Blue Ridge Mountains

| Blue Ridge Mountains | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Mount Mitchell |

| Elevation | 6,684 ft (2,037 m) |

| Coordinates | 35°45′53″N 82°15′55″W / 35.76472°N 82.26528°WCoordinates: 35°45′53″N 82°15′55″W / 35.76472°N 82.26528°W |

| Geography | |

Appalachian Mountains | |

| Country | United States |

| States | |

| Parent range | Appalachian Mountains |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Grenville orogeny |

| Type of rock | granite, gneiss and limestone |

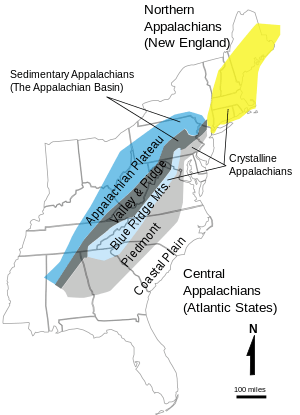

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. This province consists of northern and southern physiographic regions, which divide near the Roanoke River gap.[1] The mountain range is located in the eastern United States, starting at its southernmost portion in Georgia, then ending northward in Pennsylvania. To the west of the Blue Ridge, between it and the bulk of the Appalachians, lies the Great Appalachian Valley, bordered on the west by the Ridge and Valley province of the Appalachian range.

The Blue Ridge Mountains are noted for having a bluish color when seen from a distance. Trees put the "blue" in Blue Ridge, from the isoprene released into the atmosphere,[2] thereby contributing to the characteristic haze on the mountains and their distinctive color.[3]

Within the Blue Ridge province are two major national parks: the Shenandoah National Park, in the northern section, and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, in the southern section. The Blue Ridge also contains the Blue Ridge Parkway, a 469-mile (755 km) long scenic highway that connects the two parks and is located along the ridge crestlines with the Appalachian Trail.[4]

Geography

Although the term "Blue Ridge" is sometimes applied exclusively to the eastern edge or front range of the Appalachian Mountains, the geological definition of the Blue Ridge province extends westward to the Ridge and Valley area, encompassing the Great Smoky Mountains, the Great Balsams, the Roans, the Blacks, the Brushy Mountains (a "spur" of the Blue Ridge) and other mountain ranges.

The Blue Ridge extends as far north into Pennsylvania as South Mountain. While South Mountain dwindles to mere hills between Gettysburg and Harrisburg, the band of ancient rocks that forms the core of the Blue Ridge continues northeast through the New Jersey and Hudson River highlands, eventually reaching The Berkshires of Massachusetts and the Green Mountains of Vermont.

The Blue Ridge contains the highest mountains in eastern North America south of Baffin Island. About 125 peaks exceed 5,000 feet (1,500 m) in elevation.[5] The highest peak in the Blue Ridge (and in the entire Appalachian chain) is Mt. Mitchell in North Carolina at 6,684 feet (2,037 m). There are 39 peaks in North Carolina and Tennessee higher than 6,000 feet (1,800 m); by comparison, only New Hampshire's Mt. Washington rises above 6,000 feet (1,800 m) in the northern portion of the Appalachian chain. Southern Sixers is a term used by peak baggers for this group of mountains.[6]

The Blue Ridge Parkway runs 469 miles (755 km) along crests of the Southern Appalachians and links two national parks: Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains. In many places along the parkway, there are metamorphic rocks (gneiss) with folded bands of light-and dark-colored minerals, which sometimes look like the folds and swirls in a marble cake.

Geology

Most of the rocks that form the Blue Ridge Mountains are ancient granitic charnockites, metamorphosed volcanic formations, and sedimentary limestones. Recent studies completed by Richard Tollo, a professor and geologist at George Washington University, provide greater insight into the petrologic and geochronologic history of the Blue Ridge basement suites. Modern studies have found that the basement geology of the Blue Ridge is made of compositionally unique gneisses and granitoids, including orthopyroxene-bearing charnockites. Analysis of zircon minerals in the granites completed by John Aleinikoff at the U.S. Geological Survey has provided more detailed emplacement ages.

