Brotizolam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lendormin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | N05CD09 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 48–95% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Biological half-life | 4.4 hours (range, 2.6–6.9 h) |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

57801-81-7 |

| PubChem (CID) | 2451 |

| DrugBank |

DB09017 |

| ChemSpider |

2357 |

| UNII |

5XZM1R3DKF |

| KEGG |

D01744 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL32479 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.055.404 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

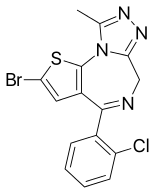

| Formula | C15H10BrClN4S |

| Molar mass | 393.7 g/mol |

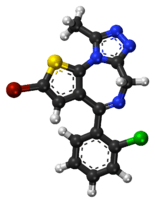

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Brotizolam[2] (marketed under brand name Lendormin) is a sedative-hypnotic[3] thienotriazolodiazepine[4] drug which is a benzodiazepine analog.[5] It possesses anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, hypnotic, sedative and skeletal muscle relaxant properties, and is considered to be similar in effect to short-acting benzodiazepines such as triazolam.[6] It is used in the short-term treatment of severe or debilitating insomnia. Brotizolam is an extremely potent drug and has shown anti-anxiety activity at doses as low as 0.08 to 0.1 milligrams, but the usual hypnotic dose of brotizolam is 0.125 to 0.25 milligrams,[7] and it is rapidly eliminated with an average half-life of 4.4 hours (range 3.6–7.9 hours).[7]

The drug was developed by a team led by T Nishiyama while working for Takeda Chemical Industries in 1976 in Japan.[8]

Brotizolam is not approved for sale in the UK, United States or Canada. It is approved for sale in the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, Portugal, Israel, Italy, Taiwan and Japan.

Indications

Insomnia. Brotizolam is prescribed for the short-term treatment, 2–4 weeks only of severe or debilitating insomnia. Insomnia can be described as a difficulty falling asleep, frequent awakening, early awakenings or a combination of each. Brotizolam is a short-acting benzodiazepine and is sometimes used in patients who have difficulty in maintaining sleep or getting to sleep. Hypnotics should only be used on a short-term basis or in those with chronic insomnia on an occasional basis.[9]

Premedication. Brotizolam, in a dose of 0.25 mg can be used as a premedication prior to surgery, this dose was found to be comparable in efficacy to 2 mg flunitrazepam as a premedicant prior to surgery.[10]

Side effects

Common side effects of brotizolam are typical of hypnotic benzodiazepines and are related to CNS depression, and include somnolence, ataxia, headache, anterograde amnesia, dizziness, fatigue, impairment of motor functions, slurred speech, confusion, and clumsiness.

Less common side effects include hypotension, respiratory depression, hallucinations, nausea and vomiting, palpitations, and paradoxical reactions (i.e. aggression, anxiety, violent behavior, etc.).

Brotizolam can cause residual side effects the next day such as impaired cognitive and motor functions as well as drowsiness. Disruption of sleep patterns may also occur such as suppression of REM sleep. These side effects are more likely at higher doses (above 0.5–1 mg).[11]

In clinical trials brotizolam 0.125 to 0.5 mg improved sleep in insomniacs similarly to nitrazepam 2.5 and 5 mg, flunitrazepam 2 mg and triazolam 0.25 mg, whilst brotizolam 0.5 mg was shown to be superior to flurazepam 30 mg, but inferior to temazepam 30 mg in some studies. Brotizolam at dosages below 0.5 mg at night usually produced minimal morning drowsiness; no residual impairment of psychomotor performance occurs following dosages within the recommended range of 0.125 to 0.25 mg. No serious side effects have been reported to date and the most frequently observed adverse experiences are drowsiness, headache and dizziness. Mild rebound insomnia may occur in some patients when treatment is stopped.[7]

Contraindications and special caution

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in the elderly, during pregnancy, in children, alcohol or drug-dependent individuals and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[12]

