Asparaginase

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Elspar |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682046 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | IM or IV |

| ATC code | L01XX02 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Biological half-life | 39-49 hours (IM), 8-30 hours (IV) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

9015-68-3 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 7347 |

| DrugBank |

DB00023 |

| ChemSpider | none |

| UNII |

G4FQ3CKY5R |

| KEGG |

D02997 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C1377H2208N382O442S17 |

| Molar mass | 31731.9 g/mol |

| (verify) | |

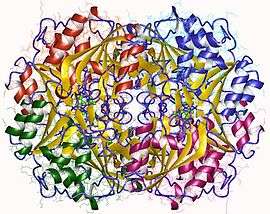

Asparaginase (EC 3.5.1.1, USAN) or Colaspase (BAN) is an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of asparagine to aspartic acid. Asparaginases are enzymes expressed and produced by microorganisms.[1]

They are used in food manufacture, and in medicine to treat some cancers. These [medical] enzymes are on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines[2]

Uses

Asparaginases can be used for different industrial and pharmaceutical purposes.

Medical

E. coli strains are the main source of medical asparaginase.[3] Branded formulations (with different chemical and pharmacological properties) available in 1998 include Asparaginase Medac, Ciderolase, and Oncaspar.[3]:5 (Crasnitin has been discontinued.) Spectrila® is a new recombinant E. coli asparaginase. [4]

Asparaginase produced by Erwinia chrysanthemi instead is known as crisantaspase (BAN), and is available in the United Kingdom under the trade name Erwinase.[5]

One of the E. coli asparaginases marketed under the brand name Elspar for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)[5] is also used in some mast cell tumor protocols.[6]

Unlike most of other chemotherapy agents, asparaginase can be given as an intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intravenous injection without fear of tissue irritation.

Food manufacturing

The most common use of asparaginases is as a processing aid in the manufacture of food. Marketed under the brand names Acrylaway and PreventASe, asparaginases are used as a food processing aid to reduce the formation of acrylamide, a suspected carcinogen, in starchy food products such as snacks and biscuits.[7]

Side effects

The main side effect is an allergic or hypersensitivity reaction; anaphylaxis is a possibility.[5] Additionally, it can also be associated with a coagulopathy as it decreases protein synthesis, including synthesis of coagulation factors (e.g. progressive isolated decrease of fibrinogen) and anticoagulant factor (generally antithrombin III; sometimes protein C & S as well), leading to bleeding or thrombotic events such as stroke.[3] Bone marrow suppression is common but only mild to moderate, rarely reaches clinical significance and therapeutic consequences are rarely required.[8]

Other common side effects include pancreatitis.

Mechanism of action

As a food processing aid

Acrylamide is often formed in the cooking of starchy foods. During heating the amino acid asparagine, naturally present in starchy foods, undergoes a process called the Maillard reaction, which is responsible for giving baked or fried foods their brown color, crust, and toasted flavor. Suspected carcinogens such as acrylamide and some heterocyclic amines are also generated in the Maillard reaction. By adding asparaginase before baking or frying the food, asparagine is converted into another common amino acid, aspartic acid, and ammonium. As a result, asparagine cannot take part in the Maillard reaction, and therefore the formation of acrylamide is significantly reduced. Complete acrylamide removal is probably not possible due to other, minor asparagine-independent formation pathways.[7]

As a food processing aid, asparaginases can effectively reduce the level of acrylamide up to 90% in a range of starchy foods without changing the taste and appearance of the end product.[9]

As a drug

The rationale behind asparaginase is that it takes advantage of the fact that acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells and some other suspected tumor cells are unable to synthesize the non-essential amino acid asparagine, whereas normal cells are able to make their own asparagine; thus leukemic cells require high amount of asparagine.[10] These leukemic cells depend on circulating asparagine. Asparaginase, however, catalyzes the conversion of L-asparagine to aspartic acid and ammonia. This deprives the leukemic cell of circulating asparagine, which leads to cell death.[11]

Enzyme regulation

This protein may use the morpheein model of allosteric regulation.[12]

History

The discovery and development of asparaginase as an anti-cancer drug began in 1953, when scientists first observed that lymphomas in rat and mice regressed after treatment with guinea pig serum.[13] Later it was found out that it is not the serum itself which provoke the tumour regression, but rather the enzyme asparaginase.[14]

