylline, and 84% paraxanthine.[28]

In the liver, theobromine is metabolized into xanthine and subsequently into methyluric acid.[29] Important enzymes include CYP1A2 and CYP2E1.[30]

Like other methylated xanthine derivatives, theobromine is both a:

- competitive nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor,[31] which raises intracellular cAMP, activates PKA, inhibits TNF-alpha[32][33] and leukotriene[34] synthesis, and reduces inflammation and innate immunity[34] and

- nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist.[35]

As a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, theobromine prevents the phosphodiesterase enzymes from converting the active cAMP to an inactive form.[36] cAMP works as a second messenger in many hormone- and neurotransmitter-controlled metabolic systems, such as the breakdown of glycogen. When the inactivation of cAMP is inhibited by a compound such as theobromine, the effects of the neurotransmitter or hormone that stimulated the production of cAMP are much longer-lived. In general, the net result is a stimulatory effect.[37]

Effects

Humans

The amount of theobromine found in chocolate is small enough that chocolate can, in general, be safely consumed by humans. Theobromine poisoning may result from the chronic or acute consumption of large quantities, especially in the elderly.[38]

Theobromine and caffeine are similar in that they are related alkaloids. Theobromine is weaker in both its inhibition of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases and its antagonism of adenosine receptors.[39] Therefore, theobromine has a lesser impact on the human central nervous system than caffeine. Theobromine stimulates the heart to a greater degree.[40] While theobromine is not as addictive, it has been cited as possibly causing addiction to chocolate.[41] Theobromine has also been identified as one of the compounds contributing to chocolate's reputed role as an aphrodisiac.[42]

As it is a myocardial stimulant as well as a vasodilator, it increases heartbeat, and also dilates blood vessels, causing a reduced blood pressure.[43] A 2005 paper published suggested that the decrease in blood pressure may be caused by flavanols.[23] Its draining effect allows it to be used to treat cardiac failure, which leads to and is exacerbated by an excessive accumulation of fluid in the body.[43]

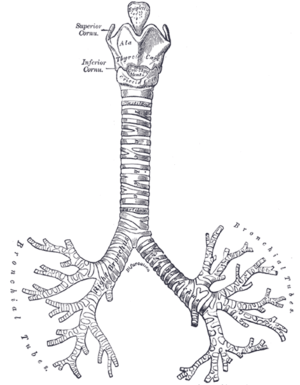

A 2004 study published by Imperial College London concluded that theobromine has an antitussive (cough-reducing) effect superior to codeine by suppressing vagus nerve activity.[44] In the study, 1,000 milligrams (0.035 oz) theobromine (equivalent to ~71 grams (2.5 oz) dark chocolate) significantly increased the threshold of capsaicin concentration required to induce coughs when compared with a placebo.[44] A drug, called BC1036, is being developed by the private UK company infirst Healthcare and it uses theobromine to treat persistent cough.[45] Theobromine is helpful in treating asthma, since it relaxes the smooth muscles, including the ones found in the bronchi.[46]

A study conducted in Utah between 1983 and 1986, and published in 1993, showed a possible association between theobromine and an increased risk of prostate cancer in older men.[47] This association was not found to be linear for aggressive tumors.[47] The association may be spurious, but is plausible.[47] Prenatal and infant exposure to theobromine appeared possibly associated with hypospadias and testicular cancer in one population study.[48]

As with caffeine, theobromine can cause sleeplessness, tremors, restlessness, anxiety, as well as contribute to increased production of urine. Additional side effects include loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and withdrawal headaches.

Animals

Animals that metabolize theobromine (found in chocolate) more slowly, such as dogs , can succumb to theobromine poisoning from as little as 50 grams (1.8 oz) of milk chocolate for a smaller dog and 400 grams (14 oz), or around nine 44-gram (1.55 oz) small milk chocolate Hershey bars, for an average-sized dog. It should be observed the concentration of theobromine in dark chocolates (approximately 10 g/kg (0.16 oz/lb)) is up to 10 times that of milk chocolate (1 to 5 g/kg (0.016 to 0.080 oz/lb)) - meaning dark chocolate is far more toxic to dogs per unit weight or volume than milk chocolate.