Pharmacology

Brotizolam has been shown in animal studies to be a very high potency benzodiazepine, and it may be the most potent benzodiazepine used on humans. Although further studies need to be done to confirm this.[13] The elimination half-life of brotizolam is 3–6 hours. It is absorbed rapidly after administration; after administration it is metabolised into active metabolites, one of which is far less potent than brotizolam and the other is only present in very small amounts in the blood and thus the metabolites of brotizolam do not have any pharmacological effect in humans.[5] Brotizolam induces impairment of motor function and has hypnotic properties.[14]

Brotizolam increases the slow wave light sleep (SWLS) in a dose-dependent manner whilst suppressing deep sleep stages. Less time is spent in stages 3 and 4 which are the deep sleep stages when benzodiazepines such as brotizolam are used. Benzodiazepines are therefore not good hypnotics in the treatment of insomnia. The suppression of deep sleep stages by benzodiazepines may be especially problematic to the elderly as they naturally spend less time in the deep sleep stage.[15]

Abuse

Brotizolam is a drug with a potential for abuse. Drug misuse is defined as taking the drug to achieve a 'high', or continuing to take the drug in the long term against medical advice.[16]

Abuse of brotizolam, although not widespread, was a problem in Hong Kong back in the late 1980s and 1990s. To control benzodiazepine abuse in Hong Kong, the Government's Pharmacy and Poisons Board reclassified benzodiazepines as Dangerous Drugs in October 1990. Apart from formal prescriptions, detailed records were then required for the supply and dispensing of these drugs. These regulations were applied initially only to brotizolam, triazolam and flunitrazepam as they were the major benzodiazepines of abuse. The impact of these regulatory changes on benzodiazepine use has been studied by analyzing the sales patterns of seven benzodiazepines between 1990–1993. In 1991, the sales of flunitrazepam and triazolam fell, but the sales of five unrestricted benzodiazepines increased.[17] Particular problems arose with the trafficking and abuse of nimetazepam and the abuse of temazepam within that same year in 1991. The regulations that were originally only applied to brotizolam, triazolam and flunitrazepam were now being extended to include all benzodiazepines by January 1992. A regulation requiring the use of proper prescriptions and detailed records for the supply and dispensing of benzodiazepines, appears to have curbed, at least partially, their abuse in Hong Kong. There is still some problems with temazepam, nimetazepam, triazolam, and brotizolam but it is not major.

Commercial names

| Name |

Countries |

| Bondormin, Brotizolam |

Israel |

| Dormex |

Chile |

| Lendorm |

Austria, Denmark |

| Lendormin |

South Africa, Belgium, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Portugal, Taiwan |

| Lendormine |

Switzerland |

| Lindormin |

Mexico |

| Noctilan |

Chile |

| Sintonal |

Spain |

See also

- Benzodiazepines

- Benzodiazepine dependence

- Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome

- Long-term effects of benzodiazepines

- Midazolam

- Triazolam

- Loprazolam

Notes

- ↑ http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/orangebook/e_cs_sched.pdf

- ↑ DE Patent 2445430

- ↑ Fink, Max; Irwin, Peter (1981). "Pharmacoelectroencephalographic study of brotizolam, a novel hypnotic". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 30 (3): 336–42. doi:10.1038/clpt.1981.169. PMID 7273596.

- ↑ Catabay, A.; Taniguchi, M.; Jinno, K.; Pesek, J. J.; Williamsen, E. (1 March 1998). "Separation of 1,4-Benzodiazepines and Analogues Using Cholesteryl-10-Undecenoate Bonded Phase in Microcolumn Liquid Chromatography". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 36 (3): 113. doi:10.1093/chromsci/36.3.111.

- 1 2 Jochemsen, R; Wesselman, JG; Van Boxtel, CJ; Hermans, J; Breimer, DD (1983). "Comparative pharmacokinetics of brotizolam and triazolam in healthy subjects". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 16 (Suppl 2): 291S–297S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb02303.x. PMC 1428224

. PMID 6140948.

. PMID 6140948. - ↑ Mandrioli, Roberto; Mercolini, Laura; Raggi, Maria A. (2008). "Benzodiazepine Metabolism: an Analytical Perspective". Current Drug Metabolism. 9 (8): 827–44. doi:10.2174/138920008786049258. PMID 18855614.