After researches comparing different kinds of asparaginases, the one derived from Escherichia coli and Erwinia chrysanthemi turned out to have the best anti-cancer ability. E. coli has thereby become the main source of asparaginase due to the factor that it is also easy to produce in large amount.[3] Asparaginase produced by Erwinia chrysanthemi instead is known as crisantaspase (BAN), and is available in the United Kingdom under the trade name Erwinase.[5]

References

- ↑ H. Geckil; S. Gencer. (2004). "Production of L-asparaginase in Enterobacter aerogenes expressing Vitreoscilla hemoglobin for efficient oxygen uptake.". Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 63 (6): 691–97. doi:10.1007/s00253-003-1482-5. PMID 14593509.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Müller, H. (1998). "Use of L-asparaginase in childhood ALL". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 28 (2): 97–11. doi:10.1016/S1040-8428(98)00015-8.

- ↑ https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/32147

- 1 2 3 4 "8.1.5: Other antineoplastic drugs". British National Formulary (BNF 57). United Kingdom: BMJ Group and RPS Publishing. March 2009. p. 476. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

- ↑ Appel IM, van Kessel-Bakvis C, Stigter R, Pieters R (2007). "Influence of two different regimens of concomitant treatment with asparaginase and dexamethason] on hemostasis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Leukemia. 21 (11): 2377–80. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2404793. PMID 17554375.

- 1 2 Kornbrust, B.A., Stringer, M.A., Lange, N.K. and Hendriksen, H.V. (2010) Asparaginase – an enzyme for acrylamide reduction in food products. In: Enzymes in Food Technology, 2nd Edition. (eds Robert J. Whitehurst and Maarten Van Oort). Wiley-Blackwell, UK, pp. 59-87.

- ↑ Johnston, P. G.; Hardisty, R. M.; Kay, H. E.; Smith, P. G. (1974). "Myelosuppressive effect of colaspase (L-asparaginase) in initial treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia". British Medical Journal. 3 (5923): 81–83. doi:10.1136/bmj.3.5923.81. PMC 1611087

. PMID 4604804.

. PMID 4604804. - ↑ Hendriksen, H.V.; Kornbrust, B.A.; Oestergaard, P.R.; Stringer, M.A. (April 23, 2009). "Evaluating the Potential for Enzymatic Acrylamide Mitigation in a Range of Food Products Using an Asparaginase from Aspergillus oryzae". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (10): 4168–4176. doi:10.1021/jf900174q. PMID 19388639. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ↑ Fernandes, H. S.; Teixeira, C. S. Silva; Fernandes, P. A.; Ramos, M. J.; Cerqueira, N. M. F. S. A. (4 November 2016). "Amino acid deprivation using enzymes as a targeted therapy for cancer and viral infections". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 0 (ja): null. doi:10.1080/13543776.2017.1254194. ISSN 1354-3776.

- ↑ Broome, J. D. (1981). "L-Asparaginase: Discovery and development as a tumor-inhibitory agent". Cancer treatment reports. 65 Suppl 4: 111–114. PMID 7049374.

- ↑ T. Selwood; E. K. Jaffe. (2011). "Dynamic dissociating homo-oligomers and the control of protein function.". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 519 (2): 131–43. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.020. PMC 3298769

. PMID 22182754.

. PMID 22182754. - ↑ Kidd, J. G. (1953). "Regression of transplanted lymphomas induced in vivo by means of normal guinea pig serum. I. Course of transplanted cancers of various kinds in mice and rats given guinea pig serum, horse serum, or rabbit serum". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 98 (6): 565–582. doi:10.1084/jem.98.6.565. PMC 2136344

. PMID 13109110.

. PMID 13109110. - ↑ Broome, J. D. (1963). "Evidence that the L-asparaginase of guinea pig serum is responsible for its antilymphoma effects. I. Properties of the L-asparaginase of guinea pig serum in relation to those of the antilymphoma substance". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 118 (1): 99–120. doi:10.1084/jem.118.1.99. PMC 2137570

. PMID 14015821.

. PMID 14015821.

External links

- Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource motif class CLV_TASPASE1

- Asparaginase at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Crisantaspase information from Macmillan Cancer Support

- U.S. NLM, NIH Drug Information Portal - Asparaginase