The same risk is reported for cats as well,[49] although cats are less likely to ingest sweet food, with most cats having no sweet taste receptors.[50] Complications include digestive issues, dehydration, excitability, and a slow heart rate. Later stages of theobromine poisoning include epileptic-like seizures and death. If caught early on, theobromine poisoning is treatable.[51] Although not usual, the effects of theobromine poisoning, as stated, can become fatal.

In 2014, four American black bears were found dead at a bait site in New Hampshire. A necropsy and toxicology reports performed at the University of New Hampshire in 2015 confirmed they died of heart failure caused by theobromine after they consumed 41 kilograms (90 lb) of chocolate and doughnuts placed at the site as bait. A similar incident killed a black bear cub in Michigan in 2011.[52]

The toxicity for birds is not known, but it is typically assumed that it is toxic to birds.[53]

Gene mutation in mammalian cells

Theobromine is known to induce gene mutations in lower eukaryotes and bacteria. In 1991 and 1997, research by the International Agency for Research on Cancer had shown that genetic mutations occurred in higher eukaryotic cells, specifically cultured mammalian cells. Despite this, theobromine is still listed as safe for human consumption due to inadequate evidence of carcinogenicity.[54]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 William Marias Malisoff (1943). Dictionary of Bio-Chemistry and Related Subjects. Philosophical Library. pp. 311, 530, 573. ASIN B0006AQ0NU.

- ↑ Baer, Donald M.; Elsie M. Pinkston (1997). Environment and Behavior. Westview Press. p. 200.

- ↑ Bennett, Alan Weinberg; Bonnie K. Bealer (2002). The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug. Routledge, New York. ISBN 0-415-92723-4. (note: the book incorrectly states that the name "theobroma" is derived from Latin)

- ↑ "-ine". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2004. ISBN 0-395-71146-0.

- ↑ Theobromine in the ChemIDplus database

- ↑ "theobromine". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2007-02-22. For convenience, the direct source of the three definitions used has been cited.

- ↑ "Theobromine". On-Line Medical Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Plant intoxicants: a classic text on ... - Google Books. Books.google.ru. Retrieved on 2009-11-08.

- ↑ Woskresensky A (1842). "Über das Theobromin". Liebigs Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 41: 125–127. doi:10.1002/jlac.18420410117.

- ↑ Thomas Edward Thorpe (1902). Essays in Historical Chemistry. The MacMillan Company.

- ↑ Fischer Emil (1882). "Umwandlung des Xanthin in Theobromin und Caffein". Berichte der deutsche chemischen Gesellschaft. 15 (1): 453–456. doi:10.1002/cber.18820150194. See also: Fischer, E. (1882). "Über Caffein, Theobromin, Xanthin und Guanin". Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 215 (3): 253–320. doi:10.1002/jlac.18822150302.

- ↑ "Theobromine content of Hershey's confectionery products". The Hershey Company. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ↑ "AmerMed cocoa extract with 10% theobromine". AmerMed. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- ↑ Ghillean Prance; Mark Nesbitt (2004). The Cultural History of Plants. New York: Routledge. pp. 137, 175, 178–180. ISBN 0-415-92746-3.

- ↑ "USDA Nutrient database, entries for milk chocolate". Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ↑ "USDA Nutrient database, entries for dark chocolate". Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- ↑ Kuribara H, Tadokoro S (April 1992). "Behavioral effects of cocoa and its main active compound theobromine: evaluation by ambulatory activity and discrete avoidance in mice". Arukōru Kenkyū to Yakubutsu Izon. 27 (2): 168–79. PMID 1586288.