- 1 2 3 Langley, MS; Clissold, SP (1988). "Brotizolam. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy as a hypnotic". Drugs. 35 (2): 104–22. doi:10.2165/00003495-198835020-00002. PMID 3281819.

- ↑ US patent 4017620, Yutaka Kuwada et al, "Thienodiazepine derivatives", published 1975-08-05, issued 1977-12-04

- ↑ Rickels, K. (1986). "The clinical use of hypnotics: indications for use and the need for a variety of hypnotics". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 74: 132–41. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb08990.x. PMID 2883820.

- ↑ Nishiyama, Tomoki; Yamashita, Koichi; Yokoyama, Takeshi; Imoto, Akinobu; Manabe, Masanobu (2007). "Effects of quazepam as a preoperative night hypnotic: comparison with brotizolam". Journal of Anesthesia. 21 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1007/s00540-006-0445-2. PMID 17285406.

- ↑ Nicholson, AN; Stone, BM; Pascoe, PA (1980). "Studies on sleep and performance with a triazolo-1, 4-thienodiazepine (brotizolam)". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb00504.x. PMC 1430017

. PMID 7397057.

. PMID 7397057. - ↑ Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, A.A.; Vennat, B.; Llorca, P.-M.; Eschalier, A. (2009). "Dépendance aux benzodiazépines : le syndrome de sevrage" [Benzodiazepine dependence: Focus on withdrawal syndrome]. Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises (in French). 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- ↑ Shibuya, Takeshi; Field, Richard; Watanabe, Yasuo; Sato, Katsuhiko; Salafsky, Bernard (1984). "Structure-affinity relationships between several new benzodiazepine derivatives and 3H-diazepam receptor sites". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 34 (4): 435–40. doi:10.1254/jjp.34.435. PMID 6144807.

- ↑ Yasui, M; Kato, A; Kanemasa, T; Murata, S; Nishitomi, K; Koike, K; Tai, N; Shinohara, S; Tokomura, M (2005). "Pharmacological profiles of benzodiazepinergic hypnotics and correlations with receptor subtypes". Nihon shinkei seishin yakurigaku zasshi. 25 (3): 143–51. PMID 16045197.

- ↑ Noguchi, Hideaki; Kitazumi, Kazuhiro; Mori, Megumi; Shiba, Toshiharu (2004). "Electroencephalographic Properties of Zaleplon, a Non-Benzodiazepine Sedative/Hypnotic, in Rats". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 94 (3): 246–51. doi:10.1254/jphs.94.246. PMID 15037809.

- ↑ Griffiths, RR; Johnson, MW (2005). "Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 (Suppl 9): 31–41. PMID 16336040.

- ↑ Lee, KK; Chan, TY; Chan, AW; Lau, GS; Critchley, JA (1995). "Use and abuse of benzodiazepines in Hong Kong 1990-1993--the impact of regulatory changes". Journal of toxicology. Clinical toxicology. 33 (6): 597–602. doi:10.3109/15563659509010615. PMID 8523479.

References

- Greenblatt, DJ; Locniskar, A; Shader, RI (1983). "Pilot pharmacokinetic study of brotizolam, a thienodiazepine hypnotic, using electron-capture gas-liquid chromatography". Sleep. 6 (1): 72–6. PMID 6844800.

- Langley, MS; Clissold, SP (1988). "Brotizolam. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy as an hypnotic". Drugs. 35 (2): 104–22. doi:10.2165/00003495-198835020-00002. PMID 3281819.

- Bechtel, WD (1983). "Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of brotizolam in humans". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 16 (Suppl 2): 279S–283S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb02301.x. PMC 1428235

. PMID 6661373.

. PMID 6661373. - Jochemsen, Roeline; Wesselman, J. G. J.; Hermans, J.; van Boxtel, C. J.; Breimer, D. D. (1983). "Pharmacokinetics of brotizolam in healthy subjects following intravenous and oral administration". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 16 (Suppl 2): 285S–290S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb02302.x. PMC 1428208

. PMID 6661374.

. PMID 6661374.