Many of the features found in the Blue Ridge and documented by Tollo and others have confirmed that the rocks exhibit many similar features in other North American Grenville-age terranes. The lack of a calc-alkaline affinity and zircon ages less than 1,200 Ma suggest that the Blue Ridge is distinct from the Adirondacks, Green Mountains, and possibly the New York-New Jersey Highlands. The petrologic and geochronologic data suggest that the Blue Ridge basement is a composite orogenic crust that was emplaced during several episodes from a crustal magma source. Field relationships further illustrate that rocks emplaced prior to 1,078-1,064 Ma preserve deformational features. Those emplaced post-1,064 Ma generally have a massive texture and missed the main episode of Mesoproterozoic compression.[7]

The Blue Ridge Mountains began forming during the Silurian Period over 400 million years ago. Approximately 320 Mya, North America and Europe collided, pushing up the Blue Ridge. At the time of their emergence, the Blue Ridge were among the highest mountains in the world, and reached heights comparable to the much younger Alps. Today, due to weathering and erosion over hundreds of millions of years, the highest peak in the range, Mount Mitchell in North Carolina, is only 6,684 feet high – still the highest peak east of the Rockies.

History

The English who settled colonial Virginia in the early 17th century recorded that the native Powhatan name for the Blue Ridge was Quirank. At the foot of the Blue Ridge, various tribes including the Siouan Manahoacs, the Iroquois, and the Shawnee hunted and fished. A German physician-explorer, John Lederer, first reached the crest of the Blue Ridge in 1669 and again the following year; he also recorded the Virginia Siouan name for the Blue Ridge (Ahkonshuck).

At the Treaty of Albany negotiated by Governor Spotswood with the Iroquois between 1718 and 1722, the Iroquois ceded lands they had conquered south of the Potomac and east of the Blue Ridge to the Virginia Colony. This treaty made the Blue Ridge the new demarcation point between the areas and tribes subject to the Six Nations, and those tributary to the Colony. When colonists began to disregard this by crossing the Blue Ridge and settling in the Shenandoah Valley in the 1730s, the Iroquois began to object, finally selling their rights to the Valley, on the west side of the Blue Ridge, at the Treaty of Lancaster in 1744.

During the Gettysburg Campaign of the American Civil War, the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee commanding, slipped across the Potomac to begin the second invasion of the North. They moved slowly across the Blue Ridge, using the mountains to screen their movements.

Flora and fauna

The forest environment provides natural habitat for many plants, trees, and animals.

Flora

The Blue Ridge Mountains have stunted oak and oak-hickory forest habitats, which comprise most of the Appalachian slope forests. Flora also includes grass, shrubs, hemlock and mixed-oak pine forests.[8]

While the Blue Ridge range includes the highest summits in the eastern United States, the climate is nevertheless too warm to support an alpine zone, and thus the range lacks the tree line found at lower elevations in the northern half of the Appalachian range. The highest parts of the Blue Ridge are generally vegetated in dense Southern Appalachian spruce-fir forests.

Fauna

The area is host to many animals, including:[8]

- Many species of amphibians and reptiles

- A large diversity of fish species, many of which are endemic

- American black bear

- Songbirds and other bird species

- Coyote

- Grouse

- Whitetail deer

- Wild boar

- Wild turkey

In music

- The Grateful Dead song "I've Been All Around This World" contains the lyrics "Up on the Blue Ridge Mountains, there I'll take my stand."

- A particularly well known song about the Blue Ridge is "My Home's Across the Blue Ridge Mountains", first recorded by the Carolina Tar Heels (1929), later by the Carter Family (1937), and still later by others, including Doc Watson and Joan Baez.

- The John Denver hit "Take Me Home, Country Roads" (1971), mentions them in the line "Blue Ridge Mountains, Shenandoah River",[9] a song about West Virginia. (These geographic features only traverse a tiny portion of the easternmost tip of the state, but the song was written in the Blue Ridge Mountains outside of the state according to its authors.[10])

- The song "Battle Born" by The Killers contains the line "From the Blue Ridge to the Black Hills".