- ↑ "Activities of a Specific Chemical Query - Theobromine". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ Craig, Winston J.; Nguyen, Thuy T. (1984). "Caffeine and theobromine levels in cocoa and carob products". Journal of Food Science. 49 (1): 302–303. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1984.tb13737.x. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

Mean theobromine and caffeine levels respectively, were 0.695 mg/g and 0.071 mg/g in cocoa cereals; 1.47 mg/g and 0.152 mg/g in chocolate bakery products; 1.95 mg/g and 0.138 mg/g in chocolate toppings; 2.66 mg/g and 0.208 mg/g in cocoa beverages; 0.621 mg/g and 0.032 mg/g in chocolate ice creams; 0.226 mg/g and 0.011 mg/g in chocolate milks; 74.8 mg/serving and 6.5 mg/serving in chocolate puddings.... Theobromine and caffeine levels in carob products ranged from 0-0.504 mg/g and 0-0.067 mg/g, respectively.

- ↑ Ashihara Hiroshi; Yokota Takao; Crozier Alan (2013). "Biosynthesis and catabolism of purine alkaloids". Advances in Botanical Research. 68: 111–138. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-408061-4.00004-3.

- 1 2 Smit, HJ (2011). "Theobromine and the pharmacology of cocoa.". Handbook of experimental pharmacology (200): 218. PMID 20859797.

- 1 2 Anne Marie Helmenstine. "Theobromine Chemistry". About.com Education.

- 1 2 Kelly, Caleb J (August 2005). "Effects of theobromine should be considered in future studies". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 82 (2): 486–7; author reply 487–8. PMID 16087999.

- ↑ George Cheever Shattuck (1916). Principles of medical treatment. W.M. Leonard. pp. 15, 39, 41.

- ↑ Rambali B; Andel I van; Schenk E; Wolterink G; Werken G van de; Stevenson H; Vleeming W (2002). "[The contribution of cocoa additive to cigarette smoking addiction]" (PDF). RIVM (report 650270002/2002).- The National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (Netherlands)

- ↑ US 6693104, "Theobromine with an anti-carcinogenic activity", issued 2004-02-17

- ↑ Kargul B, Özcan M, Peker S, Nakamoto T, Simmons WB, Falster AU (2012). "Evaluation of human enamel surfaces treated with theobromine: a pilot study". Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry. 10 (3): 275–82. PMID 23094271.

- ↑ "Caffeine". The Pharmacogenetics and Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ↑ Herbert H. Cornish; A. A. Christman (1957). "A Study of the Metabolism of Theobromine, Theophylline, and Caffeine in Man". Ann Arbor, Michigan: Department of Biological Chemistry, Medical School, University of Michigan.

- ↑ Gates S, Miners JO (March 1999). "Cytochrome P450 isoform selectivity in human hepatic theobromine metabolism". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 47 (3): 299–305. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00890.x. PMC 2014222

. PMID 10215755.

. PMID 10215755. - ↑ Essayan DM. (2001). "Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 108 (5): 671–80. doi:10.1067/mai.2001.119555. PMID 11692087.

- ↑ Deree J, Martins JO, Melbostad H, Loomis WH, Coimbra R (2008). "Insights into the regulation of TNF-alpha production in human mononuclear cells: the effects of non-specific phosphodiesterase inhibition". Clinics (São Paulo). 63 (3): 321–8. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322008000300006. PMC 2664230

. PMID 18568240.

. PMID 18568240. - ↑ Marques LJ, Zheng L, Poulakis N, Guzman J, Costabel U (February 1999). "Pentoxifylline inhibits TNF-alpha production from human alveolar macrophages". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159 (2): 508–11. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9804085. PMID 9927365.

- 1 2 Peters-Golden M, Canetti C, Mancuso P, Coffey MJ (2005). "Leukotrienes: underappreciated mediators of innate immune responses". J Immunol. 174 (2): 589–94. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.589. PMID 15634873.

- ↑ Daly JW, Jacobson KA, Ukena D (1987). "Adenosine receptors: development of selective agonists and antagonists". Prog Clin Biol Res. 230 (1): 41–63. PMID 3588607.

- ↑

- "Phosphodiesterase". On-Line Medical Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

"Inhibitor". On-Line Medical Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- "Phosphodiesterase". On-Line Medical Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ↑ David L. Nelson; Michael M. Cox (2005). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 435–439. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- ↑ See: THEOBROMINE, CASRN: 83-67-0 in the Hazardous Substances Data Bank

- ↑ Joel Hardman; Lee Limbird, eds. (2001). Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics, 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 745. ISBN 0-07-135469-7.

- ↑ Howell, L.L., Coffin, V.L., Spealman, R.D. Behavorial and physiological effects of xanthines in nonhuman primates (1997) Psychopharmacology, 129 (1), pp. 1–14.

- ↑ William Gervase Clarence-Smith (2000). Cocoa and Chocolate, 1765–1914. London: Routledge. pp. 10, 31. ISBN 0-415-21576-5.

- ↑ Kenneth Maxwell (1996). A Sexual Odyssey: From Forbidden Fruit to Cybersex. New York: Plenum. pp. 38–40. ISBN 0-306-45405-X.

- 1 2 US 20050089584, "Methods and compositions for oral delivery of Areca and mate' or theobromine", issued 2005-04-28

- 1 2 Usmani, Omar S.; Belvisi, Maria G.; Patel, Hema J.; Crispino, Natascia; Birrell Mark A.; Korbonits, Márta; Korbonits, Dezső; Barnes, Peter J. (November 17, 2004). "Theobromine inhibits sensory nerve activation and cough". FASEB Journal. 19 (2): 231–3. doi:10.1096/fj.04-1990fje. PMID 15548587. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

The present study demonstrates that theobromine, a methylxanthine derivative present in cocoa, effectively inhibits citric acid-induced cough in guinea-pigs in vivo. Furthermore, in a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study in man, theobromine suppresses capsaicin-induced cough with no adverse effects. We also demonstrate that theobromine directly inhibits capsaicin-induced sensory nerve depolarization of guinea-pig and human vagus nerve suggestive of an inhibitory effect on afferent nerve activation.

- ↑ "'Chocolate cough remedy' in sight". BBC News. 2010-12-21. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ↑ Irwin J. Polk (1997). All about Asthma: Stop Suffering and Start Living. New York: Insight Books. p. 100. ISBN 0-306-45569-2.

- 1 2 3 Slattery, Martha L.; West, Dee W. (1993). "Smoking, alcohol, coffee, tea, caffeine, and theobromine: risk of prostate cancer in Utah (United States)". Cancer Causes Control. 4 (6): 559–63. doi:10.1007/BF00052432. PMID 8280834.

Compared with men with very low levels of theobromine intake, older men consuming 11 to 20 and over 20 mg of theobromine per day were at increased risk of prostate cancer (odds ratio-[OR] for all tumors = 2.06, 95 percent confidence interval [CI] = 1.33-3.20, and OR = 1.47, CI = 0.99-2.19, respectively; OR for aggressive tumors -- 1.90, CI = 0.90-3.97, and OR -- 1.74, CI -- 0.91-3.32, respectively)

- ↑ Giannandrea F (February 2009). "Correlation analysis of cocoa consumption data with worldwide incidence rates of testicular cancer and hypospadias". Int J Environ Res Public Health. 6 (2): 568–78. doi:10.3390/ijerph6020578. PMC 2672359

. PMID 19440400.

. PMID 19440400. - ↑ http://aspcapro.org/sites/pro/files/m-toxbrief_0201_0.pdf

- ↑ "The Poisonous Chemistry of Chocolate". WIRED. 14 February 2013.

- ↑ "HEALTH WATCH: How to Avoid a Canine Chocolate Catastrophe!". The News Letter. Belfast, Northern Ireland. 2005-03-01.

- ↑ 4 bears die of chocolate overdoses; expert proposes ban. Retrieved 2015-01-22.

- ↑ B. Harvey, Toxicoses in Birds.

- ↑ International Agency for Research on Cancer (November 17, 1991). "Volume 51: Coffee, Tea, Mate, Methylxanthines and Methylglyoxal - Theobromine" (PDF). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. WHO. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

Further reading

- Bender, David A.; Arnold E. Bender (1995). A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860961-2.

- from the Hazardous Substances Data Bank