- The bluegrass song "Blue Ridge Cabin Home" performed and recorded by many, including Flatt and Scruggs.

- The song "Honeysuckle Blue" by Drivin' 'N' Cryin' contains the line, "Have you ever seen the Blue Ridge Mountains, boy?"

- John Fogerty's first solo album, titled The Blue Ridge Rangers (1973), contains a cover of "Blue Ridge Mountains Blues".

- The song "Stonewall Jackson's Way"[11]

- The song "Blue Ridge Mountain Sky" by The Marshall Tucker Band

- The song "I Was" by Neal McCoy (Written by Phil Vassar)

- The song "Blue Ridge" by Annuals

- The song "Blue Ridge Mountain Blues" by Earl Scruggs

- The symphonic band pieces "Blue Ridge Saga" by James Swearingen and "Blue Ridge Impressions" by Brian Balmages

- Song and album "My Blue Ridge Mountain Boy" (1969) by Dolly Parton

- Country-folk singer Townes van Zandt sang "My home is in the Blue Ridge Mountains" in the song "Blue Ridge Mountains"

- The song "The Trail of the Lonesome Pine"

- The song "Blue Ridge Laughing" by Carbon Leaf

- The song "Blue Ridge Mountains" by Fleet Foxes

- The concert band work "Blue Ridge Saga" by James Swearingen

- The Clemson University alma mater[12] opens with the line "Where the Blue Ridge yawns its greatness...", in reference to the school's location at foot of the mountains

- The song "Levi" from Old Crow Medicine Show's album Carry Me Back (2012), about First Lt.,[13] opens with the lines "Born up on the Blue Ridge/At the Carolina line/Baptized on the banks of the New River".

- Old Crow Medicine Show also mentioned their "Blue Ridge Mountain home" in the lyrics of their song "Half Mile Down", which appeared on their album Carry Me Back (2012).

- The "Blue Ridge Mountain Song" by Alan Jackson

- The concert band work "Blue Ridge Reel" by Brian Balmages

- The Hurray for the Riff Raff song "Blue Ridge Mountain" is the first track on their 2014 album "Small Town Heroes."

- In the song "Old Dominion" by the band Eddie From Ohio, the last line of the first stanza states, "The hills of Coors are nothing more than Blue Ridge wannabes"

- The song "Across the Blue Ridge Mountains" by Rising Appalachia

See also

- Appalachian-Blue Ridge forests

- Appalachian temperate rainforest

- Appalachian balds

- Appalachian bogs

- Cove (Appalachian Mountains)

References

- ↑ "Physiographic divisions of the conterminous U. S.". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ↑ Johnson, A. W (1998). Invitation To Organic Chemistry. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-7637-0432-2.

- ↑ "Blue Ridge Parkway, Frequently Asked Questions". National Park Service. 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ↑ Leighty, Dr. Robert D. (2001). "Blue Ridge Physiographic Province". Contract Report. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DOD) Information Sciences Office. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ↑ Medina, M.A.; J.C. Reid; R.H. Carpenter (2004). "Physiography of North Carolina" (PDF). North Carolina Geological Survey, Division of Land Resources. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ↑ South Beyond 6000

- ↑ Tollo, Richard P.; Aleinkoff, John N.; Borduas, Elizabeth A. (2004). "Petrology and Geochronology of Grenville-Age Magmatism, Blue Ridge Province, Northern Virginia". Northeastern Section (39th Annual) and Southeastern Section (53rd Annual) Joint Meeting. Geological Society of America.

- 1 2 "Blue Ridge Mountains". The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ John Denver. "Take Me Home, Country Roads Lyrics". Lyricsfreak.com. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ↑ "Bill & John Denver". Billdanoff.com. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ↑ "Stonewall Jackson's Way". Poetry and Music of the War Between the States. Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ↑ "Alma Mater". Clemson.edu.

- ↑ "Levi Barnard". NPR.

- Olson, Ted (1998). Blue Ridge Folklife, University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-023-0.

External links

Blue Ridge Mountains travel guide from Wikivoyage

Blue Ridge Mountains travel guide from Wikivoyage